Ukraine should not repay the infamous $3 billion Yanukovych bond. However, its current ‘wait and see’ stand dependent on an uncertain IMF decision is not a strategy. I argue that Ukraine should instead take the initiative and go on the legal offensive in the highly supportive international legal environment and use the political capital accruable to the victim of the aggression not only for requesting financial handouts and bailouts, but to directly confront Russia through soft power of bond litigation.

Preface and Argument

The mainstream scenario of the current Ukraine foreign debt restructuring (e.g. see Bloomberg and Timothy Ash), including the $3 billion Yanukovych (also known as ‘booby trap’) bond maturing in December 2015 (reportedly on the balance sheet of Russian National Wealth Fund (NWF) and acquired through the Irish Stock Exchange), puts the spotlight on the future IMF decision ‘of lending into arrears.’ It goes as follows: (a) Ukraine does not pay, (b) Russians press for the default, and (c) the IMF Board decides what to do next.

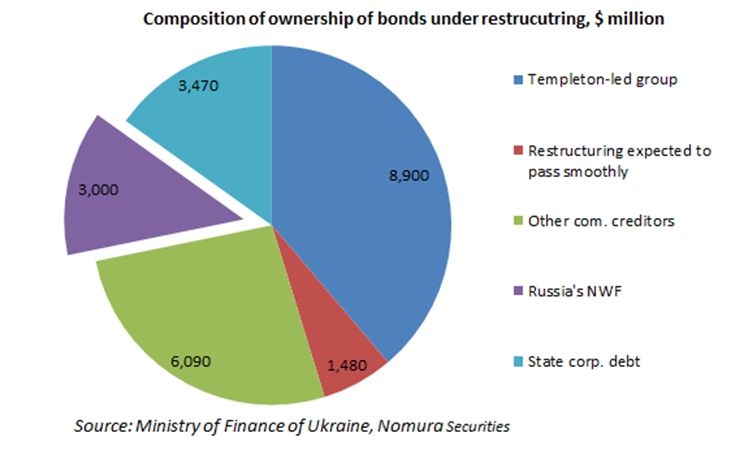

Hence, the future IMF decision becomes a crucial element of the deal with the Templeton-led creditor group, which reached agreement with Ukraine on August 27, 2015, and has to address a case in which NWF does not agree to match the terms accepted by other bondholders with ca. $19 billion worth of debt (the Templeton-led group represents approx. $9 billion in holdings). The transaction is expected to close in late October. The closure will probably also require guarantees that the Yanukovych bond would not get a preferential treatment.

Both PM Yatseniuk and Finance Minister Jaresko stated that they expect the Yanukovych bond to be restructured in line with and on the same terms as other participating debt. Russia’s Finance Minister Siluanov representing the NWF Board was quick to react: NWF would not join the deal reasoning that NWF considered the bond official government-to-government debt.

I argue that Ukraine should not pay and should pursue one or a combination of legal offensive and defensive options to secure debt relief. I will outline what these could be, drawing on the recent proposals by Anna Gelpern of Georgetown University, Mitu Gulati of Duke University, and Mark Weidemaier of the University of North Carolina, in the hope that a public discussion thereof may lead to Ukraine’s informed choice.

The Slick Bond

The ‘booby trap’ bond was a part of the $15 billion rescue package offered by the Kremlin to former President Yanukovych, who in 2 months following the sale of the first installment fled to Russia and is now under investigation for large-scale corruption and ordering mass murder of protesters during Euromaidan, an uprising that was triggered by the then President’s sudden refusal to sign the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU in exchange for a lifeline thrown by Moscow to lure Ukraine into the Russia-led Eurasian Union .

The bond got its (the ‘booby trap’) name for the unprecedented in the recent history creditor protection clauses structured to keep the debtor on a tight leash. Apart from the extremely unusual for a sovereign borrower’s obligation to keep its leverage below 60% of GDP the prospectus of the Yanukovych bond also contains remarkable clauses that stipulate that any debt ‘owed to the Noteholder or to any entity controlled or majority-owned by the Noteholder’ is subject to cross-default. The latter puts on par any debt owed to Russia, NWF, Gazprom, Sberbank, and other entities controlled by the Kremlin rumored to hold over $2 billion in Ukraine’s sovereign debt obligations on top of the booby trap bond.

Furthermore, the Russians reserved the right to treat the NWF bond as both a commercial holding (which was the case in 2014) and invoke its official designation (predominantly this year) whenever the Kremlin thought fit (see here and here). To qualify for a bilateral official debt, however, the bond had to be registered with the Paris Club – and, as there was no mention of it in 2013 report, it obviously was not. Due to the quirky bond structure, both designations are indeed possible, but the duality according to Mark Weidemaier in case of litigation may easily become more of a liability than an asset to Russia.

Litigate?

The current political and legal environment is Russia-unfriendly and offers ample opportunities to use the political capital accruable to the victim, that is Ukraine. G7 on various occasions condemned Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and its members continue to move in lockstep increasing pressure on Russia by way of sanctions in support of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The change in legal environment vis-à-vis Russia in the course of 2014 alone was striking. For example, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) delivered 129 judgments against Russia, including ruling that Russia was to pay Yukos shareholders more than $2 billion ‘in respect of pecuniary damage.’ The Court for Arbitration in the Hague ordered a record compensation of $50 billion to former Yukos shareholders for forced bankruptcy and transferring its assets to Rosneft. Austria, Belgium, and France have begun freezing Russian assets to enforce the decision (see here and here )… And the UK moved to reinstate a legal inquiry into the 2006 polonium poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB officer, who exposed linkages of the Kremlin to international organized crime.

In light of above, Ukraine should consider embarking on a legal offensive path too. The immediate goal would be to secure an injunction on payments under the Yanukovych bond, halting any and all transfers thereunder preferably until the time the Ukraine’s sovereignty is restored. Ukraine does not need to win, but simply dispute in good faith, so the bond is treated as ‘disputed debt’ and the IMF ‘lending into arrears’ moment is avoided .

Some of the sensible ideas and recent proposals are summarized below:

- Mitu Gulati proposes to invoke the odious debt concept. He points out that there are many similarities to the Great Britain vs. Costa Rica case of 1923 when the Supreme Court Chief Justice William Taft ruled to reject enforcement of debt claims entered into by the dictator and kleptocrat, who had fled the country (here and here ).

The problem with odious debt is that it is a difficult sell in litigation. Even though President Poroshenko said in June that the bond was in essence a bribe, a part thereof, even if miniscule, may have actually been used to procure public goods, and there lies the stumbling block.

Further complications are that shortly after President Poroshenko’s use of the term, Yanukovych was mysteriously removed from the Interpol wanted list signaling that the evidence that had been presented against him may not had been bulletproof. The Prosecutor General’s Office immediately launched a renewed effort into the probe, but the prospects of a sudden breakthrough seem unlikely.

- Anna Gelpern extends Mitu Gulati’s argument above and proposes an extension package she calls the ‘Debt Sanctions,’ i.e. odious debt supported by political stand to plug legal gaps. As a primer and a precedent thereof Dr. Gelpern refers to the US initiative in Iraq to write off Saddam Hussein-era debts to protect its oil and gas sector from vultures. An abstract from Anna Gelpern’s remarkable post of March-2014 discusses debt sanctions application to Ukraine:

‘The contracts are mostly standard form… Even so, English courts may not have much sympathy for Russia. They may decide that invading a country, bankrupting it, and trying to collect would be too distasteful with or without Odious Debt…

If the British parliament chooses to pass a law to this effect, it would have ample precedent…

An “odious bond” law could be criticized as a biased power play—but in that, it would be no different from traditional sanctions, though it would probably be more effective than most traditional sanctions. Might Russia retaliate with a law against US and European loans to Ukraine? It would be too embarrassing. None of the other governments lend under Russian law, and this would only serve to highlight the fact that even Mr. Putin prefers English law when it comes to debt contracts.’

- A straightforward setoff application: any state-owned corporation with a history of international financial audits and valuations by the reputable auditors and consultants available at the time of Crimean Anschluss and consequent takeover of assets by Russia would do (e.g. Chornomornaftogaz). Or, as Dr. Gelpern proposes, why not simply use Sebastopol’s Black Sea Fleet lease Russia has been in breach of from 2014?

The problem with the setoff is that it is generally prohibited by the terms of the bond as Joseph Cotterill at FT Alphaville points out (another slick provision made with an annexation in mind?).

- Finally, Mark Weidermaier makes a powerful argument that impracticability and fraudulent inducement concepts can and should be used by Ukraine with respect to the ‘booby trap’ bond:

‘If we’re talking about a private investor holding non-GDP linked bonds, it’s easier to see the conflict with Russia as just one of many background risks that might make it hard for Ukraine to repay. Generally, investors don’t take the risk that such risks will materialize; those are presumptively assumed by the borrower. Plus, I doubt a court would want a rule that discourages investors from lending to countries that are at risk of this kind of conflict. Russia, though, explicitly structured its loan to go into default if GDP dropped below a certain threshold. Seems to me there are two ways to interpret that. First, both Russia and Ukraine assumed armed conflict would not break out. That’s the impracticability scenario. Second, Russia was planning to instigate armed conflict if necessary to advance its interests in the reason. That sounds like fraudulent inducement…’

If one assumes that (a) Yanukovych could get all $15 billion from the Kremlin; (b) From 2012 the hryvnia was overvalued against the greenback and Russia’s Sberbank and VTB subsidiaries’ budgeted for FY2013/2014 based on 35% hryvnia devaluation were indicative of the scope; and (c) Former Putin Advisor, Andrey Illarionov, was indeed right in saying that Crimea takeover operation had been under development for over a decade, the 38% debt to GDP ratio at Kremlin lifeline inception would turn into 65% after the package has been funded and devaluation has taken effect. Crimean annexation deduction to GDP and failing economy due to consequent disruptions would come as bonus points.

Alternatively, by doing nothing and waiting for the IMF to make a decision, Ukraine risks to end up with a solution that may not be in its best interest (e.g. a $2.5 billion payment can be guessed from the aggregates presentation in the initial IMF EFF Program of March-2015).

Consider a similar outside brokered deal of November-2014 when the EU wanted to secure the winter natural gas supply and had insisted that Naftogaz paid Russia $3.1 billion allegedly owed to Gazprom. This was approx. equal to 0.7 months worth of imports at the time when the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) forex reserves were already dry at less than 2.5 months of imports. As a result, Ukraine effectively funded the country that was responsible for killing over 4’000 and for heavy injuries of another 10’000 Ukrainian citizens, and 450’000 displaced persons at the time. Moreover, this decision put the NBU and the entire economy on the brink with delays of up to 5 weeks in forex transactions, evaporation of liquidity in the real sector, and a myriad of bankruptcies.

If worst comes to worst and the IMF insists on the payment in January-2016 as the EU did in November-2014 (the difference would be that as of August-2015 there were over 6’800 dead, 17’000 having incurred heavy injuries, and 1.4 million displaced.), I strongly feel that a 2008 Ecuador-style selective default (Ecuador defaulted on 2012 and 2030 issues declaring them “illegal and immoral” while other debts continued to be serviced) may be better than pursuing a morally ugly, politically unpopular, and economically detrimental IMF induced decision.

But it does not have to be this way! Ukraine has enough tools and arguments to proceed with a legal offensive with a significant probability of success in today’s political and legal environment that would most certainly be applauded by both current debtholders and the IMF.

Annex. Diagrams 1 and 2 below put Yanukovych bond in the context of Ukrainian debt payments. The data used for construction of diagrams do not take into account the restructuring deal struck on August 27th, 2015.

Diagram 1.

Diagram 2.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations