At 10 am on Monday, June 16, 2014, Gazprom, a Russian gas monopoly, cut off supplies of gas to Ukraine. This is the third time in the last ten years when Gazprom has tried to use a cut-off to force the Ukrainian government to accept a deal it did not want to accept. In the previous two cut-offs–in January 2004 and January 2009, that is, in the middle of bitter cold winters–Ukraine bowed to the pressure and agreed to unfavorable contracts with high prices, tough clauses, and heavy penalties.

Each time, Russia used Gazprom and energy prices as a political instrument to pressure pro-Western governments in Ukraine. Although the current cut-off is motivated by the same political factors, the outcome could be different this time.

In a nutshell, Gazprom wants to sell gas to Ukraine at $485 per thousand of cubic meters. Ukraine insists on the price of $285, which was roughly the price Gazprom charged Ukraine under pro-Russian President Yanukovych who fled the country in February 2014. To put these prices into a broader perspective, the current spot price of natural gas in Europe is about $230. The long-term contract price of Russian natural gas for Germany is about $385. Since the cost of transporting natural gas from the Russian border via Ukraine to Germany is approximately $90, the implicit price that Gazprom charges Germany is about $300. In light of these reference prices, it is hard to see how $485 could be a market price for Ukraine.

At any rate, Ukraine and Gazprom did not agree on any middle-ground price and the dispute became a game of attrition. In this game, who is going to win depends on who can outlast the opponent. In contrast to previous gas wars, Ukraine has a much stronger position and may emerge as a (relative) winner.

First, this gas war started in the middle of the summer when demand for natural gas is at its lowest point (there is no need to burn gas to heat houses). Ukraine extracts enough of its own natural gas to cover its needs during the summer time. Ukraine also has 13.5 billion cubic meters of natural gas in its underground reserves. As a result, the Ukrainian government estimates that Ukraine can survive without Russian gas until December 2014.

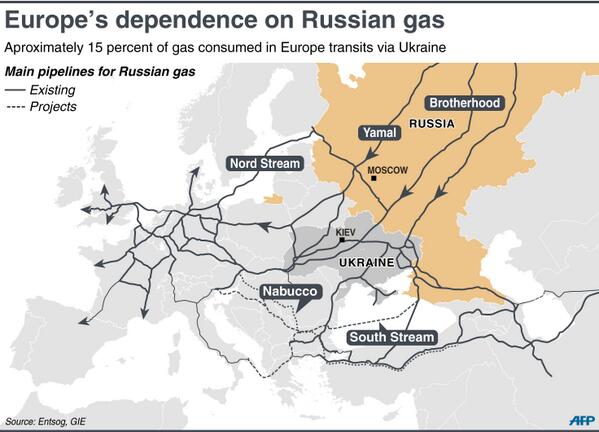

Second, Russia cannot literally stop pumping gas into Ukraine’s pipelines. Figure 1 shows that major pipelines to Western Europe go via Ukraine. The capacity of pipelines outside Ukraine is not enough to meet Gazprom’s obligations in the EU. By shutting down gas supplies completely, Gazprom is going to hurt its customers in Germany, Italy, Poland and many other EU countries. This could be a costly outcome for Gazprom because it will not get a penny of revenue in this case. The reputational costs for Gazprom could be even more severe than a loss of revenue as European customers can turn to more reliable suppliers. Finally, if Russia stops supplying gas to Europe, it will remove a key reason why the EU is hesitant to impose tougher economic sanctions on Russia. So the costs of not supplying gas are high for Gazprom. Indeed, even at the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union continued to supply gas to the West.

Given that Gazprom must continue to provide gas to other countries, EU energy firms like RWE will still receive Russian gas and, by EU rules, these firms can sell the gas they own to anybody, including Ukraine. As I indicated above, the price for Germany is about $385. But if transportation costs through Ukraine and a few other countries are excluded, the price for Ukraine could be as low as $300. So Ukraine can get around a devastating shutdown and buy gas at a cheaper price than offered by Gazprom.

Ukraine pumped 83 billion cubic meters of Russian gas to EU countries in 2013. If Gazprom declines to pay Ukraine for transportation, Ukraine may take gas from the pipeline as a payment further reducing its need of direct imports of Russian gas.

Figure 1. Gas pipelines

Third, both Ukraine and Russia have filed lawsuits with the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, which is a court in Stockholm specializing in resolving trade disputes. Interestingly, the court was set up to resolve trade disputes between the West and the USSR. Although it is hard to predict the ultimate outcome, there are good reasons to think that Ukraine is likely to prevail. For example, the prices for Ukraine were not market-based; previous contracts were signed under duress (recall cold winters when previous gas wars happened); Russia violated parts of its previous contracts with Ukraine (e.g., to transit a certain amount of natural gas every year); and the European Energy Charter prohibits any unilateral or concerted anti-competitive behavior in economic activities in the energy sector.

Previous arbitrationof disputes between Gazprom and its European customers in Poland, Germany, Austria, Czech Republic and other countries led to price reductions and elimination of costly penalty clauses in contracts with Gazprom. Obviously, court proceedings can take time but both Ukraine and Russia signed the Energy Charter which requires supplying energy while disputes are undergoing arbitration in courts. It is not clear that Russia is going to meet its legal obligations but violating the charter or the ruling of the court is likely to intensify anti-trust investigations and Gazprom may end up paying hefty fines measured in billions of dollars.

Fourth, Ukraine was the third largest European consumer of Russian gas in 2013. Losing a customer this large is likely to hurt Gazprom. While diversification of Ukraine’s sources of natural gas is limited in the short run, Ukraine can follow other European countriesand greatly limit the market power of Gazprom over the next 5 or so years by importin lgliquefied gas or using its rich deposits of shale gas. For example, an LNG terminal in Odessa can become operational within a year.

Fifth, in previous gas wars, Russia portrayedUkraine as an unreliable partner. There was a lot of pressure on Ukraine to reach a deal with Gazprom quickly. This time it is clear that Ukraine is a victim and, hence, more pressure is shifted on Russia. Ukraine has been inviting international observes to gas talks with Russia and this turned out to be helpful in identifying who does not want to negotiate in good faith. In any case, Ukraine gets a lot more help now than in the previous gas wars.

In summary, we may see a long game of attrition with an uncertain outcome. While Ukraine is an underdog in this fight, it is far from certain that Ukraine will lose. Furthermore, even if Russia wins this battle, it is going to lose the war in the long run. The three gas wars between Russia and Ukraine illustrate Russia’s willingness to use its natural resources as a geopolitical weapon, so that having European countries continue to depend on Russian gas supplies poses a significant political and economic risk for them. While these countries may be unable to substitute away from Russian gas in the immediate future, they can certainly diversify their supplies in the longer run. This path entails some short-run costs, of course, but many countriesappear to be willing to pay it to avoid Gazprom’s blackmail. As a result, Gazprom will ultimately shrink and lose its potency as a weapon.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations