Ukraine is talking about pension reform again. The plan is to finally get the second mandatory accumulation system going so that employees not only “chip in on” payments to retirees, but also make sure they save for old age. Now, let us get a sense of how it will work.

The Government promises that such a system will start to be implemented by the end of 2021. Although in May 2020, Prime Minister Shmyhal said that the accumulation system could be set in motion on January 1, 2021. Before that, his predecessors had planned on launching it in 2018, with the law introducing the three-tier pension system passed back in 2003.

What is going on with the pension system now?

You and your employer pay contributions to the Pension Fund, and this money goes to the needs of those currently retired. The next generations will finance your pension. This is how the solidarity pension system works. However, this system fails when the nation is ageing, i.e. when the share of retirees is growing while the percentage of the working population is not. Currently, there are 11.3 million retirees in Ukraine. The working population is less than 16 million, of which more than 20% are working at off-the-books jobs, i.e. the Pension Fund does not receive money from them. It turns out that 11 legally employed workers provide for ten retirees. But this is not enough either – every year, more than a third of the Pension Fund’s revenues are covered by the state budget. Even though some part of this amount is payments from the state where it is the employer, the other part is still the deficit.

A survey by CASE Ukraine shows that Ukrainians are generally aware of the state of our pension system. Half of the respondents expect their retirement income to be several times lower. Two-thirds of respondents believe that the state should provide their pension. However, 26% of those hoping for a state pension would like to pay less to the Pension Fund and instead save this money on their own. The idea of a funded pension is therefore not strange to a significant number of Ukrainians.

Why does the pension system need a savings plan?

There is no magic pill to make the Ukrainian pension system sustainable and Ukrainian pensioners well-off. But it is clear that the first, solidarity-based system alone will not be able to ensure the payment of pensions for a long time.

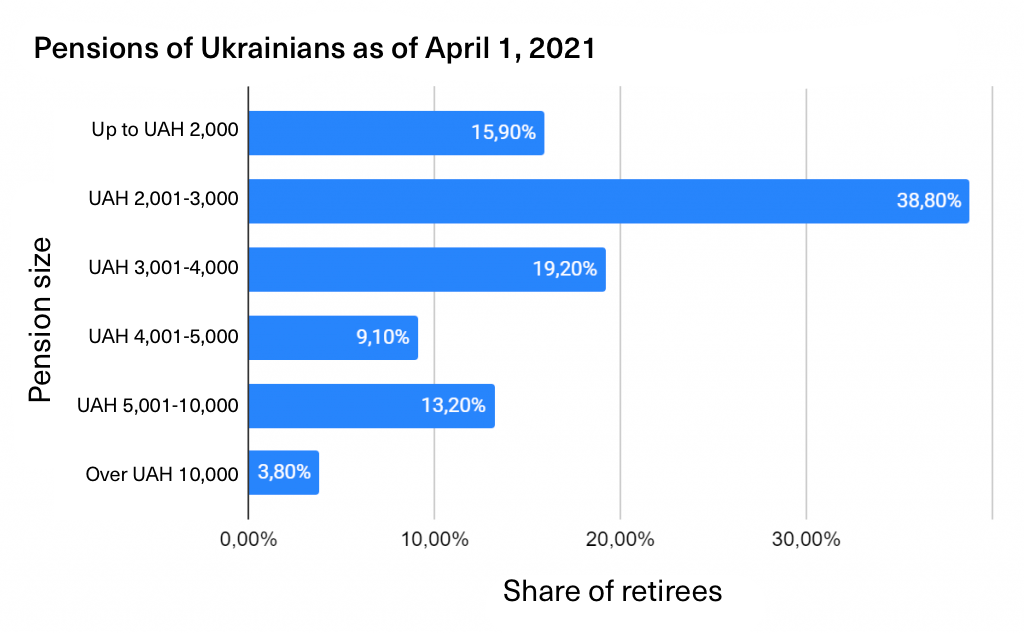

Currently, nearly 40% of Ukrainian pensioners receive from 2 to 3 thousand hryvnias. Another 16% live on less than 2 thousand, with 19% receiving their pension in the amount of 3 to 4 thousand hryvnias. According to the UN, Ukraine’s population is projected to decrease by 20% by 2050, mainly because of low fertility and youth migration levels. Hence there will be more pensioners and less young people able to earn to pay their pensions. Therefore, to keep pensions at the same level, the tax burden on Ukrainians would have to be raised.

So it seems logical to look for new ways to save for “old age”. Mandatory accumulation under the eye of the state is one of them.

According to data from the Pension Fund of Ukraine

What is being offered now?

Currently, there is no cohesive vision on how to implement the second tier of the pension system. The Government proposes to save 2% of the current USC and 2% of personal income tax. Another option was submitted to Parliament by four Servant of the People MPs. According to them, at least 3% of the current salary should go to savings, with 2% to be paid by the employer and 1% by the employee, who can also pay more if desired. The bill is already on Parliament’s agenda, passing through the committees.

But for all that, both mandatory and voluntary savings plans are limited by the level of sustainability of the Ukrainian economy, trust in government institutions, and the development of the stock market in Ukraine.

What are the risks?

The question is not only how to collect savings, but also where to invest them to at least prevent them from being eaten up by inflation. Since the stock market in Ukraine is virtually undeveloped, the choice is thin: it will be possible to invest in domestic government bonds and some corporate bonds.

The investment company ICU rather thinks that it is a plus, in the absence of very risky instruments on the market of this size. But there are downsides to it: asset managers have fewer investment tools. Adopting new stock market law will help its development, contributing to the development of both state and non-state funded pension funds. In turn, a larger amount of savings will create demand for new (for Ukraine) financial instruments.

Theoretically, long-term (pension) savings are a stable source of long-term investments. For instance, investment in production projects that take a long time to pay off. However, for this mechanism to work in practice, people need to have confidence that their retirement savings will grow, not vanish. This requires working institutions for property rights protection.

Why is it hard to get the second tier to work?

Firstly, any pension reform is unlikely to yield political dividends. According to the Reanimation Package of Reforms, changing pension systems is a serious challenge for any government since reforms affect many politically active people. Therefore, nearly all governments implementing pension reform lost the electorate’s support in the next elections. The only exception was the United Kingdom, where the government of the “Iron Lady”, Margaret Thatcher, was able to get re-elected after introducing changes to the pension system.

Secondly, introducing the mandatory accumulation system can pose a serious threat to macro-financial stability. Because if part of the funds is “transferred” from the solidarity-based system to savings accounts, pension fund deficits will have to be covered by something. If it is done at the expense of the state budget, i.e. other taxes, there will be less money left to fund other spending commitments. Doing it at the expense of borrowed funds will raise public debt, and consequently, also expenditure on its servicing.

Solidarity or accumulation?

When talking about the success of the accumulation pension system, it usually refers to the famous Chilean pension system, introduced in 1981. It relied on mandatory contributions (10% of salary) managed by private pension funds. Eventually, this model was introduced in more than 30 other countries. However, it turned out that only about 20% of the population participated in the pension system, namely those who worked officially. Most workers, especially in the informal sector, did not make pension contributions at all. And those who did so receive much lower pensions than expected. In particular, due to high inflation during the 1980s and 1990s. Therefore, in 2008, Chile introduced a solidarity-based pension system to provide for those who had not participated in the savings funds. Furthermore, due to the coronavirus crisis today, the Chilean MPs allowed citizens to withdraw up to 10% of their savings from the pension funds, threatening those funds’ stability.

At the other end of the spectrum is Georgia that abolished the pension fund in 2004 and paid pensions from the state budget. Notably, pensions were the same for all who reached retirement age (60 for women and 65 for men). However, society viewed such a model as unfair since the pension did not depend on the previous salary or length of service. Therefore, after years of discussions, a mandatory accumulation system was introduced in Georgia in 2019, in addition to the solidarity-based system.

Pension provision is probably one of the most difficult economic policy issues as it requires that forecasts be made for decades ahead. There is, however, no established algorithm or recipe here because the success of the pension system consists of many factors.

For instance, the consulting company Mercer and CFA Institute (2019) assessed the pension systems of 37 countries based on more than 40 indicators, including both the system design and general economic and demographic indicators (e.g. GDP growth and public debt). According to this assessment, the Netherlands, Denmark and Australia currently have the most successful pension systems.

According to analysts from Mercer, in order to achieve sustainability of the pension system, people need to retire at a later age, i.e. remain economically active longer. A higher level of savings is also required. For instance, besides the mandatory first and second tiers, the Netherlands have one of the highest percentages of young people in Europe making voluntary private pension savings – namely 28%.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations