After six years of war with Russia, it seems that Russian business has significantly reduced its presence in Ukraine. For example, driving through the streets of Kyiv, we no longer see Lukoil or TNC gas stations. Unlike Western investment, which are usually aiming for profit, Russia uses its economic presence, especially in strategic sectors of the economy, such as energy or the media, to advance its agenda and make Ukraine’s economy dependent. Such dependence can later be used by Russian officials to blackmail and promote pro-Russian geopolitical decisions.

For example, this was the case in 2010, when Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed the so-called “Kharkiv Agreements” to reduce gas prices by 30% in exchange for extending the lease of the Russian Black Sea Fleet base in Sevastopol for 25 years — until 2042. Or in 2010, when, after Ukraine’s refusal to join the Eurasian Customs Union, Russia launched a “trade war“, imposing a number of restrictions on Ukrainian goods. Or in 2013, when Russia used a number of economic levers of influence to prevent the signing of an Association Agreement with the European Union, including an additional gas discount and the $15 billion loan.

But has Russian capital really disappeared or is it simply hidding? The Centre for Economic Strategy has examined how much Russian economic presence in Ukraine has changed over the past 10 years. In the study, we also explain how to deal with the negative effects of this presence.

Officially, Russian economic presence has declined over the past 10 years, especially since 2014. Thus, the volume of Russian assets in Ukraine decreased from $20.8 billion in 2013 to $8.7 billion in 2018, the revenue of Russian companies during this time has halved to $8.8 billion, the number of Ukrainians working in Russian companies, decreased from almost 135,000 to 103,000. Trade volumes between the countries fell by 3-4 times.

However, much of Russian capital in Ukraine is hidden due to the investment through offshore or the use of fictitious beneficial owners. According to our calculations, only about half of all Russian investments in Ukraine were made directly from Russia.

In July, the Dnipro Hotel was privatized, for which the state received more than UAH 1 billion, almost 14 times more than the initial price.

But the day after the auction, the media reported that the real winner of the auction could be the VS Energy company, the ultimate owner of which is allegedly a Russian politician under European and American sanctions, Alexander Babakov. Later, the founder of the NAVI e-sports team Alexander Kokhanovskyi claimed that he and a group of the partners were the true buyers of the hotel. But the full list of investors that he has joined remains unknown.

This case highlights the problems with the transparency of ultimatebeneficiaries in Ukraine. If for a few weeks the UBOs could not be established in the largest privatization deal in recent years, it is even more difficult to understand whether the Russians are hiding behind a number of gasket companies in many other, less public, companies.

The presence of Russian companies in Ukraine can have a negative* impact on the economy as well as on politics and society. For example, Russian state-owned banks have historically issued large loans to Ukrainian state-owned companies, making them dependent on Russian money. According to our expert interviews, the subsidiaries of Russian state-owned banks had the opportunity to provide loans on better terms than other Ukrainian banks, as such loans could be subsidized by their Russian owners. The purpose of such loans could be not making a profit, but gaining access to the management of Ukrainian state-owned companies and the opportunity to influence their decisions. The data confirms that Russian loans toUkrainian state-owned companies were widespread. Thus, as of January 1, 2013, a third of Ukrzaliznytsia’s debt was owned by Russian banks. Ukrzaliznytsia is still suing over this debt, according to the latest court decision, UZ must return it.

Large industrial enterprises acquired by Russian owners often lack investmentor even are deliberately destroyed. For example, the Security Service of Ukraine and journalistic investigations suggest that RusAl company, owned by Russian businessman Oleg Deripaska, may have been involved in the destructionof the Zaporizhzhya Aluminum Plant in favor of Russian competitors.

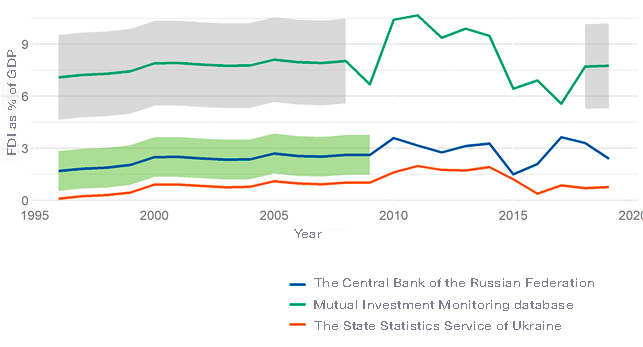

Our study shows that the level of Russian investment in Ukraine is twice as high when considering offshore investments. For example, in 2017, the total amount of Russian investment in Ukraine according to the Central Bank of the Russian Federation was 3.6% of Ukraine’s GDP, according to the Ukrainian State Statistics Service – less than 1%, and according to the Monitoring of Mutual Investments database – 5.6% (Figure 1).

Methodology

To assess the level of Russia’s economic presence in Ukraine, we considered the level of Russian investment in Ukraine, Russian-owned companies in Ukraine, and their revenue, assets, and employment in Russian companies. In addition, we analyzed bilateral trade between Russia and Ukraine.

Examining Russian economic presence in Ukraine, we looked at both official data sources, such as the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, the Unified State Register, as well asalternative data, such as the Dutch Orbis database and the Eurasian Development Bank’s Mutual Investment Monitoring Database.

To analyze Russian investment in Ukraine, we used three data sources – the Ukrainian State Statistics Service, the Russian Central Bank, and the Eurasian Development Bank’s Mutual Investment Monitoring (MIM) database. While the first two databases take into account only investments coming directly from Russia, and therefore do not take into account investments coming through offshore, the MIM database contains a list of large-scale investment projects related to Russian citizens – regardless of whether they invest directly, or through offshore.

The fact that many companies invest through offshore can be seen by looking at the list of largest countries that investin Ukraine – according to the official data, the largest investor in Ukraine is Cyprus, and even the small British Virgin Islands invest in Ukraine more than Russia.

Of course, not all offshore investments are Russian (many Ukrainian companies also invest through offshores). However, in addition to the standard reasons for using offshores (for example, tax optimization), Russian companies have other reasons to hide their true origins: evasion of sanctions, falling demand for Russian goods and services.

Figure 1. FDI from Russia (stock) as % of Ukrainian GDP

Note: In those years for which data are not available, we extrapolated the available data using the average difference between the MIMdata and the data of the State Statistics Service of Ukraine for the years for whichboth data sets are available (for those yearsthe confidence interval is shown).

Russian-owned companies in Ukraine

Using the Orbis database, we can explorethe financial indicatorsof large Russian companies in Ukraine (both those that operate openly and those that hide their presence).

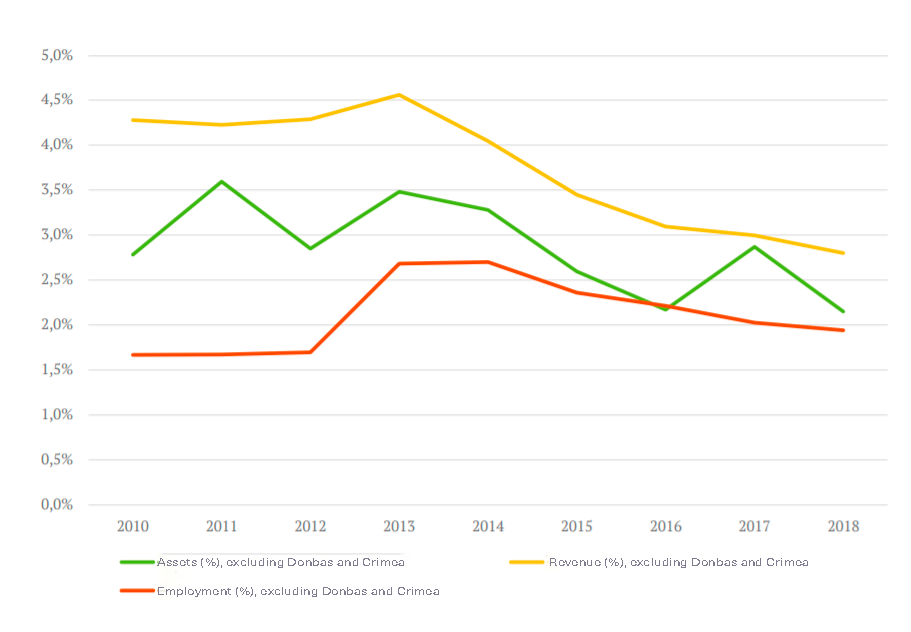

Figure 2. Financial indicators of Russian companies

Source: Center for the Study of Democracy based on the Orbis corporate database. Assets, revenue and employment are given as % of the total for all Ukrainian companies.

On one hand, we see a general trend of decreasing Russian presence: the share of assets, turnover and number of employees of Russian companies in 2018 were lower than in 2010. On the other hand, there are still a number of Russian companies left in Ukraine – in 2018, 1,553 of such companies submitted financial statements.

Their total assets amounted to $8.7 billion (2.1% of the assets of all Ukrainian companies), total revenues – $ 8.8 billion (2.8% of the revenues of all Ukrainian companies), and they hired 103 thousand employees (1.9% of all employees).

Unfortunately, we do not have data on the sectors they operate in.. However, we can look at the regional distribution. In 2018, most Russian companies were registered in Kyiv (725). However, it is possible that some of these companies only have a headquaters located in Kyiv, or they are simply registered there while their production facilities are in other regions. In second place in the number of Russian companies is Kharkiv region (104), inthird place – Odessa. On the other hand, there are less than 10 Russian companies in each of the Volyn, Ternopil, Rivne and Luhansk regions**.

To a large extent, Russia’s economic presence remains concentrated in strategic sectors of the Ukrainian economy, such as energy, telecommunications, metallurgy, etc.

Trade

Russia can exert economic pressure on Ukraine not only through enterprises or investments, but also through trade. The most apparentexample is the gas trade, when Russia forced Ukraine to make geopolitical concessions for gas discounts. However,gas is not the only example. For instance, in 2014, Russia imposed tariffs on Ukrainian products, terminated the Free Trade Agreement and banned the import of Ukrainian agricultural and food products, as well as raw materials. Earlier, after Ukraine refused to join the Eurasian Customs Union in 2011, Russia first banned the import of products from three leading cheese producers, afterward imposing a vehicle recycling fee for car exports.

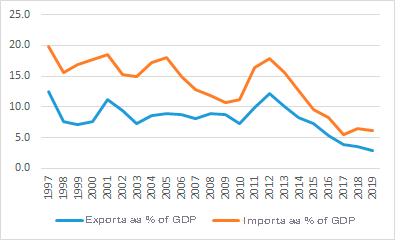

After the start of the war, the introduction of mutual trade restrictions and the suspension of direct gas imports from Russia, volume of trade with Russia decreased (Fig. 3). Last year Russia ceased to be Ukraine’s largest trading partner for the first time, giving way to China.

Figure 3. Volumes of trade between Ukraine and Russia, % of GDP

Source: The State Statistics Service of Ukraine, UNComtrade

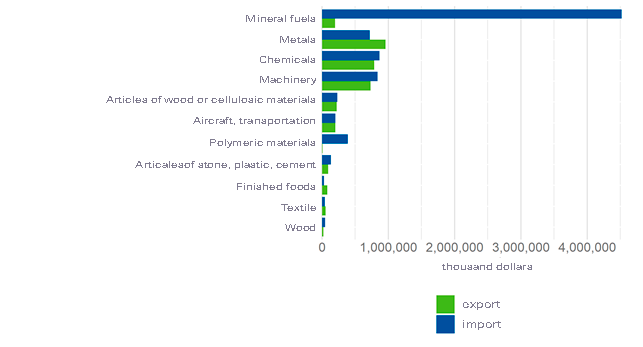

In some sectors, Ukraine cannot get rid of its dependence on trade with Russia. The main items of imports from Russia are mineral fuels and oil, and exports are metals and inorganic chemicals (Figure 4). Although trade in these goods has declined in recent years, it remains significant. The share of Russian oil in the total volume of oil purchased by Ukraine has also decreased significantly – from 50% to 32% in the period from 2009 to 2019. However, this decrease can be partly explained by the ban on oil exports from Russia to Ukraine without special permits issued by the Russian government.

Figure 4. Structure of the trade between Ukraine and Russia

Source: The State Statistics Service of Ukraine, UNComtrade

Conclusions

Russian economic presence in Ukraine has declined in all areas- investment, trade, assets and revenues of Russian companies. However, there are two important nuances.

First, about half of Russia’s investment remains “hidden”: it comes through offshore, or companies that hide the real ultimate beneficiary. is in Astudy bythe Anti-Corruption Action Center reaches a similar conclusion regarding the opacity of the final beneficiaries of many Ukrainian companies. It shows that in 2019, 27% of companies did not indicate the ultimatebeneficiary, and 1990 companies indicated a legal entity, as the beneficiary. Onone hand, 1990 companies are only about 0.1% of the total number of companies. But on the other hand, it is a direct violation of Ukrainian law, according to which companies must declare the ultimatebeneficiaries – which have to beindividuals.

Therefore, the implementation of the law should be monitored, and the penalties for failure to indicate or incorrect indication of the beneficiary should be more severe. A new money laundering law that obliges banks to verify the origin of funds in large transactions can also help determine the ultimatebeneficiary.

In this way, the state will be able to better understand the level of Russian economic presence and assess the potential danger of such presence.

Secondly, Russian economic presence remains concentrated in strategic sectors of the economy and in critical infrastructure, such as energy, metallurgy, banking, and the media. Thus, although Ukraine has stopped direct gas imports from Russia, oil trade volumes remain significant.

In the areas of critical infrastructure, just understanding who the ultimate beneficiary is, is not enough. Sometimes, in the interests of national security, it is necessary to completely prohibit the acquisition of a certain object by companies that may use it against the interests of Ukraine.

For example, in the EU, investment screening mechanism has been introduced to do this, through which investment in critical infrastructure is verified and may be banned.

In Ukraine, the Ministry of Economy has proposed a bill “On Assessing the Impact of Foreign Investment on Ukraine’s National Security,” which describes a similar mechanism. However, in our opinion, it needs to be refined: the list of sectors to be monitored needs to be expanded (adding to the telecommunications and defense sectors othercritical infrastructure sectors, such as energy and media).

The procedure by which an investment may be prohibited must be transparent, so as not to deter investments that do not pose a threat to national security.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations