As certainty is vanishing in the private sector, should governments step in? More importantly, are they able to step in and provide more certainty – to enable longer-term decisions of economic agents?

The authors are grateful to KSE professor Tymofiy Brik for his advice on the survey design

The most important characteristic of the current time is rapid and accelerating technological change. It has largely increased uncertainty. Many companies don’t know if their products will be in demand in 3-5 years or whether something completely different will catch the consumers’ attention. Creating a market rather than gaining a share of an existing market has become a new business paradigm. Increased uncertainty greatly changes business culture and processes, as well as skills companies value in workers. Thus workers also feel less secure at their workplaces.

At the same time technological change drastically reduces transaction cost – so we may actually be entering the age when Coase theorem becomes a reality, i.e. when firms are replaced by groups of people working on some projects, each of them switching to the next project when the current one has been completed. We already observe a surge in the number of freelance workers and the supporting infrastructure (e.g. employee-employer matching platforms). For workers, being a freelancer bears both benefits (flexibility) and cost (less social insurance, higher variability of income). For firms, freelance workers imply lower cost but also less leverage and thus higher uncertainty over the quality or timeliness of work. Thus technology has brought more uncertainty to the labour market.

A good illustration of a possible impact of a technologically-caused uncertainty is the 2008-2009 financial crisis. By that time financial instruments became so complicated that very few people could actually spot the underlying risks, let alone evaluate them. The CDOs and similar securities were believed to be practically risk-free until the crisis turned them into junk. As a result, in the early 2009 some banks, investment funds and individual investors were sitting on piles of money while others could not get any credit — because the lenders did not know how to tell a good borrower from a bad one. Simply put, uncertainty wiped out a large share of financial market.

Economic theory says that when the market fails, the government has to step in. And in the aftermath of 2008 crisis the governments and central banks did just that – they provided loans and purchased securities to substitute for the market. They thus supported liquidity-constrained firms and banks and helped define prices of securities. The latter task was probably more important than the first one since in the absence of a market there can be no prices. In case of share prices this implies that a “fair” value of companies can no longer be estimated. In other words, it becomes extremely uncertain – which keeps away [potential] investors.

Perhaps, uncertainty caused by technology is not specific to financial markets and can disrupt other markets too. In such cases, should the government intervene to provide more certainty? Would such intervention benefit the society?

To answer the question whether more certainty would be publicly desirable, we first looked at the available data and then implemented our own survey distributed via Facebook.

Our questions of interest were:

- do people feel the increased uncertainty and

- do they care about it (i.e. whether they would like to have more certainty).

The Institute of Sociology of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences implements a representative survey of Ukrainian society on a number of issues. In particular, it calculates the index of social anxiety. Since 1992 this index never went outside the range of 45.5 – 50.7 (on a scale from 20 to 80). In 2014 it was 49.07, very close to the 1996 value. In 2005-2012 it was slightly lower – about 45-46. More recent data are not available. Thus we can conclude that during the considered period social anxiety has been more or less stable.

When we look at another indicator which is a measure of social optimism, we see that it changes along with the economic situation (figure 1).

Figure 1. Do you think that in the nearest year our life will become more or less OK or that there will be no improvement?

Source: Social monitoring survey of NASU

Other questions allow a more detailed consideration of optimism. Respondents were asked to identify the emotions they feel when thinking about own future and Ukraine’s future. They could select several from 12 emotions: 6 positive (joy, confidence, hope, optimism, satisfaction, interest), 5 negative (hopelessness, confusion, pessimism, anxiety, fear), and indifference. To make things simpler, in the figure 2 we combine positive and negative emotions.

Figure 2. What do you feel when you think about…?

Source: Social monitoring survey of NASU

We see that people were somewhat more positive about Ukraine’s future than of their own future before 2013 while the situation reversed in 2013 (unfortunately, there is no data on the feelings of one’s own future after 2013). Generally, this measure of optimism also reflects current economic situation in the country.

We also found a reference to 2016 survey on happiness which states that 36% of people define lack of confidence in the future as a cause of their unhappiness, while 34% define poverty as this cause, and 31% could not define any cause (other answers were provided by considerably lower shares of people; respondents could select several answers).

Since the available data does not provide the answers to our questions of interest, we implemented our own survey which we disseminated through FB. We distributed the online questionnaire with a number of items about the uncertainty and attitude to it.

We received 825 responses in 7 days (Feb 26th – March 4th 2019). Our sample is not representative: 72.5% of respondents are from Kyiv. Other regions are presented more or less equally but almost 58% of respondents from them live in cities with over 500k inhabitants. Thus, rural areas are very much underrepresented (generally, about a fifth of Ukrainians live in rural areas). Gender distribution resembles that of the entire Ukraine (56% of females in our sample compared to 53.4% in the general population). People aged 23-45 constitute 73.5% of our respondents (figure 3) compared to 70.1% of Ukrainian population.

Figure 3. Age-gender distribution of the online survey respondents

Source: Own survey

59% of our respondents are employees, 22% are self-employed, 12% are students and the rest fall into unemployed, pensioners or other categories. Occupational distributions of males and females in our sample are very similar. Research shows that Ukrainian users of Internet have better financial status. Thus we expected to see a lower gender wage gap in our sample, since Facebook users are likely to have better jobs and incomes. Nevertheless, our data suggest that the wage gap is present even in this group (figure 4).

Figure 4. Distribution of respondents by monthly income

4A. Females

4B. Males

Source: own survey

65% of our respondents think that after the Euromaidan things in Ukraine have been moving in the right direction, 11.5% think the opposite and the rest are not decided. This is in sharp contrast with representative surveys which show that about 70% of Ukrainians think that things are going in the wrong direction and 18% – in the right direction. Thus our respondents are mostly supporters of the Euromaidan and subsequent reforms. Hence we would expect them to be more optimistic about the future than an average Ukrainian.

We asked the respondents what did they mostly feel when thinking about their own future and the future of Ukraine. Respondents could select one of the following emotions: fear, anxiety, non-confidence, joy, calmness, hope. They could also add their own answer. The answers they provided were: interest, responsibility, anger, sadness, fatalism, despair, and even learned helplessness. Again, we aggregated all the emotions into positive and negative. 35% of respondents feel negatively both about their own future and the future of Ukraine, 29% are positive about both. 25% feel positively about their own future and negatively about Ukraine’s future while the opposite is true for 10% of respondents. Thus there are more pessimists than optimists among our respondents, and on average they think they will be better off than Ukraine (again, this contrasts the representative sample result presented in the Figure 2).

To find out whether our respondents feel increased uncertainty, we asked three main questions:

- Are you worried more about the future than about today? (76% of respondents are)

- Do you feel more uncertainty now than 5 years ago? (37% do)

- Do you feel more uncertainty now than 10 years ago? (39% do)

We also asked a few additional questions on the subject. 49% of respondents think that their parents at their age were more confident about the future than they are now, 67% say that people in the Soviet times had more confidence in the future (however quite a few mentioned that it was because of their ignorance) while only 11% of respondents provided the same answer about 1990s.

Finally, we asked our respondents to place themselves on the imaginable “ladder” according to their confidence about the future. The distribution of the answers is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. On which level of the “confidence ladder” would you place yourself? (where 1 = people who are not at all confident about their future and 10 = people who are very confident about their future)

Source: own survey

We can infer from the above analysis that our respondents are rather confident about their future, despite being worried about it. Perhaps this is because 66% of them make savings (32% would like to make savings but can’t afford it). This only slightly differs from the general population, 43% of which do not make savings. Indeed, the regression analysis shows that people who make savings tend to be higher on the “confidence ladder”, as well as people with higher income. Those who think that Ukraine is going in the right direction and optimists also report more confidence. Occupational, sex and age variables are not significant.

The last issue we consider is whether people think that certainty is good and would like to have more of it. 57.5% of our respondents think that more uncertainty implies more risk, 37% think that it implies more opportunities, and 4% – that both. However, our respondents mostly would not agree to sacrifice their rights for more certainty (figure 6).

Figure 6. In exchange for more certainty, would you allow the government to restrict…

Source: own survey

The majority would be willing to sacrifice a part of their income to get more certainty, although not a large part – 50% of respondents could sacrifice up to 10%, another 34% could sacrifice 11% to 30% (figure 7).

Figure 7. To have more confidence in the future, I would be willing to give up the following share of my income…

Source: own survey

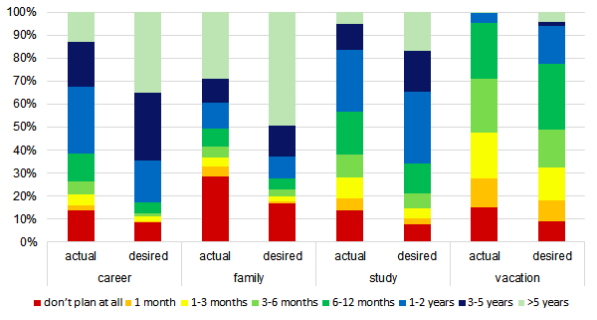

Nevertheless, the majority would like to have longer planning horizons over all areas of their life (figure 8). On average our respondents plan their career two years ahead (and wish to plan it for 4.1 years ahead), plan their studies for 1.4 years ahead (and wish to plan them for 2.6 years).

Figure 8. For which period ahead do you plan (actual) or would like to plan (desired) your…

Source: own survey

From this survey we can conclude that over 60% of our respondents (who mostly live in cities and believe that Ukraine goes in the right direction) do not think that in the last five years the uncertainty has increased. Almost 67% of them place themselves on the upper half of the “confidence ladder”. Nevertheless, 76% are worried about the future and 57% think that uncertainty implies rather risk than opportunity. A few would allow the government even partially restrict their rights in exchange for more certainty. However, only 11% would not give up any part of their income in exchange for a higher certainty. At the same time, the majority would like to have longer planning horizons than they currently do.

Our FB survey suggests that although people generally do not feel more uncertainty, they are worried about the future, would like to plan further ahead and would be willing to sacrifice some share of their income for more certainty. At the same time standard economic logic* tells us that higher certainty extends the planning horizon of business and people** and favors long-term investment.

Thus it would be useful to draft some suggestions on how governments can provide more certainty.

In response to the 2008 financial crisis they chose perhaps the easiest way – the [unlimited] provision of cash*** or promises thereof. But the Great Recession shows that providing certainty with these instruments has undesired consequences. Firstly, such QE programs are rather hard to wind down. Secondly, unlimited liquidity may have pushed the developed world into the vicious circle of low interest rates – increased savings – even lower interest rates. At the same time, in the presence of uncertainty increased savings have limited spillover into investment — when people are not sure about safety of their savings and returns on them, they tend to pile up cash or guaranteed bank deposits rather than make riskier investment such as purchase of shares.

In the world of rising uncertainty, there are a few certain things that will likely worsen the situation. Today we are observing slow but irreversible shift of economic fundamentals. These are shrinking labour force and rising dependency ratios, accelerating mobility of capital, notably human capital, and growing environmental problems, including climate change. The latter factor not only changes traditional patterns of living and [agricultural] production — it also increases the frequency and severity of natural disasters thus adding to uncertainty.

An obvious way for a government to both mitigate uncertainty and deal with the long-term challenges described above is to pursue long-term policies. A benevolent government would make long-term investment or commitments in order to raise future productivity and sustainability. For example, it could invest into education facilities and quality of teachers. Or it could secure higher tariffs for “green” energy producers for a substantial period of time. However, as we discussed in the previous article, in democratic countries governments usually pursue short-term policies aimed at [immediately] pleasing certain groups of voters and winning the next elections. Often such short-term policies have adverse long-term effects.

But probably the worst thing a government can do is a policy U-turn. One prominent example from Ukraine was cancelling of the transition to the 12-year secondary school. In 2010, eight years after the start of the transition, the parliament voted for the return to 11-year school. Students who were to graduate in two years suddenly discovered that they would have to graduate in a year. Thus they had to raise their effort (and/or the money paid to tutors) to study a two-year program in a year. This abrupt policy shift not only worsened the “starting position” of poorer students, it also raised social resentment of the idea of educational reform. The transition to the 12-year school was renewed only in 2016.

This is just one of many examples of sudden policy reversals in Ukraine. The scale of the problem is best illustrated by the fact that in our country “legislative change” is included into standard force-majeure clauses of contracts.

How one can ensure that legislative or policy changes do not become force-majeure events and at the same time respond to rapidly changing environment? The answer is simple in theory but very hard to implement in practice – robust (but not rigid) institutions. Namely, efficient and transparent decision-making processes. These processes (be it legislation development or government decisions on specific policies) should necessarily include:

- a clear formulation of a problem and its underlying causes

- consultations with stakeholders on possible ways to solve the problem

- evaluation of cost and benefits of different solutions to select the most efficient one

- a system for monitoring of implementation of that solution and evaluation of the results

In addition, all of the above should be extensively communicated to the public.

Clear and transparent processes and strong institutions provide certainty in a sense that economic players can foresee possible reaction of the government to external shocks. Providing certainty implies sticking to decision-making procedures rather than unchanged legislative provisions. Knowledge of the decision-making process would allow economic agents to rationalize their policy expectations. If in addition they can participate in drafting a policy response, they would feel even more confidence and control over the situation.

While uncertainty cannot be completely eliminated, it can be significantly reduced by strong institutions – or “rules of the game”. In a game of chess, one can only guess which piece her counterpart will move next. However, if the rules are observed, one can be sure that she will not be hit with the board. And this makes the game possible at all.

* We need to keep in mind that for a representative sample the results may be different.

** For example, when entering a university one tries to forecast which professions will be in demand in 5-10-15 years.

*** In fact, a widely discussed “universal basic income” policy is also aimed at reducing uncertainty: when people know that they receive subsistence funds unconditionally, they are more inclined to take risks and invest. However, the big question is who will pay for that.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations