In his electoral program, Zelenskyi promised to present a bill on people’s rule so that people could directly “give tasks” to the Government. On August 29 last year, the President submitted to the Verkhovna Rada a draft amendment to the Constitution proposing to give the people the right of legislative initiative. And Deputy Speaker of the Parliament, Ruslan Stefanchuk, named “people’s” legislative initiative and electronic petitions among the main tools for the development of people’s rule. The people do not have a legislative initiative yet, but they do have electronic petitions. How do they work (if at all) and how do the government bodies respond to them?

Main conclusions:

- Most petitions — nearly 49 thousand or 92% of the total — are addressed to the President, with a much lesser number being addressed to the Parliament and the Government — 2,093 and 2,208, respectively. The President is often petitioned for matters beyond his authority. Apparently, there is still a strong belief among Ukrainians in a “good tsar”.

- Most petitions were addressed to the President and Parliament in the e-petitions’ first weeks. Eventually, their numbers decreased significantly. At the beginning of Zelenskyi’s term, there was a surge in petitions, but a few weeks into his work, their numbers decreased, although they remain higher than in Poroshenko’s last years. Maybe Ukrainians believed that appealing directly to the new president would help them solve their problems.

- Part of the petitions are a reaction to current events, e.g. the coronavirus outbreak.

- A small share of petitions got the necessary votes, namely 86 out of 52,940 (or 0.16%). 27% of these petitions can be considered fully granted by the authorities, 22% were not supported, and 47% contained a note requesting other government bodies to look into the issue or set up a working group.

In 2015, it became possible in Ukraine to sign electronic petitions addressed to the Parliament and the President, and in 2016 — to the Government. To make sure that a petition is most certainly considered (with the exceptions we write about below), it needs to collect a minimum of 25,000 votes in three months.

We gathered data from the e-petition sites addressed to the Parliament, the President and the Government as of April 3, 2020 (for the array of petitions, please write to: [email protected]).

By petitions we mean the data from the three websites, unless otherwise indicated.

To classify the petitions’ topics, we used the classification from the relevant sites.

With regard to topic distributions among the petitions that received the required votes, we assigned the topics ourselves (for the accuracy of distribution) if petitions had “no topic”. The petitions that had topics were also reviewed and, where necessary, those topics were supplemented (while retaining the original topics). For the overall distribution of petitions, we automatically classified the “no-topic” petitions using an SVM trained model for the petitions with topics (the model’s accuracy is about 90%).

Since the websites’ inception, nearly 53,000 petitions have been sent to the President (it should be noted that many of the requests are not within the President’s power). So much fewer — 2,208 and 2,093 — were addressed to the Cabinet of Ministers and the Verkhovna Rada, respectively. Together, the petitions collected about 12.5 million votes.

When submitting a petition, its author may select one or more of the suggested topics. We compiled the topics from the three websites together into one dataset (for the table of correspondence, follow the link). One petition can embrace several topics.

However, in case of no default topic selected on the website of petitions addressed to the President, most frequently the petitions were classified as “no topic”. There are 37,000 of them. We classified those petitions in an automated way.

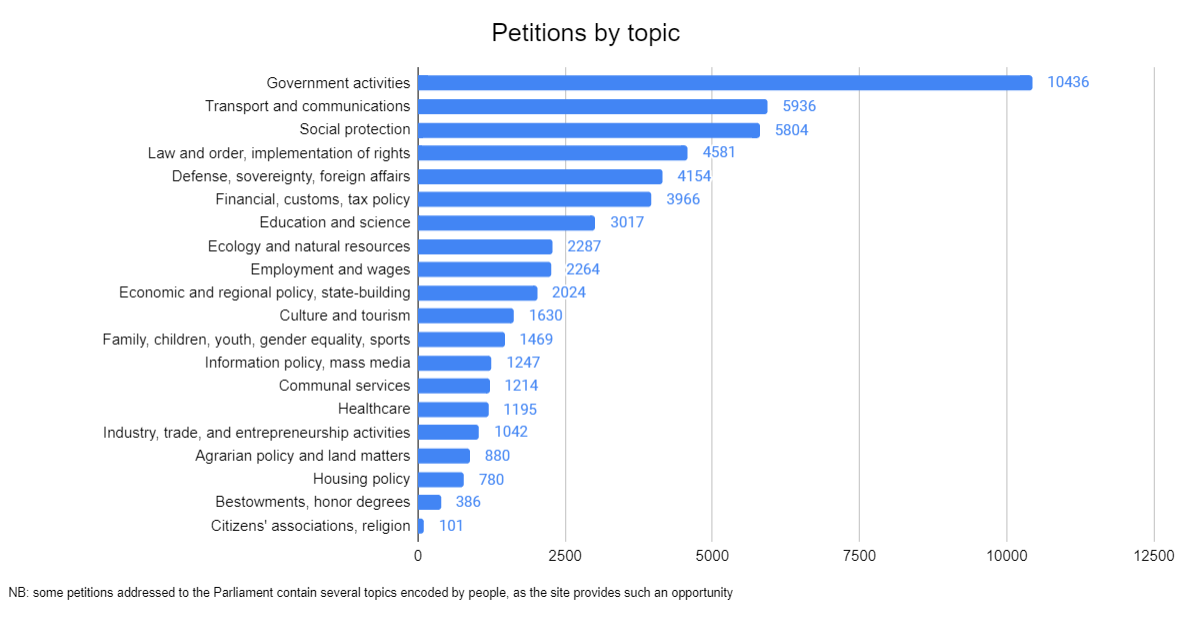

Most people concern themselves with government activities, followed by transport and communications, and social protection (Fig. 1). The smallest number of petitions related to the activities of public associations.

Fig. 1 Petitions by topic

Source: the petition sites, our own calculations

How often are the petitions submitted?

Fig. 2 Petition timeline

Source: the petition sites, our own calculations

Note: each item is the petitions’ weekly number; date tags mark the beginning of each week (except for the first tag marking the beginning of the general timeline)

Following the opportunity to send e-petitions to the President and to the Parliament, there was a big surge in petitions, e.g. on September 7, 2015. There were almost 900 of them. 17.9% of all petitions were sent in September of that year, and 7.7% in October. Their topics varied, so it is impossible to single out one main topic. However, the following month, there was a significant drop in the petitions’ popularity.

Another surge, 173 petitions, occurred on August 29, 2016. But we did not find any central event that the petitions revolved around.

A small and almost stable number of petitions was observed until the beginning of Zelenskyi’s presidency. During that period, an average of 16 petitions were sent daily (with a standard deviation of 15 and linear deviation of 11).

Another big surge in the number of petitions was seen at the beginning of the sixth President’s term. Most likely, people hoped to be heard after the change of president. No principal topic was identified for those petitions either.

By the beginning of 2020, there was a drop in the number of petitions, but in late January – early February, another small surge occurred. Most frequently, the petitions raised the “eternal” questions of abolishing or reducing taxes, utility or gas prices. Some related to the events happening at the time, such as labor laws or the land market. Yet, the vast majority did not relate to any events.

However, there was a surge of petitions relating to one central event — the coronavirus outbreak. It was observed from 10 to 31 March. Read a detailed analysis on “coronavirus” petitions in the VoxUkraine’s FB post (almost half of the 260 petitions related to quarantine).

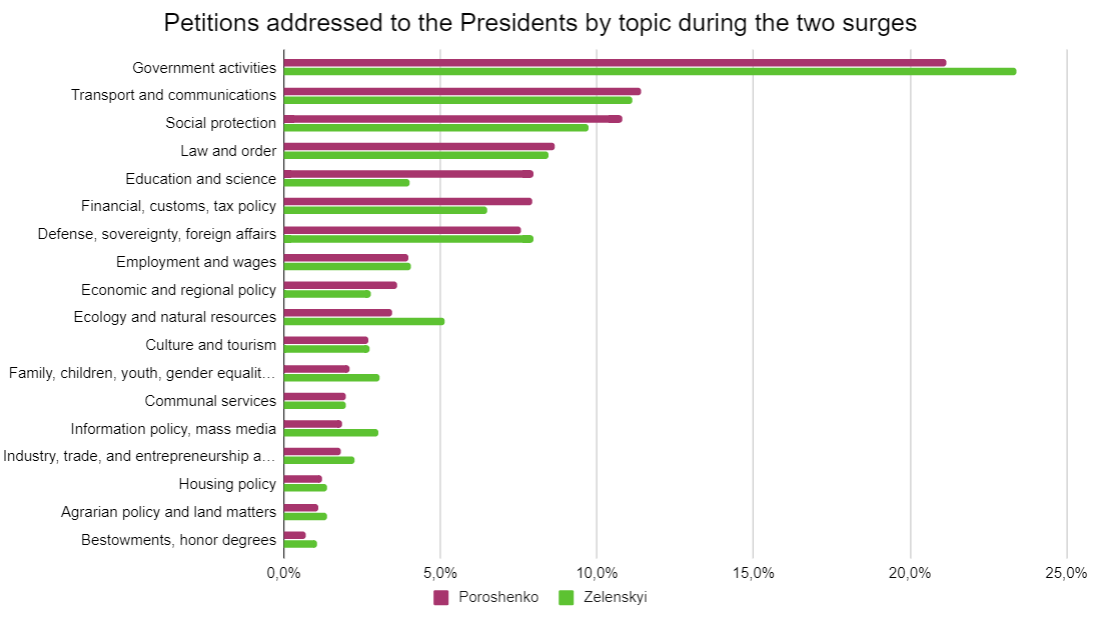

Figure 3 shows the distribution of petitions addressed to the Presidents by topic during the two major surges – at the inception of e-petitions and at the beginning of Zelenskyi’s term. The three most common topics in both periods are government activities, transport and communications, and social protection.

Fig. 3 Petitions to both Presidents during the two big surges

Source: the petition websites, our own calculations (the “peak” time for Poroshenko is 29.08-02.11.2015, and that for Zelenskyi is 20.05-27.06.2019)

As regards the topic of most concern for people during Poroshenko’s term (government activities), much attention was paid to the electoral process (restricting the right to vote on certain grounds, returning the “against-all” option, electronic voting, etc.). Lots of petitions had to do with petitions themselves: obliging the President to support the majority of petitions, merging similar ones, and improving the website (in this regard, one author even wrote his cri de coeur in the title).

Among the peak petitions addressed to Zelenskyi, the ones demanding his resignation and the opposing petitions in support of him or the cancellation of resignation-related petitions stood out. The current President was relatively frequently asked to appoint or dismiss certain individuals, as well as unblock Russian websites. Both during the first and the second “surges”, many petitions related to the Parliament’s work, with proposals to reduce the number of MPs, limit the number of parliamentary terms, vote by fingerprint, etc. Another “eternal” topic is the politicians’ responsibility to keep their promises.

As a rule, at least several petitions related to a significant event (e.g. the coronavirus outbreak or a meeting of the Trilateral Contact Group in Minsk). However, petitions relating to events were in the minority. Most were the “long-play” petitions.

Petitions that received the necessary votes and responses to them

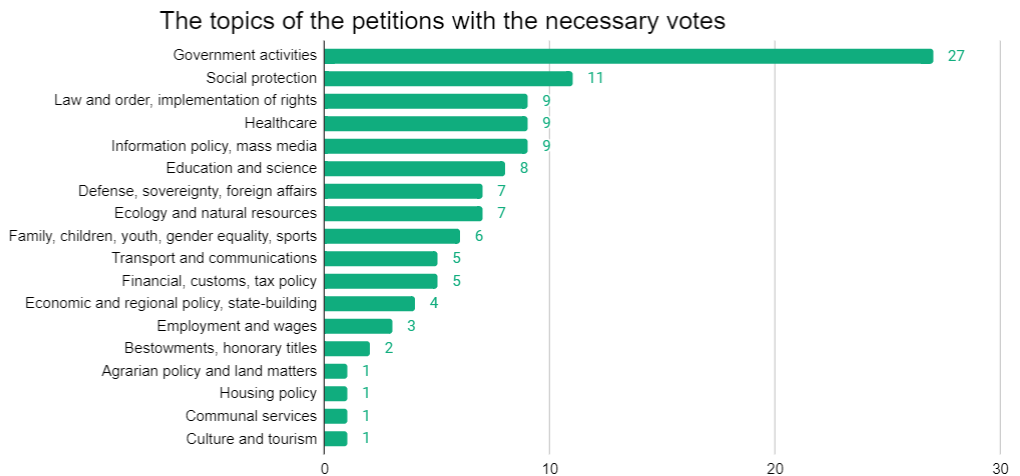

Since the inception of e-petitions, only 86 of them received the required number of votes (25,000). The distribution by topic looks as follows:

Fig. 4 the e-petitions’ topics that collected over 25 thousand votes

Source: the petition websites, our own calculations

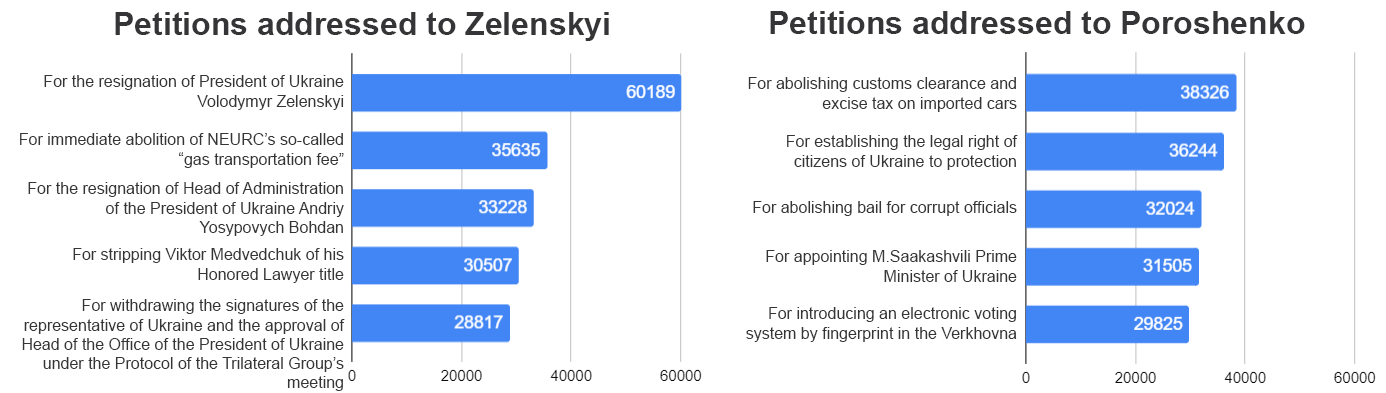

The petition for Zelenskyi’s resignation received the most votes — 60,189. The petition to abolish customs clearance and vehicle excise duties is second with 38,326 votes.

A petition receiving 25,000 votes closes a few days later and cannot be voted for any more. Therefore, the number of votes reflects the number of people who managed to vote for it before closing.

The top 5 petitions in terms of the number of votes for Zelenskyi and Poroshenko look as follows:

Fig. 5 top petitions by votes, addressed to the two Presidents

Source: the petition sites, our own calculations

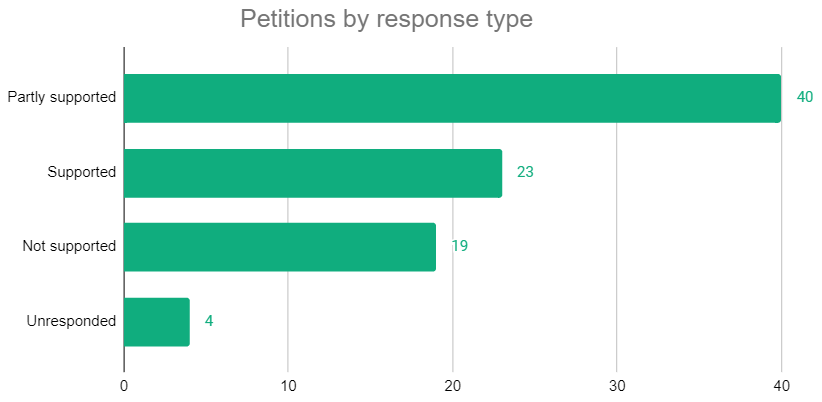

The majority of petitions (40) were partly supported, with 23 being fully supported and 19 not supported (Fig. 6). Four petitions have gone unresponded to. Three of them were addressed to Poroshenko in 2015 and 2018, and the fourth, a message of thanks to Poroshenko, was submitted in May 2019 during his presidency and received the votes after Zelenskyi became President. But he did not respond to it.

See the category descriptions at the end of this article.

Fig.6 Categories of petition responses

Source: our own calculations

Most petitions that received over 25 thousand votes related to protecting traditional values – 6 petitions (with nearly identical content, signed on the websites of all government bodies). The next three most popular topics had three petitions each (car taxation, vocational training and reducing the use of plastic bags).

A kind of battle occurred between the petitions: one contained a demand that President Zelenskyi resign, and the petition in reply demanded that the previous one be canceled (both petitions were filed in May 2019). The President thanked the authors of the second petition and called the first “trolling.”

Another “battle” of petitions took place in September-October 2018. The Verkhovna Rada received a petition to revoke the licenses of 112 and NewsOne TV channels (supported by the Committee), and shortly afterwards, the President received a petition to not impose sanctions on these channels, which went unanswered.

The Parliament also responds to petitions that did not receive 25,000 votes, but due to their large number (1943 responses), they were not part of our analysis.

In this article, we did not evaluate the petitions’ substance. We only analyzed whether they were supported or not. In our opinion, by no means all of the petitions receiving more than 25,000 votes should be supported.

And as an extra tidbit

Petitions have also long been a playground for memes and trolling, so whenever you get bored, you can come and read them.

In our opinion, here are a couple interesting ones:

Description of petition response categories

- Supported: supporting the ideas expressed in a petition (or implementing something of equal value, as the response to the request to honor Andriy Kuzmenko with the People’s Artist title) or entrusting the matter to other government bodies. “Supported” in response to a petition addressed to the Parliament means that the ideas were supported by a parliamentary committee or the Parliament as a whole.

- Partly supported: forwarding a request to other government bodies or creating a working group to consider a petition.

- Not supported: expressing no support to the ideas expressed in a petition.

- Unresponded: providing no response whatsoever to a petition that collected the required number of votes.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations