The crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic is already being called the worst since the Great Depression. These global changes affect each one of us – someone loses their job or savings, dream vacation or opportunity to study abroad, someone loses their loved ones, and someone their hope. But thinking of the Old Testament story of King Solomon, we can say: “Everything passes. This too shall pass.” Let us take a look at how people were coping with the environmental, political and economic crisis nearly 100 years ago, using the example of Dorothea Lange’s outstanding documentary photographs.

Understanding the present through the past. Photographic image as a historical document

A show of works by Dorothea Lange, one of America’s most famous photographers of the 20th century, is currently available online at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It is called Words & Pictures. For the first time in fifty years, both the most prominent photographs of the Great Depression as well as lesser-known photographs are exhibited in one place accompanied by comments from the contemporary writers, artists, and scholars. The show gives you the opportunity to experience an era that is now closer to ours than ever before. As the curator of the show, Sarah Meister, put it: “the time when Lange worked was one of extraordinary challenge and deprivation and injustice and suffering, we, every day, think about what her work brings to our current thinking of the world.”

According to her, for Lange, a camera was a tool for learning how to see without a camera. This would be one description of Lange’s artistic method, thanks to which her images came to personify the Great Depression for the whole world preserving this experience for future generations. We believe her and her photos.

The degree of authenticity embedded in a photographic image can give it a special value as evidence or proof. In her essay On Photography Susan Sontag begins by comparing literary works to paintings and drawings, arguing that depicting the world is like furnishing visual evidence of that world – thus the artist interprets certain phenomena. In contrast, “photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.” That is, a pervasive feature of a photograph distinguishing it from other types of imitation is an unquestionable belief that the “thing” was really there at a particular time, in a particular place and manner. Roland Barthes in his essay Camera Lucida calls it noeme of Photography – “That-has-been”. Sontag also writes that all photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Everything that is photographed is already part of the past, but such a part that has been recorded and can be useful someday. Sontag writes that these records of the past “furnish evidence… incriminate… pass for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.”

Convincing, incriminating, and reliable – these qualities of documentary photography can explain its powerful influence. Along with Lange’s photographs, other world-famous photographs are worth being mentioned: Buddhist monk setting himself ablaze in Saigon in 1963, Unknown rebel standing before a line of tanks on Tiananmen in June 1989, Raising a vistory flag over the Reichstag in 1945, Napalm in Vietnam in 1973, Normany landings of the Allied Forces in 1944, etc.

There is a lot to be said about constructing photographic images and using them as a means of propaganda, as ultimately happened with Evgeni Khaldei’s photograph of the victory flag, but that is a topic for another article. In this piece, we would like to focus on how the people in Lange’s photographs live, suffer and do not lose hope bringing us closer to understanding and accepting global and personal changes.

The highway going West. U.S. 80 near Lordsburg, New Mexico, 1938 Library of Congress

The Grapes of Wrath. America in the time of the Great Depression

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression in America, there was also a period of severe dust storms known as the Dust Bowl. The ecological catastrophe was provoked by drought and decades-long extensive deep plowing on the Great Plains (a broad expanse of flat land in the United States and Canada east of the Rocky Mountains). Strong winds lifted the topsoil into the air causing blizzards of black suffocating dust that completely destroyed farms and crops. The worst affected areas were Texas, Oklahoma, Colorado and New Mexico.

Dust storm near Mills, New Mexico, 1935 Library of Congress

Dust Bowl farm. Coldwater District, near Dalhart, Texas. This farm is occupied. Others in this area have been abandoned. 1938 Library of Congress

Hundreds of thousands of families had to abandon their homes moving from one place to another as the economic crisis left them no chance to find a steady job. Temporary work, e.g. harvesting crops, was generally poorly paid and workers had to spend the night in tents near irrigation channels.

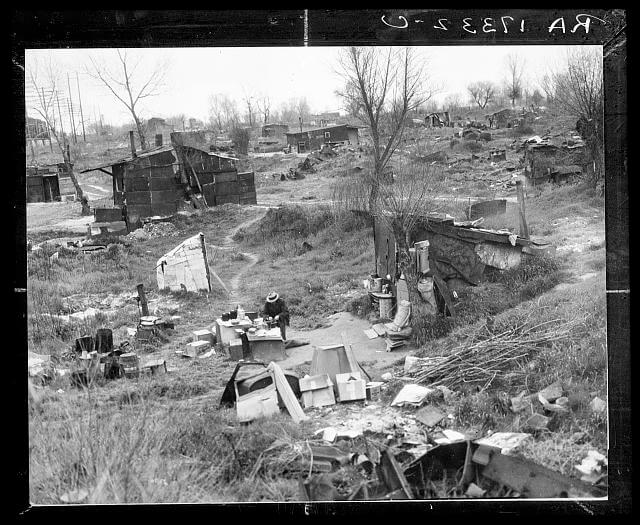

Migrant workers’ camp, outskirts of Marysville, California. The new migratory camps now being built by the Resettlement Administration will remove people from unsatisfactory living conditions such as these and substitute at least the minimum of comfort and sanitation. 1935 Library of Congress

Dust storms were not the only cause of migration. Even in good times the lives of workers were hard. In order not to pay rent in cash that was always scarce, the farmers instead cultivated the fields owned by large landowners. The Great Depression exacerbated their plight. For instance, the government gave farmers extra money for reducing production to prevent lower crop prices. However, amid rising competition from mechanized teams, able to cultivate more land in less time, the government money did not help them very much, with the large landowners evicting tenants en masse.

Four families, three of them related with fifteen children, from the Dust Bowl in Texas in an overnight roadside camp near Calipatria, California. 1937 Library of Congress

The migrant problem was going into overdrive, and as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Resettlement Administration (RA) was established in 1935 headed by Rexford Tugwell, Undersecretary of the United States Department of Agriculture and Professor of Economics at Columbia University.

The Administration relocated farmers to more fertile lands, encouraged the introduction of land conservation technologies, and provided loans. Experimental rural communities and sanitation camps for migrant workers were also constructed.

Heads of families on the Mineral King cooperative farm. Ten families are now established on this 500 acre ranch to be operated as a unit. (Farm Security Administration) Tulare County, California. 1938 Library of Congress

Tugwell created a history unit for the RA with the ambitious goal of carrying out a large photographic project that would document not only the activities of the Administration but also the lives of farmers and migrant workers across the country. In 1937, the Resettlement Administration became part of the US Department of Agriculture under the name of the Farm Security Administration (FSA). By 1945, FSA photographers had taken nearly eighty thousand pictures of American life during the Great Depression.

Dorothea Lange joined the FSA photographers’ team in 1935.

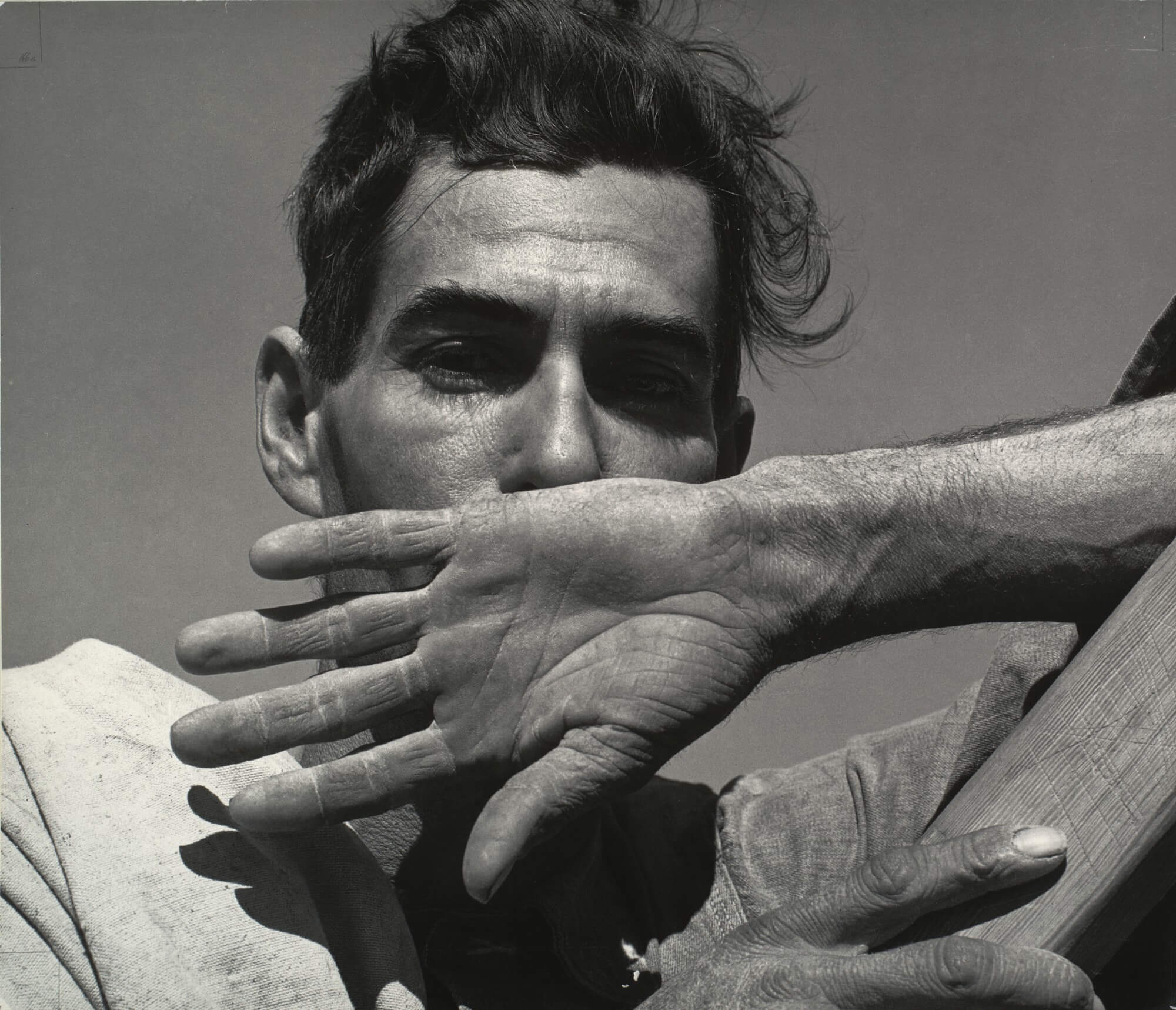

Migratory cotton picker, Eloy, Arizona, 1940 National Gallery of Art

Showing America to Americans. Dorothea Lange’s sympathetic camera

Dorothea Lange was born in 1895 into a German immigrant family in Hoboken, New Jersey. She contracted polio at age 7 with complications on her right leg that left her partially crippled in one leg and with a permanent limp. She always mentioned this peculiarity as crucial for the formation of her personality and the deep understanding of those in need.

Lange studied photography at Columbia University in New York, moving to San Francisco in 1918 where she opened a portrait studio. At the beginning of the Great Depression, she saw the homeless and unemployed on the streets every day, and she could not stand apart from it. It was then that Lange forever stepped out of her own studio’s and onto the street, taking photographs and conveying her sadness and despair through photographic images.

Man beside Wheelbarrow, San Francisco. 1934 MoMA

One of her most famous photographs of the period depicts a crowd waiting to get free soup from a charity. Most people can be seen from behind, with a mixture of different hats – from expensive ones to cheap caps – an indication that the Great Depression spared no one. In the front is an old man leaning on the fence with folded arms, a tin mug squeezed convulsively in his hand. We cannot see his eyes, but the line of his mouth, sealed in despair, speaks volumes.

The White Angel Bread Line. San Fransisco, 1933 National Archives

Photographs of the unemployed quickly gained attention. Economist and professor at Columbia University Paul Taylor saw them at a show in Oakland and later used them in his article about the labor market. He then advised that Tugwell make the photographer an FSA project crew member.

Unemployment benefits aid begins. Line of men inside a division office of the State Employment Service office at San Francisco, California, waiting to register for benefits on one of the first days the office was open. They will receive from six to fifteen dollars per week for up to sixteen weeks. Coincidental with the announcement that the federal unemployment census showed close to ten million persons out of work, twenty-two states begin paying unemployment compensation. 1938 Library of Congress

Upon joining the FSA team of photographers, Dorothea Lange traveled the country for 5 years following the migrant workers from California to the Southwest and South photographing their lives. She was accompanied by Paul Taylor, who interviewed and collected statistics, whilst Lange took photographs. The couple got married during their first trip to New Mexico.

Photographs of migrant workers in overcrowded cars, residents of tents in the fields, in the city dump or in temporary camps, give not only a telling picture of the crisis and uncertainty but also express Lange’s profound respect for these people.

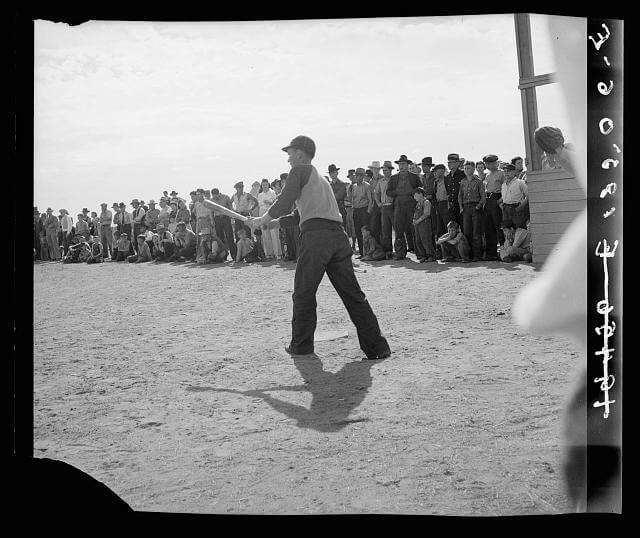

Ball game. Shafter migrant camp. California. 1938 Library of Congress

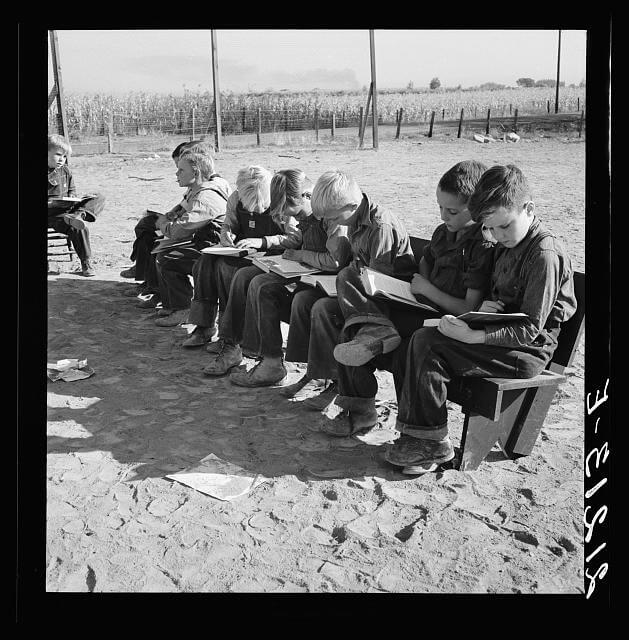

Eight boys at Lincoln Bench School. Born in six states. Near Ontario, Malheur County, Oregon. 1939 Library of Congress

Even the photograph of an abandoned house speaks like a living thing – “Tractored-out!” – a phrase that was on the lips of hundreds of destitute farmers.

Power farming displaces tenants from the land in the western dry cotton area. Childress County, Texas Panhandle. 1938 Library of Congress

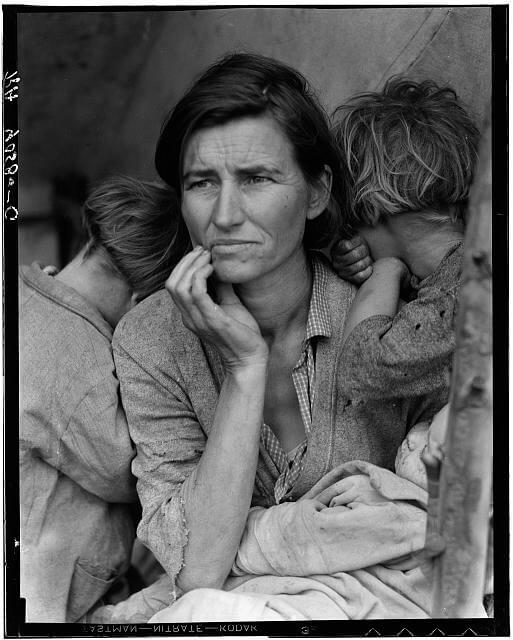

The most widely recognized and circulated image of the FSA photo project, and later of the entire Great Depression era, was Lange’s Migrant Mother.

Lange took it by accident in Nipomo, California, in early March 1936: “We had already passed that section of the road when something seemed to stop me. We made a U-turn, and I approached a woman with children in a lean-to tent on the side of the field. They hoped to get a job picking peas but they were late.” Lange took only seven pictures of a 32-year-old woman named Florence Thompson from different angles. The one with a baby in her arms and two girls cowering behind her and hiding their faces from the camera became famous.

Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California. 1936 Library of Congress

As Drew Johnson, the curator of photography and visual culture at the Oakland Museum of California put it, “The political impact of her work was felt in much the same way as that of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ before the Civil War in creating a heightened public awareness of injustice.”

Thanks to Dorothea Lange’s photographs published in newspapers across the country, it felt as if Americans “saw” America for the first time because, as is often the case, most people knew nothing or were not very much concerned about the scale of the environmental and social catastrophe elsewhere in other states. The photographs turned a distant problem into understandable images that could be sympathized with.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations