In recent decades, the number of both formally and actually independent central banks around the world has grown significantly. At the same time, industrial policy—defined as government support for specific sectors or companies—has proven ineffective. Are central banks to blame? And can a government still pursue industrial policy in the presence of an independent central bank?

Central bank independence is a crucial institutional response to the challenge of creating trust in national currency. Over the past 30 years, the independence of monetary authorities in most countries has risen substantially. Advanced economies generally have greater formal and actual independence, while in countries where legal reforms fall short of recent best practices, de facto independence often is even more telling. Emerging market economies have implemented major structural reforms too, advancing economic liberalization, developing financial markets, promoting openness, and strengthening macroeconomic policy frameworks.

It is no coincidence that the sharp decline in global inflation occurred alongside the institutional strengthening of central banks. At the same time, there was a significant reassessment of government intervention in the economy. Between 1990 and 2010, industrial policy lost much of its appeal in light of its controversial results, considerable public cost, and vulnerability to corruption. The benefits of global integration are now considered a more effective path to structural adaptation and development policy than offering targeted incentives to individual sectors or companies.

However, the shift in emphasis from interventionist to market-driven growth strategies does not mean that industrial policy has been abandoned. What began as a thoughtful and comprehensive approach to structural adjustment and the development of complex economic activity often devolved into an ideology opposed to anything associated with markets and macroeconomic stability. Independent central banks came to serve as a kind of bogeyman for unchecked interventionism—both for dirigiste-minded ideologues and for leaders of business groups willing to monopolize corruption rents and prolong their extractive use of public resources. Ukraine offers a clear example of how price stability, banking regulation, and the institutional standing of the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) have long faced pressure from accusations of hostility towards industrial policy.

Is there a valid logic in juxtaposing central bank independence and industrial policy? Yes, if we start from the assumption that price stability, fiscal discipline, and regulatory autonomy pose a challenge to the wasteful enrichment of the wealthy at the expense of the poor. Similarly, there is a reason to see potential conflict between macroeconomic stabilization and the subsidization of “priority sectors” in the style of Latin American industrialization, which ended in episodes of hyperinflation, debt crises, social unrest, and political upheaval.

At the same time, the experience of many countries demonstrates that industrial policy can be a highly sophisticated instrument. Modern industrial policy, for example, often builds on the so-called neo-Schumpeterian approach to economic growth—an evolution of Joseph Schumpeter’s thinking on the role of innovation and creative destruction in development. This approach calls for promoting investment in innovations that would not otherwise take place due to various market failures. It also emphasizes the importance of incentivizing risk-taking associated with innovation. According to the neo-Schumpeterian perspective, the engine of growth is market dynamism—specifically, the emergence of new firms with new products and ideas. Therefore, industrial policy should aim to create space for new businesses rather than prop up old ones. In this context, it is evident that there is no fundamental conflict between industrial policy and independent central banks. On the contrary, monetary authorities are often among the strongest proponents of economic dynamism and flexibility. At the very least, from a political economy standpoint, this is understandable: greater flexibility and dynamism reduce the electoral appeal of pressuring central banks to impose an inflation tax on society for the benefit of some concentrated interests.

The absence of such a conflict is also evident when considering the nature of recent reforms. These have been aimed at strengthening price-stability-oriented monetary policy, reinforcing fiscal rules, improving banking regulation, promoting financial development, restoring public finances, and enhancing debt sustainability. In other words, modern industrial policy no longer relies on the direct use of macroeconomic tools that influence aggregate demand. Instead, it has long been implemented within the perimeter of trade policy, competition enforcement and anti-monopoly regulation, financial development strategies that expand access to capital, intellectual property rights protection, support for research and innovation, and encouragement of market dynamism, among other. Direct government subsidies are structured around programmatic or mission-oriented approaches and are subject to strict democratic oversight through the budget process. The green transition, digitalization, and artificial intelligence are among its key priorities too.

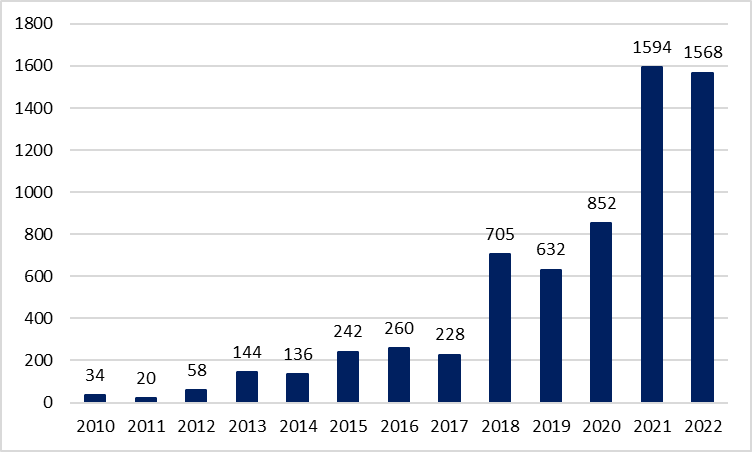

The geopolitical fracture in the global economy has brought industrial policy back to the forefront of government intervention agendas. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, and particularly amid the escalating trade disputes between the U.S. and China in 2018–2019, the number of industrial policy measures adopted worldwide began to rise sharply. Strategic autonomy and the restoration of military capabilities have emerged as new rationales for government intervention via industrial policy instruments. Figure 1 illustrates that over the past 15 years, the number of such measures has multiplied severalfold.

Figure 1. Total Number of Interventions Associated with Industrial Policy

Source: Juhasz R., Lane N., Rodrik D. (2023). The New Economics of Industrial Policy. NBER Working Paper. No. 31538.

It is evident that shifts in globalization dynamics and mounting geopolitical tensions have restored industrial policy stance as a key tool of government intervention. The asymmetric gains from globalization monopolized by a handful of rapidly growing autocracies have undermined confidence in the assumption that trade delivers mutual benefits and ensures peaceful coexistence. Similarly, the rapid concentration of returns from innovation rents—the “winner-takes-all” effect—flowing into the hands of a limited set of technologically-advanced firms have eroded trust in globalization and innovation as effective mechanisms for redistributing income across all social segments. Together, these trends have created fertile ground for a shift in socio-political thinking about the drivers of growth in an increasingly fragmented global economy.

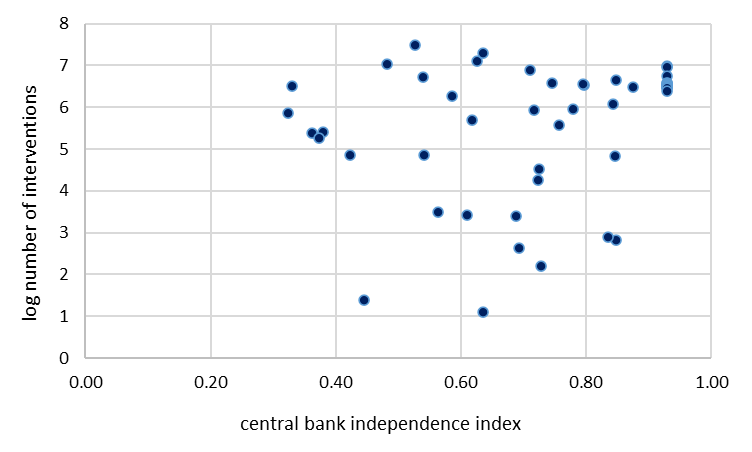

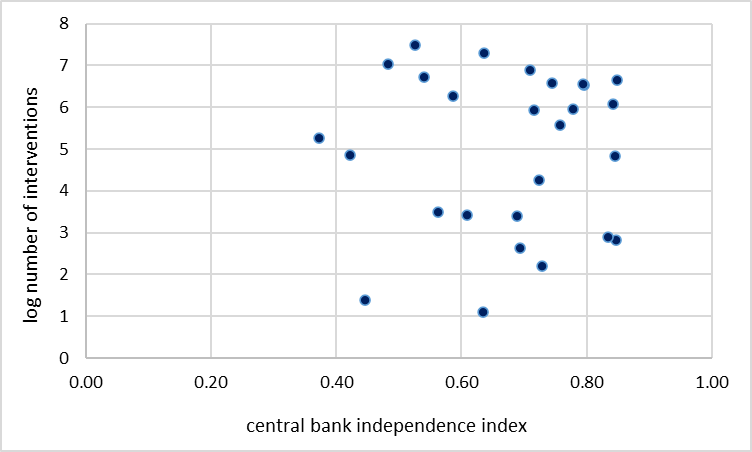

Despite the rapid revitalization of industrial policy instruments in the current context—albeit underpinned by a neo-Schumpeterian theoretical foundation—it is clear that independent central banks do not pose an obstacle. Figures 2 and 3 show no correlation between the number of industrial policy measures adopted (as tracked by the New Industrial Policy Observatory) and the level of central bank independence measured by the Central Bank Independence Index (Romelli, 2024). This finding holds both for the full sample of countries—which includes inflation-targeting economies, the United States, euro area countries, China, and Argentina—and for the same sample excluding advanced economies.

Figure 2. Central Bank Independence and Industrial Policy

Note: Based on data from Juhasz, R., Lane, N., & Rodrik, D. (2023). The New Economics of Industrial Policy. NBER Working Paper No. 31538, and Romelli, D. (2024). Trends in Central Bank Independence: A De Jure Perspective. BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 217.

Figure 3. Central Bank Independence and Industrial Policy in Emerging Market Economies

Note: Based on data from Juhasz, R., Lane, N., & Rodrik, D. (2023). The New Economics of Industrial Policy. NBER Working Paper No. 31538, and Romelli, D. (2024). Trends in Central Bank Independence: A De Jure Perspective. BAFFI CAREFIN Centre Research Paper No. 217.

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate that a more active industrial policy does not compensate for the lower monetary stimulus associated with a highly independent central bank. Countries with both higher and lower levels of central bank independence may engage in industrial policy with different intensity. In other words, countries pursue industrial policy not because independent central banks fail to provide sufficient macroeconomic support but because they possess sufficient institutional capacity to oversee and evaluate the effectiveness of government interventions, along with adequate fiscal resources and regulatory competence.

Countries that lag behind in institutional development typically lack strong monetary institutions and the capacity to implement complex industrial policies. They risk significant fiscal resources due to the high likelihood that industrial policy will be captured by politically connected business groups—an outcome that can threaten social stability. Naturally, higher economic complexity makes using more industrial policy interventions seem more appropriate. This explains why advanced economies are the primary drivers of such measures. In contrast, emerging market economies that are active in industrial policy may have widely varying formal arrangements for their central banks.

If central bank independence does not hinder industrial policy, it is worth asking whether it might, in fact, support it. The short answer is yes. Price and financial stability are especially beneficial for complex industries—both directly, by lowering price dispersion and uncertainty, and indirectly, by maintaining competitive pressure, without which innovation is unlikely to be in demand.

Moreover, low inflation and financial stability contribute positively to financial development by broadening access to funding. However, as the stark contrast in technological innovation between the U.S. and the EU shows, the structure of the financial system, regulatory environment, tax policy, and culture of social redistribution matter more than interest rate levels or the relative “softness” of monetary policy. While central banks do not create Silicon Valleys, they do shape investor confidence in the future macroeconomic environment—a prerequisite for taking risks today.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations