This year’s laureates of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel—commonly known as the Nobel Prize in Economics—are Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt, honored “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.” In different ways, the scholars have shown that economic growth does not happen on its own—it requires continuous innovation, adaptation, and improvement. Therefore, when a society begins to stall for lack of new technologies, its economy soon drifts into stagnation.

Joel Mokyr, a professor at Northwestern University, received half of the prize for his historical research showing how scientific knowledge, practical know-how, and a society’s openness to change make continuous progress possible. The other half was awarded jointly to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for their mathematical model describing growth as a process of creative destruction, in which innovation pushes outdated products and companies out of the market.

The laureates demonstrated that economies grow not simply because people work more or produce more, but because new technologies emerge that make old processes more efficient—or replace them altogether. In the nineteenth century, people used gas lamps; today, almost every home has LED lighting, some even with a remote control. Once, accounting in enterprises was done manually in ledger books; now it is managed through automated ERP systems (enterprise resource planning). Each such transition “destroys” old businesses but at the same time creates new opportunities. This is what Joseph Schumpeter, one of the most influential economists in history, called creative destruction.

From stagnation to sustained growth: a historical shift

For most of human history, living standards changed little. Only with the Industrial Revolution, which began in the late eighteenth century in Britain, did scientific progress bring about fundamental change. The world entered an era of what has so far been an endless cycle of innovation—driving sustained economic growth.

It is important to distinguish between sustained economic growth and sustainable economic growth. The former refers to growth that continues over time—an uninterrupted expansion during a given period. The latter describes growth that can endure in the long term without exhausting resources.

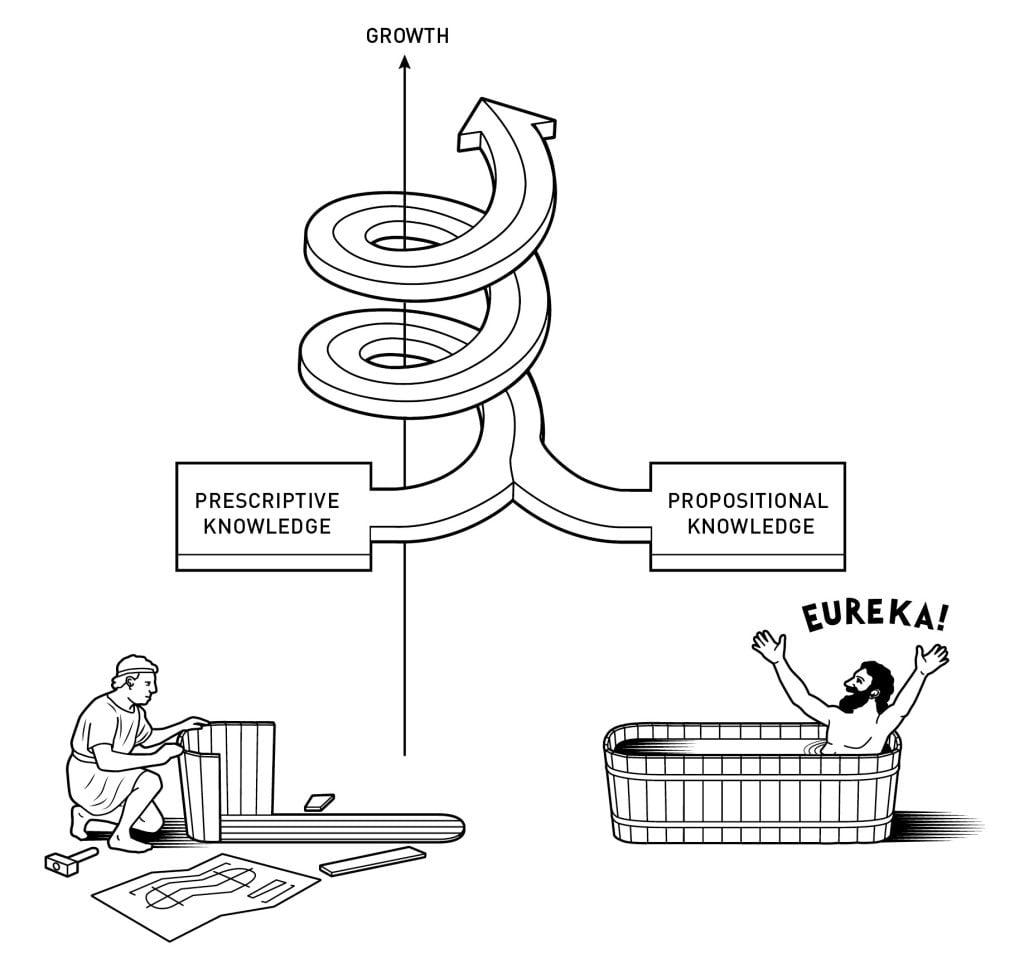

Joel Mokyr, through his study of economic history, demonstrated that growth depends on a continuous flow of useful knowledge. This knowledge consists of two parts: propositional knowledge—descriptive knowledge explaining why things work (laws, principles, theories)—and prescriptive knowledge—practical knowledge showing how to make things work (techniques, instructions).

Figure 1. The relationship between economic growth, prescriptive knowledge, and propositional knowledge

Before the Industrial Revolution, innovation was primarily based on prescriptive knowledge—people knew what worked but not why. Propositional knowledge, meanwhile, developed in isolation and therefore yielded few practical results—such as the futile attempts to build perpetual-motion machines. The Industrial Revolution began not merely with the invention of machines but with the emergence of a culture of innovation, when the focus shifted from preserving the old to pursuing the new.

Thus, technological breakthroughs become possible when a society genuinely values knowledge and science—when it turns ideas into commercial products and remains open to change.

However, there is a catch. Growth driven by technological change produces not only winners but also losers. New inventions disrupt established traditions and can provoke resistance from privileged groups whose interests come under threat.

The mathematics of creative destruction

At the heart of sustained growth lies creative destruction: a company with a better product or a more efficient method of production can push out competitors and become the market leader. This process is creative because it is driven by innovation, yet destructive because it makes older products commercially obsolete.

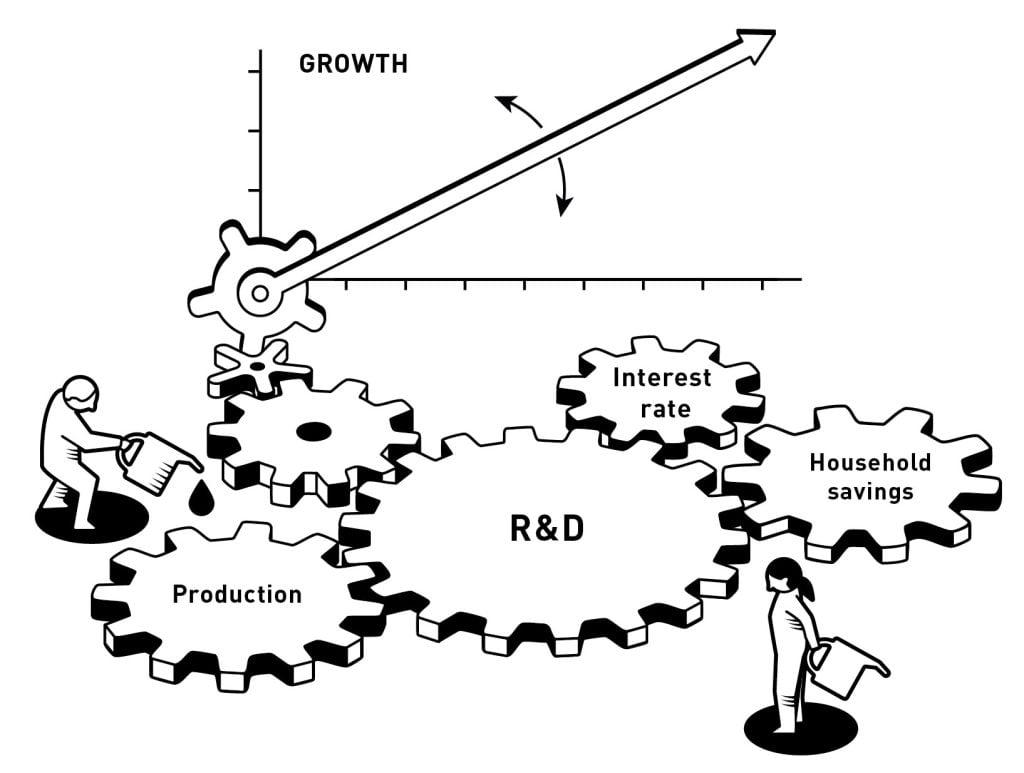

Aghion and Howitt built on Joseph Schumpeter’s idea that firms and technologies become obsolete when new and better ones emerge, and developed a mathematical model that explains when and how this occurs, as well as the conditions required for it to happen. It became the first macroeconomic model of creative destruction with general equilibrium, linking production, research and development (R&D), financial markets, and household savings influenced by interest rates.

Macroeconomic equilibrium refers to an economic model in which all markets—goods, labor, and others—are analyzed simultaneously, with supply equaling demand in each, meaning the system as a whole is in balance.

Figure 2. The Aghion–Howitt model

Its logic is as follows: companies or individuals can invest in R&D to create new or improved products or technologies. If the innovation is successful, the inventor gains a temporary advantage—a monopoly on the new technology or product—and earns higher profits because competitors do not yet have access to it. However, these advantages are temporary. Over time, others will develop even better products or technologies that displace the old ones.

As a result, for the economy to grow continuously, there must be a balance: innovators need room to strive for gains from new technologies, while established entrepreneurs must have incentives not to block newcomers—since they can preserve their position through, for example, patents, government regulation, or monopoly power.

However, there is another catch. First, long-term growth is not synonymous with sustainable growth. Innovation can have significant adverse effects—such as climate change, pollution, and growing inequality. Overcoming these challenges requires targeted policies that create conditions for encouraging innovation while simultaneously protecting those who are adversely affected in the process.

Second, growth cannot be taken for granted. The world must confront the threats that can bring creative destruction to a halt—including the dominance of individual companies, restrictions on scientific freedom, and resistance to change from groups that stand to lose.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations