One of Ukraine’s key obligations on its path to EU membership is to significantly enhance the protection of intellectual property rights. As part of this commitment, in addition to legislative changes, the country was required to establish a specialized High Court on Intellectual Property (IP Court). Although the court was formally established back in 2017, it still has not begun operating.

What model of the IP Court currently exists in Ukraine? At what stage is its implementation? And will the IP Court fulfill its intended purpose—namely, will it be able to effectively protect intellectual property rights?

The current model of the IP Court is unlikely to achieve its intended outcomes, as the government did not follow the standard sequence for designing and implementing policies or reforms during its development (see text box).

Stages of policy development and implementation

- Problem diagnosis: What exactly is not working, and why?

- Goal setting: Why is change needed, and for whom? What outcome needs to be achieved?

- Strategy development: What models are available to achieve the goal, and which is the most effective?

- Legal framework: Creating a comprehensive and coherent regulatory base.

- Pilot implementation: Launching a test version in a specific region or sector.

- Evaluation of results: What worked and what did not? Why did it not work, and how can it be improved?

- Scaling up: Expanding the model across the entire system.

- Institutionalization: Embedding the changes in legislation, practice, and culture.

Through this article, I am publicly addressing all supporters of the current IP Court model with a series of fundamental questions regarding its substance. I urge an open and expert dialogue—one that will help uncover the strengths and risks of various models and guide us toward the most effective solution.

At a recent roundtable, the Ukrainian Bar Association (UBA) did not explore alternative models of the court, nor did the current model receive any serious or independent critical assessment. This may be because the participants supported launching the IP Court under the current model. Among them were candidates for judicial positions in the court and representatives of law firms with intellectual property practices—groups generally supportive of the current approach. As a result, participants were largely in agreement, and no substantive discussion took place.

Notably, no one raised the central question: under what specific circumstances and conditions is a separate institution like this truly necessary? After all, in many countries, intellectual property cases are not handled by standalone courts. In most EU member states—and globally—such cases are heard by specialized chambers within ordinary courts, with fully independent IP courts at the appellate level existing only in exceptional cases.

References to international experience were made selectively and one-sidedly—often in vague generalities and with elements of manipulation. Unfortunately, Ukraine still lacks a comprehensive study comparing existing models worldwide. Such a study should examine the structure of IP adjudication in selected countries, the jurisdiction and caseload of specialized courts, how responsibilities are distributed across judicial instances, the level of public trust in the judiciary, and—most importantly—whether Ukrainian conditions even remotely resemble those in countries where such courts function effectively. These nuances received no attention at the roundtable. References to “European experience” were presented as axioms requiring no justification. Yet European courts operate under entirely different conditions: with established procedures, predictable caseloads, and a high level of trust in judges and technical experts—conditions the Ukrainian judicial system currently lacks and is unlikely to attain in the near future.

Launching the IP Court in a context of war, constrained resources, economic crisis, low public trust in the judiciary, superficial accountability of court experts, and unclear jurisdiction may undermine the institution’s effectiveness.

A telling moment at the roundtable was the discussion about case volume—one of the key public arguments raised by critics of the current model, including the author (to be explored in more detail in upcoming articles). At present, there are simply not enough IP-related legal disputes in Ukraine to justify the creation of a separate IP court. For instance, China has a dedicated court due to its extensive high-tech sector, which naturally generates a high volume of intellectual property cases. Therefore, a standalone court in Ukraine—and its judges—could remain underutilized compared to general courts and non-specialized judges while still receiving the same level of remuneration.

For example, in 2023, the largest categories of cases in Ukraine involved the collection of utility debts (321,000), pension disputes (319,000), and divorce proceedings (121,000). By contrast, only 688 intellectual property cases were heard—approximately 0.02% of the total caseload. However, proponents of creating a separate court dismiss these arguments. In their view, the low number of IP cases in Ukraine is not due to a lack of demand but rather to the complexity and duration of legal proceedings, which discourage parties from going to court. It is worth noting, however, that in Ukraine’s largest regional centers, panels of specialized judges already exist, and many courts have judges who focus specifically on intellectual property matters. According to my estimates, there are between 40 and 50 judges in Ukraine who actively adjudicate IP cases—representing less than 1% of the total judiciary. If there is indeed latent demand for a dedicated IP court, it could potentially be identified through a business-sector survey—yet no such survey has been conducted.

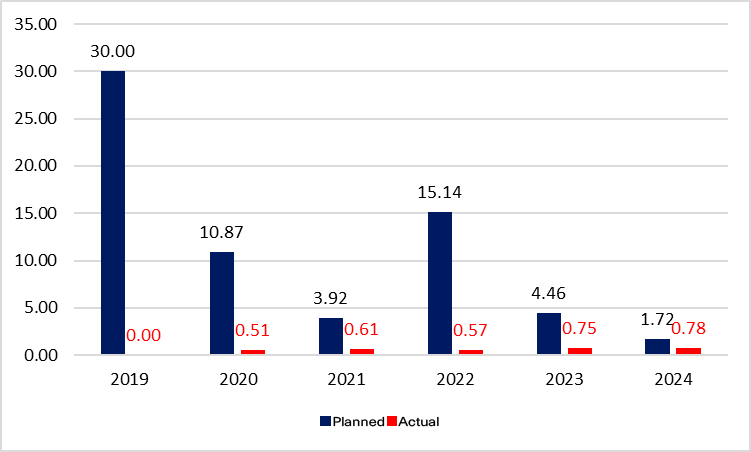

Competitions for judicial appointments to this court have been ongoing since 2017, and it has even received a certain amount of budget funding (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Funding for the High Specialized Intellectual Property Court, million UAH

Source: Treasury reports

However, since the court has yet to “take off,” perhaps it is time to reconsider the concept altogether. Ultimately, the true measure of success lies not in the establishment of a particular institution but in the ability to effectively safeguard intellectual property rights. In fact, a new court could theoretically worsen the situation rather than improve it—particularly if it lacks clear jurisdiction, judges with relevant technical expertise, or if conflicts of interest emerge among its members. Moreover, locating the court in Kyiv could limit access to justice for those in other regions. This risk is compounded by the fact that the proposed IP Court model is being actively promoted by several Kyiv-based patent law firms—some of which plan to delegate “their own” candidates to judicial positions. In contrast, patent attorneys, lawyers, and legal professionals from other cities, with whom the author has spoken, have voiced concerns about the potential creation of a local monopoly and unequal access to the court.

The most serious concern is that the professional community still lacks a clear understanding of the court’s intended place within the judicial hierarchy. According to the presidential decree establishing the court, it is intended to function as both a court of first instance and an appellate court. Yet, it is nevertheless referred to as a “High” court. Creating an institution and defining its role “on the go” is hardly a sound approach to reform—particularly in a context where every term carries significant legal, political, and institutional implications.

A judicial institution at the national level should not be treated as an experiment. It concerns the balance of rights and responsibilities, constitutional integrity, accessible justice, and the principles of stability, objectivity, fairness, and predictability. In this context, prioritizing speed over quality—or rushing to formally meet the expectations of international partners—is misguided, especially given that those partners are themselves interested in substantive, not merely symbolic, reforms.

Therefore, it is essential to critically reassess the model of IP adjudication, taking into account the actual conditions, constraints, and contextual factors present in Ukraine. Without such reflection, there is a real risk of creating a structure that will not function in practice. Developing an effective model requires confronting uncomfortable questions and comprehensively analyzing all viable alternatives for delivering IP justice.

In the upcoming articles, we will examine these questions and possible alternatives in greater detail. Specifically, we will take a closer look at the concept of establishing a patent-only court, as proposed in the 2001 presidential decree—the logic behind that reform and the attempts that have been made to implement it. We will also compare our current IP court model with international practices. In other words, we will undertake steps 1 through 3 of the reform process outlined in the text box.

Disclaimer: The editorial team at Vox Ukraine invites all interested parties to join the discussion.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations