The material was created within the framework of the project “Do not Believe Myths” with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation.

We all want to receive treatment from a highly qualified, involved doctor, who really wants us to get healthy and never need their services again. But where do you find a specialist like that, where do they come from? There is only one possible answer to this question: first of all, a good doctor in the future is a good medical student in the present.

Of course, a lot depends on the student's motivation, their talent and the ability to learn and analyze. So what should be the instruments which can be used to assess academic performance of a medical student and their future as a doctor? We are referring to the system of exams and tests. They help determine whether today's student will make a good doctor tomorrow.

VoxUkraine analysts tried to learn about the exams we have in Ukraine and, most importantly, the way they affect future qualification of doctors.

Three ‘KROKs’ to a Doctor

The system of assessment at medical schools is an extremely important factor in medical education – both in Ukraine and abroad. Ukrainian medical students have been passing KROK exam since 1998:

- during the third year of studies they pass Krok 1 (fundamental disciplines);

- during the final year of studies they pass Krok 2 (clinical disciplines);

- during internship they pass Krok 3.

The exams have been developed in close international cooperation and are based on the best world practices. It was the first success story of independent assessment development in Ukraine, which was also used when External Independent Assessment was launched in early 2000s.

Yet, despite the use of best world practices, students, teachers and doctors are often critical about Krok exams.

Most complaints concern the quality of tests. In response to criticism, Testing Centre was continuously saying that the tests were prepared by university teachers so they should be the ones to answer questions. In their turn, the teachers, are complaining, and rightfully so, about lack of payment for the complicated task of developing tests. Obviously, not all quality issues have to do with the level of teacher motivation. There are questions about the syllabi that the exam questions are based on and inconsistencies of answers to the same question in different exam tasks. All things considered, it becomes apparent that the existing model of preparation for the test exam cannot guarantee quality result.

Apart from complaints about the quality of tests, students and teachers constantly express doubt as to the level of transparency and objectivity of Krok assessment. They are voicing various sums needed to `deal with this`, giving names of people that can allegedly help and retelling stories of those who allegedly `got everything handled`. At the same time, over the 20 years of Krok existence no one was able to prove any of those suspicions or allegations.

Analysis of KROK Results

In the summer of 2018, Ministry of Healthcare of Ukraine (MoH) asked Testing Centre to provide complete information on Krok exam results. In view of planned changes in the assessment of medical students, MoH wanted to do a more comprehensive analysis of the academic results. Authors of this article got the resulting depersonalized data.

All in all, it includes information about more than 197,000 exams taken between 2009 and 2018 (yet, there are years or exams for which data was not supplied).

One of the key issues that most people pay attention to when analyzing tests is how natural the distribution of points is. ‘Normal (or natural) distribution’ is one of the key concepts in statistics. Back in the 19th century mathematicians noticed that for numerous samples of observations graphic presentation of probability is bell-shaped. Such distribution is called ‘normal’ or ‘Gaussian’ after the mathematician who formulated this key concept of statistics for the first time.

What does this mean for test studies? There is a certain ‘normal distribution’ of the results: a small number of persons receive the lowest points, a slightly higher result goes to a slightly bigger number of people and as the result increases the number of people who get them increases. As it reaches a certain point, the value starts decreasing so a very small number of people gets the highest point.

When analyzing the distribution of Krok results, a few things come to the foreground. A small number of students gets the lowest number of points which corresponds to the number of correct answers. As the number of points increases so does the number of people who get them. Then, however, the number of people who got a certain number of points rapidly drops.

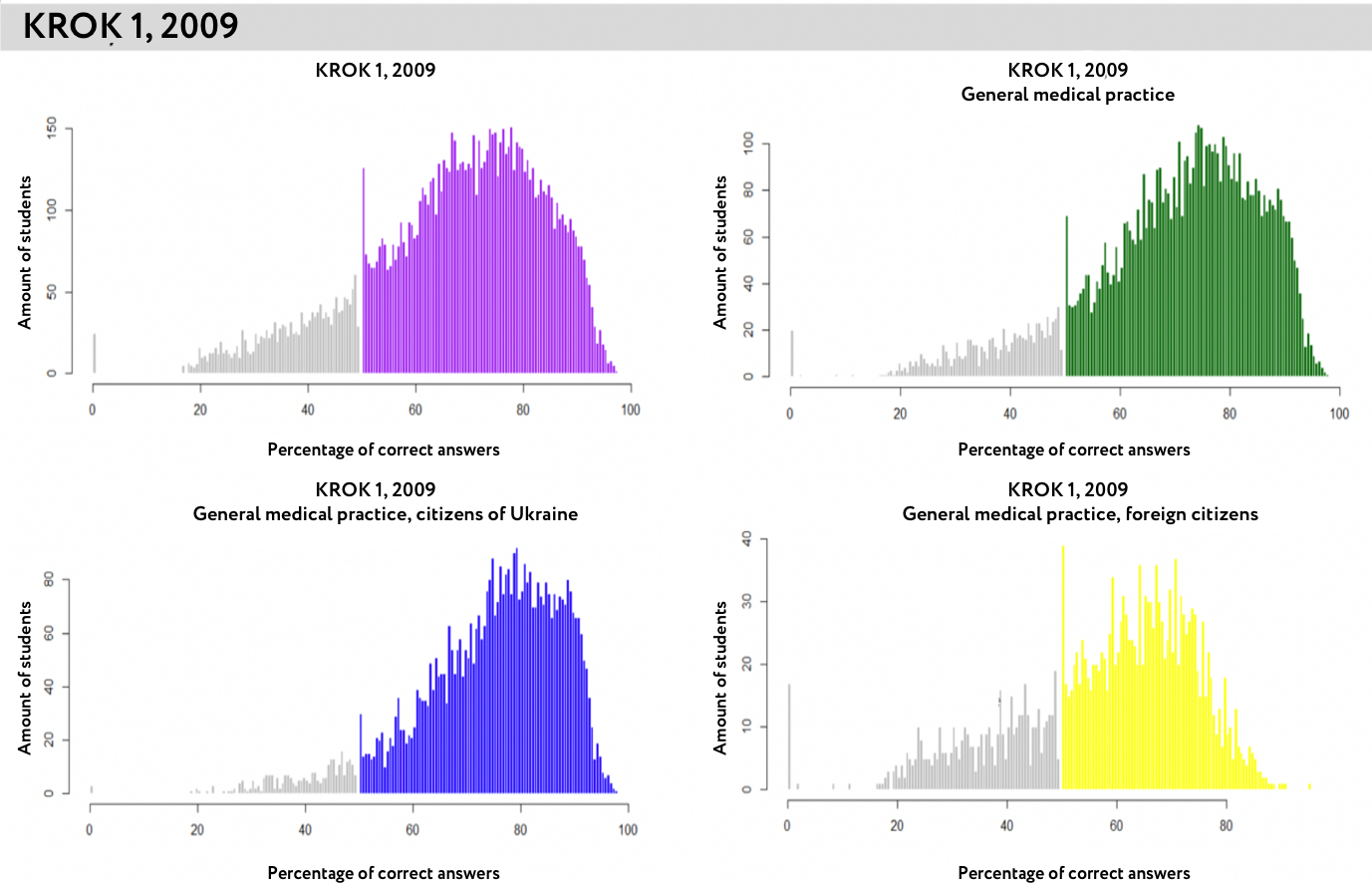

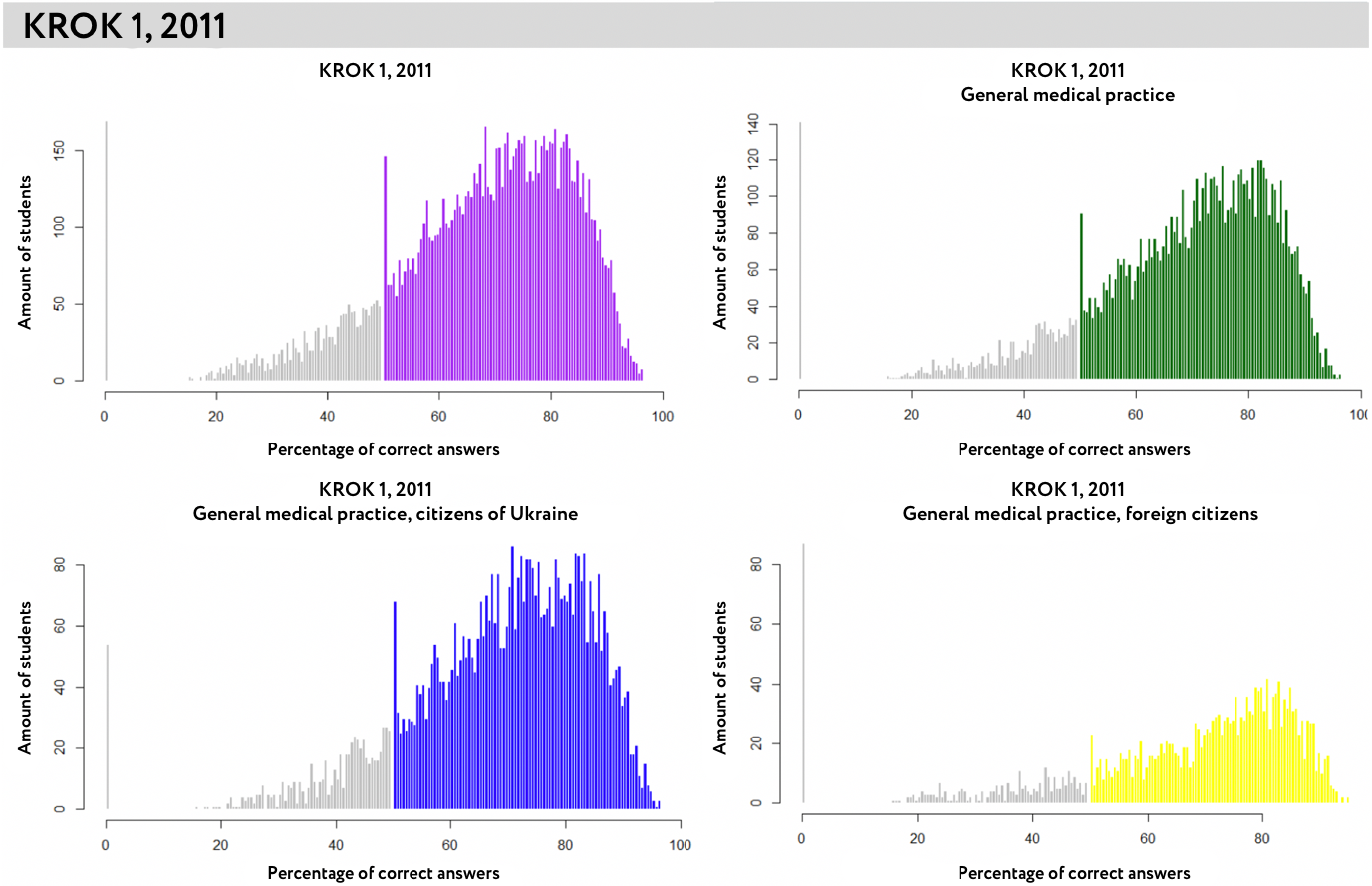

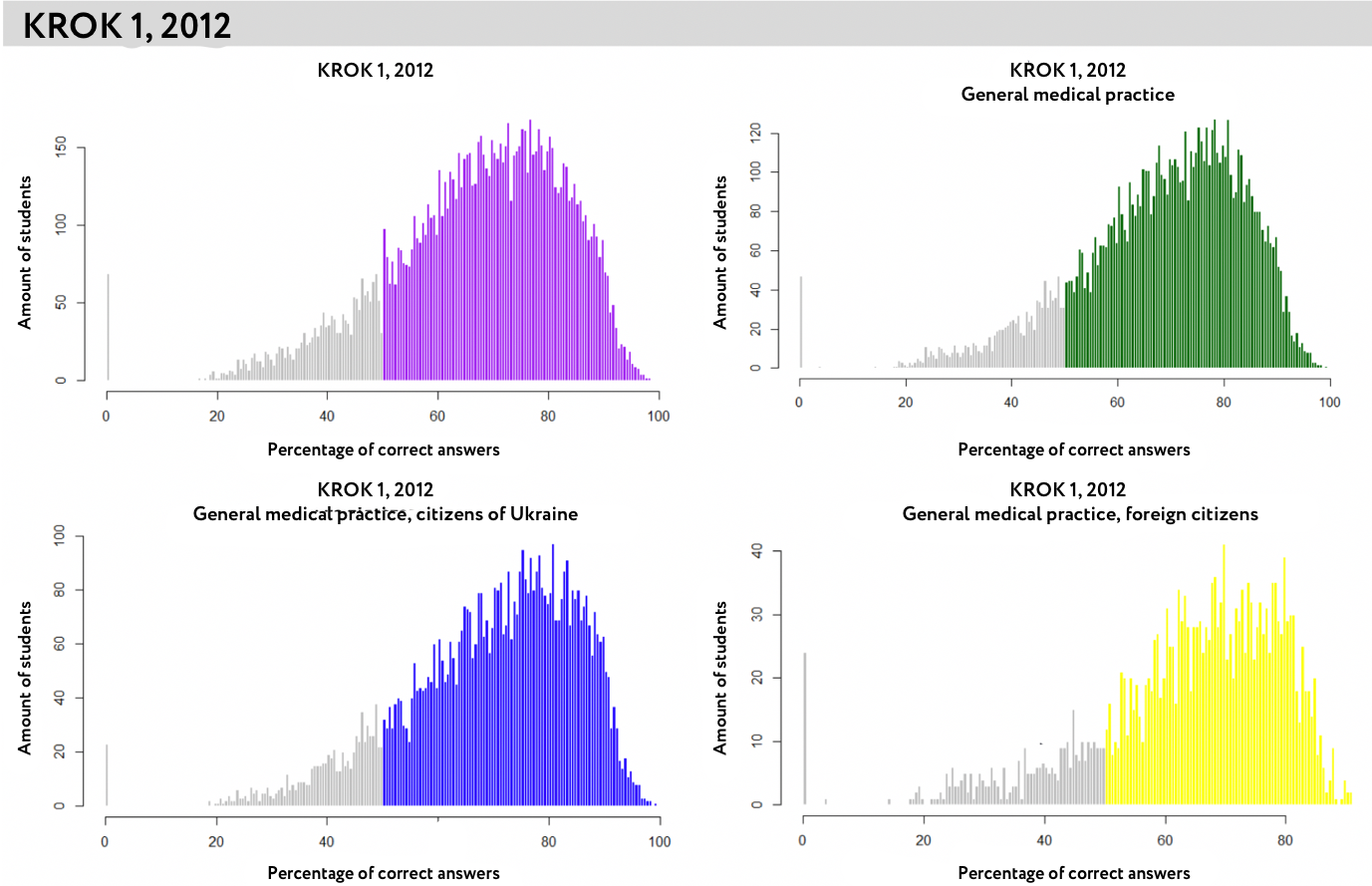

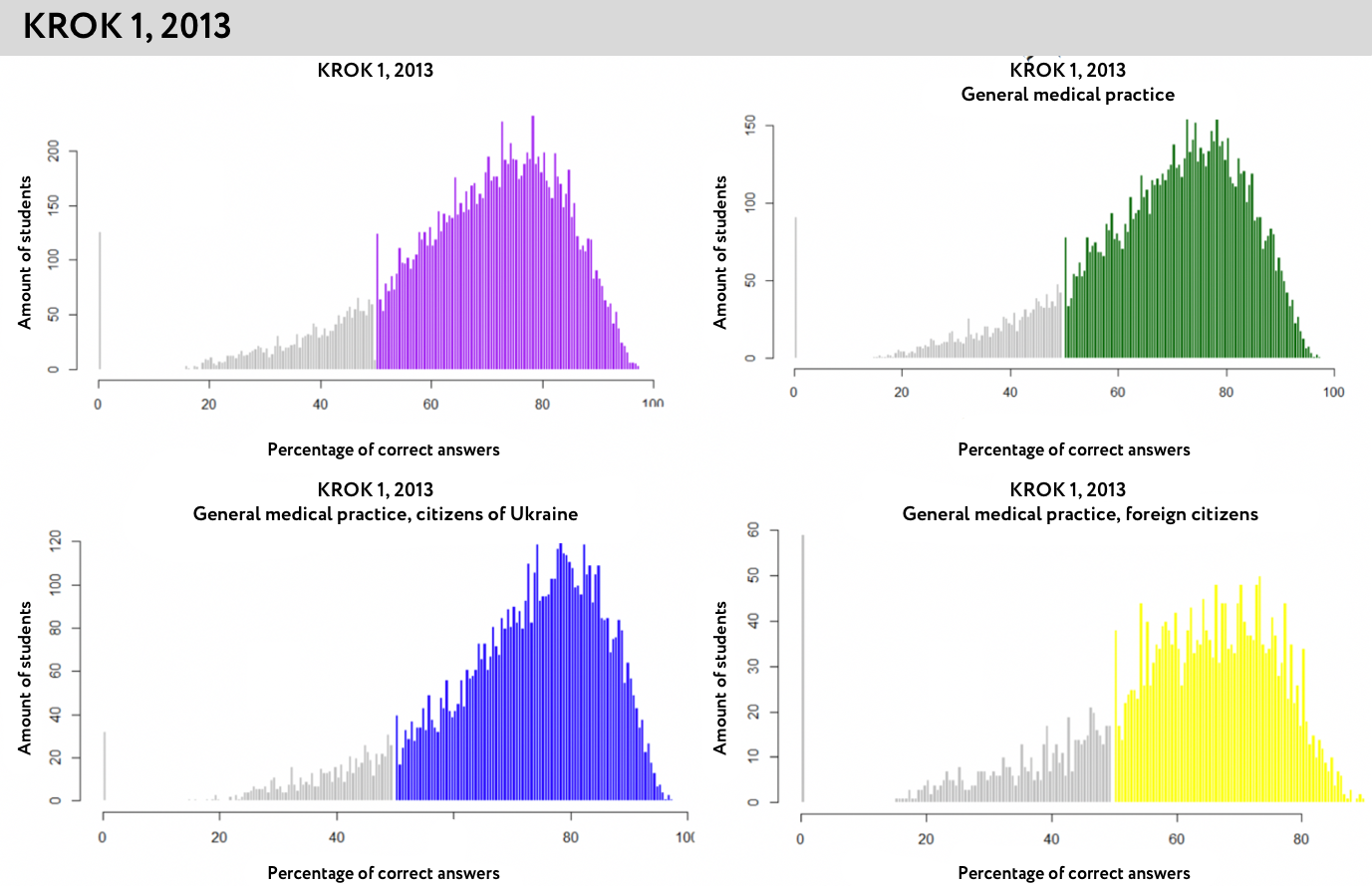

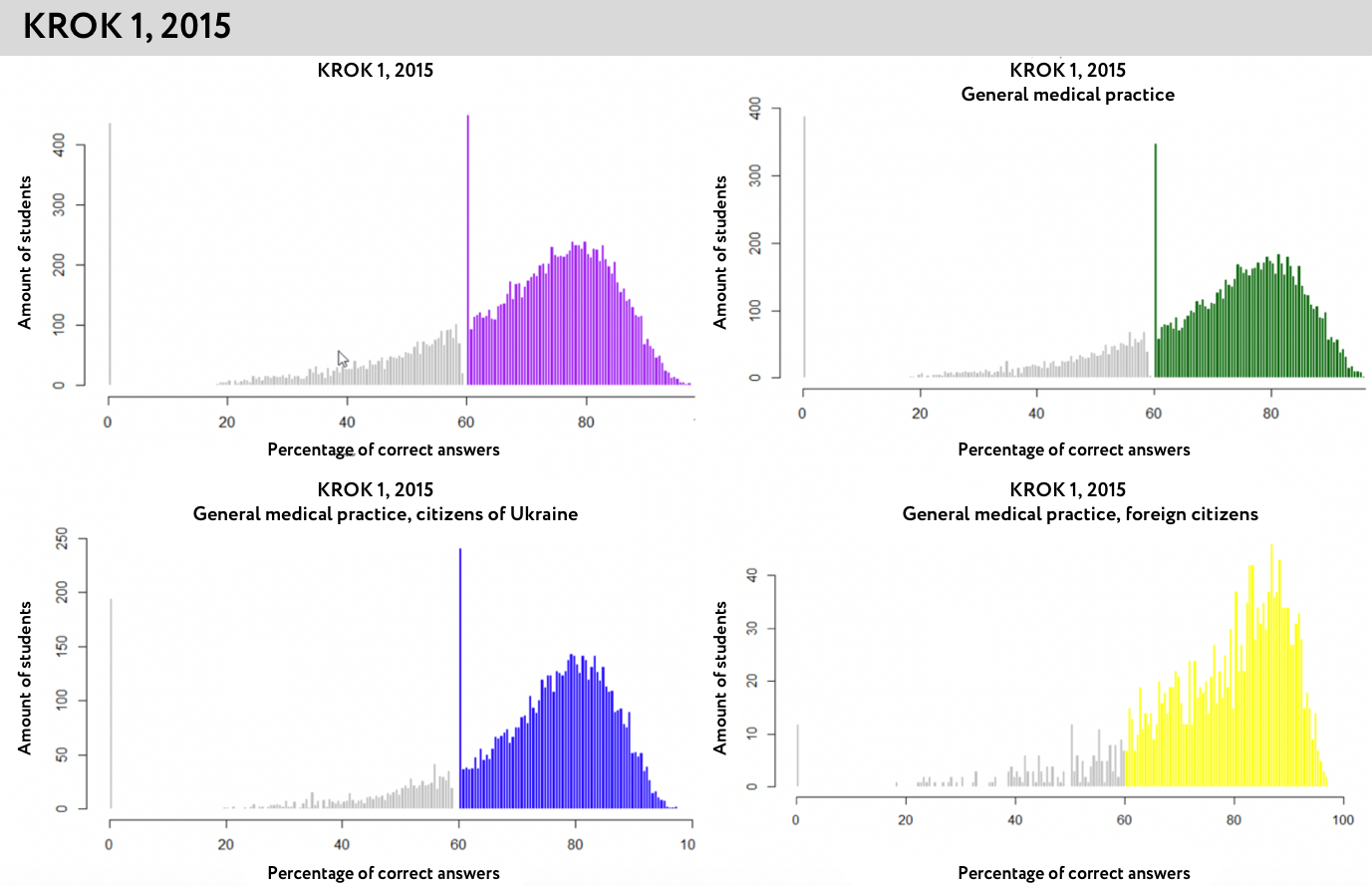

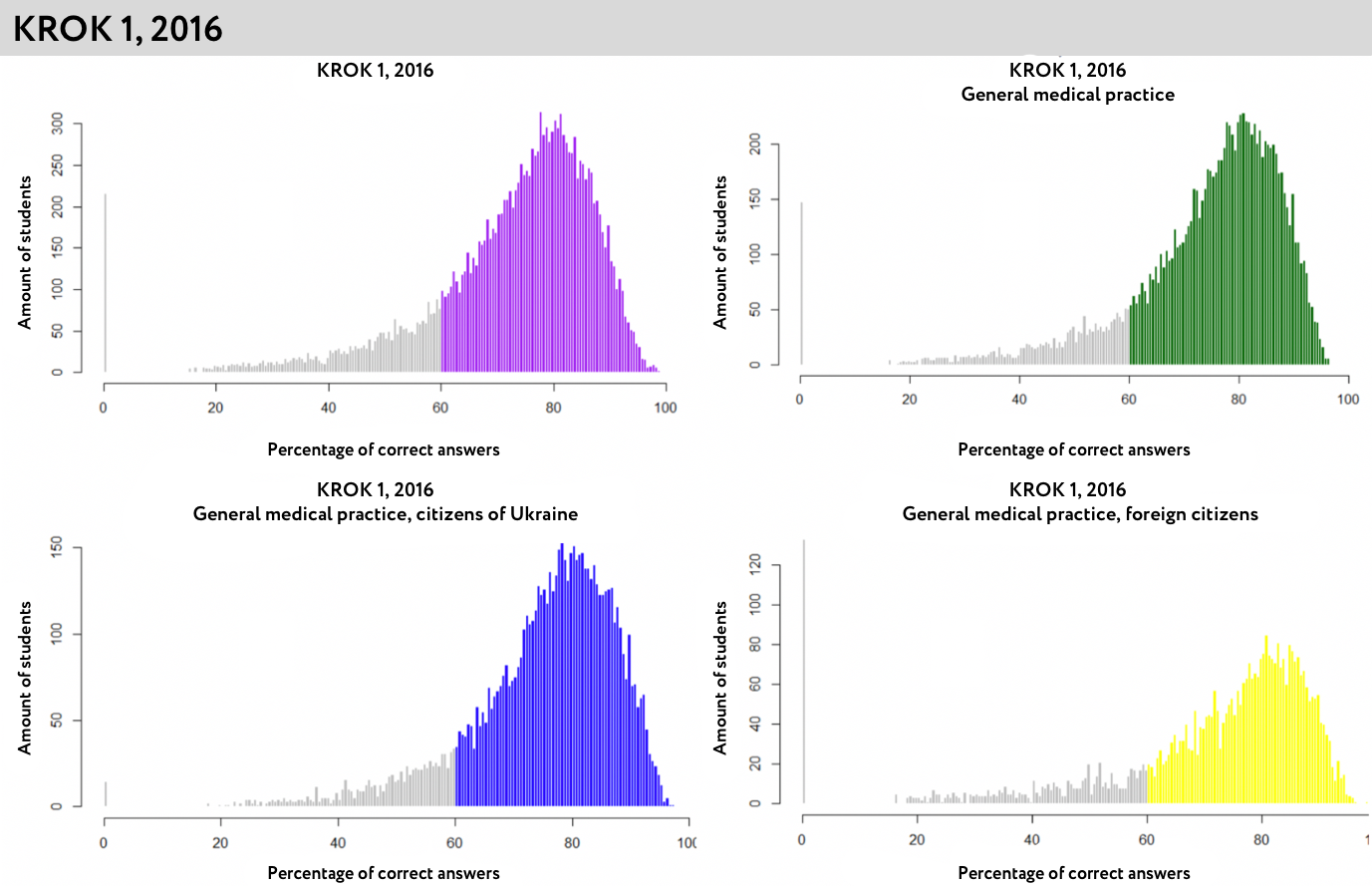

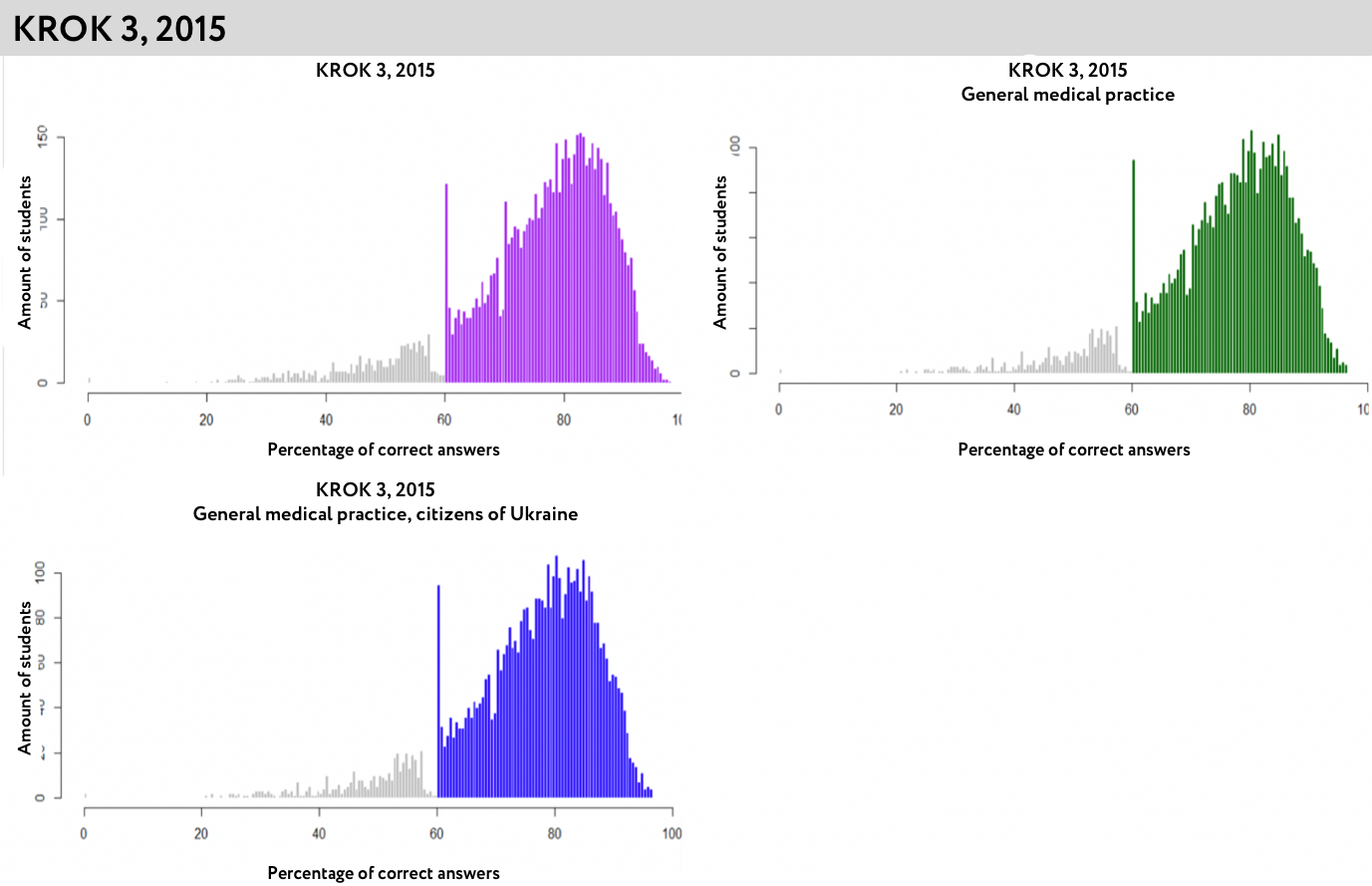

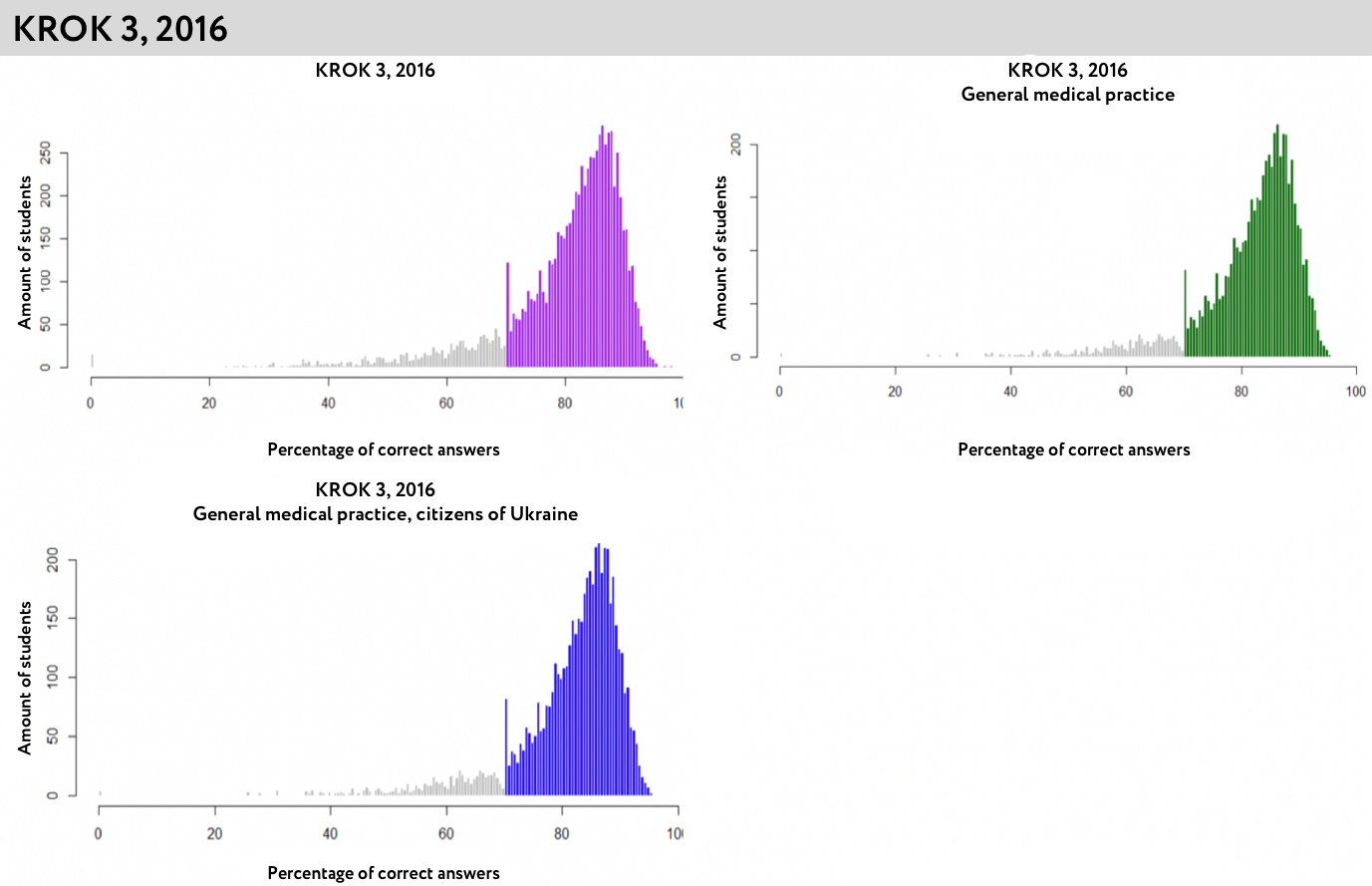

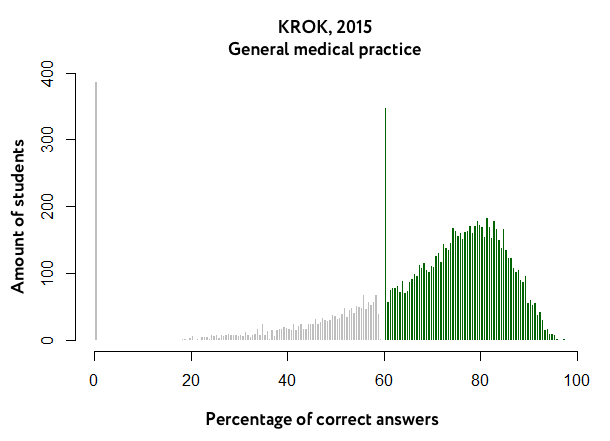

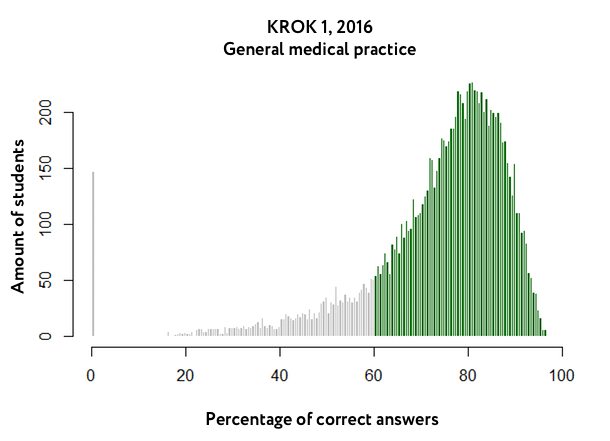

Figures for Krok 1 (Fig. 2) show a `gap` around 50% mark for the years 2009-2014. However, the number of people who got 50.5% in 2009-2014 is disproportionately high – higher than the number of people who got 51%. In 2015 (Fig. 1) the same situation may be observed but for a different part of the curve: 60% - a rapid decrease of the number of people; 60.5% - a high number of people.

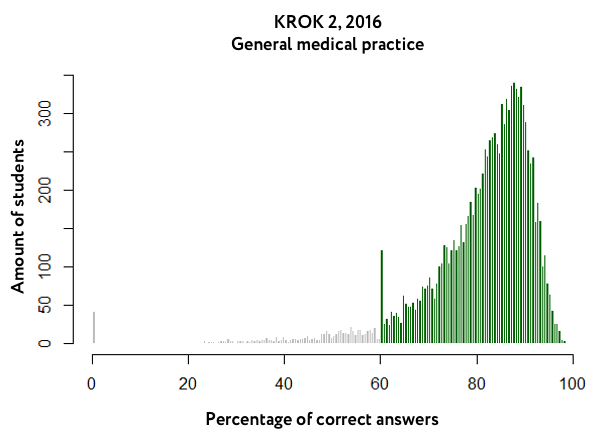

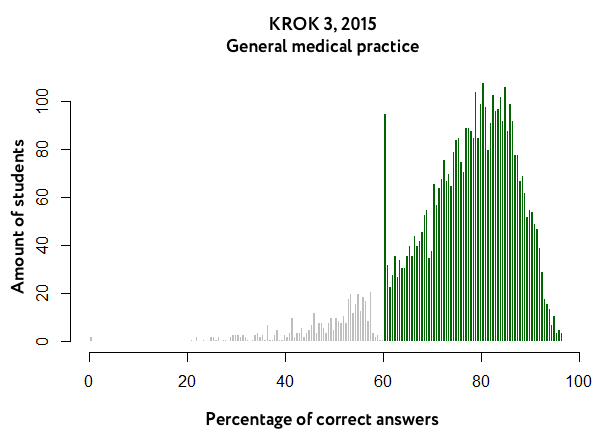

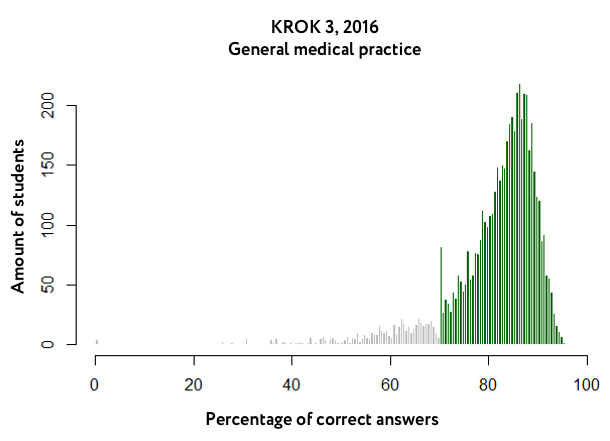

(marked grey are the results below the mark ‘pass/not pass’, violet are the results that are higher than the threshold)

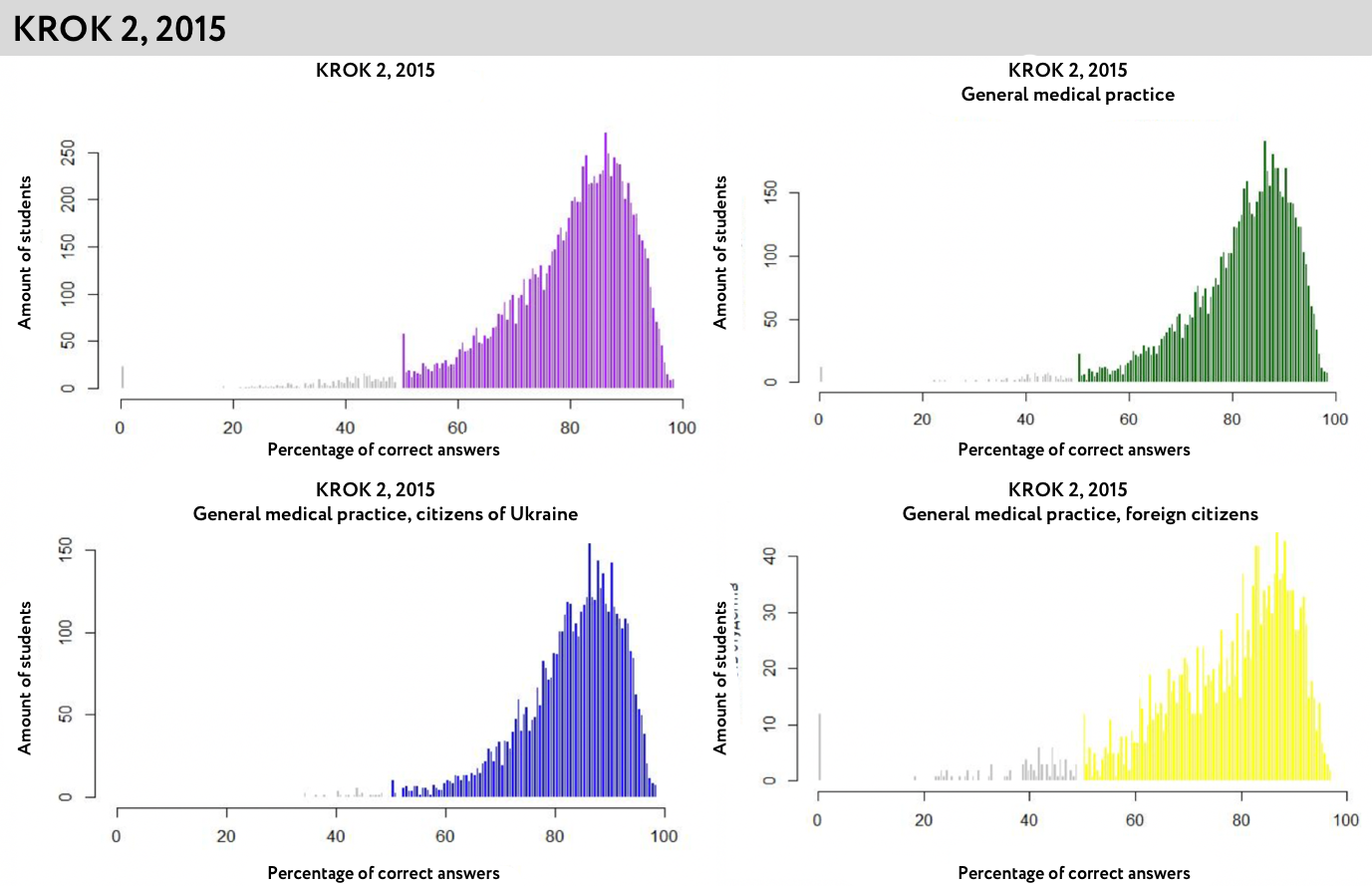

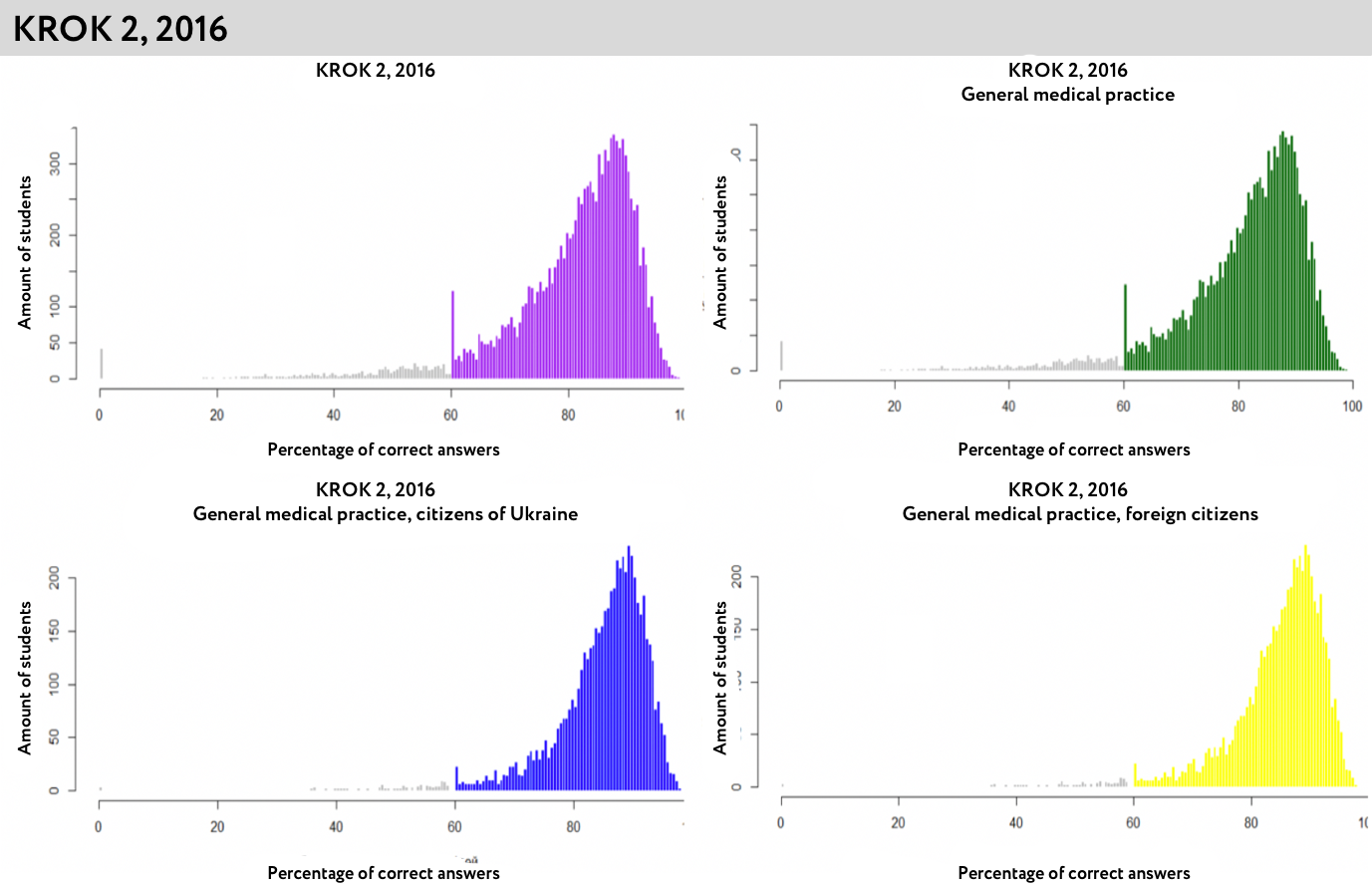

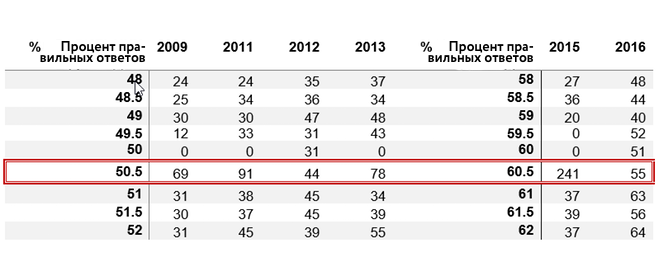

As a matter of fact, we are witnessing a disproportionately higher number of students who got a specific number of points. At the same time, the `abnormal` increase clearly coincides with the `pass/not pass` threshold every time. Thus, in 2015 the `pass/not pass` threshold increased from 50.5% to 60.5% - and the jump reached exactly the same level. A similar situation is seen with Krok 2 and Krok 3.

What we are seeing on the chart is called discontinuity distribution. Scientists have already researched this phenomenon. In particular, such research was conducted to assess the values of regulatory procedures compliance. Research shows that an inexplicably large share of companies find themselves right before the threshold value which signifies implementation of regulations. Researchers have also analyzed such distribution to see how people optimize their taxes. Many people have lower than threshold value income, where the threshold value stands for the next level of tax rate.

What are we seeing here?

What are the trends that we see in analyzed data?

- Data for most years shows a rapid increase of the number of people who got a number of points which coincides with the threshold value of 'pass/not pass'.

- The height of ‘jump’ is different for different years. What we see is that for some years the height of 'jumP' actually compensates for the decrease on the previous value, which proves that the points of persons who got 0.5 less than the threshold value, were 'added up'. At the same time, in some years the rapid jump cannot be explained by the 'add ups only' During some years the jump is 2.5 times higher than the average value between two neighbouring positive values, for other years it is 8 times higher or almost the same. If the add ups were done automatically and the approach was the same in all cases, the deviation would be more or less the same.

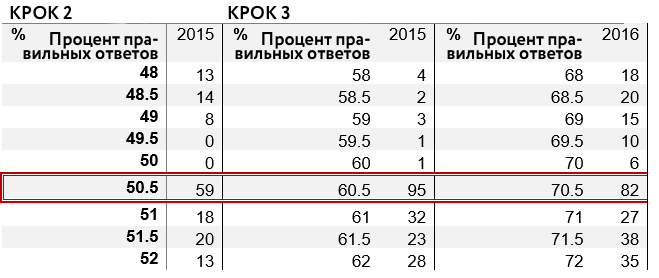

- Charts for different years are different, which shows change in the approach toward assessments. Thus, in some years there were no students who got 0.5% below the threshold value. Theoretically, this may attest to automatic ‘add-up’. At the same time, there are students in other years who got 0.5% under the ‘pass/not pass’ threshold, yet their number is significantly lower than what we could expect from the distribution curve. Krok 1 in 2016 does not even have the ‘jump’ in its distribution. This shows that different approaches were used to determine the final result (Table 1).

Table 1. Share and number of correct answers in Krok 1 exam for various years

Table 2. Share and number of correct answers in Krok 2 and Krok 3 exam for various years

Table 2. Share and number of correct answers in Krok 2 and Krok 3 exam for various years

- Curve for Krok 2 results is significantly shifted toward the higher values, i.e. the school-leaving Krok 2 exam is notably easier than the Krok 1 exam. When comparing Krok 1, Krok 2 and Krok 3 results (Fig. 3) we can see the difference on visual inspection: a lot less students get results in the range between 50 and 75 as compared to the Krok 1 results. Simultaneously, a larger share of students got very high results.

Such a distribution shows that the test is comparatively easier and most students reach the ‘pass/not pass’ threshold easily. In general, Krok 2 results show that a very small share of students get less points than what is required to reach the ‘pass/not pass’ threshold.