Since the onset of Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, an unprecedented barrage of sanctions has sought to constrict the renegade economy, limiting its ability to trade around the world. Countless restrictions covering the country’s technology procurement efforts, oil export trade, and financial markets have formed a resounding international rebuke to unwarranted aggression. Yet, this potent package of punishments has been met with surprising economic hardiness and minimal military deterrence. While domestic pundits have hailed the strength of the rogue state’s economy, Russia’s resilience can be largely attributed to critical release valves in post-Soviet states. To better account for such discrepancies in this wartime economy – and its implications on Russia’s war in Ukraine – we must look to Central Asian states to the South of Russia.

The countries of Central Asia, namely Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan, have long enjoyed special, vestigial trade relations with Russia. Since February 2022, these growing economies have spoken out against the Russian invasion of Ukraine and adhered to Western sanctions such as those on the Russian banking system. Such behavior is in line with historical responses, with similar reactions to the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and Donbas and the 2008 Russo-Georgian war. However, due to the relatively limited scrutiny on this area’s financial dealings, Russia has turned to Central Asia as the crux of Byzantine sanction evasion networks. Year-over-year trade increases signify a robust and growing link providing alternative trading routes for Russia. This clear discontinuity between purported policy and trading records illustrates the economic reality of multipolar foreign relations in Central Asia: without Russia, prosperity is impossible.

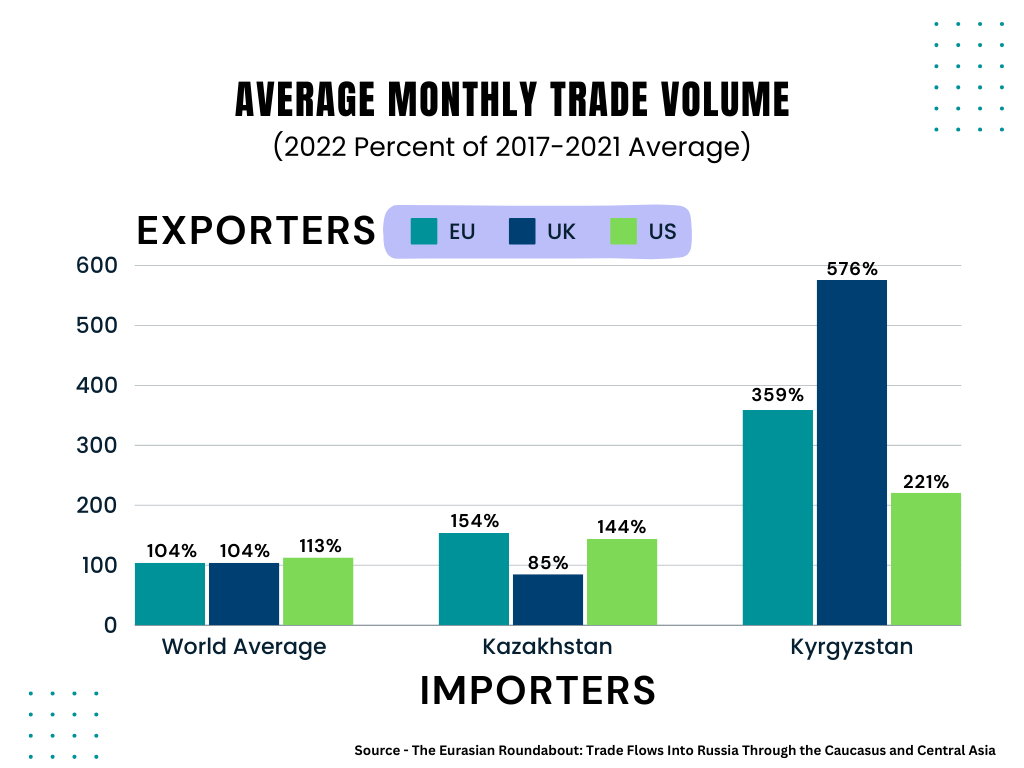

Compared to pre-war trading levels, Central Asia has significantly increased its business dealings with Russia by a non-negligible margin. In particular, Kazakhstan (by virtue of its 7644 km (4750 mile) border with Russia) and Kyrgyzstan have been the greatest benefactors of these emerging trade flows. In Kazakhstan, total export value to Russia in the past year has increased by nearly 20%; in Kyrgyzstan, it nearly tripled. These analyses already paint a stark picture of the current trading paradigm in Central Asia even while failing to account for dark markets that are obscured from public scrutiny. Moreover, it is important to consider the category of goods that are exchanging hands in these nations. Some products, such as rare earth metals and steel, have simply experienced surging demand and swelled the coffers of Central Asian industrialists. However, a suddenly growing list of exports have no industrial basis in the region and are instead imported from Europe and the United States.

This phenomenon, often referred to as “re-exporting” or “import substitution”, has formed a key pathway for Russian procurement efforts to bypass Western sanctions. Private reports from Russian procurement efforts describe machined ball bearings, maritime navigation tools, and heavy automated machinery being obtained in this fashion. These forms of parallel importing directly flaunt outstanding Western sanctions, including those targeting spare airplane parts as well as the high-purity gasses critical to chip manufacturing. Furthermore, reports of military-grade drone shipments and missile microchips crossing the border into Russia via Kazakhstan have been received with great consternation by the international community. It is without a doubt that the blame for this continued sanction failure is two-fold: Impotent regulation within Central Asian transshipment vectors and deliberately wanton ignorance in Western economies.

Against the backdrop of the ongoing invasion of Ukraine, none of the Central Asian nations have spoken out in support of Russia and all have ostensibly complied with international sanctions. However, these economies, oft-described as “maximally pragmatic”, remain reliant on Russian trade resulting in lax restrictive actions. In the past year, successive visits to the region by Western officials have gradually extracted increasingly concrete commitments with disappointingly unreliable execution. Some recent cases include Kazakh officials committing to an online tracking database and clarified inspection order and the Kyrgyz government agreeing to extended tracking and detention of several high-importance categories. Such instances of effusive support continue to be articulated across the region, but discrepancies in implementation have drawn the ire of international regulators seeking to isolate Russia’s economy.

Despite such assurances, the flow of illicit goods continues unabated to the dismay of Ukraine and its allies. In one bombshell incident, Kyrgyzstan changed its shipping categorization codes from 10 digits to 4 digits, effectively disguising unlawful trade under broad categories. Such events have resulted in American pressure on Kyrgyz companies and a spate of deterring sanctions even as the government vehemently denies its role and seeks to acquit itself. A follow-up investigation by the Kyrgyz Republic in June 2023 remains fruitless, partially due to stagnant action on offending exporters. Similarly, Kazakhstan announced “comprehensive cooperation” at a trade summit, even as illegal trade across its borders continued unimpeded. These constant pledges have been undermined by rampant unauthorized trade of key materials and must be accompanied by stemming materiel flow at its source.

Particularly in the European Union, vested interests and shadowy agendas have sought to continue their war profiteering by engaging in trade supportive of the Russian war effort. From 2021 to 2022, Kyrgyz trade in aerospace parts from Europe exploded from $0 to $3.5 million. For a country with minimal aerospace ambitions, this surging interest is clearly abnormal and should have been flagged as possible sanction evasion. Similarly, Kazakh interest in spare computer parts grew sevenfold to $1.2 billion in 2023, marking an egregious irregularity that could not escape detection by Western regulators. It is clear that illicit trade between Russia and Western economies is a substantial occurrence, particularly via third-party intermediaries such as Central Asian nations. These flagrant cases of obviously suspicious trade have yet to incur further inspection and represent a clear failing on the parts of Western governments.

If the countries of Central Asia are inextricably tied to Russia’s economy, we must better understand the basis of this relationship and explore methods of decoupling. The lingering impact of the Soviet Union continues to influence modern trade flows, underscoring the central role of Russia in connecting each Central Asian nation. However, geopolitical powerhouses in Europe and the Middle East have sought to alter this reality, extending olive branches offering support and financial cooperation. The United Arab Emirates have been a major player in this region, investing heavily into energy and mining deals while promoting regional partnership. Europe has also sought to strengthen their relationship with Central Asia, highlighting the Middle Corridor connecting Europe to China via Central Asia. Finally, the U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently visited Central Asia for the inaugural meeting of the C5 + 1 platform. Such efforts have been lauded bilaterally and mark a cursory attempt at addressing Central Asia’s reliance on Russia and opening the region to further cooperation.

Intra-regional support has also been an important factor in isolating the Russian economy by promoting Central Asia. Some governments, such as Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, have expressed increasing interest in the Organization of Turkic States to promote regional trade alliances and capital investment. Other platforms such as the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program sponsored by the Asian Development Bank have sought to improve geopolitical relations and advance further partnerships.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine continues unabated, it is more important than ever to understand the driving forces supplying the Russian war industry. The Central Asian nations, once part of the Soviet Union, present a significant and oft-overlooked supplier to Russia’s trade economy in its current state. Similar to India and other multipolar economies, we must recognize that the international community’s current inability to facilitate economic growth in this region has forced a reliance on Russia and created an untenable trade flow. And simultaneously, unbridled and unscrutinized exports pour into Central Asia from Western countries, brazenly ignoring their true destination and the role of the region in transshipment schemes. The development of these regional economies is critical in staunching Russia’s access to the fruits of globalization and merits further consideration from the citizens of our global community.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations