The quality of Ukraine’s labor force is often mentioned as one of Ukraine’s key competitive advantages. For example, the OECD’s ‘Ukraine: Sector Competitiveness Strategy’ report of July 2012 singles out Ukraine’s ‘well qualified labour force’ as one of Ukraine’s 4 competitive advantages and indicates that “Ukraine has universal literacy and high general school enrolment: the combined gross enrollment ratio in education of both sexes was 90% in 2009, higher than in some OECD countries.”

Similarly, Ukraine’s recent promo-video ‘Open for U’ heavily relies on the quality of Ukraine’s labor force. Among the 25 selling points mentioned, 7 relate to the quality of its labor force: ‘ 16000 IT graduates each year’,‘Top 3 Certified IT professionals globally’,‘ 99.7% literacy rate’, ‘ 4th most educated nation in the world’, ‘130000 engineering graduates’, ‘640000 graduates each year’ ‘5000 aerospace graduates each year’.

And indeed on some indicators, Ukraine’s labor force scores quite well. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, Ukraine scores 31st (out of 144 countries ranked) in terms of primary education enrollment rate, 41st in terms of secondary education enrollment rate , and even 13th in terms of tertiary education enrollment rate. These are relatively good scores, to some extent when one compares Ukraine internationally, but especially when compared to Ukraine’s overall competitiveness ranking of 76th.

Week of Human Capital

Olga Kupets: The Quality of the Ukrainian Workforce is Quite Low (Olga Kupets, Associate Professor, Economics Department, National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy)

Mariya Aleksynska: Ukraine’ s Low Labour Productivity: Who is Truly Responsible (Mariya Aleksynska, economist, International Labour Organization)

Despite these relatively good scores in terms of how much and how long Ukrainians study, the measures of what Ukrainian labor produces are disappointing.

The average wage in Ukraine is low, currently at about 4000 UAH per month, which according to a Wikipedia comparison makes Ukraine the lowest wage country in Europe.

Other indicators of labor productivity aren’t impressive either: the World Bank estimates Ukraine’s Gross Domestic Product per capita at about 3000 USD, Ukraine’ Gross National Income at about 3500 USD. This level of GDP per capita makes the World Bank classify Ukraine as a ‘Low Middle Income country’, a classification Ukraine share with countries like Mauretania, Bolivia or Mongolia.

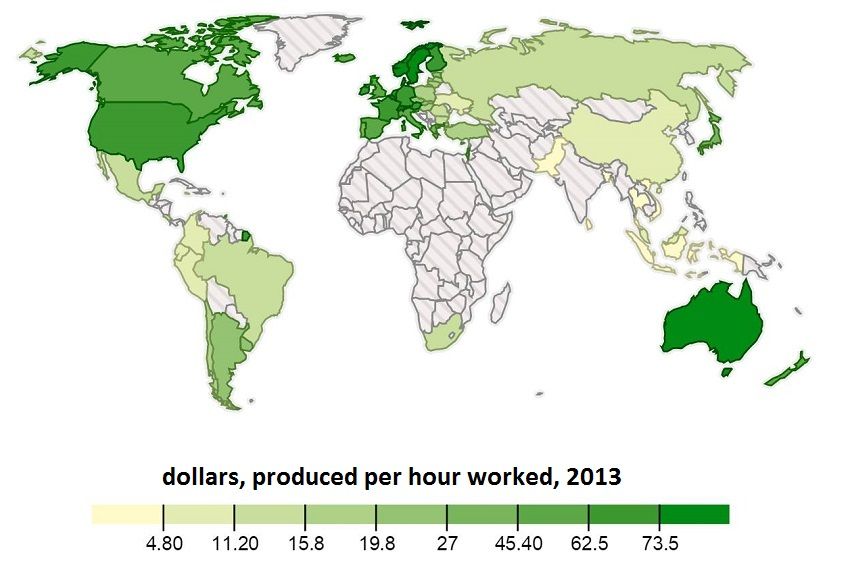

Rather than using GDP per capita to compare labor productivity across countries, researchers have argued one should look at the GDP per hour worked, since the average number of hours worked per year and employment rates vary across countries. But making such correction doesn’t help Ukraine’s performance – out of 63 countries ranked this way, Ukraine scored 56th with about 5$ produced per hour (Upload the data). 5$ per hour of work is similar to China, but only a third of the value produced per hour in Poland or Russia, and about 5% of the value produced per hour of work in Switzerland.

The statistics above thus suggest that Ukraine is not able to transform ‘years of education’ into ‘wages’ and ‘measured production’. This inability can be explained by a combination of several factors.

First, in Ukraine, part of the production is not measured in official statistics. But even if one assumes Ukraine’s shadow economy is as big as its official economy, that this would imply in Ukraine 10$ per hour is produced, and that there is no shadow economy in other countries, this would only push Ukraine to 52nd out of 63 countries.

Second, while Ukrainians study for many years, it’s less clear how much is learned over these years since Ukraine scores not that well in terms of the quality of education. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, Ukraine scores 40th (out of 144 countries ranked) in terms of quality of primary education but only 72nd in terms of quality of the [higher] educational system and 88th in terms of quality of management schools. Moreover, Ukraine scores very bad in terms of retaining talent (132nd): Jan Koum and Max Levchin who are featured in the ‘Open for U’ promo-video as ‘born and raised in Kyiv’, both left Ukraine for the United States at the age of 16.

But despite the mediocre quality of education and the migration of many talented individuals, business in Ukraine does rarely see lack of qualified staff as a major problem for business: less than 5% indicate it is the most problematic factor in Ukraine. Moreover, companies in Ukraine do not invest much in the education of their staff (Ukraine ranking 92nd on this criterion). This suggest that limited skills are not the main reason for the low productivity of labor in Ukraine.

Probably the most important reason for the inability of education to be transformed into significant value comes from the poor performance of Ukraine of what the Global Competitiveness Report calls the ‘basic requirements’ on which Ukraine ranks only 87th, which includes the quality of the Institutions ( on which Ukraine ranks 130th) and the Macroeconomic environment ( on which Ukraine ranks 105th). Even a high quality labor force will have a hard time being productive in a hostile environment.

Such complementarities between different factors that affect economic growth also lead to complementarities between different reforms. This implies that reforms in one area of the economy (like institutions) can affect the effectiveness of reforms in other areas (like educational reforms) but also that lack of reforms in a given area can make reforms in another area ineffective. For example, improving the educational system in Ukraine is unlikely to give a sizeable boost to labor productivity if the institutional framework is not improved simultaneously. Comprehensive reforms are thus Ukraine’s best shot at noticeable progress.

Notes

1.GDP per hour worked is computed based on data from the World Bank

2. Employment is computed based on Ratio Employment to population over 15

5. Average hours worked are from The Conference Board. Ukraine is not included in this database – I estimate the number for Ukraine at 1800 hours per year.

6. A UNECE report mentions a norm of 1920 hours, while ILO’s decent work Ukraine Country profile mentions about 1700 hours in 2008.

7. 1800 hours also falls in the range of other Eastern European Countries. Moreover, using 1700 or 1900 hours does not make much of a difference.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations