Recently the massive rallies of the far right parties, the powerful public presentation of the National Militia affiliated to Azov’s “National Corps” party, escalating attacks by extreme right groups against leftist, feminist, LGBT, human rights events brought Ukrainian radical nationalists back into the center of the public discussion.

The dominant narrative since Maidan in Ukrainian and much of the Western public spheres have been systematically downplaying the problem – either arguing that Ukrainian far right are not really “fascists” in the strict definition of the term, or that they are simply puppets of Ukrainian oligarchs or even Russian intelligence, or that they are small and marginal. The latter, liberal version of the denialist narrative originated during Maidan protests in politically motivated attempts to counter Russian propaganda exaggerating the far right role and to legitimate the events for the Western liberal-progressive public. Later, the poor performance of Svoboda and the Right Sector in 2014 elections gave a kind of the ultimate argument for irrelevance of the far right in Ukraine. The denialist narrative not only obfuscated the causal dynamics of toppling Viktor Yanukovych but is preventing an adequate analysis of the radical nationalists’ danger now downplaying their extraparliamentary power, violent resources, street mobilization potential, interpenetration with law enforcement and overall impact on Ukrainian politics.

In this text I am briefly summarizing my recent studies on the role of radical nationalists in the Maidan protests. It is necessary to go to the roots of the denialist myth not only for the sake of academic truth but to expose certain parameters of ideological mobilizations that are usually ignored by commenters of post-Soviet politics, although they are becoming increasingly important for analysis of the emerging trends in Ukrainian civil society.

Estimation of far right activity in Maidan protest events

It became a known fact that the polls conducted during Maidan rallies in Kiev and among the camp residents showed that members of any political party were only a small minority among Maidan protesters (not more than 15% at different stages). However, the polls during Maidan were collected only in Kiev ignoring a different reality of the Maidan mobilization in the regions. Even more important is that the data do not tell us what the specific roles of different Maidan groups in the protests were. It is a well-established fact that the broad and diverse coalitions are typical for many revolutions and crucial for their success in toppling the governments. However, the diversity does not mean equality of power within the movement or comparable impact on the success of a protest campaign. The contribution of people who only individually and accidentally joined the largest rallies is much lower than of the organized groups which were regularly and systematically involved in mobilization and coordination Maidan activities, supported the infrastructure, protected the camps, attacked the riot police, occupied the governmental buildings.

The diversity does not mean equality of power within the movement or comparable impact on the success of a protest campaign. The contribution of people who only individually and accidentally joined the largest rallies is much lower than of the organized groups which were regularly and systematically involved in mobilization and coordination Maidan activities, supported the infrastructure, protected the camps, attacked the riot police, occupied the governmental buildings.

The protest event data collected by Ukrainian Protest and Coercion Data (UPCD) team provide a unique systematic estimation of intensity of participation in protest events of various collective agents in the Maidan coalition. We created a comprehensive database of all protest, repression, and concession events in Ukraine reported by around 200 mainly local news web-media in all Ukrainian regions (oblasts) since October 2009 till December 2016. For over 60,000 events totally we systematically coded timing, location, agents, targets, tactics, issues, number of participants and other relevant variables that allowed analysis of the trends in Ukrainian protest activity for the whole period of the former president Viktor Yanukovych rule and several subsequent years. The project’s methodology was based on the well-established in social movement studies methods of protest event data collection and analysis; I described it in details in a published article on estimating far right participation in Maidan protests (Ishchenko 2016b). The data have been extensively analyzed in several other articles (Ishchenko 2018, 2016a, 2011) and cited in a number of academic publications including by prominent scholars of Ukrainian politics (Way 2015; Kudelia forthcoming; Onuch 2015; Toal 2017) as well as by journalists, human rights activists, and policy experts in Ukraine and other countries.

For the period between November 21, 2013 and February 21, 2014 UPCD team marked all protest events that were done by “Maidan activists” (or similar descriptions in the media reports) or in support of Maidan issues (for EU association, against Yanukovych, the government, the Party of Regions, against police abuse and for civil liberties etc.). Totally 3,721 Maidan protest events were coded.[1] By a protest event we mean any instance of social or political claim-making supported by empirically distinct form of physical mobilization (so, only verbal criticism is not included) outside of the central government (typical brawls in the parliament are not included) taking place on the territory of Ukraine and when at least an approximate date of the event is known. Each event was coded separately, even if it was connected to a previous event. The only exceptions were certain events that typically occured in sequence. For example, a rally that is followed by blocking a road and a fight with the law-enforcement would be coded as three separate protest events. On the other hand, a march ending with a rally would be coded as one event because it is a typical sequence. Only those events were coded which had already happened according to mass media reports; announcements for protests were not included. However, unsuccessful protest attempts which had been prevented by law-enforcement bodies were coded, while protest activities that had been cancelled by protestors because of a court order were not included into the database. A continuous multi-day event, like a strike or a tent camp, was considered a single event regardless of its duration. However, if multi-day protests had a discrete nature, for example, each evening people gathered at Maidan for a rally, each discrete rally was coded as a separate event.

Unsuccessful protest attempts which had been prevented by law-enforcement bodies were coded, while protest activities that had been cancelled by protestors because of a court order were not included into the database.

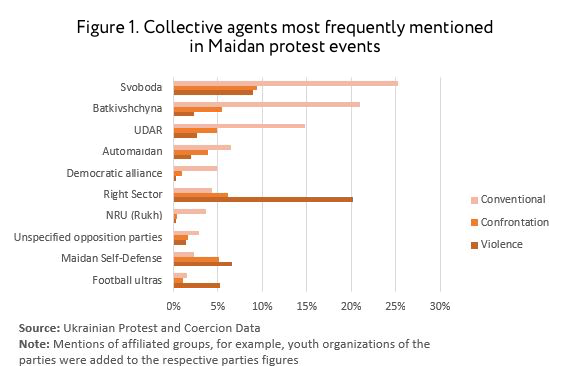

So, who were the most active collective agents in Maidan protests? In many Maidan protest events the participants were named only in a generic way, for example, “citizens”, “Maidan activists”, “protesters”, “students”, etc. However, in many other cases, media mentioned specific political parties, non-governmental organizations, informal initiatives or their members who participated in the protest. Figure 1 shows how frequently specific collective agents were mentioned in Maidan protest events of various tactics on the whole territory of Ukraine[2]. Reading the following figure, one should also keep in mind that only 14% of Maidan protest events were registered in Kiev, while almost two thirds – in western and central Ukrainian regions.

It appears that the far right Svoboda party was the most active collective agent in conventional and confrontational Maidan protest events, while the Right Sector was the most active collective agent in violent protest events. The Maidan protest events where the far right groups were mentioned were also larger (more participants reported) than the Maidan protest events where the far were not mentioned indicating that the far right were not on the periphery of the Maidan protests but in the center of the events.

As any other data, the data derived from media sources are not perfect. There are selection bias (the media report not all protest events) and description bias (events’ descriptions could be biased and incomplete). However, there are also ways to control and balance the biases, for example, by inclusion of a large number of local sources or controlling political bias by coding only the sources from specific regions (so, for example, hostile to Maidan media in Crimea did not boost the mentions of “Ukrainian fascists” participation in the events in Western regions or Kiev). The data on Maidan protest events showed also a very good consistency as Svoboda used to be the most active Ukrainian party in the protest events throughout 2010-2013 period. The methodology of data collection and the issues of potential biases are extensively discussed in (Ishchenko 2016b) where I explain why the data are very likely to reflect the actual trends in protest events participation during Maidan.[3]

Why were far right so prominent in Maidan protests?

Our protest event data, nevertheless, are limited only to the participation in strictly speaking protest events, so they do not cover important, if less visible, mobilization, coordination, media, education, and humanitarian activities of various Maidan initiatives. Moreover, we cannot tell in these data between different ways to participate in the event. To understand the impact of the far right deeper and to discover the mechanisms of the far right prominence in the protests, despite they were in minority, I turn to over 100 in-depth interviews with Maidan and Anti-Maidan protests participants (from various political parties and NGOs, elite and previously apolitical supporters) as well as with some law-enforcement officers collected by our team in 10 cities from all Ukrainian macro-regions between November 2016 and April 2017.[4]

Locations of the interviews

| Cities/Categories | Cases |

| Vinnytsia total | 3 |

| Maidan | 2 |

| Law-enforcement | 1 |

| Dnepropetrovsk total | 14 |

| Anti-Maidan | 6 |

| Maidan | 8 |

| Donetsk (interviewed in Kiev) total | 2 |

| Maidan | 2 |

| Ivano-Frankivsk total | 9 |

| Maidan | 8 |

| Law-enforcement | 1 |

| Kiev total | 13 |

| Maidan | 13 |

| Krivoi Rog total | 2 |

| Maidan | 2 |

| Lugansk (interviewed in Kiev) total | 2 |

| Maidan | 2 |

| Lviv total | 8 |

| Maidan | 8 |

| Odessa total | 13 |

| Anti-Maidan | 2 |

| Maidan | 11 |

| Rivne total | 11 |

| Maidan | 9 |

| Law-enforcement | 2 |

| Ternopil total | 9 |

| Maidan | 8 |

| Law-enforcement | 1 |

| Kharkov total | 16 |

| Anti-Maidan | 3 |

| Maidan | 9 |

| Law-enforcement | 3 (1 interviewed in Lviv) |

| Red Cross | 1 |

| Total | 102 |

Summing up the analysis,[5] Svoboda had indeed played an indispensable role in Maidan mobilization and coordination processes and this was not an accident. The party possessed a unique combination of resources among Maidan participants: ideologically committed activists, resources of a parliamentary party, and dominant positions in the local authorities in Western regions. First, unlike other major opposition parties in Ukraine (hardly more than electoral machines) Svoboda possessed thousands ideological activists organized in a nation-wide party cells network. Even if Svoboda activists were a minority among all Maidan supporters, there were still more of them than of any other single opposition party or NGO coalition. They were regularly and intensively participating in activities of Kiev Maidan camp, particularly, helping to maintain them in the periods of downturn mobilization (like in the end of December 2013 – the first half of January 2014).

Second, since 2012 Svoboda had got access to the resources of a parliamentary party. Despite the crowdfunding for the Maidan camps was of unprecedentedly large scale, it had its ebbs and flows. For example, during the periods of low mobilization, the crowdfunded money covered in some days only 10% of Kiev camp’s daily expenses. The stable cashflow from the major opposition parties was absolutely indispensable for continuous maintenance of the camps and at least in twice exceeded the amount of crowdfunded money in Kiev according to the reports during the days of Maidan. According to Ihor Kryvetskyi, the main Svoboda sponsor, who bought the main stage of Kiev Maidan camp, three major opposition parties spent approximately $6,000,000 to support the Kiev camp with Svoboda’s share of roughly 30%. Last but not least, after the local elections in 2009-2010 Svoboda had the strongest positions in the local authorities of the Western regions, where the support for the Maidan protests was the highest among the residents. This is why the party often played the leading role in the local coordination structures of Maidan and could allocate the material and symbolic resources of the local authorities to support the basic infrastructure of the protest camps, supplying the protesters with the necessary equipment, stages, food, heating, medicaments and organizing transportation to join the protesters in Kiev.

The party often played the leading role in the local coordination structures of Maidan and could allocate the material and symbolic resources of the local authorities to support the basic infrastructure of the protest camps, supplying the protesters with the necessary equipment, stages, food, heating, medicaments and organizing transportation to join the protesters in Kiev.

Overall, Svoboda made an indispensable contribution into maintaining the three months massive multiregional protest campaign, which would simply be impossible on sheer self-organization and crowdfunding without party resources. Likewise, the Right Sector’s prominence in violent Maidan events was not accidental either. One of the estimations put the Right Sector numbers in Kiev as between 300 and 500 – seemingly a small portion of the total number of 12,000 Maidan Self-Defense activists declared by the commander Andrii Parubii. However, an assumption that all Self-Defense sotnias were more or less equivalent in their role in defending Maidan camps or radicalizing the protests would be emphatically wrong. With some exceptions, like Odessa, in the most cities the major groups involved into violent and protective activities according to our informants were (from most frequently mentioned to less):

- the radical right (primarily the Right Sector);[6]

- the football ultras, who are usually tightly connected to the far right in Ukraine,

- Soviet Afghanistan war veterans.[7]

All of these were groups that had some violence training and experience unlike many Self-Defense vigilantes. The far right activists regularly trained in the boot camps (vyshkoly) and before Maidan had the largest experience in violent actions against the law-enforcement among other political or civic groups.[8] But in contrast to other “violence specialists”, as they are called in sociology of violence, the far right possessed also a revolutionary ideology and political organizations. They were actively seeking for violence and could more efficiently coordinate it on a nation-wide level. The Right Sector leaders never hid that they consciously exploited a political opportunity opened by mass mobilization against Yanukovych and escalating repressions in order to radicalize Maidan to pursue with their agenda of the “national revolution”.

Because of their active presence and contribution of crucial material and violent resources the far right had an impact on the ideological framing of the protest and were capable to mainstream the nationalist slogans and symbols among the protesters. Some local Maidan coordinators recall that Svoboda politicians were the most eager to speak at the rallies, while they needed even to solicit other politicians to come to the stage. Even when the liberal wing of Maidan criticized the use of the, they found it impossible to dissociate from the far right, even if understanding their divisive consequences for southern and eastern regions. There, according to our informants, the presence of the radical right increased the morale of the Maidan supporters that felt better protected against the violent attacks while in the same time it was alienating the skeptical majorities.

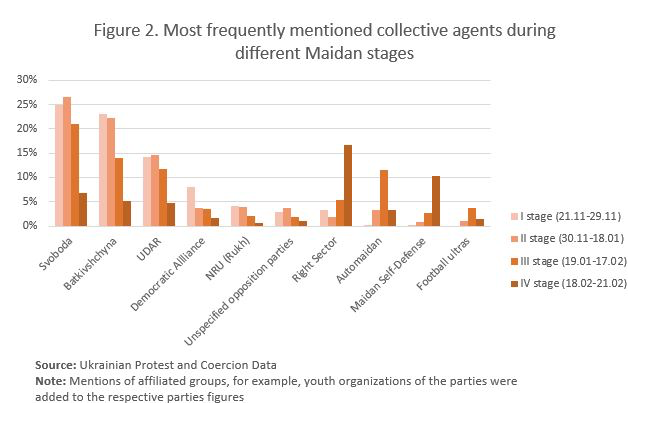

The far right were usually the vanguard of the governmental buildings occupations in Kiev on December 1, 2013 and in 10 western and central regions in January 2014. Not surprisingly that in the last days of confrontations with the government on February 18-21, 2014 the Right Sector and Svoboda played a crucial role in taking power on the local level in Western regions even before Yanukovych escaped from Kiev. Figure 2 shows how active the Right Sector became at the last, most violent stage of Maidan (February 18-21, 2014), while the prominence of most other collective agents drastically declined.

The far right were usually the vanguard of the governmental buildings occupations in Kiev on December 1, 2013 and in 10 western and central regions in January 2014. Not surprisingly that in the last days of confrontations with the government on February 18-21, 2014 the Right Sector and Svoboda played a crucial role in taking power on the local level in Western regions even before Yanukovych escaped from Kiev.

In some regional centers “the Night of Rage” happened spontaneously by loosely coordinated groups of radical right and Maidan Self-Defense like in Lviv. In other cities, like Rivne, it was a coordinated takeover of the symbolic loci of power and weapons necessary for resistance in Kiev. Already on February 19 the People’s council (Narodna rada) in Lviv uniting the opposition parties and activists claimed to seize all the power and proclaimed Svoboda-dominated local councils and their executive committees the only legitimate bodies in the region. These surprisingly understudied events in Western Ukraine were crucial for the success of Maidan as they led to a situation of “multiple sovereignty” (how it is called by Charles Tilly, the famous sociologist of contentious politics) that must have been resolved either in favor of protesters, or in favor of the government with successful counter-insurgency operation, or lead to the effective split of the country. It contributed to the law enforcement and army defection leaving Yanukovych without means to repress Maidan and protect himself in Kiev.

The Right Sector, other radical right and Maidan vigilantes helped to maintain the public order for several weeks during the power transition process. A Patriot of Ukraine activist in Ivano-Frankivs’k said that they have not even stopped patrolling the streets but only institutionalized the practice later as the Civic Corps “Azov” affiliated to the same name far right regiment of the National Guard. Here are the roots of the National Militia – the weakening of the state structures, ignorance and tolerance towards the far right during and after Maidan.

Coming back to the very typical argument in support of the denialist myth about low electoral results of the far right parties in 2014, one should note that this argument surprisingly hasa never been employed to argue about “irrelevance” of Ukrainian liberalism considering negligible support of the Democratic Alliance or People’s Power (Syla Liudei) – arguably the only more or less known parties genuinely committed to variations of liberal ideology. In contrast, the dominant oligarchic electoral machines opportunistically hijack rhetoric of both liberals and nationalists and outcompete them relying on much stronger financial and media resources. Analysis of the far right in Maidan protests turns attention to the importance of ideological extra-parliamentary politics and to the crucial role of radical minorities possessing unique activist, organizational, ideological, and violent resources that allow them to outcompete on the streets both oligarchic parties and any coalition of liberal NGOs.

Notes

[1] As a general rule we exclude from the analysis all events coded as “dubious;” i.e. where reports from different sources were too contradicting each other or where presence of social or political claims were doubtful, for example, in attacks of unknown people with unknown goals. Only 84 Maidan protest events were coded as dubious, slightly more than 2%.[2] The total numbers (100%) include all either conventional, or confrontational, or violent Maidan protest events including those events where only generic or unidentified groups were mentioned. Violent protests are protest actions causing (or threatening to cause) damage to people or property. Conventional protests refer to commonly accepted forms of protest that do not impose direct pressure on the protest targets, such as pickets, rallies, demonstrations, street performances, etc. By confrontational protests we mean actions involving direct pressure (“direct action”) to achieve the goals of a protest, such as blocking roads, strikes, hunger strikes, but not causing direct damage to people or property. Among the Maidan protest events 2,643 were conventional, 731 – confrontational, 347 – violent.

[3] One may also consult the UPCD codebook containing the complete description of data collection procedures, definitions, the list of media sources and the rules of their selection.

[4] As a part of the research project ‘Comparing protest actions in Soviet and post-Soviet spaces’, which is organized by the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen with financial support from the Volkswagen Foundation.

[5] The following is the summary of the paper presented for Danyliw research seminar on contemporary Ukraine in the University of Ottawa in November 2017.

[6] Despite frequent criticism towards indecisive leadership of Svoboda and Oleh Tyahnybok personally the informants typically made a distinction between them (“just the same” as other opposition politicos) and “rank and file” Svoboda activists who in their view contributed to the Maidan a lot. Svoboda activists were in the core of Self-Defense groups in many cities and frequently joined the Right Sector violence even against the orders of their party leaders. Svoboda leaders explained their hesitation with limitations put by their involvement into negotiations with Yanukovych government and Western politicians.

[7] There were only 19 Maidan protest events with reported participation of Afghanistan war veterans, so they are not included to the figure 1.

[8] Usually the far right were reported in 25-30% of the violent protest events per year in 2010-2013.

References

- Ishchenko, Volodymyr. 2011. ‘Fighting Fences vs Fighting Monuments: Politics of Memory and Protest Mobilization in Ukraine’. Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 19 (1–2): 369–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965156X.2011.611680.

- 2016a. ‘The Ukrainian Left during and after the Maidan Protests’. https://www.academia.edu/20445056/The_Ukrainian_Left_during_and_after_the_Maidan_Protests.

- 2016b. ‘Far Right Participation in the Ukrainian Maidan Protests: An Attempt of Systematic Estimation’. European Politics and Society 17 (4): 453–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2016.1154646.

- 2018. ‘The Ukrainian New Left and Student Protests: A Thorny Way to Hegemony’. In Radical Left Movements in Europe, edited by Magnus Wennerhag, Christian Fröhlich, and Grzegorz Piotrowski, 211–29. Routledge.

- Kudelia, Serhiy. forthcoming. ‘When Numbers Are Not Enough: The Strategic Use of Violence in Ukraine’s 2014 Revolution’. Comparative Politics.

- Onuch, Olga. 2015. ‘EuroMaidan Protests in Ukraine: Social Media Versus Social Networks’. Problems of Post-Communism 62 (4): 217–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2015.1037676.

- Toal, Gerard. 2017. Near Abroad: Putin, the West and the Contest over Ukraine and the Caucasus. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Way, Lucan. 2015. Pluralism by Default: Weak Autocrats and the Rise of Competitive Politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Main photo: depositphotos.com / palinchak

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations