25 years later Russia’s relations with the West are in crisis. The broad picture is disturbing – while NATO is expanding its presence in Eastern Europe, puts more resourses to build the capacities, and changes the strategy from “reassurance through surge” to a forward defense deterrence strategy – Russia is increasing military cooperation with many of the West’s geopolitical challengers, and continues efforts to undermine the EU project and put herself as powerful opponent of the Western liberal hegemony. For Ukraine, neither Minsk II, nor Minsk I are not leading to the resolution of the conflict in the East – at best, we can achieve a stable frozen conflict – writes Edward Walker from UC Berkley. And the Western support – resembling the frog and the boiling water strategy – may eventually provoke even more irrational and unpredictable actions from Russia.

Following is an expanded and updated version of a talk I gave at the 39th Annual Berkeley-Stanford Conference on March 6, 2015. The conference title was “The Collapse after a Quarter Century: What Have We Learned About Communism and Democracy?”

The title of the talk I was going to give today was “Mishandling Russia.” However, last week a recent Berkeley political science Ph.D., Andrei Krikovic, now an assistant professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, gave what I thought was an excellent talk entitled “The Ukraine Crisis and the New Cold War: The View From Moscow,” in which he made many of the points I was going to make. We also have a talk scheduled for Monday by Masha Lipman, one of Moscow’s most prominent political analysts, entitled “From a Model of Development to Evil Incarnate: How Russia Has Come to Loathe the West.” So rather than repeating their arguments, I thought I would address one answer to the question in the conference title as follows: One thing that we know for sure 25 years later is that Russia’s relations with the West are in crisis. And I don’t see a clear path forward for resolving that crisis in the foreseeable future.

I’m going to focus on the security dimension of the current drama, which I think is the heart of the matter and the reason why it is so dangerous. First, however, let me begin with a quick update on the war in eastern Ukraine.

Update on the war in eastern Ukraine

The agreement reached last month in Minsk (“Minsk II”) was supposed to bring an end to the fighting and serve as the basis for a political settlement in eastern. It provided for a ceasefire, a withdrawal of heavy weapons from the line of contact (see the red line in Slide 3), and other measures that were to follow.

The agreement has succeeded in reducing the level of violence in eastern Ukraine (as did Minsk I initially), but there is still some fighting, mostly in the form of artillery, rocket, and mortar fire, to the north and northwest of Luhansk, to the west and northwest of Donetsk, and to the east of Mariupol. There is also clear evidence of a continuing flow of irregulars and military supplies from Russia, while the Ukrainian government claims, and Western intelligence services confirm, that there are still many Russian regular troops in the conflict zone.

Finally, there have been worrisome reports recently of a buildup of Russian forces along Russia’s border with Ukraine, particularly in Belgorod, which is about a one hour drive north of Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest city.

Nonetheless, on balance I believe there is a reasonable chance that a genuine ceasefire will eventually come into effect, but that will probably only happen after the separatists achieve some immediate military objectives, including retaking the town of Shyrokyne to the east of Mariupol and driving Ukrainian forces out of Pisky and perhaps other areas to the west and northwest of Donetsk.

There is also a chance that we will get – more-or-less – a withdrawal of heavy weapons from the line of contact, although confirming that will be very difficult if not impossible for OSCE monitors.

If we do get a genuine ceasefire and a significant drawback of heavy weapons, it is possible that we will then get a stable frozen conflict in eastern Ukraine, which I have been arguing for months is the least-worst outcome. For that to happen, there will have to be a follow-on agreement to drawback more than just heavy weapons from the line of contact, and probably also an agreement to establish a buffer zone patrolled by an armed peacekeeping force that, under the circumstances, will almost certainly have to include a Russian contingent.

There is, however, very little chance that any of the other provisions in Minsk II will be implemented, which should be kept in mind when you hear Western officials insist that sanctions will be lifted only if and when Moscow implements the Minsk Agreements in full – that is not going to happen, any more than the Russians are going to withdraw from Crimea.

That said, my view is that the least unlikely outcome is an unstable (or if you prefer, not quite frozen) conflict in the coming months, one where fighting continues at various points along the line of engagement but without major, or at least rapid, changes in territory.

The reason I doubt we will see a stable frozen conflict is that the breakaway region of “Novorossiya” will not achieve Moscow’s strategic objectives in Ukraine, which are to prevent it from joining the West and ensure that it remains a buffer zone between Russia and NATO. Moreover, it will saddle Moscow with the burden of trying to restore the region’s shattered economy and social order.

So a stable frozen conflict – one with a broad separation of forces (not just heavy weapons) monitored by the OSCE, and perhaps even the establishment of a buffer zone patrolled by an armed international peacekeeping force, as in Transnistria – strikes me as unlikely. Rather more likely is that the ceasefire breaks down completely once again. And it is also very possible that the Kremlin will openly introduce Russian forces into the conflict zone.

If it does, or if the ceasefire breaks down and we see, for example, a separatist assault on Mariupol, I am convinced that the United States and other Western governments will ramp up military assistance to Ukraine and start providing Kyiv with lethal weapons. Is so, I think the likely outcome will be a full-blown proxy war between Russia and the United States, which will be supported by most but not all of its NATO allies. Indeed, a decision by Washington to provide military assistance, and the increased risks of escalation in Ukraine and even war with Russia, will likely strain the alliance, particularly if Washington gets out too far ahead of Germany and France.

If we do get into a proxy war, it will be a proxy war between the world’s two nuclear superpowers, one that neither side will be willing to lose. If anyone can tell me how that can turn out well, especially for Ukraine, I am all ears.

Reinforcing NATO’s eastern defenses

So what of the broader security aspects of the Ukraine crisis? Let me focus first on NATO’s efforts to build up its eastern flank defenses, and then turn to the debate over Western military assistance to Ukraine.

NATO began, more-or-less quietly, to reinforce its eastern defenses almost immediately after Russia’s occupation and annexation of Crimea in February. Those measures were then formalized and expanded upon at the NATO Wales summit in September. NATO has beefed up its air and naval assets in the Black Sea and Baltic Sea; increased the size of its rotational forces on its eastern flank and made them more or less permanent (that is, they are constantly rotating in and out, albeit without permanent bases, at least so far); increased the frequency and scale of military exercises in, and training for, the frontline states; increased other forms of military assistance to those states; and pre-positioned military hardware and improved logistical facilities along NATO’s eastern borders.

Additionally, it was agreed at Wales that the alliance would establish a new rapid reaction force, to be called the NATO Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF) to supplement its existing Rapid Reaction Force (RRF), which was inaugurated in 2003. The VJTF, which is scheduled to be operational by the end of the year, is to consist eventually of some 5,000 troops, including air, naval, and special operations units, some of which are to be deployable in 2-3 days. Eventually, the force will be spearheaded by a rotating lead nation (either France, Germany, Poland, Spain, or the U.K.). An interim VJTF has been established in the meanwhile, with troop contributions from Germany, Norway and the Netherlands. The VJTF will bring rapid reaction forces in Europe assigned to NATO up to some 30,000 troops.

Finally, it was agreed at Wales that the alliance as a whole would increase defense spending. However, given the economic stress and austerity measures in place in much of the EU, that commitment is rather less than firm. The declaration affirmed that members spending less than 2% of GDP on defense in total, and less than 20% of that on hardware, would reach those targets within a decade, but only “as growth improves.” So don’t hold your breath.

Still, military spending overall is likely to increase in the coming years, especially if the EU economies begin to perform better. Outside the United States, spending has been going down for years (across the alliance it decreased by around 1% in 2014 despite the Ukraine crisis). That will probably reverse itself, albeit slowly, unless there is an actual military clash with Russia, in which case spending will doubtless rise very rapidly. (Keep in mind that Western economies are some 20 times larger than Russia’s, and Western military spending overall likewise dwarfs Russia’s.)

NATO’s overall military strategy is suggested by the next slide. In January, NATO announced plans to establish “NATO force integration units” (NFIUs) in the six eastern flank countries – Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Bulgaria.

These command organizations, which are to become operational next year, are not large – they will have only some 50 permanent staff. They are to be tasked with planning and coordination only, including overseeing regular exercises and training efforts of the VJTF and other NATO operations in their host countries. I suspect that they will also eventually coordinate exercises and training in nearby non-NATO countries, notably in Ukraine and Georgia. Most importantly, the NFIUs will be permanent on-site command structures for facilitating any surges to the east in the event of a crisis, particularly the dispatching of NATO’s rapid reaction forces. Also, note that they are not being deployed on a “rotational” basis, and as such they may prove to be the first of many permanent NATO forces based near the alliance’s eastern borders.

Indeed, there are growing calls for NATO to change direction, presumably gradually, and to move from what might be called a “reassurance through surge” strategy to a forward defense deterrence strategy with permanent basing, much like NATO’s strategy for defending Europe during the Cold War. General Philip Breedlove, Commander of U.S. Forces in Europe, put the argument as follows in testimony before the House Armed Services Committee on February 5:

A temporary surge in rotational presence, for example, will not have lasting effect unless it is followed by the development and fielding of credible and persistent deterrent capabilities. Forward deployed air, land, and sea capabilities permits the U.S. to respond within hours versus days as crises emerge. We must follow our near-term measures with medium-term efforts to adapt the capabilities and posture of United States, NATO, Allies, and partners to meeting these new challenges. We must accelerate this adaptation because we now face urgent threats instead of the peacetime environment previously anticipated.

Advocates of a forward defense/deterrence strategy argue that a surge approach is inherently destabilizing because rapid reaction forces can be deployed to the east only after a crisis has broken out, at which point it may be too late to deter Russian aggression. Moreover, surging can raise the risk of war by increasing incentives to preempt before those forces are fully in place. There is additionally the tricky question of who gets to decide when rapid reaction forces are deployed, and under what circumstances. That can undermine the effectiveness of a surge strategy as a deterrent if, for example, the Kremlin gambled that political divisions in Western alliance would prevent or significantly delay deployment.

In addition to measures being taken by the alliance as a whole, individual member states have been improving their national rapid reaction capabilities and have been increasing military assistance to the eastern flank countries. For example, a new multinational rapid reaction force, the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), is to be in place before 2018, made up of troops from the U.K., Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Norway. Presumably the idea is that Britain and other less-dovish West European countries want a rapid reaction capability that cannot be vetoed by more-dovish NATO allies. Individual NATO countries have also been increasing military cooperation with, and assistance to, the frontline countries on a bilateral basis.

In addition to measures being taken by the alliance as a whole, individual member states have been improving their national rapid reaction capabilities and have been increasing military assistance to the eastern flank countries. For example, a new multinational rapid reaction force, the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), is to be in place before 2018, made up of troops from the U.K., Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Norway. Presumably the idea is that Britain and other less-dovish West European countries want a rapid reaction capability that cannot be vetoed by more-dovish NATO allies. Individual NATO countries have also been increasing military cooperation with, and assistance to, the frontline countries on a bilateral basis.

Finally, it is worth noting that Finland and Sweden have been taking steps to increase their defense capabilities and to cooperate more extensively with NATO. They have been particularly concerned about defending strategically important islands in the Baltic Sea. Last week, Sweden announced that it planned to station 150 troops on the island of Gotland after a decade’s absence.

The growing U.S. military presence in the eastern flank countries

Doubtless of greatest concern to Moscow, however, are the measures the United States has been taking to increase its presence, and its ability to project power, to the east. The Defense Department has labeled its response to the Ukraine crisis “Operation Atlantic Resolve” (“OAR”), and recently it announced that it was dividing OAR into Atlantic Resolve North (which has been the priority theater and includes the Baltic states and Poland) and Atlantic Resolve South (initially Romania and Bulgaria, but possibly other countries in the future such as Hungary and the Czech Republic).

To date, OAR has consisted primarily of continuous U.S. military exercises by “rotational” troops in the eastern flank countries. The DoD posts regular briefings on the number and nature of these exercises, which have been extensive and growing, on its OAR site.

Probably the most provocative of these exercises for Moscow will take place in May, when some 3,000 troops from the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division will conduct exercises in Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. Some 750 U.S. military vehicles and pieces of heavy equipment, including tanks, IFVs, artillery pieces, and helicopters, will be involved, much of which has already been unloaded in Riga. The deployment is slated to end in June, at which point the troops involved are expected to return to the U.S. The Pentagon recently announced, however, that the force’s rolling stock, including tanks, IFVs, and armored personnel carriers, will remain in the European theater, apparently in Germany.

That said, if relations with Moscow worsen, or if Russia announces large scale exercises near the border with Estonia and Latvia in, say July, I would not be surprised to see the 3rd Division troops remain in place, at least until an equally large and potent force is rotated in to replace them.

As this suggests, another major component of OAR has been the prepositioning of significant quantities of U.S. military hardware, including tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and other armor in the eastern flank countries. My understanding is that the Pentagon plans to have prepositioned at least 150 tanks and IFVs in Poland and the Baltic states by the end of the year. Again, I would not be surprised if the amount of prepositioned armor did not get ratcheted up in the coming months and years, given the costs and time required to move heavy equipment to Europe from the United States. The DoD is also increasing aviation assets in Europe, including the reintroduction of A-10 Thunderbolt “tank buster” jets to the theater.

I should note that the 3rd Division troops are replacing a smaller force from the Army’s 2nd Cavalry Regiment, which is permanently based in Germany. The regiment, with its Stryker fighting vehicles, has been exercising regularly in Poland and the Baltic states since January. Last month, the unit participated in a parade celebrating Estonia’s independence day in Narva, some 300 yards from the Estonian-Russian border (a fact stressed by media coverage of the event, particularly in Russia). Narva is a predominately Russian-speaking region (some 90% of its inhabitants are Russian speakers, and around 80% are ethnic Russians, much higher than equivalent figures in the Donbas). It is also an area where there are still unresolved border disputes between Estonia and Russia. That said, it is also true that the local inhabitants seemed to welcome U.S. participation in the parade.

Nonetheless, there can be no doubt that the Kremlin will view a U.S. military parade in a Russian-speaking region 300 yards from its border as highly provocative.

Increased Western military assistance to Georgia

Just a quick word about another potential hotspot – Georgia. At its Wales summit, NATO agreed to a “Substantial NATO-Georgia Package” that was to include “enhanced cooperation” on military matters. The nature of that cooperation was to be determined by a delegation that would assess Georgia’s defense needs.

In the period since, NATO has announced it is establishing a “Defense Capacity Building Team” for Georgia as well as a “NATO-Georgia Joint Training and Evaluation Center” and a “Defense Institution Building School” in Georgia.

The stated purpose of these initiatives is to help train Georgian officers and assist with military reforms, as well as to facilitate military exercises with Georgian troops, particularly in-country. It is also clear that the intent of Western military assistance to Georgia has shifted from initial efforts to help restore internal order (e.g., reestablish Tbilisi’s sovereignty over the Pankisi Gorge region in the early 2000s), to international peacekeeping operations (notably Georgian participation in NATO’s operation in Afghanistan), and now to national territorial defense.

Most importantly for Moscow, NATO membership for Georgia also remains on the table, at least formally, as confirmed most recently at the summit of NATO defense ministers in early February, which produced a “Joint Statement of the NATO-Georgia Commission at the level of Defense Ministers.” After describing NATO military assistance to Georgia, the statement asserted that this assistance “will help Georgia advance in its preparations towards membership in the Alliance.” It continued:

Allied Ministers recalled the Wales Summit decisions, in particular that Georgia has made significant progress since the Bucharest Summit and has come closer to NATO by implementing ambitious reforms and making good use of the NGC [the NATO-Georgia Council – EWW] and the ANP [Annual National Program, which coordinates NATO-Georgia military cooperation – EWW]; and that Georgia’s relationship with the Alliance contains the tools necessary to continue moving Georgia forward towards eventual membership. NATO Ministers recalled the agreement of Heads of State and Government at the 2008 Bucharest Summit that Georgia will become a member of NATO, and reaffirmed all elements of that decision, as well as subsequent decisions.

This is not to say that I think NATO membership for Georgia is likely in the foreseeable future – I don’t. Accession requires formal approval from all NATO member-states, including difficult treaty ratification procedures in countries such as the United States. Moreover, given that Western countries consider Abkhazia and South Ossetia to be legally part of Georgia, and thus Russian troop presence in those regions to be illegal, NATO accession would put Georgia in a position to invoke Article 5, and effectively put NATO countries in a state of war with Russia.

I do not think there is any chance that Washington, let alone Berlin or Paris, would agree to Georgian accession to NATO under those circumstances, despite the bluster of many U.S. legislators.

But that is not how Moscow will see it.

Increased Western military assistance to Ukraine

Let me turn now to the debate over Western military assistance to Ukraine. Last year, the U.S. spent $118 million on non-lethal military assistance to Kyiv. It is difficult to sort out just how much of that assistance has been disbursed already, and whether those funds are separate from, or overlap with, commitments made this year. But as best as I can tell, the Obama administration is planning to provide at least $130 million more in non-lethal military assistance in 2015.

To date, the types of equipment provided (or to be provided) include secure communication equipment, counter-mortar radars (I saw a report indicating that three U.S. counter-mortar radars were delivered last year, of which two have already been destroyed), Humvees, surveillance drones, body armor, helmets, night and thermal vision devices, heavy engineering equipment, patrol boats, so-called “meals-ready-eat” (MREs), tents, uniforms, and medical supplies.

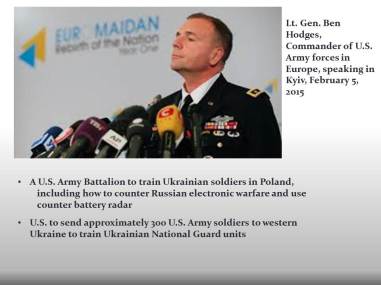

The U.S. is also continuing to help train Ukrainian forces. (The U.S. has been providing limited training assistance to, and carrying out occasional exercises with, the Ukrainian military for years.) Until recently, that training took place mostly abroad. In early February, however, Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, commander of U.S. Army Forces in Europe, gave a press conference in Kyiv during which he confirmed that a U.S. Army battalion – around 300 solders – was being sent to western Ukraine to train Ukrainian national guard units, including instruction on how to counter Russian electronic warfare equipment and use counter-motar radars. The Brits, who recently provided Ukraine with lightly armored “Saxon” personnel carriers, also announced recently that they are sending 75 military instructors to Ukraine, while Poland, which has been training Ukrainian military instructors in Poland, will send 33. And there are reports that Georgia and Israel are helping train Ukrainian troops as well.

The U.S. is also continuing to help train Ukrainian forces. (The U.S. has been providing limited training assistance to, and carrying out occasional exercises with, the Ukrainian military for years.) Until recently, that training took place mostly abroad. In early February, however, Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, commander of U.S. Army Forces in Europe, gave a press conference in Kyiv during which he confirmed that a U.S. Army battalion – around 300 solders – was being sent to western Ukraine to train Ukrainian national guard units, including instruction on how to counter Russian electronic warfare equipment and use counter-motar radars. The Brits, who recently provided Ukraine with lightly armored “Saxon” personnel carriers, also announced recently that they are sending 75 military instructors to Ukraine, while Poland, which has been training Ukrainian military instructors in Poland, will send 33. And there are reports that Georgia and Israel are helping train Ukrainian troops as well.

The key debate in Washington, however, is over whether to increase military assistance to Kyiv significantly, and in particular whether to provide Kyiv with so-called defensive lethal equipment, notably Javelin man-portable anti-tank missiles.

Late last year Congress passed, and the president signed, the Ukraine Freedom Support Act, which among other measures authorizes the administration to provide additional military assistance, including lethal weapons, to Ukraine at its discretion. Congressional hawks from both sides of the aisle have been pressing the administration to exercise that discretion. Some have also advocated designating Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova “major non-NATO allies” (not a status with real legal significance, but meaningful nonetheless because it would make compromise with Russia all the more difficult).

Recently, prominent officials in the Obama administration have also begun expressing support for arming Ukraine, including the new Secretary of Defense, Ashton Carter, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Martin Dempsey, and James Clapper, the director of national intelligence. My understanding, however, is that their position is that lethal assistance should be provided only if Minsk II breaks down and the war in eastern Ukraine ratchets up significantly.

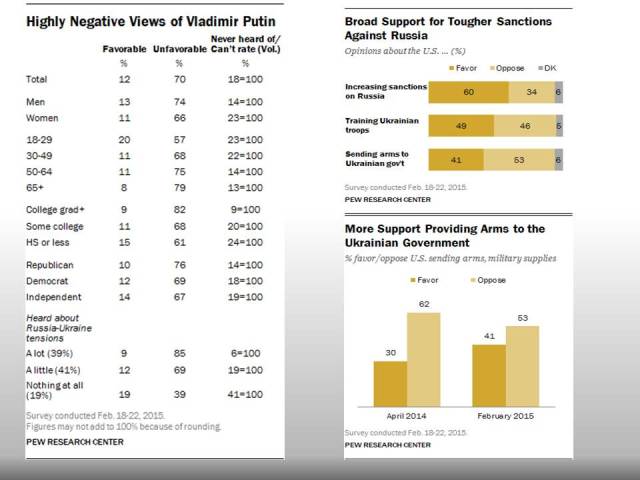

Finally, as suggested in the next slide, U.S. public support for lethal assistance to Ukraine has also been growing, although more (53%) still oppose it than support it (41%).

To date, the White House has decided against lethal assistance to Ukraine, reportedly because the president does not believe it would make an appreciable difference on the battlefield for months, if ever, and also because he fears that doing so would be the death knell of Minsk II, might provoke a renewed offensive by the separatists, and might even lead to an open invasion by Russia. I suspect the White House plans to help Ukraine defend itself more effectively in the coming years, but only after a stabilization of the conflict in eastern Ukraine. But if the separatists renew their offensive, or if Russia becomes openly involved in the fighting, it is highly likely Washington will ramp up military assistance to Ukraine rapidly and significantly.

It is also important to appreciate that there are many ways for Washington and its allies to help Ukraine militarily other than by openly providing U.S. weapons. They are already, as noted, helping train Ukrainian soldiers. Moreover, financial assistance in general makes it easier for Kyiv to fund its very expensive military operations. Nor is there a U.N. ban on selling weapons to Kyiv, which means financial assistance can put Ukraine in a position to purchase supplies and equipment abroad, including lethal weapons.

At some point the United States might also undertake a covert operation, or at least one with “plausible deniability,” whereby Ukraine is helped to buy surplus Warsaw Pact hardware from Poland, Romania, and perhaps other central European neighbors. While Russian intelligence would certainly become aware of the operation, and doubtless bloggers would pick it up as well, the U.S. position would be, “You pretend not to help the separatists, and we pretend not to help Kyiv.”

The frog and the boiling water

I’m sure you’re familiar with the perhaps apocryphal claim that if you put a frog in a pot of water and bring the water to a boil rapidly, the frog will realize it’s in trouble and jump out. However, if you bring the water to a boil slowly, the frog will stay put and boil to death. My sense is that the administration is taking a “frog in the boiling water” approach in its military response to the Ukraine crisis. It wants to “reassure” its European allies, but it does not want to cross a redline with Moscow. To that end, it has been building up, and will continue to build up, its presence in the east, and it has been providing, and will continue to provide, military assistance to Ukraine. But it has been doing so gradually, without too much fanfare, in the hopes that the Russian frog won’t jump out of the pot and bite it or its allies (assuming frogs had teeth, that is).

Specifically, the White House’s strategy has been to build up its forces on NATO’s eastern flank, particularly in Estonia and Latvia, so as to remove any doubt that Moscow would find itself at war with the United States if it invaded a NATO ally. NATO’s hard power deterrence in the Baltic states was minimal, in my view, when the crisis broke out last year, but I believe that is no longer the case. On balance, the U.S. deterrence force is probably sufficient at this point to make a Russia-NATO conflict in the Baltics less likely than it would have been otherwise. It also doubtless gives U.S. military planners more confidence that Moscow’s military options will be limited if Minsk II breaks down, the U.S. increases military assistance to Kyiv, and we end up in a proxy war in Ukraine or witness a full Russian invasion.

Nonetheless, the risk is that the already very angry Russian frog is going to jump out of the pot and do something “irrational,” like precipitate a war with NATO, or more likely take “rational” countermeasures elsewhere that the United States and its European allies find truly unpleasant, including but not only in Ukraine. Moreover, Moscow has a very considerable incentive to at least appear irrational and risk tolerant, which can be a self-fulfilling exercise.

To date, Moscow’s military response, aside from its actions in Ukraine, has been to continue, despite increasing budgetary constraints, its very expensive military buildup. It has also greatly increased the number and scale of its own military exercises, including in sensitive areas like the Baltic region, the Black Sea, and the Arctic Sea. And it has been engaging in many forms of military brinksmanship, including dispatching Bear bombers into the English Channel, having attack jets buzz U.S. naval vessels, and sending military aviation, with transponders off, into western commercial air corridors.

Moscow has also announced that, after suspending its participation in the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) treaty in 2007, it is withdrawing from the agreement completely. And it has suggested that it may soon withdraw from the INF treaty as well, and then deploy new nuclear weapons systems targeting Western Europe or introduce nuclear weapons, including nuclear-armed Iskander ballistic missiles, into Crimea and Kaliningrad.

Finally, Moscow has been increasing military cooperation with many of the West’s geopolitical challengers, including China, North Korea, Venezuela, Cuba, and Syria, and it may do so at some point with Iran as well.

These, I should note, are only some of Moscow’s specifically military responses and options. It is also taking political, economic, and especially informational measures to promote divisions within the Atlantic Alliance, undermine the European project, and represent itself as the boldest, most powerful, and most effective global challenger to Western liberal hegemony.

Let me conclude, then, by saying that I do not see how we get out of this, and I am very worried. I have long thought that all parties would be better off if an agreement could be reached on some kind of non-aligned status for Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, and Azerbaijan, as well as a new agreement on conventional force dispositions. That seems very unlikely, at least for the time being, given political dynamics in both Moscow and the West.

At any rate, I hope I have made you as worried as I am.

An article was initially published on eurasiangeopolitics.com

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations