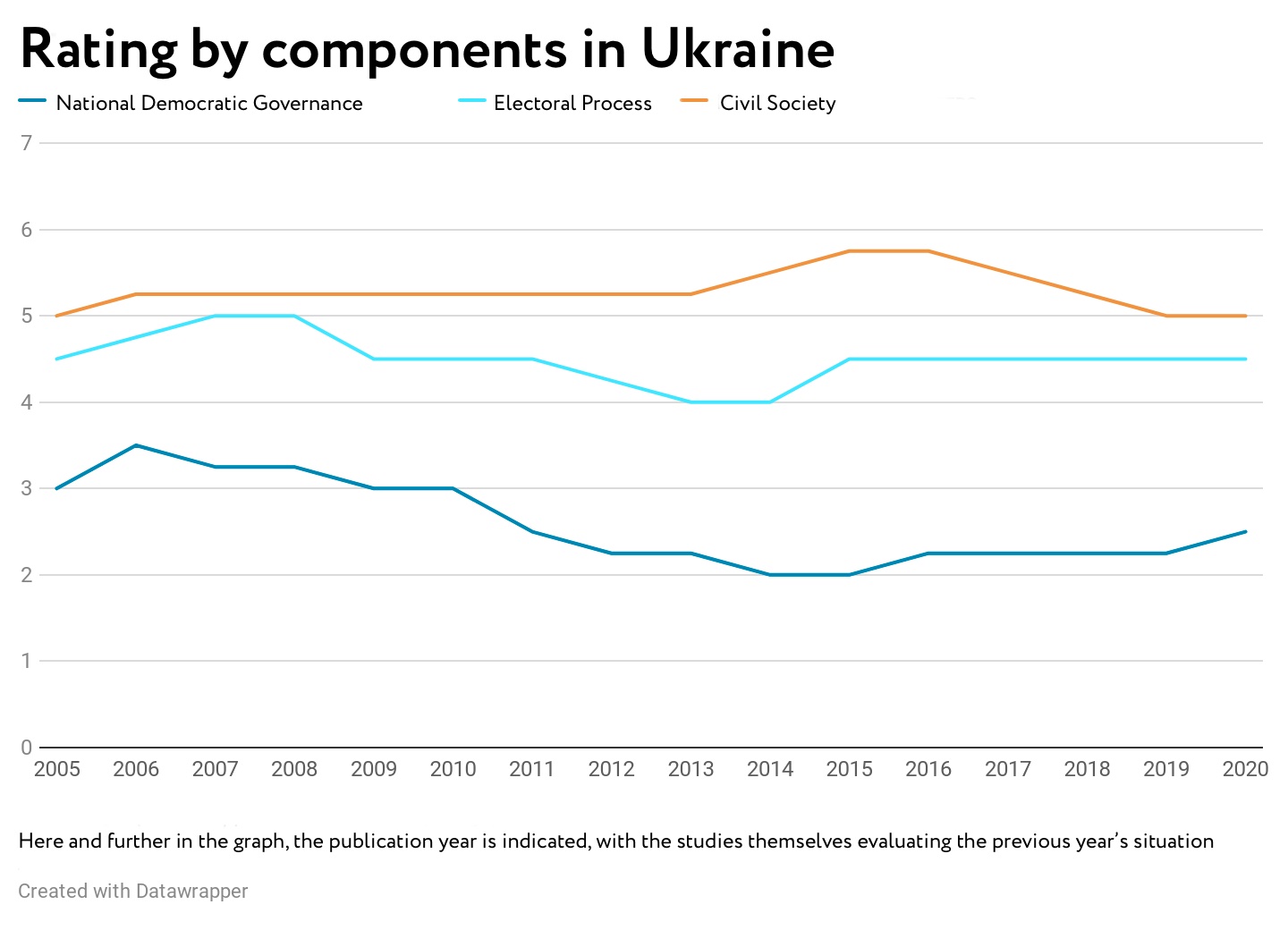

Following the 2019 results, Ukraine received a Democracy Score of 3.39 out of 7 from Freedom House, ending up 16th among the 29 post-socialist countries in Nations in Transit 2020. It is encouraging that Ukraine scores the highest among the countries of the former USSR (excluding the Baltic states), but could we get an even higher score?

To evaluate the state of democracy, Freedom House provides numerical ratings of 1 to 7 with regard to the following seven components:

- National Democratic Governance

- Electoral Process

- Civil Society

- Independent Media

- Local Democratic Governance

- Judicial Framework and Independence

- Corruption

A Democracy Score is a straight average of all the seven components. Freedom House’s work is no doubt necessary and useful both to estimate the internal dynamics of Ukraine’s political situation and compare Ukraine with other countries. However, since democracy indices significantly affect Ukraine’s international image, it is important to understand the intricacies of interpreting such ratings.

In our opinion, the main reason to take Freedom House’s conclusions on Ukraine with caution is the Nations in Transit’s non-transparent evaluation.

A stumbling block: non-transparent evaluation and its manifestations

We understand non-transparent evaluation as a lack of clearly defined and complete rules, norms, and guidelines on which evaluation should be based. This significantly affects the country’s individual components’ ratings and, consequently, its overall Democracy Score. There are at least three aspects where non-transparent evaluation is most pronounced.

Firstly, there are no clear rules for rating by components. Freedom House experts have a checklist of questions that help them describe the situation e.g. with regard to a country’s judicial framework or corruption. But how does this description turn into an evaluation?

For example, as regards Ukraine’s Civil Society, attacks on activists, NGOs’ dependence on foreign funding, the rise of the extreme right, etc. are cited. This, indeed, gives an idea about civil society in Ukraine, but how can this qualitative description be quantified? By how many points should the country’s score be reduced due to attacks on activists or other negative trends?

The readers do not know the clear parameters that would define for what exactly and how many points are to be withdrawn, being left to assume that the author’s own reasoning is the basis for assigning a score.

Another example of the lack of clear evaluation rules is the description of the electoral process: “Ukraine held presidential and snap parliamentary elections in 2019 that proceeded in a transparent and competitive manner… Verkhovna Rada voted on a new Electoral Code.. whose amended draft was signed by president Zelenskyi in December 2019. On April 21, 73% of Ukrainians voted for Volodymyr Zelenskyi…, who later dismissed the legislature.. and in the snap parliamentary elections… the president’s Servant of the People party created a single-party parliamentary majority.”

The above description, indeed, allows us to understand what happened in Ukraine, but how are we to understand what numerical rating Ukraine should be ascribed based on this description? Only the last point in the description of the electoral process barely points to a negative phenomenon: “Encouraged by the election victories, the president’s team considered early elections at the local level, as well. However, implementing these elections would require amending the constitution… Considering these limitations, the government postponed local elections… ”. It remains unclear whether this event (that never happened) affected the Electoral Process rating of Ukraine.

Due to the lack of clear rating rules, the question arises: Do the ratings really reflect the existing problems? Due to what problems did Ukraine get exactly 4.5 out of 7 pts for the Electoral Process?

Therefore, in lack of clear rating criteria, the expert uses her own values to analyze the situation in the country to assign a rating.

In addition, the situation in the country is evaluated by only one expert. The study concludes as follows: “The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s).” The reader only knows the author of this study on Ukraine but has no idea who the reviewers and advisers were. Rating Ukraine by several experts independently of each other would make it more reliable.

Secondly, Freedom House does not always clarify its attitude toward certain events in the country under study, so the reader does not know how those events affected a specific component’s rating.

For instance, according to the description regarding Independent Media in Ukraine, “In July, Ukraine’s new language law came into effect. The law requires that a minimum of 90 percent of airtime on national TV should carry content in the Ukrainian language. Local channels are allowed no more than 20 percent of non-Ukrainian language content…The print media may publish materials in other languages provided that the same content is duplicated in Ukrainian.”

It is not obvious whether this event is interpreted as positive or negative, given the existence of different opinions on the language law in Ukraine. The Freedom House expert’s opinion on it does not become clear from the above description. So, the reader is left unaware of whether Ukraine gained any points for the language law, or, on the contrary, lost them (let alone the grounds for their specific number).

The same applies to Internet regulation. Although there is a separate sub-question in the Independent Media component devoted to this issue, the study only states that “Internet regulation, security, and freedom has become an important issue for Ukraine’s new Ministry of Digital Transformation.”

Freedom House’s negative attitude toward Internet restrictions can only be understood from another study, Freedom on the Net, which calls Ukraine a country with a partially free Internet. In this study, Freedom House points out that Ukraine justifies blocking Russian and separatist websites, arrests of individuals for disseminating anti-government propaganda online, etc., by a need to combat Russian information aggression.

However, despite a declared understanding of the context, Ukraine’s ratings for said components are lowered. This allows us to conclude that Freedom House does not recognize these measures as fitting, despite Ukraine’s necessity to protect itself against Russian aggression, including in the information space. This approach is debatable, because, in our opinion, adequate assessment requires that one distinguish between the security measures the state is forced to take, and pernicious or unjustified restrictions by the state on the citizens’ rights to access information.

But most importantly, Freedom House researchers’ attitudes toward Internet restrictions will remain largely unknown to Nations in Transit readers, as they are not articulated in the report.

So, in addition to the fact that experts have to use their own values when assigning ratings, the reader is not always familiar with those values. A partial solution to this problem would be detailing how many points the answer to a specific question provided to the expert added to or subtracted from a country. In this way, the reader would understand how the language law, Internet regulation and other factors contributed to the Independent Media component’s rating, which would make the evaluation process more transparent.

Thirdly, Freedom House does not always take into account the previous ratings, which results in a loss of consistency.

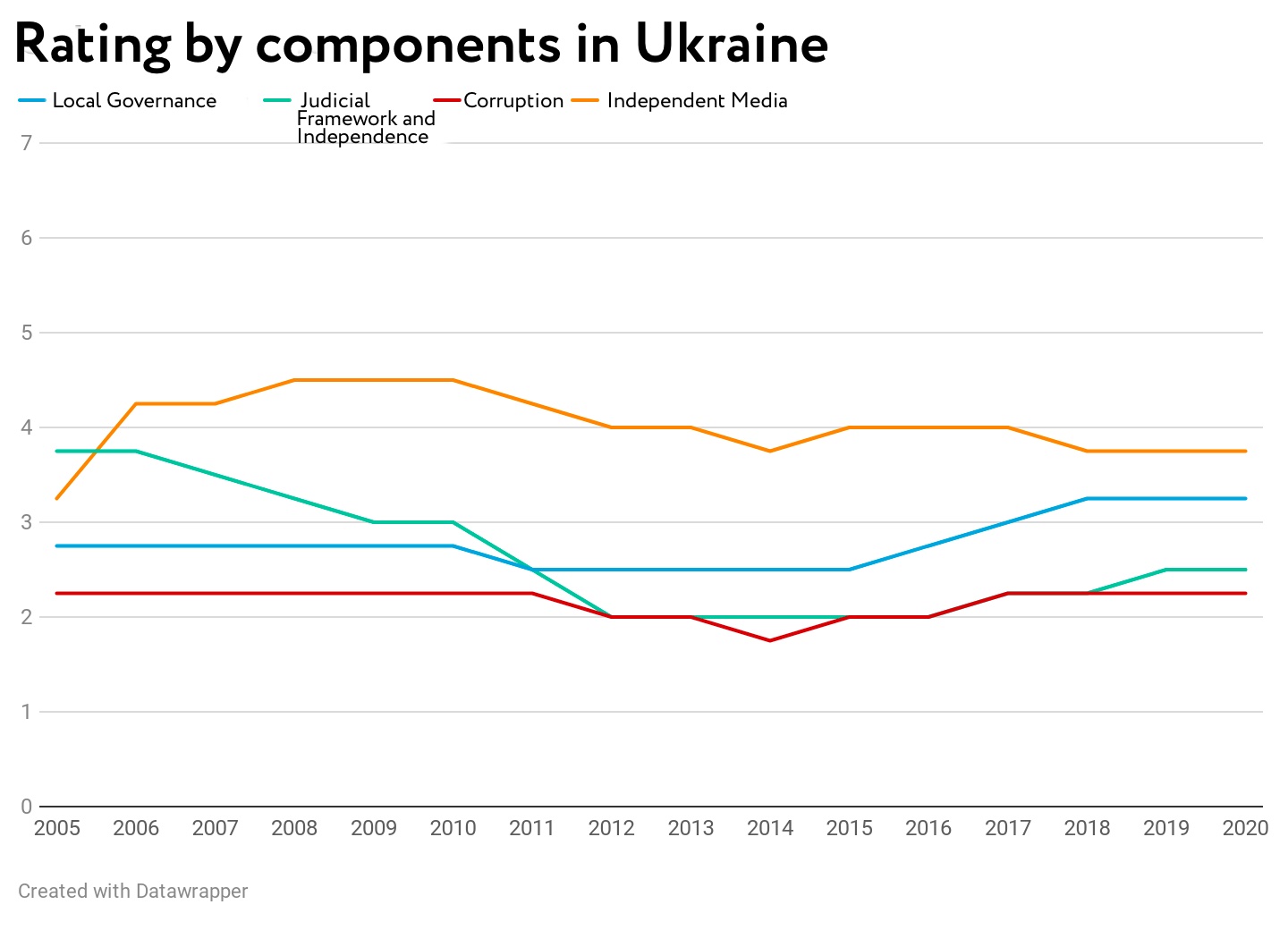

For example, in each study from 2017 to 2020, Corruption received 2.25 points. But has there really been no change? During this period, the Supreme Anti-Corruption Court, NAPC, and SAP were established. Also, the scale of corruption is nowhere near that in the pre-Maidan period.

The study reports: “… NABU launched 533 investigations of high-level corruption, mainly of state-owned enterprises. These actions helped to recover over UAH 107 million ($3.96 million) in damages to Ukraine. NABU has brought to justice 139 individuals, and 70 have been convicted. However, the agency’s efficiency has been undermined by delays at the High Anti-Corruption Court,where some cases have languished without prosecution for more than two years.”

Obviously, new achievements occurred in 2019. But do the delays at the HACC negate the aforementioned successes in the fight against corruption, that the rating remains unchanged? Ratings should reflect trends in the country, but when the country’s corruption situation changes with the rating remaining the same, then it simply does not reflect the true state of affairs.

Ukraine’s Electoral Process is given 4.5 points in both the 2005 and 2020 studies. But the 2004 presidential election was marked by rigging, intimidation of the opposition, violations of freedom of speech, and a need to re-vote in the second round. Conversely, the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections were held on a democratic and competitive basis, as evidenced by the OSCE, the civil network OPORA, and the Ukrainian World Congress (UWC). The new Electoral Code was another achievement.

Then why did Ukraine’s Electoral Process rating not increase, unlike the election’s quality? This chronological inconsistency is reinforced by the fact that the extent and direction in which certain phenomena change the country’s ratings remain unknown. Another problem is that Freedom House does not clearly list the standards a country must meet in order to get the maximum score. Therefore, experts are forced to use their own idea of an ideal state of affairs when conducting evaluation. How the previous years’ ratings are taken into account, if at all, is unknown to the reader.

It should be noted that, the UWC’s recommendations cite Ukraine’s need to combat Russian disinformation. But now a dilemma arises: in order to improve the quality of elections, Ukraine needs to protect its information space, including a ban on certain Russian resources, but this, as already noted, will lead to rating deterioration regarding Independent Media (and vice versa).

All three of these manifestations of non-transparency require a comprehensive solution:

- Creating comprehensive standards to be met by a country to obtain a score for each component.

- Experts’ detailed answers to questions specifying the number of points a country loses or gains for them.

- Taking into account a country’s dynamics in time when evaluating the components.

Trust and verify: how should we interpret the study’s results?

In addition to the above limitations, to interpret the index competently, one should take into account several of its characteristics. First of all, the fact that the total score simplifies the results of the components, being calculated as their straight average. The equivalence between the components already raises questions too. Could we say that a country without fair elections and without corruption is the same in terms of democracy as a country that has problems with corruption, but, despite that, has fair elections?

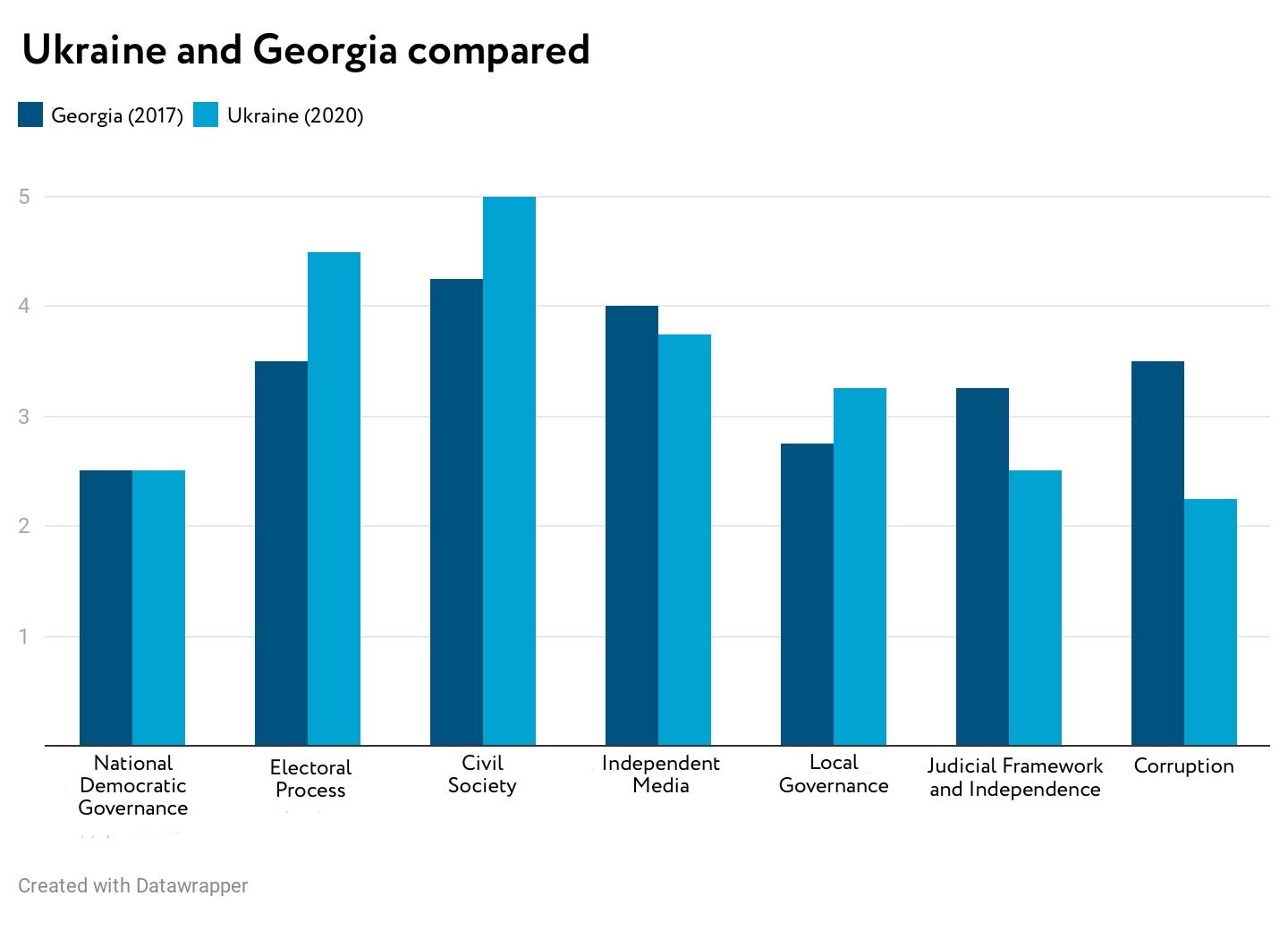

However, the total score and status rating that provides grounds to consider some countries more democratic than others is based on the total score. Due to the straight average, several countries may have the same or very close scores but differ greatly with regard to the components. For example, Georgia in 2017 and Ukraine in 2020 received the same Democracy Score, but the difference in components indicates qualitatively different states of society:

Interpreting the final score as “Ukraine in 2019 is equal to Georgia in terms of democracy in 2016” will be fundamentally wrong precisely because of the differences in the components’ ratings.

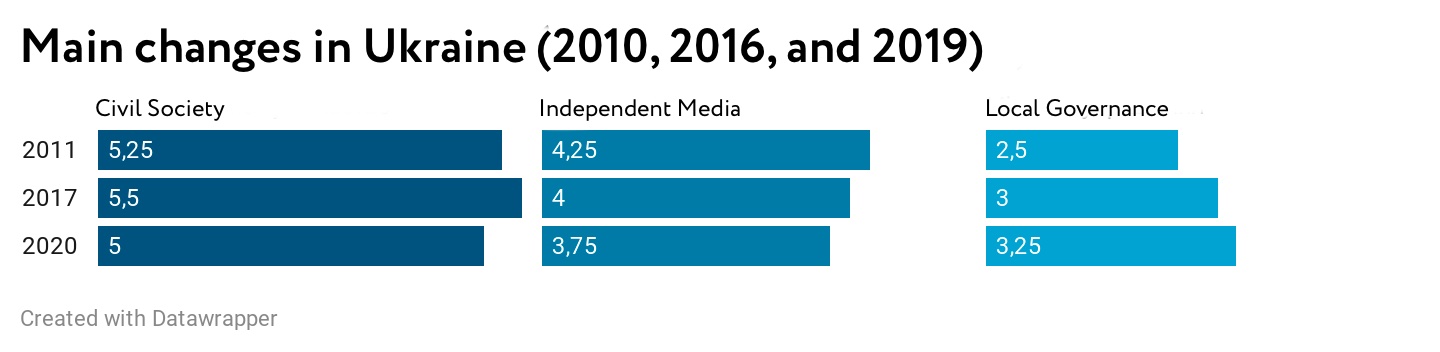

The same applies to one country in different years. For instance, in 2011, 2017 and 2020, Ukraine had the same Democracy Score (3.39) but changes in the components (it should be reminded that the ratings are assigned for the previous year). That is why it is impossible to say that, for instance, “Ukraine in 2019 returned to the 2010 level.”

Even if the total score is somewhat different due to the difference in the components, it is not possible to state unequivocally that one country is more democratic in relation to another. This year, Ukraine’s total score is higher than Georgia’s – 40 points against 38 – but Georgia has a better situation regarding Corruption and Judicial Framework and Independence. Since the components play a key role in the correct interpretation of the results, it would be useful for Freedom House to assign ratings based on them.

Therefore, the total score’s value should not be exaggerated, nor should media headlines such as “Freedom House rated democracy in Ukraine at 3.36 out of 7” be treated as holy writ. And since the media directly influences people’ opinions, in order to consciously analyze the results of Freedom House’s research avoiding misinterpretations, we recommend that both journalists and readers remember the following:

- Rating scores are somewhat subjective and assigned without transparent and clear standards, so ratings should be relied upon to track global trends rather than get accurate measurements or comparisons.

- Freedom House, unfortunately, does not always take into account the local context (particularly in matters of Internet regulation), so the total score may be underestimated.

- Comparing total scores to previous years is not always correct, as significant qualitative changes are sometimes not reflected in the rating.

- The total score does not make it possible to understand the state of democracy in Ukraine – for that, you should look into the components’ ratings.

- To get a full picture of the state of democracy in Ukraine, Freedom House’s study results should be compared with other organizations’ findings and with other indices (Polity IV, Varieties of Democracy, etc.).

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations