How was the Ukrainian labor market operating before the Russian invasion? What has been the impact of the war on workers and firms? What can recent conflicts in Central and Eastern Europe tell us about the brain drain associated to refugees crises? Hoping that the war is over soon, what to do next?

In the book Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies (Gorodnichenko et al. 2022), we discuss these issues and provide some tentative answers.

More articles about rebuilding:

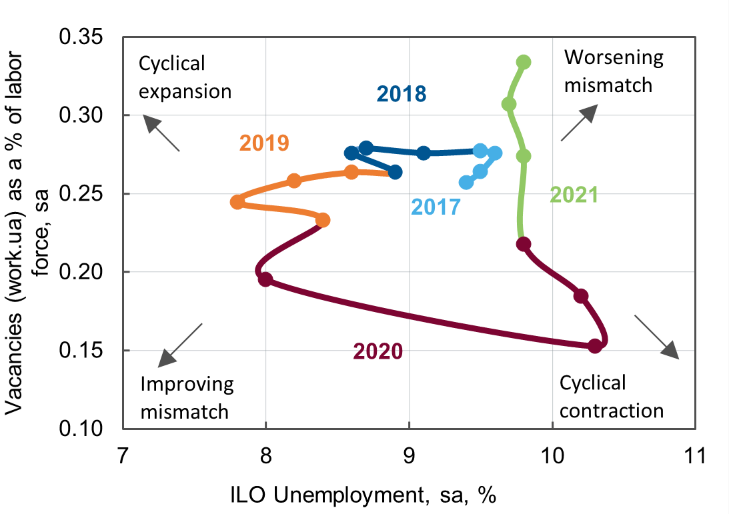

Even before the war, the Ukrainian labor market had structural weaknesses. These included a high unemployment rate (9.9 percent in 2021) and a low labor market participation (ten base points lower than the OECD average), especially for women (56 percent versus 68 percent of men in the 15-70 age group). About one sixth of employment was in agriculture, and one in five people in the informal sector. Long-term unemployment also contributed to a decline in effective labor supply: one out of four unemployed people had been on the dole for more than 12 months* and the matching of workers and vacancies was difficult inducing a shift out of the Beveridge curve (Figure 1)**.

* ILO unemployed in 2000–2021, by duration of job search.

** NBU (2022)

Figure 1

All this was occurring against a demographic background of an aging population and a low fertility rate, implying a rapidly shrinking labor force, as noted for example in Gladun (2020). In the early 2000s Ukraine had one of the world lowest fertility rates and was experiencing a sizable outmigration (Libanova, 2019).

The pandemic has only made the situation worse. The pandemic-related restrictions imposed in 2020-2021 during the pandemic on trade, transport, and services, as well as the uncertainty about over the spread of the contagion, induced strong declines not only in the demand, but also in the supply of labour. The strict quarantine restrictions had a negative impact on employment dynamics and incomes: the poverty level in Q2’2020 increased by 24.5% y-o-y (Libanova, 2021).

The Russian invasion in February 2022 disrupted the Ukrainian labor market, causing an overall shrinking of it as well as a huge mismatch – geographic and sectoral – between labor supply and demand.

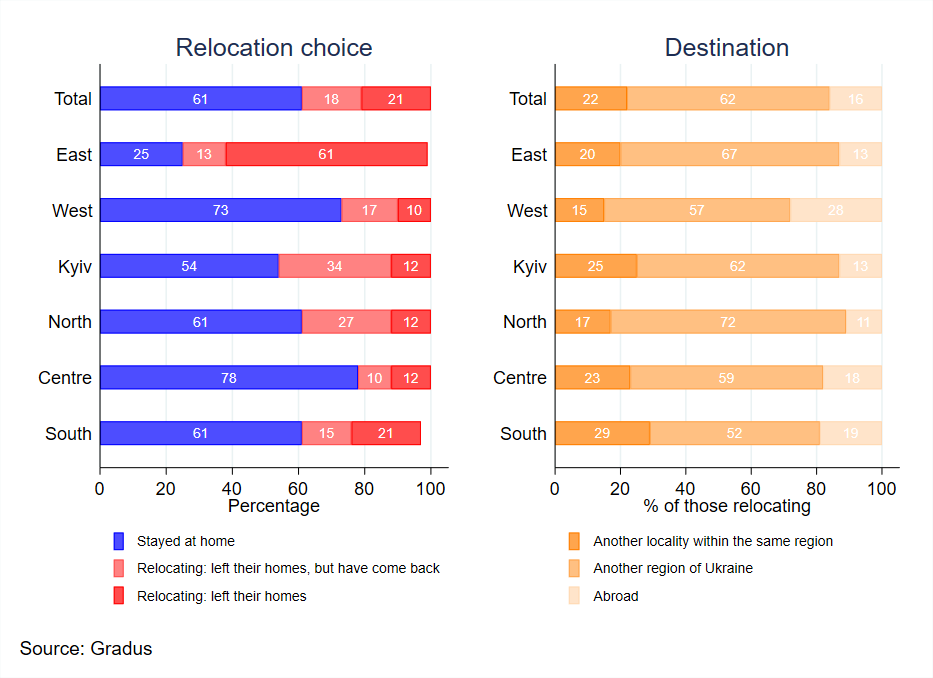

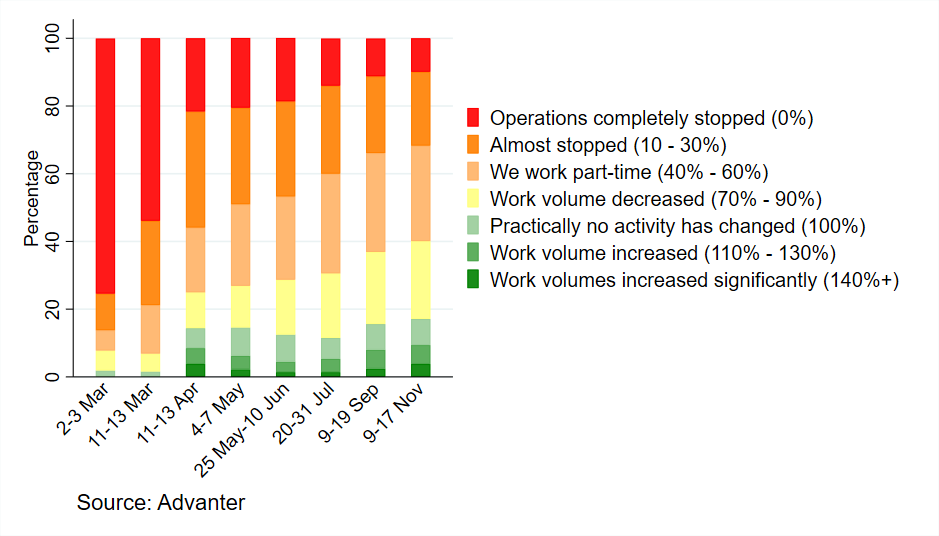

On the workers’ side, the exodus of human capital was unprecedented: the war forced more than a third of Ukrainian population (estimated in 2021 at 41 million) to move. About 5.9 million people are currently internally displaced (IOM, 2022), while more than another 7.9 million are refugees abroad: this was the largest migration crisis in Europe since World War II (UNHCR data), with women and children accounting for almost 90 percent of the refugees. Almost 5 million refugees are registered in the EU under the Temporary Protection Directive, a measure that allows them to choose their destination country and work there immediately (this allowed for a more balanced distribution of refugees, when compared to other waves – Figure 2). UNHCR (2022) Survey shows that the majority of adult refugees have a higher education (70%) and had a job before leaving (63%). A sizable share of refugees (compared with earlier conflict-caused migrations) already got a job and sent kids to schools in receiving countries.

Figure 2

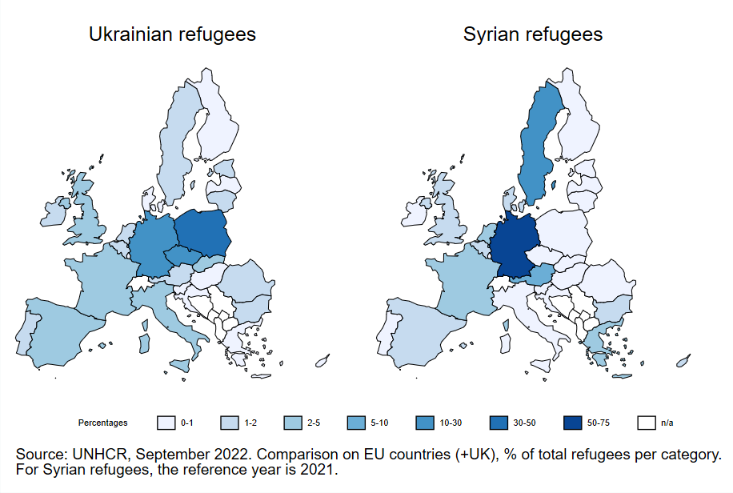

Businesses also had to move, often in a different direction than workers. Surveys of Ukrainian small and medium-sized enterprises show that, as of November 2022, about one-third of firms had completely or almost completely stopped production, while another 50 percent had reduced capacity (Figure 3). In addition to this, the indirect effects of the war must also be considered: disruption of value chains, infrastructural damage to workplaces and transportation routes, and changes in product demand.

Figure 3

The experience of Central and Eastern European countries involved in conflicts in the recent past (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo etc.) tells us that war has long-term negative effects on the health and human capital of the labor force, and that it is very difficult to reintegrate those who left to escape the conflict and decided to return after the war.

Thus, reconstruction should combine a mix of emergency measures dealing with the legacies of the war and structural reforms addressing pre-existing inefficiencies of the Ukrainian labor market. Assuming that the war is over, four main avenues of policy intervention are warranted:

1 – Investing in human capital for the future

The pandemic and the war have created huge gaps in educational attainments, as schools have been often closed, resorting at best to distance learning. Remedying to these gaps in education accumulated in the last three years should be a priority in the reconstruction of Ukraine (with programs such as tutoring, mentoring, after-school activities, summer camps etc.).

At the same time, the war destroyed millions of jobs, some of which will not come back. Therefore, crucial will be the retraining of workers, facilitating reallocation to the sectors that will likely be the most active in the post-war period (construction, engineering, health, IT).

2 – Making a better use of existing human capital

It will be important to encourage women’s participation in the labor market, supporting at the same time childbearing (i.e. strengthening the childcare infrastructure). The spread of youth unemployment can be tackled, drawing on the German tradition of tertiary education (Fachhochschule).

In addition, one of the major challenges will be how to integrate internally displaced people into local labor markets. These people have lost both physical capital and their social networks. Repeated transfers (to avoid poverty risk) and one-shot transfers (to facilitate access to credit and stimulate business restart) should be put in place, along with subsidized employment (i.e. in public works) and job search assistance programs. Often they have moved to regions that lack jobs with their specialties, so re-training programs can be very helpful.

3 – Protect the most vulnerable groups

In such a difficult environment, losing a job can have very serious consequences. That is why unemployment benefits should be reformed by expanding partial unemployment insurance: measures that allow recipients to combine benefits with low-income jobs.

War veterans could potentially be as many as a million people when the conflict ends. Evidence suggests that returning to civilian life is not easy: ad hoc measures will have to be put in place (tax credits for those who hire them, training subsidies etc). Large-scale early retirement is not feasible in light of the demographic transition. However, limited to those older workers with obsolete skills for some bridging schemes to retirement can be envisaged through an extension of unemployment benefits.

Particular attention should be given to fragile workers. The number of people physically injured by the war continues to grow, and the psychological legacies of the conflict are severe. In the reconstruction process, job opportunities and infrastructures suitable for people with disabilities, together with psychological support programs, should be provided.

4 – Promoting the return of ideas, if not people

Ukraine has suffered a major population loss, and it may not be temporary. The longer the war goes on, the greater the likelihood that refugees will remain in host countries even after the conflict is over. Nevertheless, there can be significant interactions between refugees and the labor force in Ukraine: remote working and geographic proximity (the largest share of the refugees, according to UNHCR data (1.6 million of registered for Temporary Protection) are in Poland) can alleviate the magnitude of the brain drain associated with the migration of skilled workers. The largest increase in exports from the former Yugoslavia has been registered in the sectors with the highest percentage of refugees in Germany. The pandemic has expanded remote work: this may be an additional way of bringing back to Ukraine some of the human capital lost during the conflict and not physically repatriated.

These policies should, be carried out with technical and economic support from the European Union. The process of Ukraine’s accession to the EU can stimulate, as in past EU enlargements, a major improvement in the quality of institutions in Ukraine. Some policies will also need to be financed by the EU, e.g. via the extension of the SURE (Temporary Support to Mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency) program. Progress in implementing these policies will need to be continuously monitored. Equipping Ukraine with a dynamic and modern labor market is in the interest of the entire continent.

References

Anastasia, G, T Boeri, M Kudlyak, and O Zholud (2022), “The labour market in Ukraine: Rebuild better“, in Y Gorodnichenko, I Sologoub and B Weder di Mauro (eds), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and policies, CEPR Press, London, 283-321.

Gladun (ed.) (2020), Population of Ukraine. Demographic trends in Ukraine in 2002–2019 (in Ukrainian) Населення України. Демографічні тенденції в Україні у 2002– 2019 рр.: кол. моногр. / за ред. О.М. Гладуна; НАН України, Ін-т демографії та соціальних досліджень імені М.В. Птухи. Київ: 2020.174 с. Retrieved from idss.org.ua/arhiv/population.pdf

Gorodnichenko, Y, I Sologoub and B Weder di Mauro (2022), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies, CEPR Press.

Gradus (2022), Social Screening of Ukrainian Society During the Russian Invasion – the twelfth wave of the study. Retrieved from gradus.app/documents/319/Gradus_EU_wave_12_ENG.pdf.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2022), Internal Displacement Report — General Population Survey Round 11 (25 November – 5 December 2022) Retrieved from displacement.iom.int/reports/ukraine-internal-displacement-report-general-population-survey-round-11-25-november-5

Libanova, E. (2019), Labour migration from Ukraine: key features, drivers and impact. Economics and Sociology, 12(1), 313-328. Retrieved from ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=786511

Libanova, E. (2021), COVID-19: 2020 socio-economic losses and potential risks (in Ukrainian) Лібанова, Е. М. (2021). COVID-19: соціально-економічні втрати 2020 року та потенційні ризики. Вісник Національної академії наук України, (6), 42-46. Retrieved from visnyk-nanu.org.ua/ojs/index.php/v/article/download/81/84

National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) (2022), Inflation Report. January. Labor market and household income. Retrieved from bank.gov.ua/admin_uploads/article/IR_2022-Q1_en.pdf?v=4

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2022), Lives on Hold: Intentions and Perspectives of Refugees from Ukraine #2 Retrieved from data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/95767

Authors: Giacomo Anastasia,Tito Boeri, Marianna Kudlyak and Oleksandr Zholud

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations