Ukraine’s recovery from the consequences of Russian attacks has not stopped even for a moment. To grasp the scale of the challenge, consider this: as of spring 2025, Ukrainians had submitted over 133,000 applications for compensation for damaged housing through the eRecovery program. Already, 87,000 citizens have received payments totaling UAH 9.26 billion.

At the same time, we are rebuilding businesses, public buildings, and infrastructure. Yet all these efforts sometimes lack a systemic approach. A unified legal framework for recovery is a step we have not yet taken—and it is a critically important one. This step is essential for ensuring that the Ukrainian state, citizens, and our international partners see Ukraine’s reconstruction in the same way.

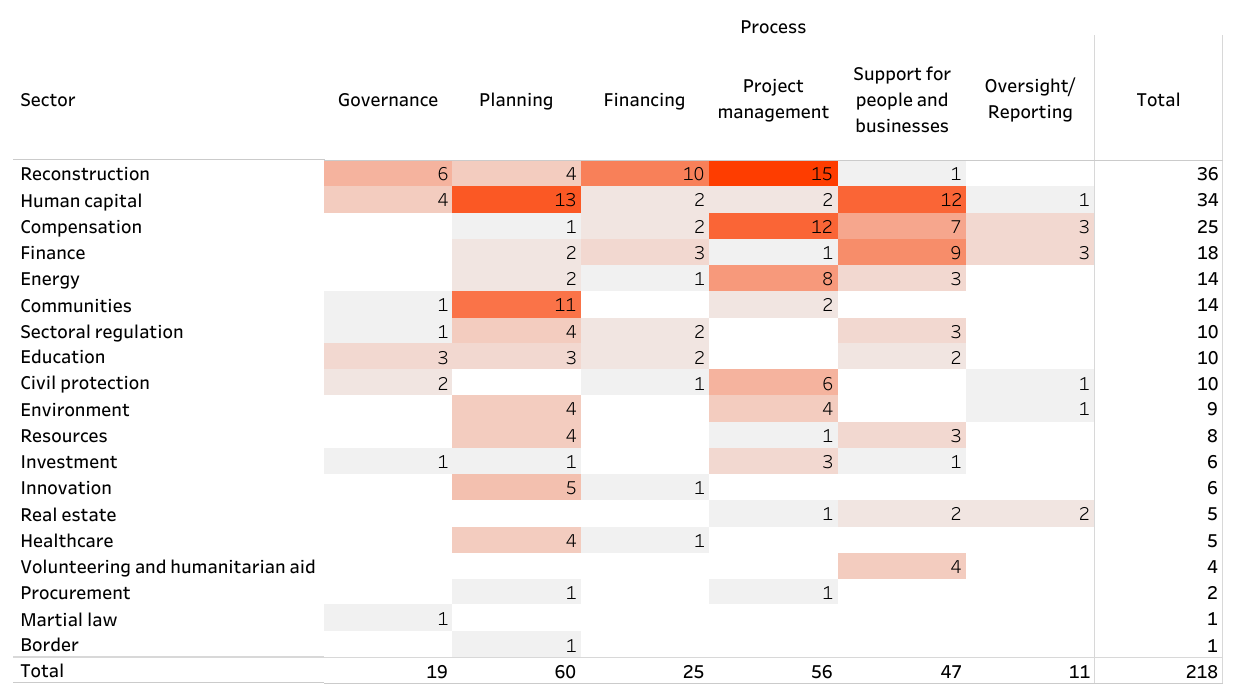

VoxUkraine team presents a new study: Recovery for All: Mapping and Analysis of Recovery-Related Regulatory Acts. The study covers the entire body of regulatory documentation created in Ukraine since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion—more than 23,000 legal acts, from which we identified 218 as most directly related to Ukraine’s recovery. A visual representation of the analysis is available on the dashboard.

This is the first study to provide a systematic assessment of a large body of legal documents—including laws, sublegal acts, and other regulations—adopted since February 2022.

Source: screenshot of one of the charts from the dashboard (the dashboard is in Ukrainian).

For 15 documents we identified as key among those available, we conducted an analysis of references to gender-inclusive approaches and developed recommendations for improving their provisions.

A broad view of recovery-related legislation revealed several gaps: inconsistencies between regulatory acts, variation in recovery-related terminology, and the absence of a single law outlining the principles of recovery that could serve as a framework for adopting other regulatory acts.

Key recommendations to address these shortcomings:

1) Adopt a unified framework law on recovery

The draft law On the Principles of Ukraine’s Recovery, developed by the Ministry for Communities and Territories Development but never submitted to Parliament, should be revised and adopted. In particular, the provisions concerning public participation in recovery should be further specified.

2) Eliminate inconsistencies between legal acts at different levels

Subordinate acts do not always align with the principles or provisions specified in higher-level regulatory acts. For example, one of the key documents guiding recovery—Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 731 on procedures for the recovery and development of regions and communities—does not require a gender analysis. Yet the Law on the Principles of State Regional Policy, which serves as the basis for the resolution, clearly states that the development of regional strategies shall be based on the assessment of the needs of stakeholders and beneficiaries in the region, and an evaluation of gender impact. This resolution should be amended to include a requirement for conducting gender analysis in territorial community development plans, as well as an analysis of accessibility.

3) Engage stakeholders in decision-making genuinely, not just formally

One year after martial law is lifted in Ukraine, the Law on Public Consultations is set to take effect. It mandates public consultations for all executive authorities and local self-government bodies, and provides for the creation of an online platform to support these processes. While the law is not yet in force, experimental projects based on its provisions could already be launched to involve Ukrainians in decision-making. These projects would make it possible to test the law’s mechanisms in practice and refine them, if needed, before the law officially comes into effect.

Unfortunately, the law does not regulate public consultations for draft laws initiated by members of Parliament. In Ukraine, such consultations are not mandatory—unlike for bills initiated by the government—so MPs make use of them only rarely. For example, in 2025, just one MP-initiated draft law—No. 12260 on credit history—was submitted for public consultations. Before that, the last time the procedure was used in 2010. As a result, Ukrainians often have limited ways to publicly express their views on regulatory acts—typically through media commentary, protests (which are prohibited during wartime), or petitions to tкуhe President requesting a veto of a particular law.

4) Standardize terminology related to Ukraine’s recovery

Ukrainian legislation contains multiple overlapping definitions of the term recovery in the context of physical destruction.

Examples include: “recovery” in Order No. 144 of the Ministry of Infrastructure dated August 6, 2022; “recovery” in Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 1483 dated December 24, 2024; “recovery of destroyed property and infrastructure” in Cabinet of Ministers Resolution No. 879 dated July 29, 2022; “recovery and/or reconstruction of real estate, buildings, and infrastructure (hereinafter—recovery and/or reconstruction of facilities)” in Order No. 65 of the Ministry of Infrastructure dated January 23, 2024; “recovery of regions and territories affected by the armed aggression against Ukraine” in the Law of Ukraine No. 156-VIII dated February 5, 2015; and “restoration work” in the Civil Protection Code of Ukraine, No. 5403-VI, dated October 2, 2012.

Each of these definitions differs slightly, making the legal framework more difficult to navigate. In our view, it would be useful to standardize the list of actions included under the definition of recovery and to clearly delineate the difference between recovery and reconstruction. If that difference is not essential and can be disregarded, a single, universal term should be adopted for such processes to make the legislation more consistent and precise.

5) Expand the use of gender legal expertise in the development of regulatory legal acts

The Law on Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men states that a conclusion from gender legal expertise is a mandatory part of the document package submitted along with a draft legal act for review. However, in practice, not all legal acts undergo such review. The procedure developed by the Cabinet of Ministers outlines two approaches: one for government documents and another for all other types. Government documents are subject to gender expertise during registration with the Ministry of Justice, while other acts—such as laws of Ukraine, presidential decrees, and so on—are reviewed only if included in the annual review plan. This plan is compiled based on submissions from government agencies, enterprises, and Ukrainian citizens. The 2025 plan includes just seven regulatory acts scheduled for gender expertise; in 2024, there were eight; in 2023, only five. By comparison, according to the Legislation of Ukraine portal, 220 laws were adopted in 2024. Clearly, the current pace of gender legal expertise is insufficient.

The full text of the study is available at the link.

This study was made possible with the support of the Government of the United Kingdom, provided through the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office as part of the project Women. Peace. Security: Acting Together, implemented by the Ukrainian Women’s Fund. The views expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of the United Kingdom, the Ukrainian Women’s Fund, or the Government Commissioner for Gender Policy.

Photo: depositphotos.com

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations