In a recent report, IMF recommends that Ukraine switches to inflation targeting where the target range is 3 to 5 percent per year. Is this a reasonable regime for monetary policy in Ukraine? This blog reviews some issues related to this question.

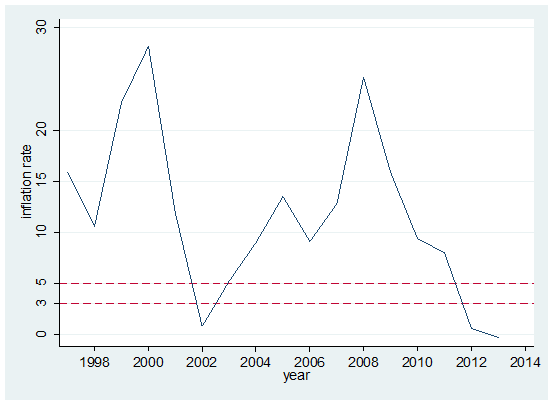

Ukraine has had chronic problems with inflation. In the early 1990s, inflation rate in Ukraine was in thousands of percent and this hyperinflation damaged the economy considerably. Since then inflation subsided but it remained relatively high and volatile (see figure below). Even in recent history, inflation in excess of 10 percent was not unusual. While the previous government of Viktor Yanukovych took credit for near zero inflation in 2012 and 2013, this was far more likely to be a manifestation of depressed economy and overvalued exchange rate.

Figure 1. Inflation in Ukraine

High and volatile generates serious distortions. The experience of other transition countries suggest that inflation targeting may be effective in solving this problem. However, there are a few challenges in implementing inflation targeting.

First, establishing credibility is central for successful inflation targeting. Ukraine’s economy is hit by large shocks (e.g., gas prices set by Russia, violence in the East of Ukraine, uncertainty about the status of Crimea) and it likely to go through high turbulence in the short and potentially medium run. Furthermore, responding to these large shocks will require large movements in the policy instruments such as short-term interest rates. Can the National Bank of Ukraine control inflation in the narrow range of 3-5%/year? Historical record is not particularly encouraging here. Hence, the central bank should set modest goals in the short/medium run but make these goals increasingly aggressive as it builds reputation.

Second, people and businesses in Ukraine lived through high inflation and so inflation fears are strong. This is why the public pays enormous attention to the movements in the nominal exchange rate as these movements can signal inflation. By focusing on an inflation target (domestic prices) and allowing free capital mobility, the central bank cannot control the nominal exchange and interest rates at the same time (classic trilemma). One may worry that the public may interpret changes in the nominal exchange rate as signs of inflationary policies of the central bank and thus can destabilize markets and generate panics. A possible solution could be temporary capital controls which should be lifted as inflation expectations of people and businesses are anchored.

Third, why do you want to have a positive inflation rate and what numeric target should a country like Ukraine have? The standard arguments for a positive inflation target are

It helps to solve downward stickiness of wages (that is, workers are really averse to nominal wage cuts and so the only way to adjust wages is via inflation which gradualy reduces real wages paid to workers);

It helps to avoid zero lower bound when all sorts of bad things can happen (e.g., monetary policy cannot be used to stabilize the economy; deflation; think of Japan in the last 10-20 years).

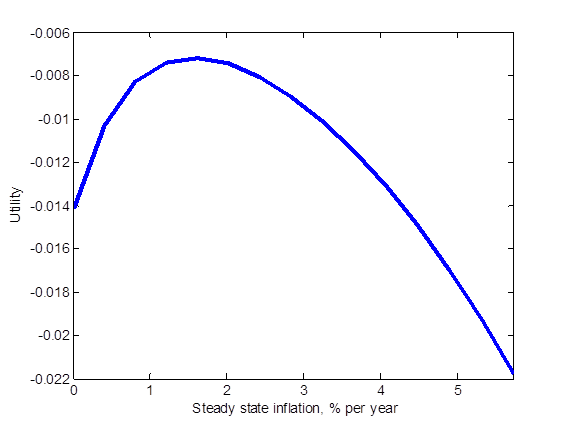

The main costs of positive inflation are dispersion of prices and increased macroeconomic volatility. Hence, there is a tradeoff and the optimal rate of inflation depends on relative strength of these forces. The figure below is taken from Coibion et al. (2012; ungated) who study this question for the U.S. They find that the optimal rate for inflation, which maximizes utility, is about 1.5%/year for the U.S. and this numeric target is robust to a broad spectrum of alternative assumptions. Should the optimal inflation rate be higher for a transition economy like Ukraine?

Figure 2. Welfare as a function of inflation

It seems that the answer could be that the inflation rate should be lower. First, the labor markets in Ukraine are fairly flexible and workers have little bargaining power so that imposing nominal wage cuts is not impossible. Second, a higher nominal interest rate reduces the risk of binding zero lower bound on nominal interest rate. The equilibrium nominal interest rate r=(1/β-1)+γ+π, where β is the time preference parameter, γ is the growth rate of productivity, and pi is the inflation rate. Beta is usually close to one and is typically set at 0.96. γ is fairly low in most countries (about 1 percent per year), but it can be quite high for countries that are catching up. For Ukraine, this can be as high as 4. Policymakers do not control β and γ and so they have to set π sufficiently large to ensure that nominal interest rates do not hit zero. However, the need to set a high π is reduced when g is large. If one takes the U.S. economy and set γ to 4%/year, then the optimal inflation rate is close to zero.

The only reason why inflation could be higher is because shocks may be very large. How large they are going to be for Ukraine is an open question. Suppose we set γ =4%/year and vary the size of the shocks in the model that is described and calibrated in Coibion et al. (2012; ungated). The figure below shows that the peak of the welfare function shifts from π=0.4%/year to π=3.2%/year when we double the size of shocks. If we triple the size of shocks, the optimal inflation rate is 5.7%/year. One can reduce the size of the inflation target by imposing a more aggressive response to inflation.

Figure 3. Welfare as a function of inflation target for alternative sizes of shocks

Obviously, extrapolating a U.S.-calibrate model to Ukraine could be a stretch but these calculations are suggestive. The inflation target of 3 to 5 percent may be reasonable given the volatility of shocks.

Застереження

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations