The Euromaidan events catapulted the previously marginal radical right party, All-Ukrainian Union Svoboda (the “Freedom Party”), to its short-lived prominence. Representatives of the Svoboda party have occupied cabinet posts in the interim government, which has increased anxiety among pro-Russia leaders and citizens. Yet, in the October 2014 elections, Svoboda’s electoral support was halved and, by a narrow margin, the party failed to cross the five percent threshold needed to obtain seats in the parliament. It is yet to be seen whether this merely represents a temporary setback for the party or its demise.

The most recent electoral results do not diminish the fact that, in 2012, Svoboda amassed over ten percent, which is a noticeable electoral result for a radical right party [1]. What explains its success? Scholars have attributed Svoboda’s 2012 achievement in the parliamentary elections to a complex set of factors, including: dissatisfaction with the major parties, protest voting against President Yanukovych, anxieties associated with the 2012 language law, resonance of anti-establishment appeals with the voters, disappointment with economic and political corruption, xenophobia, economic downturn and the re-emergence of pre-war legacies [2].

Although these explanations advance our understanding of Svoboda’s recent electoral success, little is still known about why voters supported Svoboda and the degree to which xenophobia played role in voting decisions. One might presume that anti-Russian sentiment drives Svoboda support. However, using an original survey conducted in 2010, I show that support for Svoboda was rooted less in extreme levels of xenophobia vis-à-vis Russians, and more in economic anxieties and fears of loosing sovereignty.

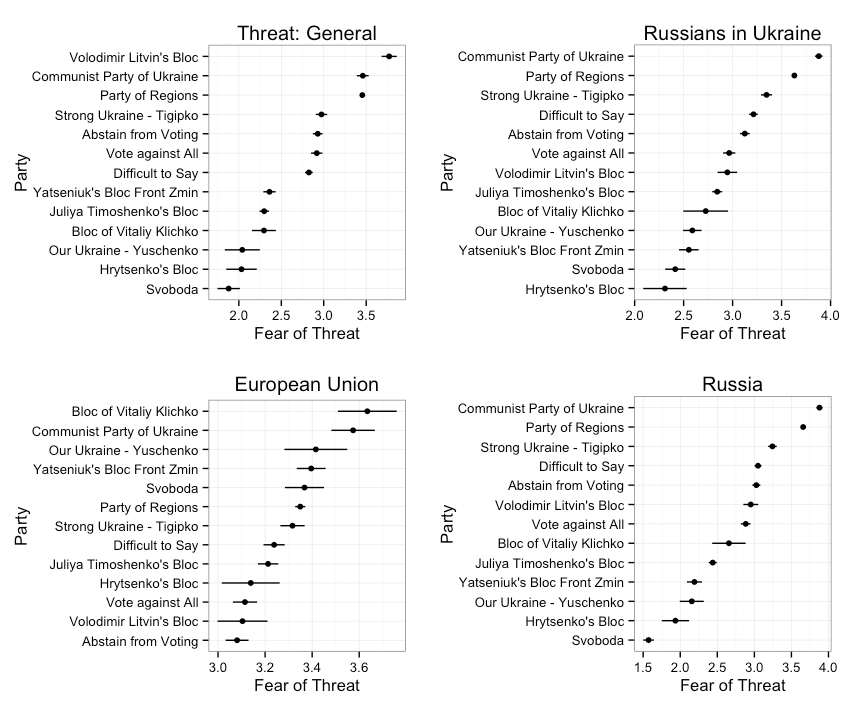

Figure 1 shows substantial differences across distinct sovereignty threats. Fear of general sovereignty threats was already high in 2010, at least among half of the parties. Figure 1 disaggregates sovereignty threats into three specific sources of threats, two from abroad and one domestic. Sovereignty threat from Russia polarized the respondents to a much greater degree than sovereignty threats from Russians in Ukraine since voters embrace less centrist positions on threats and the extremes are further apart. The European Union is not feared at all: all respondents agree that the EU is not a danger to the Ukrainian sovereignty and this position holds for all types of political attachments.

Svoboda voters fear Russia and fear Russians in Ukraine. However, heightened fears of Russia clearly separated Svoboda voters from all other voters (Figure 1). Svoboda voters are unique in their view of Russia as a sovereignty threat, but they are not extreme in viewing Russian citizens of Ukraine as a threat. Among Svoboda voters, fear of Russia is high and unique, while their fear of Russians in Ukraine is high, but not unique, since voters of other, ideologically similar parties, exhibit similar levels of fear.

Figure 1: Sovereignty Threats by Parties

Means with weighted bootstrapped standard errors. Scale: 1 – agree that sovereignty is threatened, and 4 – disagree. Source: Bustikova, 2010

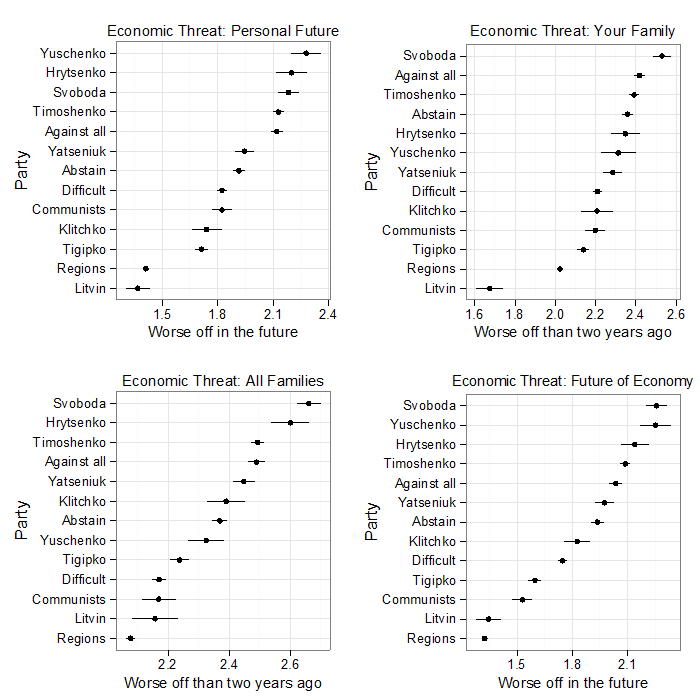

Is Svoboda support driven by economic anxieties? The results unequivocally show that Svoboda voters fear economic threats (Figure 2). Svoboda voters stand out in two aspects: they are distinct in agreeing that their family is worse off than two years ago, and that all Ukrainian families are worse off than two years ago. At a personal level, Svoboda voters expect to be worse off in the future.

The sense of economic depravity among the Svoboda voters is profound. There is a twenty percent gap between Svoboda voters and all other respondents in their (average) perception that their family financial situation has recently deteriorated. Responses to questions about economic threats indicate that Svoboda voters come from a pool of voters who deeply fear exposure to economic insecurity at the personal, familial and societal level (Figure 2). If support for Svoboda is driven in part by economic anxieties, we should expect that a deteriorating Ukrainian economy will expand the voting base for the radical right, all else equal.

Figure 2: Economic Threat Perception by Parties

Means with weighted bootstrapped standard errors. Scale: 1 – better, 3 – worse off. Source: Bustikova, 2010

The survey has shown that concerns about the state’s policies and fears about sovereignty threats trumped identity animosities. These findings should provide pause to claims that, at the core of Svoboda support, is a disproportionately high level of animosity against other ethnic groups in Ukraine, and that Svoboda represents an extreme xenophobic and “fascist” force in Ukraine. Although the levels of inter-group hostility were very moderate in 2010, the fact that they polarized the political system has contributed to the escalation of perceived identity threats.

The survey shows that Svoboda voters feared Ukrainian Russians more than the voters of other parties but, overall, the fear was very mild, yet in the case of Svoboda, distinct from other voters. During peacetime, this suggests that the Russian “fifth column” has strong potential to radicalize the radical right electorate. Given the outcome of 2014 elections, In light of turbulent events, parties that demonstrate military competence and the ability to preserve Ukraine’s territorial integrity have the upper hand and have siphoned Svoboda’s supporters away. In times of crisis, physical security issues force the electorate to coalesce behind strong-armed leaders, not parties with a niche appeal.

Notes

[1] The average vote shore for radical right parties in Eastern Europe (based on 93 elections) is 6.5%. If we exclude countries where radical right parties do not exist, the average vote share is 7.7% (Source: Bustikova 2014).

[2] Cantorovich, 2013; Kuzio, 2007; Likhachev, 2013; Moser 2014; Polyakova, 2014; Shekovtsov, 2011; Shekhovtsov, 2015; Umland, 2013; Umland and Shekhovtsov, 2013. The Svoboda party has been characterized an ethno-centric and anti-Semitic party: “Svoboda is a racist party promoting explicitly ethnocentric and anti-Semitic ideas. Its main programmatic points are Russo- and xenophobia as well as, more recently, a strict anti-immigration stance. It is an outspoken advocate of an uncritical heroization of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists – an interwar and World War II ultra-nationalist party tainted by its temporary collaboration with the Third Reich, as well as its members’ participation in genocidal actions against Poles and Jews, in western Ukraine, during German occupation. Although Svoboda emphasizes the European character of the Ukrainian people, it is an anti-Western, anti-liberal, and anti-EU grouping” [Umland 2010: 1].

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations