More than 25 years have passed since the first Parliament resolution “On land reform”. Despite this significant time period, the reform is far from being complete: sales market for agricultural land does not exist, significant share of the rental market is informal and several categories of land do not have a clear legal status or are used in a non-transparent way.

Weak land governance precludes realization of Ukraine’s comparative advantage and its attractiveness for outside investment in agriculture and beyond. Full realization of its agricultural sector, especially in ways that include small and medium scale producers, is possible only if land tenure is secure for the long term and land rights are transferable. As Ukraine is one of the major global exporters of agricultural outputs, quality of land governance in Ukraine has implications for global food security. We highlight the directions for further reform in the land sector that may produce the most significant impact on agricultural productivity and growth in 2016-20 and beyond.

About 71% of Ukrainian territory (42.7 mln. ha) is classified as agricultural lands. State owns about 10 mln. ha of this land, which comprises 25% of Ukraine’s agricultural land base. There are about 23 mln private land owners and users (about 90% of them are natural persons) and about 4.9 mln users of state land. About 21.5 mln ha of agricultural land is cultivated by about 45,000 commercial producers (about 36,000 of which are below 200 ha). Thus, the quality of land governance affects wellbeing of a significant portion of country’s population and efficiency of several industries that use land as a factor of production and are vertically integrated with such industries.

Land governance in Ukraine has been criticized for slow pace of reforms, limiting constitutional rights of land owners, corruption and inefficiency (as summarized in WB LGAF Report, 2013). Pilot results of Land Governance Monitoring implemented in 2015 by the WB funded Project “Capacity Development for Evidence-Based Land & Agricultural Policy Making in Ukraine” jointly with MoAPF, State GeoCadastre, MoJ, State Fiscal Service and several other government authorities portray the current state of land governance at local (rayon/ city) level and establish infrastructure for tracking progress with land reform.

Results of the monitoring for 2014-2015 show that:

- the level of registration of state land is significantly lower than that of private land (24% vs 71%) which is a source of non-transparent practices. The completion of the State Registry of Rights for Real Estate is much lower and includes only 20.9% of the number of records in the Land Cadaster;

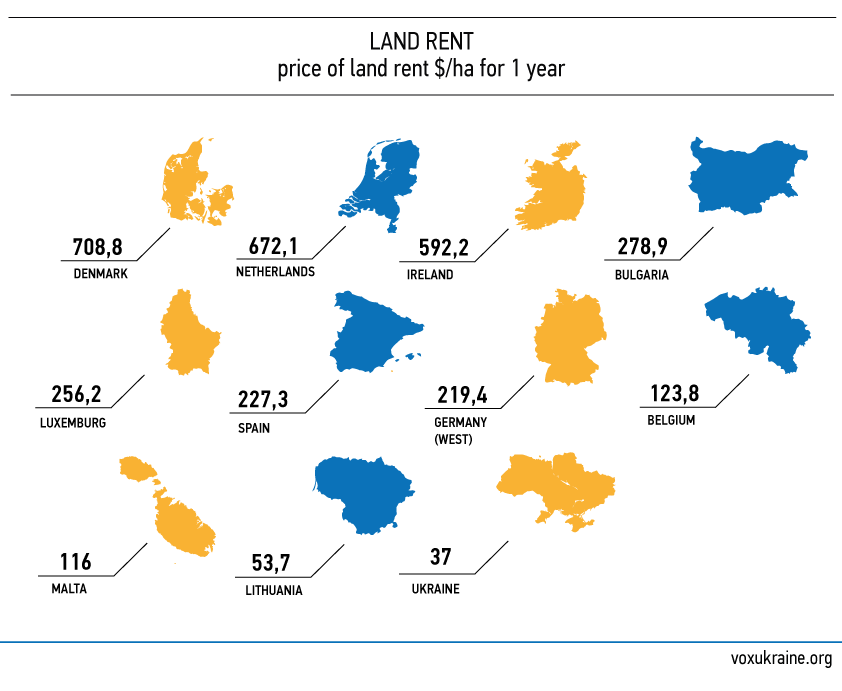

- the rental price for agricultural land is one of the lowest in Europe and CIS countries (about 37 USD in 2015) reducing the wellbeing of rural land owners and providing for inefficient use of land resources;

- the sales market for land (outside of Moratorium for agricultural land) is extremely thin primarily due to lack of financial instruments and difficulties with using property as a collateral. The primary type of transactions for agricultural land is rent (about 4.7 mln rental agreements with average duration of 7.6 years) with substantial informal rental market;

- the number of taxpayers for land tax (about 7.3 mln) is substantially lower than the number of private land owners and land users.

Key issues with protection and transferability of rights that cause the above problems are different for each of three type of land property (private, state, communal). Besides these types, there are types of land with de-facto unclear legal status.

Governance of Private land confronts the following difficulties:

- Incompleteness of the Land Cadaster and errors in Cadastral records establish an extra cost for transactions and is a source of insecurity of rights.

- The Moratorium for sales of agricultural land limits transferability of private agricultural land, violates the constitutional rights of land owners (most of them are old age), restricts access to finance, puts downward pressure on the rental prices and, thus, limits development of rural areas (both agricultural and non-agricultural sectors).

- Restriction on minimum duration of rental agreements to 7 years was established in 2015 and about to be extended to 10 years for irrigated land. It effectively moved the short-term rental transactions to informal sector limiting protection of rights of tenants and land owners. According to the MoJ, the number of formal registrations of rental rights dropped from about 150,000-200,000 registrations per quarter to 35,000-40,000 registrations immediately after establishing this regulation.

Management of State land can be described as follows:

- Conflict of interest is created by accumulation of registration function and function for management of state land within one organization – State Service for Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre. Such combination of functions provides opportunities for non-transparent practices and reduces incentives for registration and more effective management of state land.

- Low level of registration of state land in the Cadaster provides opportunities for land grabbing, non-transparent land use and corruption. The low registration of state land, however, is driven primarily by non-agricultural land (e.g. forests). Regarding the agricultural land, out of 10.5 mln ha of state land about 5.5 mln ha are arable. About 2.5-3 mln ha are formally rented out (primarily without auctions), about 1 mln ha are in permanent use by state enterprises and Academy of science. The use of the remaining agricultural state land is unclear.

- Land was provided in permanent use to state enterprises and some former collective farms, creating incentives for informal rent via joint cultivation and other arrangements. State farms show losses and receive support, while payments for rent and sub-rent stay un-accounted for.

Communal (municipal) land is a form of property, which becomes more and more important with the progress of decentralization in Ukraine. However, several significant issues affect this land:

- Demarcation of boundaries of towns, villages and other settlements is incomplete (only 50 settlements out of 29,772 had formally registered boundaries by the end of 2015), which undermines the legitimacy of any decisions regarding land allocation made by local councils. It undermines investment climate and is a source of land conflicts in several regions. The process of establishment of new administrative units – hromadas – adds complexity to the boundary issue.

- The low level of registration in Cadaster of communal land provides opportunities for non-transparent practices and leads to foregone opportunities in terms of development and local budgets revenue. All state land within the urban settlements (except land under the state enterprises) was already transferred to communal property, however remains outside the Cadaster and Registry, which makes the rights of tenants and users of such land weak and rental transactions non-transparent and local government unaccountable.

Collective land represents a non-constitutional form of property, which is inherited from the time of collective farms. No formal transactions or registration is possible for this type of land, which provides opportunities for informal (illegal) land use. Also, informal status of this land prevents a clear demarcation of the adjacent parcels, which creates an additional transaction cost and provides opportunities for encroachment. Several types of land belongs to this category. Among them are: field roads (about 4.8% of farmland were allocated to field roads during the privatization, which is about 1.3 mln ha), farm yards, unclaimed privatization parcels (shares) (about 5% of parcels are unclaimed), forest wind breaks. As a result, about 2-3 million hectares stay out of formal economic turnover providing resources for informal sector.

Land with unclear legal status includes Unclaimed property. It is a growing issue, which leads to unauthorized (illegal) or inefficient use of land. There are two types of property in this category: unclaimed inheritance (estimated land in this category is between 1 and 3 mln ha), and land in property of enterprises that were closed up. The Parliament has just passed the Law in September 2016 to address this issue, but practical implementation may take some time and would require resources.

Together, these issues lead to a vicious and self-reinforcing cycle of informality, weak rights, lost budget revenue and reduced agricultural productivity. Lifting the Moratorium on agricultural land sales will not miraculously eliminate these issues. Even in the most optimistic scenario, if the Moratorium is lifted, low-cost efficiency enhancing transactions will be limited to a relatively small part of Ukraine’s land. More importantly, if records are clear and tenure is secure, long-term leases should allow to achieve results equivalent to those from a sales market. With lower upfront capital requirements rental market is potentially much more liquid.

In 2015-16, the Government has taken several encouraging steps. These include (i) development of a Comprehensive Strategy and Action Plan for Agriculture and Rural Development in Ukraine 2015-2020 supported by the National Council for Reforms where land reform features prominently; (ii) tightening requirements for rental rights over state land via auctions; (iii) establishment of an inter-agency committee to monitor land reform and land governance and publication of a report and associated data ranking of rayons; (iv) opening of public access to the Registry of Rights and State Land Cadaster; (v) delegation of the registration function for property and rental rights to notaries; (vi) establishment of e-services for provision of cadastral extracts and property valuation. MoAPF also started to reorganize, liquidate, or privatize many state enterprises which it manages that jointly have about 0.5 mln ha in permanent use. Minister of Agrarian Policy and Food, Taras Kutovyi, has indicated that land reform is one of the top three priorities for the Ministry raising expectations for further significant steps. Finally, the recent change in subordination of Geocadastre has addressed a long standing issue with limited capacity of MoA to implement the land reform, and the Parliament has just passed the Law on land parcels of unclaimed inheritance.

To build on these, a number of actions are needed in the short to medium term (6-12 months):

A. Increasing efficiency of state land management: To use state land as a catalyst for land market reform, rather than a source of corruption and inefficiency, it is necessary to develop, pilot, and monitor the effect of a new legal framework and transparent procedure to clearly demarcate the state land and transfer it out of state ownership by either auctioning or transferring to communal ownership (preferably at rayon level)[1] based on clear criteria, and to facilitate its productive development.

This should go hand in hand with the development and testing of a legal framework for identification of unclaimed property (unclaimed inheritance, property of closed up enterprises) and transferring it to communal property, including interim procedures to register such land in the Cadaster, as well as procedures and legal framework for dealing with collective land (unclaimed privatization shares – pays, field roads, forest windbreaks, collective farm yards).

B. Improving institutional arrangements and transparency of land governance: Measures in this area would include:

(i) improving procedures for registering prices for (rental) land transactions in the Registry of Rights;

(ii) developing methodology for mass valuation of land based on market prices;

(iii) linking land tax records to cadastral data to assess tax collection efficiency and identify opportunities for greater collection of own-source revenue by local authorities;

(iv) sustain and deepen regular monitoring of land governance (including monitoring of land prices and discrepancies between actual and designated land use) by establishing a normative base for it.

C. Testing, monitoring, evaluating and improving efficiency of land reform: This would include:

(i) working with banks and agribusiness to develop and test financial instruments to support access to finance in the agricultural sector and remove obstacles for using land as a collateral;

(ii) improving awareness on land rights and land information access among landowners, land users, local government authorities and other stakeholders;

(iii) capacity development for management of land resources at local (village and rayon levels);

(iv) establishing clear requirements and procedures for development of local land management plans.

Longer term reforms (1-3 years) to fully harness Ukraine’s comparative advantage in agriculture would include:

(i) deregulation of rental transactions;

(ii) improving protection of rights of tenants and land owners by registration of rental rights;

(iii) simplifying procedures for error corrections in cadastral and registry records;

(iv) roll out of the verification & completion of cadastral records for state and communal land;

(v) opening up of the sales market for private agricultural land based on the experience gained in auctioning off the state land. Restrictions on the maximum size of individual ownership and on access of foreign residents are likely to be imposed for the transition period of 3-5 years. A decentralized approach for lifting the Moratorium may also be considered.

In summary, despite of 25 years of reforms a lot yet has to be done. Many of the above reforms are not related to highly politicized issues (e.g. lifting the Moratorium) and would depend only on the political will of the Parliament and Government. Improving the governance of land resources is expected to improve agricultural productivity and wellbeing of land owners and land users, and will stimulate development of rural areas.

Notes:

[1] Villages lack formally registered boundaries, technical capacity to manage land and market power to negotiate with large land owners and users.