The modern media is powerful and influential. At least, according to the US intelligence. The CIA, FBI, and NSA have recently produced a joint report titled Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections. Half of the 14 pages of the report's substantive part contain analysis of activities of the Russia Today (RT) TV channel. Despite criticism of the article, most arguments concerning allegations of the intelligence agencies are built upon the biased information presented in the Russian media, and impact of Russia Today on the public opinion shouldn't be underestimated.

We don't know whether Ukrainian security services study activities and content of Russia Today, but we know that they write and broadcast footages showing the conflict in Ukraine. Based on a specific vocabulary, used by Ukraine Today and Russia Today, we classified articles of the world's leading Internet media into two categories — pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian.

The "Око" project provided VoxUkraine with a sample of 235,000 English articles1, which contain references to Ukraine and were published within the period from January 2014 to October 2016. Articles cover a wide range of topics including sports, culture, politics, and economics. To download the raw data, visit data.voxukraine.org.

It is possible to classify a text as pro- or anti-Ukrainian using a toolkit that is used for sorting through email content to find illicit and legitimate messages. Classification algorithms calculate the probability of the incoming text belonging to one of the classes. For example, Mozilla Thunderbird programme uses filtering of incoming messages based on statistical models.

In this article, the roles of illicit and legitimate messages are played by the openly pro-Ukrainian Ukraine Today (a class of articles with pro-Ukrainian vocabulary) and the anti-Ukrainian Russia Today (a class of articles with pro-Russian vocabulary). Our task is to automatically split the articles into two classes: pro-Ukrainian, whose vocabulary is similar to Ukraine Today, and pro-Russian, lexically similar to Russia Today.

Let's start with the narrative. Articles about Ukraine published on Russia Today are three times less frequent than those published on Ukraine Today (1770 versus 5176). There's a simple explanation: Russia Today features news from around the world, while Ukraine Today writes more about Ukraine and Eastern Europe2. Articles on the Ukrainian website are shorter, the average number of characters is 967. Articles on Russia Today are three times longer and consist of 3241 symbols on average. To understand the reason for such a big difference, we'll analyse the structure of the links to articles.

The link structures on Ukraine Today and Russia Today are similar. First comes the name of the site http://uatoday.tv or https://rt.com, followed by the name of the category — news, politics, or business, and then there's the article title, for example 360925-mh17-crash-jit-report3. When splitting the articles into categories, we can calculate the number of articles in each category and the average number of characters in an article.

| RUSSIA TODAY [1770] | UKRAINE TODAY [5176] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of characters | number of articles | number of characters | number of articles | ||

| News | 2889 | 51% | Politics | 828 | 42% |

| Business | 1702 | 16% | News | 671 | 22% |

| Op-Edge | 5100 | 14% | Society | 1088 | 20% |

| Politics | 3187 | 8% | Business | 969 | 5% |

| US | 3507 | 3% | Other | 1029 | 4% |

| Other | 2915 | 3% | Crime | 932 | 3% |

| Shows | 3868 | 3% | Opinion | 1541 | 2% |

| UK | 3022 | 1% | Geopolitics | 767 | 2% |

More than half of the articles about Ukraine on the RT website are classified as "news". The average length of an article in this category is 2889 characters. The articles in the "Politics", "US", "Show", and "United Kingdom" categories are longer. The "USA" and "United Kingdom" categories include news from those countries that refer to Ukraine. The "Show" category includes documentaries, discussions on the global economy and politics. The shortest texts can be found in the category "Business News" — they consist of 1700 characters on average.

Standing out from the list is the "Op-Edge" section (5100 characters on average) — "is a platform for those unafraid to voice their stance and question what are considered established truths." Simply put, this section includes political commentary, articles by foreign journalists and bloggers, and readers' letters. For example, an active columnist is - Bryan MacDonald, a Moscow-based Irish journalist with a dubious reputation.

Some 40% of the articles on Ukraine Today fall into the "Politics" category. The "News" category contains almost half the articles (consisting of 671 characters on average, they are also the shortest). Standing out against the background is the "Opinion" category, where the average article length is 1541 characters. Columns by journalists, experts, and public figures usually fall into this category.

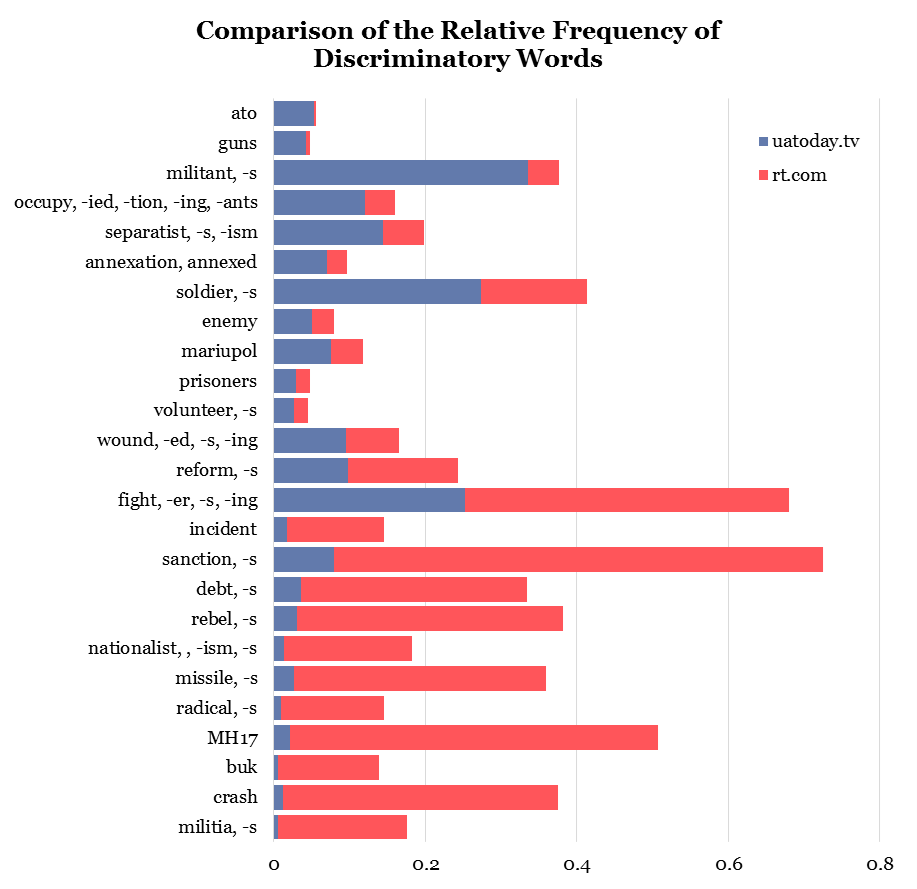

The differences in vocabulary used by Ukrainian and Russian websites is quite noticeable. If we count how many times a word was used in the articles and divide it by the number of articles, we'll find out the relative frequency of this word. By calculating this metric for both resources, we can identify the discriminatory words — the "breakwaters" that help determine to which category the article belongs. For example, if an article contains such words as "separatist", "occupation", or "annexation", it's most likely to belong to the pro-Ukrainian category.

Let have a closer look at the discriminatory words. Ukrainian website often uses the abbreviation "ATO". It is obvious, since Ukraine Today publishes reports from the ATO zone. RT cannot call the Donbass conflict an anti-terror operation, because it doesn't consider people fighting on the side of DNR and LNR terrorists. To describe the belligerents in the east of Ukraine, Ukraine Today more frequently uses such words as "militant", "separatist", and "soldier". Meanwhile, Russia Today is much more likely to use the words "militia" and "rebel". Readers of the Ukrainian website are more likely to come across words "occupation", "annexation", and "enemy", which speak in a negative tone about the aggression of the Russian Federation.

In addition to the military topic, it's worth paying attention to the following discriminatory words: "debt" and "sanctions". Russian media and authorities frequently use sanctions as an excuse for domestic problems. The second hot topic, "Debt talks", arose in the context of Ukraine's gas debt to Russia and the question whether Ukraine will be able to pay off its debts.

Discriminatory words are undoubtedly important — they serve as beacons guiding the algorithm. But for a deeper understanding of the articles' meaning, it's important to know the context, in which these words are used. This can be done using more complex algorithms and methods.

We selected 15 major English-language online media, which from January 2014 released no less than 500 articles about Ukraine. In the sample, there are news agencies (Associated Press), broadcasters (BBC), business media (The Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg), and newspapers (The New York Times, The Washington Post). The are 9 online media from the US and 6 from the UK.

| MEDIA | COUNTRY | Number of Articles |

| Reuters | UK | 6459 |

| Ukraine Today | Ukraine | 5176 |

| The Daily Mail | UK | 2233 |

| Russia Today | Russia | 1770 |

| Bloomberg | US | 1359 |

| Business Insider | US | 1069 |

| The Guardian | UK | 1067 |

| The Wall Street Journal | US | 1046 |

| The New York Times | US | 999 |

| The Washington Post | US | 732 |

| Associated Press | US | 728 |

| The Financial Times | UK | 662 |

| Fox News | US | 620 |

| BBC | UK | 618 |

| The Huffington Post | US | 597 |

| ABC News | US | 594 |

| The Telegraph | UK | 574 |

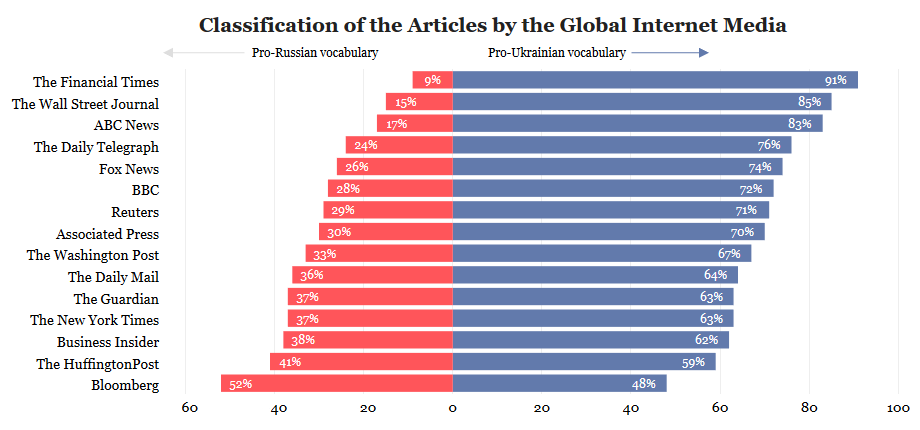

The texts were classified using logistic regression5. This algorithm is popular for solving problems of classification of text data, is easy to implement, and works efficiently with many features.

The results of the classification show the obvious asymmetry towards pro-Ukrainian vocabulary. Let's pay attention to the Western business media only. There's a marked difference between The Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal, on the one hand, and Bloomberg — on the other. Bloomberg articles were split almost 50 / 50 between the categories. This can be explained by the fact that Bloomberg journalists frequently use such discriminatory words as "sanctions" and "debt", which are more likely to be used in the Russia Today articles.

Let us stress once again that we don't know for sure, in which contest these words are used — anti- or pro-Ukrainian. This would require a semantic analysis of the texts, and this is a task for a further study.

For each article, we've calculated the odds of belonging to a particular category. For example, an article in The Washington Post by Ralph S. Clem, professor at Florida International University, titled Why Eastern Ukraine is an integral part of Ukraine with a 99.9% probability belongs to the category of articles with pro-Ukrainian vocabulary. The author refutes the claim that eastern regions of Ukraine have historically been an ethnic part of Russia.

On the contrary, a Bloomberg article by Richard Weiss and Alan Levin, titled Ukraine Joins North Korea as No-Fly Airspace Trouble Spot with a 99.9% probability is classified as having a pro-Russian vocabulary. The article says that a part of eastern Ukraine was declared a no-fly area after the MH17 plane crash. The author stresses that this is a rare restriction currently shared only with North Korea. The article also describes the situation with flights over Iran, Syria, and Libya.

The situation with the articles, the odds for which is in the range of 90-100%, is intuitive. But what if the probability of an article belonging to the pro-Ukrainian category is 50.1%? For the algorithm, everything is clear — the probability is more than 50%, therefore, the article belongs to the pro-Ukrainian category. However, from the reader's point of view, it's not so simple. We'll leave out the mathematical analysis, but we'll note that such articles shall be called borderline.

Let's say that for borderline articles, the probability is in the range of 40-60%. It's difficult for the classifier to place such an article in a particular category. One of the reasons is that these texts don't contain words used by Ukraine Today or Russia Today. The number of borderline articles in the analysed sample is insignificant — 2,7-6,5% of the total number of articles for each online media. The number of articles with a probability of 90-100% is on average 73% of the total number of articles. Further steps of the studies suggest an in-depth analysis of each of the categories. For example, a latent semantic analysis and sentiment analysis.

Let's briefly summarise what's been said in the article. First, there are three times less articles about Ukraine on Russia Today than on Ukraine Today, but they are three times longer. It means there are differences in editorial policy of the two media resources. Second, the vocabularies used by Ukraine Today and Russia Today are different. There are discriminatory words — so called dividers, which help identify to which resource an article may belong. For example, if an article contains the words "separatist", "occupation", or "annexation", it's more likely to belong to the pro-Ukrainian category. And, third, the results of classification of the world's media articles show an obvious asymmetry towards pro-Ukrainian vocabulary.

Identification of fake news is a promising area of the use of machine learning. Tim O'Reilly, founder and CEO of O'Reilly Media, rightly points out, "the essence of algorithm design is not to eliminate all error, but to make results robust in the face of error. Much as we stop pandemics by finding infections at their source and keeping them from finding new victims, it isn't necessary to eliminate all fake news, but only to limit its spread."