Robert Solow, a Nobel prize winner, suggests that the country can has inflation because it expects inflation, and expects inflation because it has it. Once economy happens to be in such high inflation equilibrium, it is hard to get out from it. Given that Ukraine has had high and volatile inflation since its independence, it may seem that the situation is hopeless and forecasting inflation at long horizons is futile. Yet, this is a wrong view.

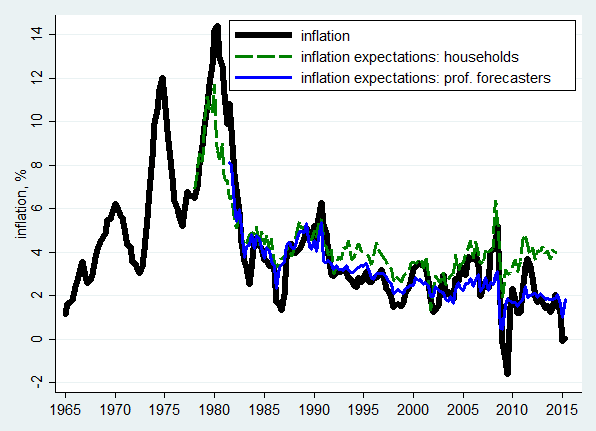

A recent spike in inflation woke up fears that Ukraine can slide to hyperinflation of the early 1990s. Indeed, the government faced a glaring fiscal gap in 2014-2015 and got a tangible fraction of its revenue from seigniorage, that is, printing money. Inflation expectations rose to levels not seen for more than 10 years (see Figure 1). This is a dangerous situation: inflation can become self-fulfilling. In words of Robert Solow, a Nobel prize winner: “Why is our money ever less valuable? Perhaps it is simply that we have inflation because we expect inflation, and we expect inflation because we’ve had it.” Once economy happens to be in such high inflation equilibrium, it is hard to get out from it. Given that Ukraine has had high and volatile inflation since its independence, it may seem that the situation is hopeless and forecasting inflation at long horizons is futile. Yet, this is a wrong view.

Figure 1. Inflation rate in Ukraine

The National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) declared a new monetary regime: inflation targeting. The NBU announced a path for the future rate of inflation gradually decreasing from current heights to approximately 12% in 2016, 8% in 2017, 6% in 2018, and 5% afterwards. As a part of this new regime, the NBU promised to let the hryvnia float. This is a bold step given that many Ukrainians use the exchange rate to measure the purchasing power of the hryvnia, a common misconception and mistake. If one believes this regime change, then the forecast for inflation in 10 years from now should be 5%.

There are two related questions. First, how can one make this regime work in practice? Second, is it going to work in Ukraine?

To answer the first question, consider the standard expectations-augmented Phillips curve, which links nominal variables (inflation) to real variables (output, unemployment):

πt inflation = Etπt+1 inflation expectations – γ*(Ut-U) unemployment gap

This relationship suggests that inflation today depends on expected inflation (the first term on the right-hand side of the equation) and on how much slack one has in the economy (the second term). High inflation expectations translated one-for-one into current inflation and, in this sense, controlling inflation expectations is absolutely crucial. One can also reduce inflation by generating slack, that is, increase unemployment Ut above some equilibrium level U.

Controlling expectations is a challenging task. The NBU has to prove its credibility as an institution averse to inflation. How can this be done? A classic example is the Volcker disinflation in the U.S. in the early 1980s. At that time, the U.S. economy had double-digit inflation. Paul Volcker was appointed to combat inflation. Few people believed that this was a serious attempt and thus the mere fact that Volcker was a new chair of the Federal Reserve System (the Fed) meant little for inflation dynamics. To establish credibility, Volcker had to raise interest rates to unprecedented levels. This policy resulted in the second-largest U.S. recession in the post-World War II era. Unemployment skyrocketed to 10 percent. But it sent a signal that the Fed was serious about inflation. Inflation was crushed: within a few years, Volcker brought inflation and inflation expectations down to 3 percent. In short, Volcker had to use both channels (change people’s expectations and generate unemployment) to disinflate.

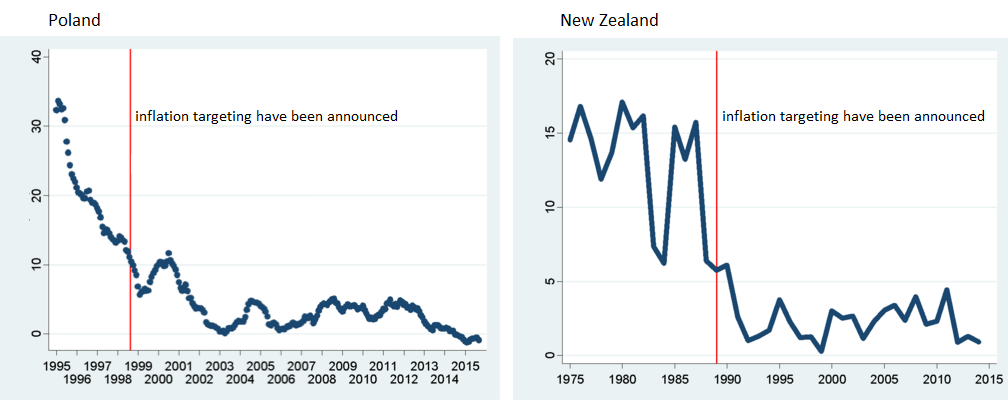

Figure 2. Inflation dynamics during the Volcker disinflation in the U.S.

Notes: the vertical axis measures the deviation of inflation from expected inflation (one-year ahead inflation, Michigan Survey of Consumers). The horizontal axis shows the deviation of unemployment from equilibrium level (approximately 6 percent). The red line shows the slope of the fitted linear regression (parameter γ in the Phillips curve).

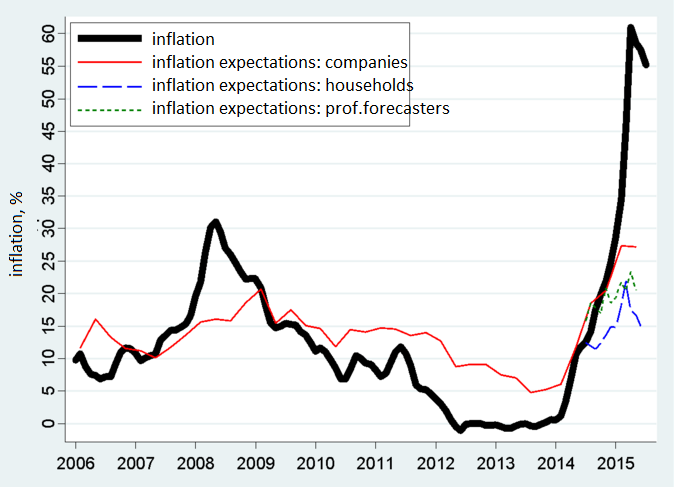

Since Volcker achieved disinflation, inflation and inflation expectations have been in check (see Figure 3). The Fed has established its credibility and now even relatively minor moments in the interest rates controlled by the Fed send a powerful stabilization signal. The amount of credibility is striking: after Fed did massive injections of liquidity into the ailing economy during the Great Recession, there was no great inflation fear.

Figure 3. Inflation and inflation expectations in the U.S.

Source: BLS, Michigan Survey of Consumers, Survey of Professional Forecasters. Inflation is based on CPI

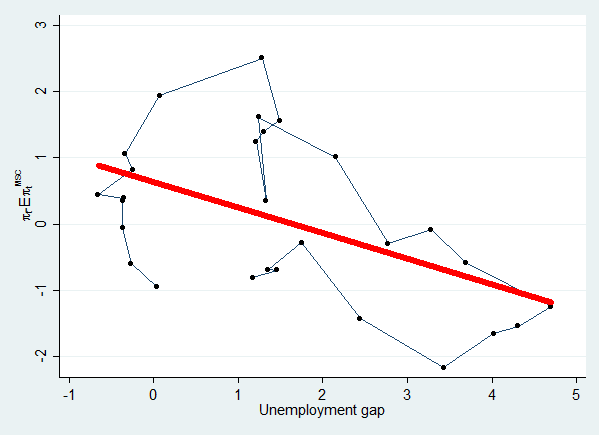

Now we know the answer to the first question: it can be done, but it involves temporarily lower growth or even a recession. To answer the second question, we can examine experience of other countries that used inflation targeting to disinflate and to control inflation afterwards. Figure 4 shows the dynamics of inflation for New Zealand (the pioneer of inflation targeting) and Poland (Ukraine’s neighbor and “role model”). In both cases, inflation was reduced within a few years and remained stable for many years. Even during the recent global finance crisis, inflation was remarkably stable. During the disinflation process, there was no major recession. Is this a general pattern?

Figure 4. Inflation dynamics in Poland and New Zealand

Source: IMF International Financial Statistics

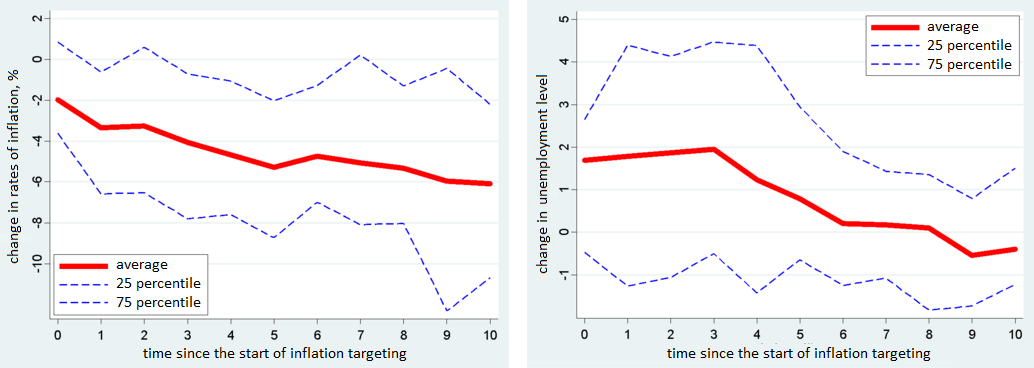

The answer is “yes”. I take all countries that formally adopted inflation targeting and examine how inflation was reduced. Figure 5 presents average dynamics of inflation (left panel) and unemployment (right panel) since the start of inflation targeting. Within a few years, inflation on average is reduced by 4 percent. In the top quarter of cases (countries more successful in reducing inflation), inflation fell by 8 percent. This is not costless. Similar to the Volcker disinflation, the transitional period is associated with unemployment being increased by two percentage points. This is a considerable cost but it is much “cheaper” than the cost during the Volcker disinflation.

Figure 5. Average dynamics of inflation and unemployment since the start of inflation targeting

If inflation targeting works for other countries, is it going to work in Ukraine? The answer depends on the commitment of the NBU to fight inflation. So far, the central bank keeps nominal interest rates well above expected inflation. This is a sign of tight monetary policy aimed at disinflation. So in the short run, the commitment seems to be there. For the longer run, one may note that recent changes in legislation gave more independence and powers to the NBU to ensure it focuses on fighting inflation and is insulated from political pressures. Thus, there is some assurance that the new regime is here to stay. If so, inflation will be about 5% in ten years from now.

How can the NBU make the transition easier? First, communication plays a central role in inflation targeting because it gives the central bank a direct tool to influence and control inflation expectations. The NBU should make every effort to reach out and convince people that the new regime will bring inflation down. Second, given the sensitivity of inflation expectations to the UAH/USD exchange rate, minimizing swings in the exchange rate can help stabilize inflation expectations of households and firms. However, this policy can be used only to the extent it does not contradict the main objective of the central bank: fighting inflation. Third, the central bank and, more importantly, the public should guard the independence of the NBU.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations