The decision of the President Volodymyr Zelensky to hold early elections to the Verkhovna Rada created a unique situation when two election campaigns – first presidential and now parliamentary, passed one after the other. Political scientists have repeatedly emphasized the importance of the types of electoral systems, the advantages and disadvantages of applying both a proportional and a majority model, as well as the ability of each of them to favor a particular political player.

It is not very popular and researched at the same time, but the situation with polling stations is very illustrative, because it can tell a lot about the democratic elections in the country. While Ukrainians are waiting for the announcement of the election results to the Verkhovna Rada, we want to share with you the results of our study and analyze how they voted in the recent presidential election in penitentiary institutions.

Voting in the places of detention (incarceration)

The general public in Ukraine knows almost nothing about elections in places of incarceration: very few pieces of news about the use of coercion and administrative resources behind the bars are seeping into the information space. Unfortunately, debates (1, 2) are sometimes triggered by the need to deprive prisoners of their voting rights. In many jurisdictions, judicial and administrative authorities have repeatedly recognized this type of punishment, known in the English language as “disenfranchisement,” or more often, “felony disenfranchisement” (i. e. the revocation of the right to vote for certain period of time or for life for grave and particularly grave crimes). In particular, it was overturned in Canada in 2003, and within two years a similar decision (Hirst (No 2) v. The United Kingdom) was passed by the European Court of Human Rights, whose jurisdiction is recognized by Ukraine. However, the practice of disenfranchisement is still widely used in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, and in particular in the Netherlands, France, Germany, Italy and Taiwan. Different jurisdictions introduce different voting practices and differently determine who, for what crimes, for what time, and at what types of elections to deprive of voting rights.

Although often discussed in a normative legal acts way, it should not be forgotten that it can also have quite specific political implications. For example, in the United States which have the highest number of prisoners per hundred thousand population among developed western countries, such a policy benefits the Republican Party, since most prisoners belong to racial minorities and the poorest people who are inclined to vote for their competitors – Democrats.

The guarantees of the voting right of prisoners are formally intact in Ukraine but in practice the situation is more complex. For a long time, the use of administrative resources has been a threat to the democratic process – prison voting could be a tool for fraud. Thus, in the 2012 parliamentary elections, the Party of Regions won in all but two of the country’s penitentiary establishments; in a number of prisons the incumbent party then got more than 90% of the prisoners’ votes. Until 2014, the OPORA Civil Network recorded in the colonies various practices of coercing convicted persons to vote, while informants also reported cases of bribery, coercion and violation of the secrecy of voting. However, from the words of the informants and the results of the voting, it can be concluded that during the 2014 presidential election coercive practices were at least weakened. For example, in the 2010 presidential election 71% of the polling stations almost unanimously supported one candidate compared to just 44% in 2014.

Like almost everywhere in the post-Soviet territories, prisons in Ukraine are divided into so-called “red” and “black” ones. In the scientific literature, this phenomenon has been described, for example, by Soviet and Russian sociologist Alexei Levinson. In “red” prisons, all processes are controlled by the administration, and in “black” ones by “thieves” and “overseers” (protectors)” (i.e. the representatives of the criminal world). A prison being “red” or “black” has a key role in elections: the “red” ones force prisoners to vote for a particular candidate, while the “black” have a lot more freedom of expression.

The above facts allow us to understand the political implications of the debate on suffrage in Ukraine and in the world. They also help to realize that the complexity of the problem of securing an expression of will behind the bars is not limited by the relevant legislation, but is shaped by a number of extra-legal factors, institutional culture and political environment.

How did prisoners vote in Presidential Elections?

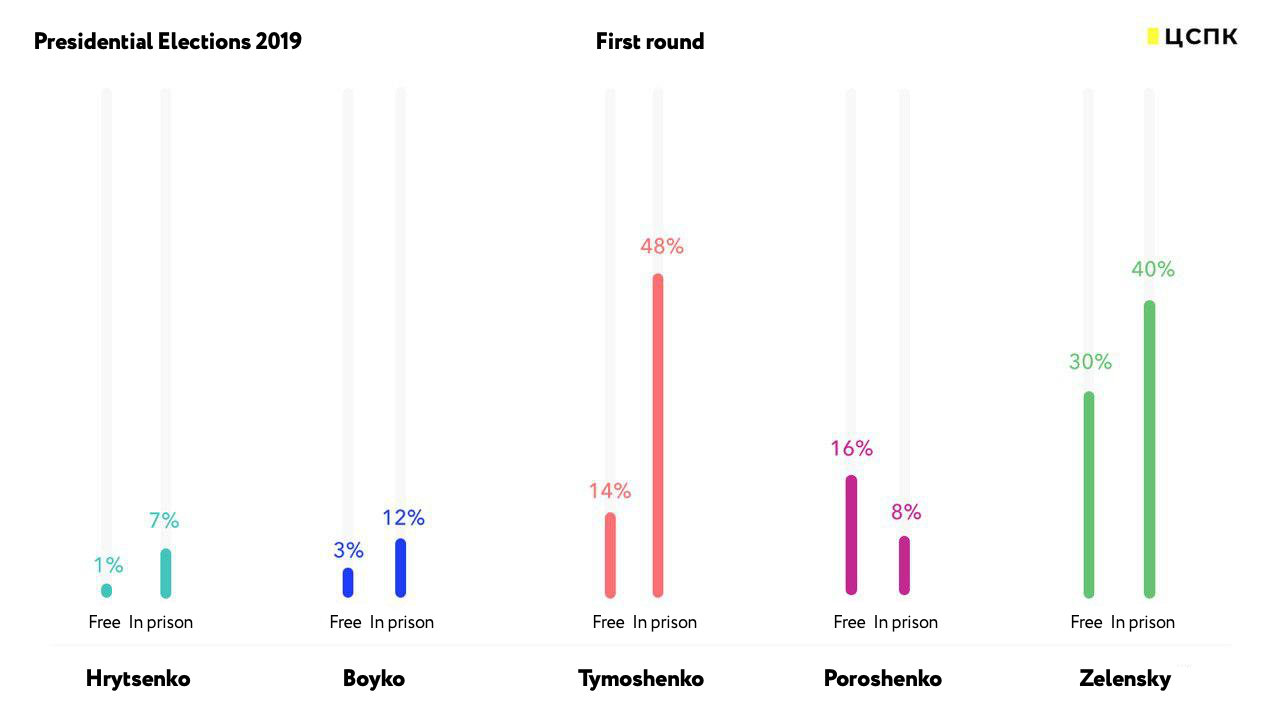

After the first round of the 2019 presidential elections the main news was the victory of Yulia Tymoshenko in the Kachanivka correctional colony where the ex-premier was imprisoned before. In fact, in the first round Tymoshenko won an absolute majority of the prisoners’ votes in all prisons in Ukraine. Given that in the 2010 and 2014 presidential elections most of those serving their sentences cast their ballots for Mrs. Tymoshenko, one can certainly talk about the trend. At the same time, it is interesting that in the entire Ukraine in 2014 and 2019 elections the candidate was supported by only about 13% of voters. The distribution of votes is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Presidential Elections-2019 results for the first round

We do not yet have an exhaustive explanation for this phenomenon. However, for Ukraine this tendency is relatively new, and its start coincides with two phenomena: first, the gradual rooting of the tradition of free elections and, second, consolidation of ‘their’ [core] voters by political parties. Previously, there was a clear tendency in prisons to vote for those in power, now they voted for Yulia Tymoshenko although she had no significant influence on state policy. In fact, as in the case of the inclination of US prisoners to support the Democratic Party (in states where this is legally possible), we can assume that in the Ukrainian context the question of who is serving the sentence has played a major role. Irina Bekeshkina, Director of the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation has pointed out that the less well-off voters voted mainly for Tymoshenko, Lyashko, and Boyko – those whose rhetorics seemed to them more sensitive to social problems. However, this issue needs further study. Equally striking is the difference between support for Petro Poroshenko and Yulia Tymoshenko in prisons compared to their support in Ukraine as a whole. In the 2014 presidential elections, the winning Poroshenko received about 30% of prisoners’ votes, while the Batkivshchyna leader won more than 50% in the places of incarceration. At this year’s presidential election, the so-called “protest vote” in the penitentiary institutions was even more significant.

“Each of us is the President”: from support of the power to support of the opposition

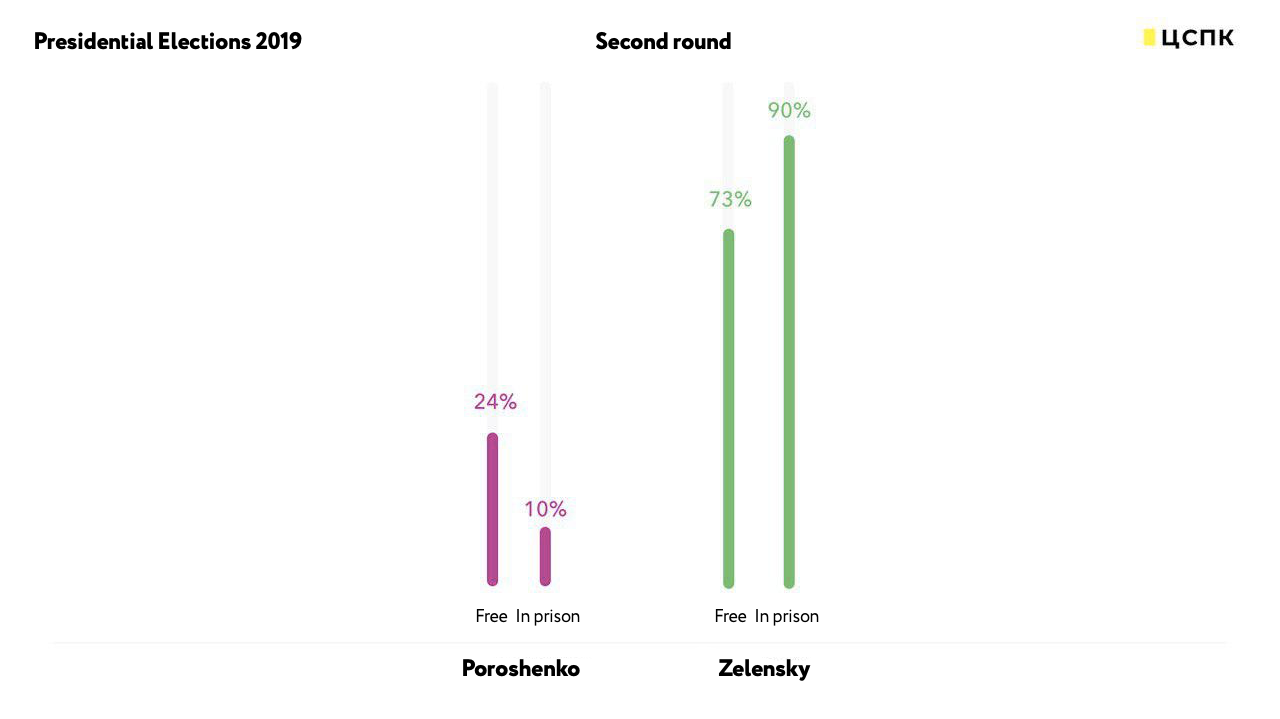

During the second round of the presidential elections in prisons the tendency to vote strongly reflected the general trend in Ukraine: a larger percentage of the prisoners who voted supported Volodymyr Zelensky’s candidacy than Ukraine as a whole.

Figure 2. Results of voting in the second round of the presidential elections in places of incarceration compared to the general results.

The distribution of votes in most places of incarceration during the last presidential election suggests that prison administrations did not use coercion as a tool to directly control the will of detainees, but the results of voting in certain prisons suggest a possible “incentivising” of detainees to vote for a particular candidate. It seems that the forecasts of falsification on special polling stations have been refuted and the trend has been broken. In fact, we have a reason to speak of a gradual departure from the established “tradition” when prisoners have been a mainstay for politicians in Ukraine. Moreover, we are witnessing new trends where, in the absence of pressure, prisoners tend to vote for opposition. These processes need to be thoroughly researched but the dynamics of the distribution of votes in detention places are pushing for answers to the question of how social and demographic characteristics of Ukrainian prisoners affects their political preferences.

Parliamentary Elections

Special polling stations as a whole, and those in prisons in particular, is an important electoral resource primarily due the voting system. In a majority election system, the votes of prisoners are of considerable importance to those who apply for positions in representative bodies. This makes prisons extremely vulnerable to bribery and fraud.

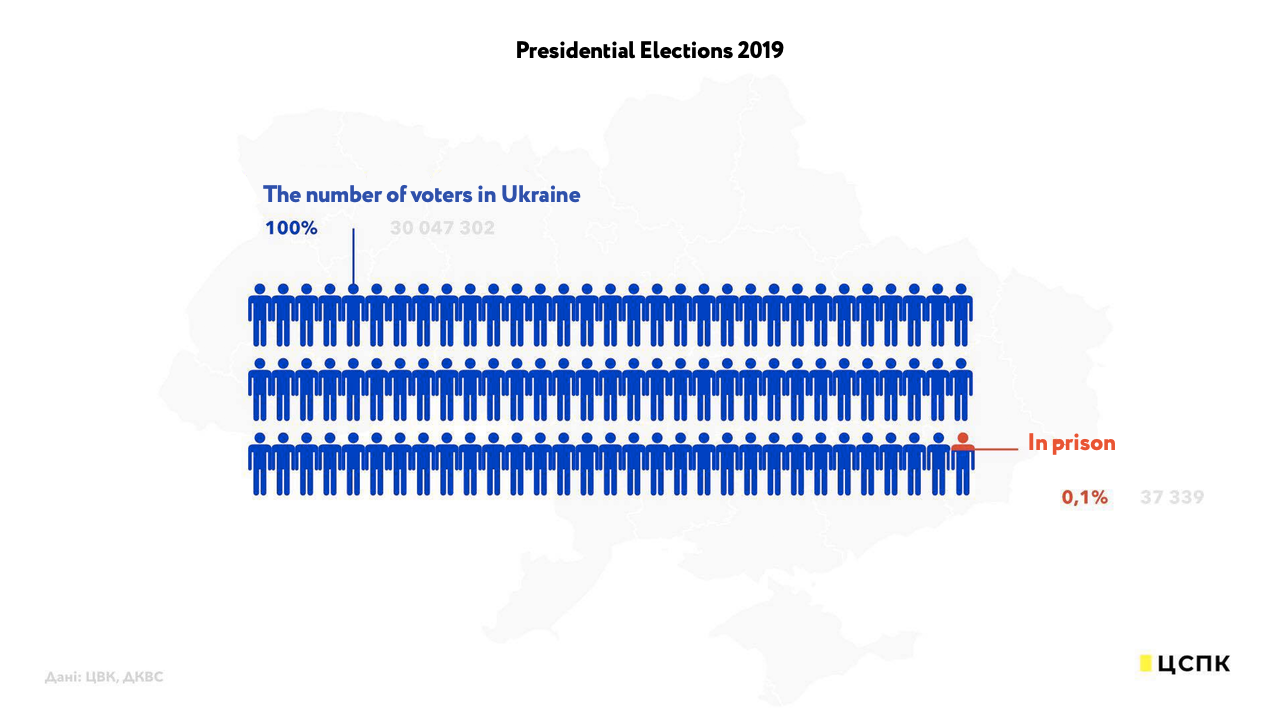

Under the proportional system, the fraction of prisoners who vote in elections simply dissolves among the total number of voters in Ukraine. And if the single-mandate system once finally goes into oblivion, Ukraine will receive an additional guarantee of eradicating the shameful practices of coercion to vote in places of incarceration at the directions of administration.

We hope that along with the single–mandate system, undemocratic rhetoric about depriving prisoners of voting rights will remain in the past as well. However, one should prepare for the attempts of the political forces to play on the issues of security and freedom, crime and (conditions) of punishment, trying to gain voters’ favor on both sides of the barbed wire.

*Limitations of the data shown in the illustrations: the State Criminal-Executive Service of Ukraine (DKVSU) reports 53,330 prisoners who took part in the vote (citing information from interregional departments). At the same time, the SCESU (DKVSU)itself did not provide us with information on the precincts, and the Central Election Commission provided an incomplete list of polling stations of such type. That is, some precincts could be omitted. The total number of inmate votes processed by us is 37,339. At the beginning of 2019, the number of detainees in Ukraine was 54,905 (including minors).

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations