Identity is defined as a set of personal reference points on which people rely on to navigate the social world they inhabit. Characterized by a complex social context, Ukraine warranted particular attention to the issue of identity. Divided society, regional heterogeneity, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made identity analysis an important subject of research. This study overviews factors that contribute to self-identifying with the Ukrainian nation, state, and society.

Identity is seen as one’s stance in relation to the human environment, defined by categorizing oneself and others (Hale 2004). Allowing individuals to realize where they belong serves as a cognitive uncertainty-reducing mechanism that facilitates coping with the vast complexity of the social environment (Gaertner and Dovidio, 2012). Since social context has many faces, identities are also recognized as multiple and represent a spectrum of dimensions, each describing one’s stance in a particular aspect of the social world. Ethnic, national, civic, racial, linguistic are only a few examples of identities that disentangle one’s social milieu into specific dimensions.

In choosing one’s stance for each type of identity, the individual moves between two extreme points. The lower end is constrained by a membership given at birth. The upper end is defined by voluntary membership. The individual moves between these two margins choosing any specific location on the continuum of identity stances. In making their choice, people use criteria that are important to them at each particular moment. Scholars argue that these criteria are initially defined and modified by social conditions.

Drawn upon this assumption, the analysis of identity formation in Ukraine focuses on three specific aspects producing three distinct theories about being or feeling Ukrainian. The first theory proclaims that regions shape the identity, ultimately linked to the pragmatic division between the East and the West of Ukraine. Regions were believed to accumulate historical, political, and socio-economic peculiarities, significantly impacting their populations’ identities. Eastern areas were assigned more attachment to Russia-related attributes ranging from speaking Russian to one’s association with Russian ethnos. By contrast, western regions have been associated with more pro-democratic attitudes, intolerance to authoritarianism and crime, and preferences for an independent Ukrainian nation (Kuzio, 2000).

The blurred reality of regional heterogeneity in Ukraine contributed to the emergence of a second theory that focused on the most apparent aspect of societal cleavage between regions – language. Associated with specific interests and viewpoints, language was recognized to shape the individual’s particular beliefs’ structure and behavioral norms that could influence the identity formation process. This theory depicted Ukraine as a country traditionally divided into two linguistic groups (Russian and Ukrainian) and was used by Putin and his minions to picture Ukraine’s reality. Language practice and language preferences were presented by them as the primary markers that divided the society into Ukrainians and Russians.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014 became a third theory in explaining identity formation among Ukrainians. The war created a new reality in the country by strengthening the sense of political unity and state identity. It mobilized the population, including Ukrainian Russian speakers, on the government’s side (Aliyev, 2019). Russia’s further invasion of Ukraine triggered mass ethnic defection that united the population and boosted their sense of civic belonging. The war with Russia increased the notion of Ukrainian citizenship as opposed to ethnic Ukrainian (Sasse and Leckert, 2018). The Russian-speaking minority reconsidered not only their sense of national identity but also their stance toward the Ukrainian language. Many individuals started to identify themselves with the Ukrainian language even without knowing it while perceiving it as the symbolic marker of the country (Kulyk, 2018).

Even though linked to the social environment, political factors have been rarely considered for identity analysis. At the same time, the political process plays a critical role in configuring Ukrainian society. Post-communist transition, independence from Russia’s influence, new pro-democratic ideologies, visions, and attitudes all became important factors shaping contemporary society in Ukraine. This suggests that political considerations could have entered the process of self-identification as an essential criterion defining one’s position on the identity continuum. Whether I identify myself with Ukrainians or Russians could potentially be linked to political ideologies, political visions, and political interests that each nation or state defines as their intrinsic characteristics and inner attributes against which individuals compare their personal beliefs and attitudes’ structures in determining where they belong to. In the case of Ukraine and Russia, it is a perfect line of reasoning since the two countries show a wide gap in their political institutions and political values. Russia is characterized by a hegemonic identity with a preference for authoritative and less democratic forms of governance. By contrast, Ukraine has developed more liberal and pro-democratic institutions while its population has adopted pro-democratic values. Hence, political factors can potentially be an essential criterion in choosing a nation or a country to which individuals feel to belong.

There is still the question of who are those that opt for Ukraine? Which political factors are critical in self-identifying with Ukraine? What political values and preferences should individuals hold to choose Ukraine as their ethnicity, state, and society? This study addresses these issues using the World Values Survey (WVS) as the primary data source. I employ the most recent, seventh, wave conducted in 2020 in Ukraine. My analysis addresses three identity forms – ethnic, civic, and social. Ethnic identity captures the ethnic group that respondents feel to belong to. Civic identity specifies whether respondents feel citizens of Ukraine. Social identity draws upon society and reveals if respondents feel like belonging to their community. I identify what political values and preferences are associated with the selected spectrum of identities in the case of Ukraine.

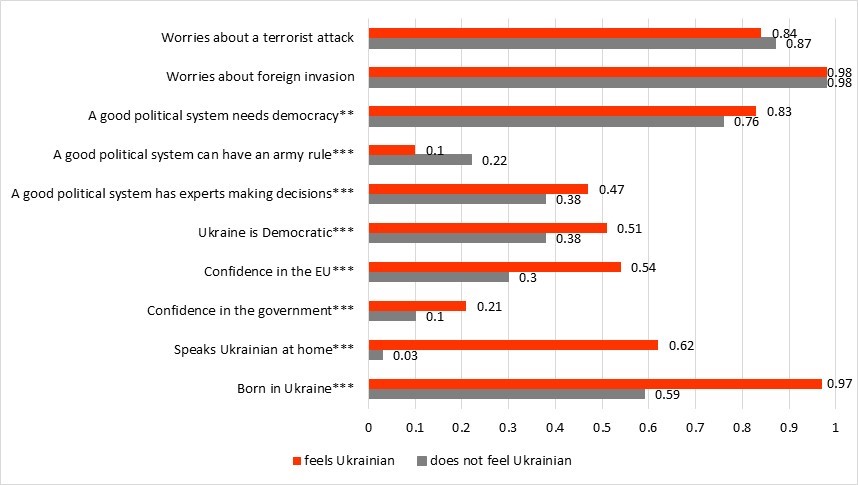

In particular, Figure 1 suggests that feeling a Ukrainian in Ukraine was connected to individuals’ political visions and aspirations. Those who valued democracy as a form of governance in Ukraine and considered Ukraine a democratic country were more likely to identify themselves as Ukrainians. A higher probability of identifying themselves as ethnic Ukrainians characterized the respondents who displayed confidence in the government or a preference for the West, proxied by the trust in the EU. Similarly, respondents, who showed intolerance to the army rule in politics and claimed that experts should instead govern the country, were more likely to choose “Ukrainian” as their national identity. Lastly, people born in Ukraine and using Ukrainian as a primary language of communication at home tended to identify themselves as Ukrainians more often than those born outside Ukraine or using Russian to speak in the family.

Figure 1. Factors of ethnic identity in Ukraine

Notes: (*) refers to the statistical significance in the difference of means between the two groups of respondents. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

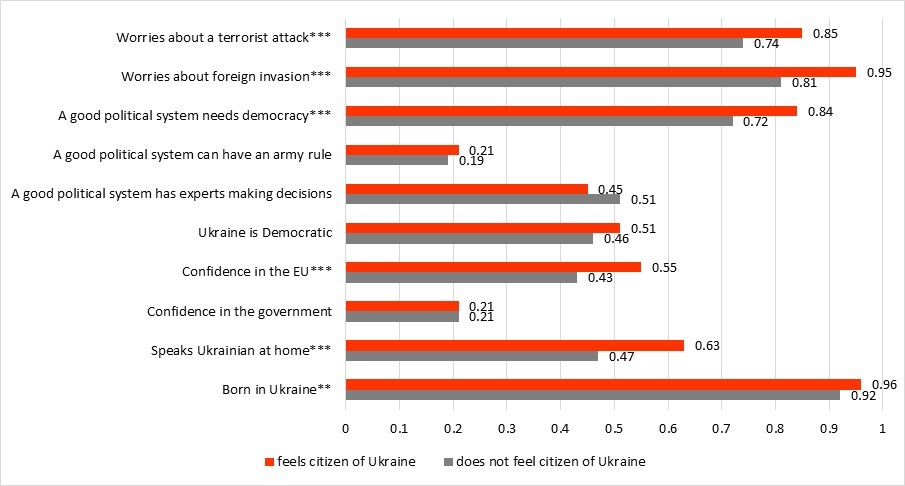

Figure 2 suggests that the formation of civic identity followed a slightly different pattern than national identity. Feeling a citizen of Ukraine was primarily shaped by three factors – democracy, confidence in the EU, and the fear of war. Firstly, individuals who trusted the EU and viewed democracy as a foundation for a well-functioning political system were more likely to identify themselves with the Ukrainian state. Furthermore, respondents who feared war or a terrorist attack in their country were more likely to feel citizens of Ukraine. These findings suggest that the war united the population in Ukraine and increased their dedication to the state. Also, those who used Ukrainian to communicate at home or were born in Ukraine more often felt citizens of Ukraine.

Figure 2. Factors of civic identity in Ukraine

Notes: (*) refers to the statistical significance in the difference of means between the two groups of respondents. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

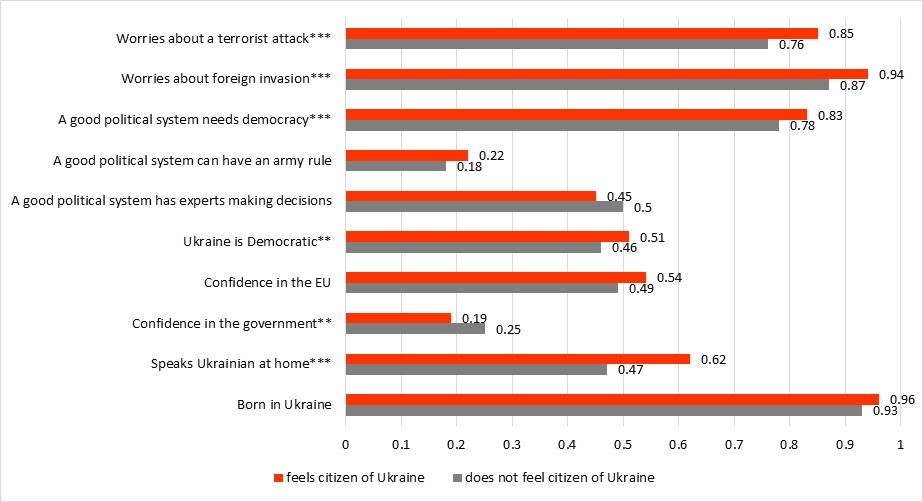

Finally, let’s consider the social identity of Ukrainians, i.e. feeling belonging to Ukrainian society or the community (figure 3). Language spoken at home was an essential factor for this identification. In addition, social identity has a clear connection to democracy and political trust. Those who thought Ukraine was democratic were overrepresented in the group of respondents who opted for Ukraine as their social identity. Like in the case of civic identity, the threat of invasion or attack contributed to consolidating Ukrainian society. Those who stressed more about war or terrorist attacks tended to identify themselves more often as members of the Ukrainian community.

Figure 3. Factors of social identity in Ukraine

Notes: (*) refers to the statistical significance in the difference of means between the two groups of respondents. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Overall, my results confirm that identities are multiple and follow a specific formation mechanism. However, common for them is that they are all influenced by political values and preferences in the case of Ukraine. Those who see Ukraine as a democratic country tend to more often identify themselves as belonging to the Ukrainian nation, state, or society. Those who lean more to the West (proxied by the EU) are more likely to feel Ukrainians or citizens of Ukraine. Also, individuals with confidence in the national government more often choose to belong to Ukraine, viewed either as a nation or the society. These associations are logical since Ukraine as a country, state, and nation displays well-structured and formulated preferences for a Western type of development, democratic forms of governance, and freedom for its citizens. Hence, everyone who values these choices goes with Ukraine either as a member of ethnos, community or a citizen!

References

Aliyev, H. (2019). The Logic of Ethnic Responsibility and Progovernment Mobilization in East Ukraine Conflict. Comparative Political Studies, 52(8), 1200–1231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830730

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2012). The standard ingroup identity model. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 439–457). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n48

Hale, H. E. (2004). Explaining Ethnicity. Comparative Political Studies, 37(4), 458–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003262906

Kulyk, V. (2018) Shedding Russianness, recasting Ukrainianness: the post-Euromaidan dynamics of ethnonational identifications in Ukraine. Post-Soviet Affairs, 34(2-3), 119-138. DOI: 10.1080/1060586X.2018.1451232

Kuzio, T. (2000) Nationalism in Ukraine: Towards a New Framework. Politics, 20(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.00115

Sasse, G., & Lackner, A. (2018) War and identity: the case of the Donbas in Ukraine. Post-Soviet Affairs, 34(2-3), 139-157. DOI: 10.1080/1060586X.2018.1452209

Table 1. Percentage of respondents answering positively to the selected questions, by identity types

| Yes | No | T-test for the difference in means | ||

| Differences | t-value | |||

| Feels a Ukrainian | ||||

| Born in the country | 0.97 | 0.59 | 0.38*** | 12.205 |

| Speaks Ukrainian at home | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.59*** | 15.170 |

| Confidence in the government | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.11*** | 2.878 |

| Ukraine is democratic | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.13*** | 3.202 |

| Confidence in the EU | 0.54 | 0.30 | 0.24*** | 3.860 |

| A good political system should have experts making decisions | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.09*** | 2.785 |

| A good political system can have the army rule | 0.1 | 0.22 | -0.12*** | 2.621 |

| A good political system needs democracy | 0.83 | 0.76 | 0.07** | 2.180 |

| Worries about a foreign invasion | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0 | 0.398 |

| Worries about a terrorist attack | 0.84 | 0.87 | -0.03 | -0.790 |

| Feels citizen of Ukraine | ||||

| Born in the country | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.04** | 2.217 |

| Speaks Ukrainian at home | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.16*** | 4.435 |

| Confidence in the government | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.030 |

| Ukraine is democratic | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.503 |

| Confidence in the EU | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.12*** | 5.132 |

| A good political system should have experts making decisions | 0.45 | 0.51 | -0.06 | -1.234 |

| A good political system can have the army rule | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 1.022 |

| A good political system needs democracy | 0.84 | 0.72 | 0.12*** | 3.274 |

| Worries about a foreign invasion | 0.95 | 0.81 | 0.14*** | 6.930 |

| Worries about a terrorist attack | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.11*** | 3.766 |

| Feel a member of my community | ||||

| Born in the country | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.03 | 1.811 |

| Speaks Ukrainian at home | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.15*** | 3.359 |

| Confidence in the government | 0.19 | 0.25 | -0.06** | -2.050 |

| Ukraine is democratic | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.05** | 2.306 |

| Confidence in the EU | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 1.904 |

| A good political system should have experts making decisions | 0.45 | 0.50 | -0.05 | -0.829 |

| A good political system can have the army rule | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 1.263 |

| A good political system needs democracy | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.05 | 1.300 |

| Worries about a foreign invasion | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.07*** | 2.681 |

| Worries about a terrorist attack | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.09*** | 3.273 |

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations