One can often hear that Ukraine is a “very corrupt” country. While the problem is there, we argue that the situation has improved since 2014, and on the path to EU accession Ukraine has a very good chance to greatly reduce corruption. This is a priority both for civil society and the general public.

Western observers often emphasize the issue of corruption in Ukraine. Donald Trump Jr. once called Ukraine “one of the most corrupt countries on Earth”. Sometimes Ukrainian anti-corruption NGOs as well as representatives of international organizations equated corruption as an internal threat and the external threat of Russia. But as Roman Washchuk observed in his famous lecture, if there is no Ukraine then the level of corruption will no longer matter. Certainly, if corruption in Ukraine were lower perhaps we would be more prepared for the war and would have fewer losses. However, the existential threats should be tackled first, and the existential threat for Ukraine is Russia (by the way, it is also a large source of corruption, both in Ukraine and in many other countries).

Ukraine’s allies have already started to think about the reconstruction of Ukraine (although we insist that the necessary condition for the reconstruction should be provision of a large number of weapons so that Ukraine could ensure security of its territory). During the reconstruction, the efficiency of using aid will be critical for the credibility of the program in the eyes of Ukrainians and foreign taxpayers. And thus, Ukraine’s international partners have the right to ask whether this time will be different and whether Ukraine’s institutions will also be rebuilt, along with physical infrastructure.

Let us look at the facts and try to answer these questions.

First, according to the corruption perception index, Ukraine is the most corrupt country in Europe (apart from Russia). However, one must bear in mind two factors: this index measures perception, and this can be affected, for example, by intense discussions of corruption cases in the media. In any case, Ukraine’s corruption score improved to 32 in 2021 compared to 25 in 2013 (higher score means lower corruption). Surveys of Ukrainians also show improvement of the situation: between 2013 and 2018 the share of people who said they gave bribes during the previous year fell from 27% to 22% (in 2021 it further reduced to 19%) and the share of those who can justify giving bribes under some circumstances fell from 37% to 13%. Interestingly, at the same time the share of people who believe that corruption in Ukraine increased grew from 49% to 61%, probably reflecting higher media attention to corruption. This positive dynamic with respect to corruption is encouraging.

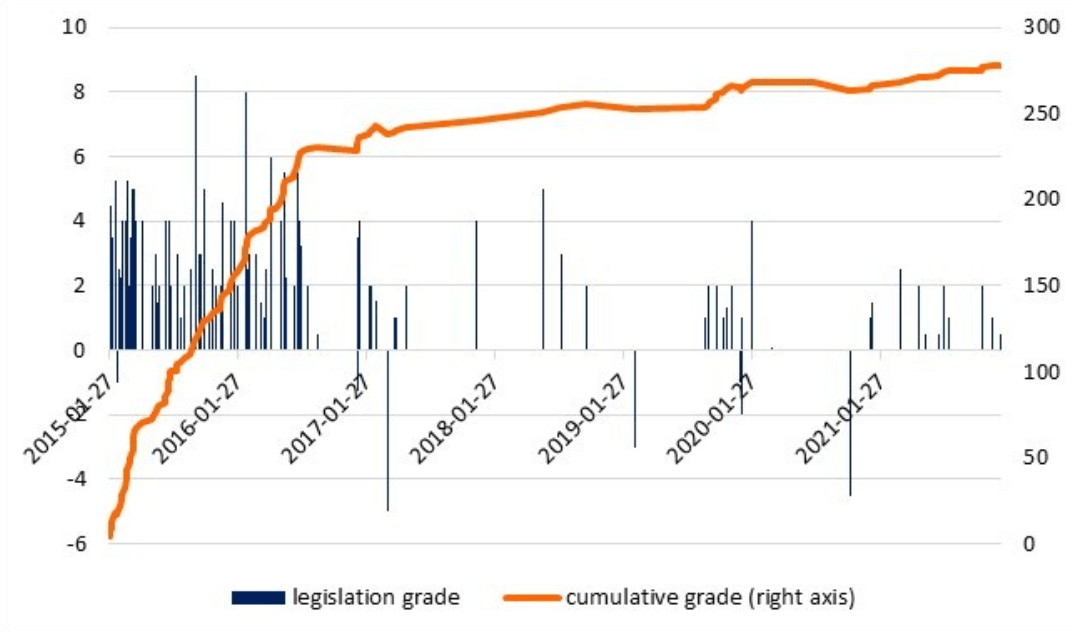

Second, Ukraine has made considerable progress in introducing anti-corruption reforms. VoxUkraine has been estimating the reforms progress in Ukraine since early 2015. Since that time we have graded almost 1300 legislative acts that change the “rules of the game”. Of these, 127 legislative acts aimed to address corruption (figure 1).

Almost a half of these legislative acts changed the rules in more than one area, and they improved governance processes to limit potential corruption. These were the laws on making data publicly available, introducing an electronic public procurement system (Prozorro allowed to save about $7 billion of public money in 5 years), transferring healthcare procurement first to international organizations and then to the specially created agency. Laws on judicial reform adopted in 2016 also received high grades. On the other hand, there were a few changes that worsened the situation with corruption. These were the introduction of e-declaration for NGOs and two decisions of the Constitution Court that (1) canceled the law on punishment for illegal enrichment and (2) canceled e-declarations. In a sign of its growing strength, civil society was able to reverse these potential retrenchments.

Figure 1. Reforms that address corruption

Source: Reform Index.

Note: reforms are estimated along 6 areas on a scale from -5 to +5. Reforms that make Ukraine more competitive and more attractive for investors get a positive grade, “antireforms” get a negative grade. A law can receive a grade of more than 5 if it considerably improves more than one of the following areas: governance, public finance, monetary policy and banking sector, business environment, energy independence, human capital.

Although not without its problems, anti-corruption infrastructure in Ukraine (Anti-Corruption Bureau, Higher Anti-Corruption Court, Corruption Prevention Agency, Asset Recovery and Management Agency, Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office) has been laid out and it is gradually changing Ukraine. Thus, during 2019-2021, NABU issued 381 indictments on high-level corruption, and 57 people were found guilty on corruption charges by the Higher Anti-Corruption Court. Nothing like this would have been possible before 2014. These policies find strong support in Ukrainian society. For example, before Russia invaded Ukraine in February this year, civil society was very active in pressuring the government to appoint a top anti-corruption prosecutor. Now civil groups are focused on the war, but after Ukraine wins (and especially if it has a roadmap for the EU accession), the internal problems will be high on the agenda again. We believe that many people in Ukraine understand that Ukraine cannot (again) lose a historical chance. We also believe that putting Ukraine on the EU accession path will be a powerful incentive to push reforms.

Third, although Russia is more corrupt (according to Transparency International) than Ukraine, it has been actively promoting the narrative about an “awfully corrupt Ukraine”, often comparing Ukraine with African countries. For example, at least since 2017 Russia has been promoting a fake about Ukraine as the most corrupt country in the world (the one repeated by Trump Jr.).

The goals of such fakes are pretty obvious. They reduce the support of Ukraine in the world, first of all among the developed countries. They also inflate the narrative of “Ukraine as a failed state” among Ukrainians and elsewhere. No wonder that Russian occupiers were surprised with the level of welfare of Ukrainians when they captured towns near Kyiv. This fake is also a justification of Russia’s aggressive war. As Koen Slootmaeckers from the University of London notes (cited in the article “How much of a problem is corruption in Ukraine?”), Russia compares Ukraine to African states to promote the narrative that if Western countries use corruption to continue subordinating African nations, then Russia also has the right to subordinate Ukraine. In fact, this is an offspring of the “failed state” narrative – stating that Ukraine is under some “external governance” (over the last years, the US, EU, IMF or Soros were interchangeably named the “external government” of Ukraine). Ironically, the heavy losses of the Russian army in Ukraine suggest that the corruption of the Russian state is ubiquitous and, if anything, it is Russia that may eventually turn out to be a failed state.

In summary, Ukraine has to do its homework to address corruption. But there are good signs. Ukraine has been gradually improving its anti-corruption infrastructure. The society demands reigning in corruption. The EU candidacy offers a powerful stimulus to fight vested interests. These forces give us confidence that Ukraine will overcome corruption as an endemic problem.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations