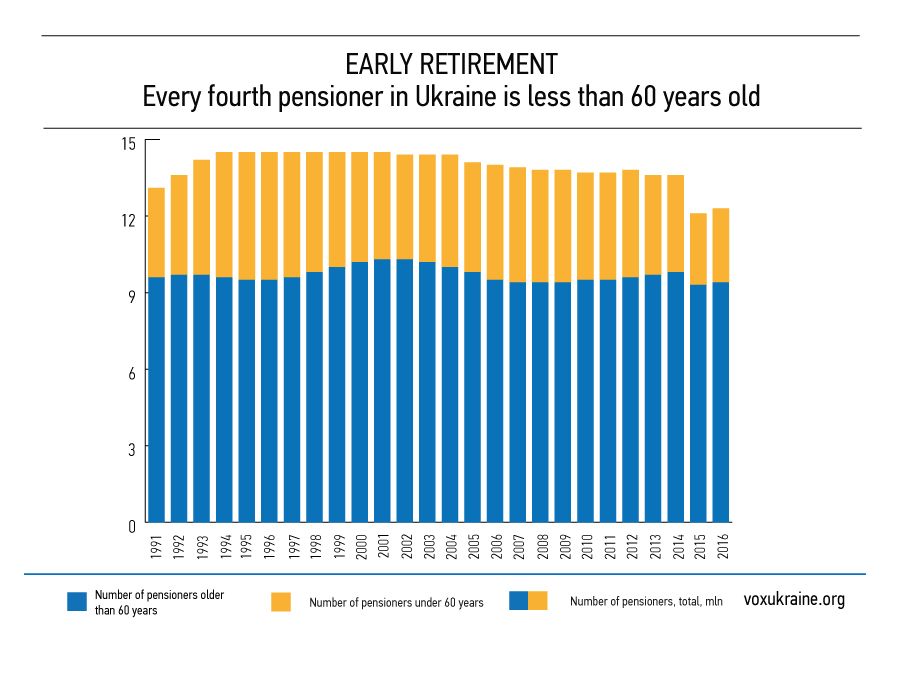

1. Gradual increase of the retirement age to 63 years for women and men

“[The increase of retirement age] is unacceptable from the social and demographic points of view, since the average life expectancy for males in Ukraine is 66 years only.”

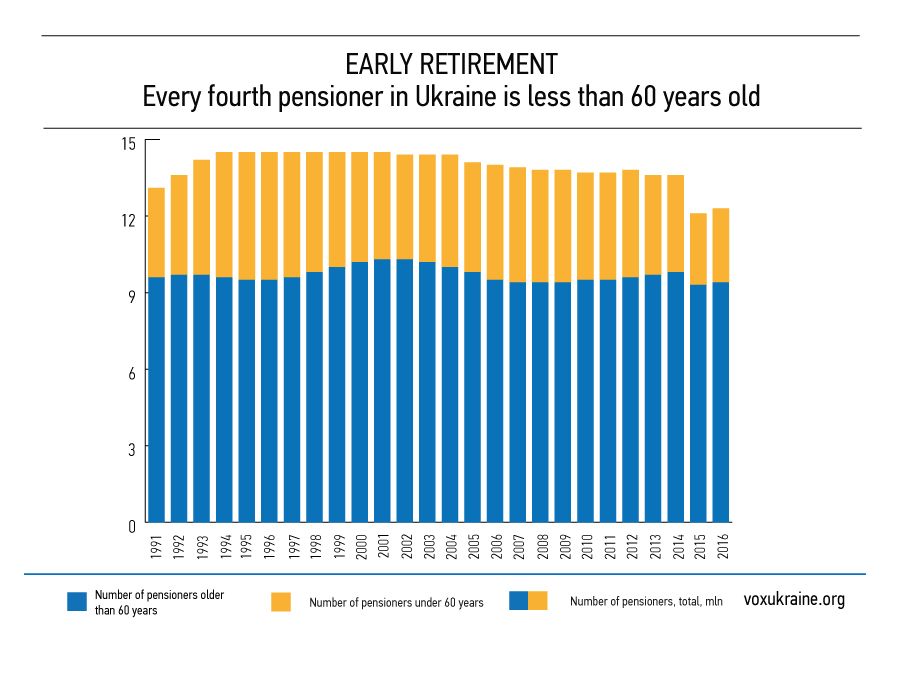

It’s true that the average life expectancy in Ukraine is lower than in most developed countries. However, what matters isn’t just the absolute retirement age, but also the average life expectancy at the time of retirement and early retirement. Ukrainian women hold one of the highest places in the world for life expectancy after retirement. In 2012, it was 23 years, hich, according to Ella Libanova, Director of the Institute for Demography and Social Studies, exceeds their average employment record. For men, the average life expectancy after of retirement is 14 years, which is comparable with the same figure for other countries. However, in Ukraine half f the male population retire at 60, and the rest — at 40. Thus, the average retirement age is 55 years. ’s one of the reasons why pension spending in Ukraine is among the world’s highest — 16% of GDP in 2013. In 2016, the Pension Fund deficit was 84,9 billion UAH, or approximately 4% of GDP. Meanwhile, the pensions remain small.

Read more

Read more

From the economic point of view, it’s important whether revenues and expenditures of the Pension Fund are balanced. Today, the Pension Fund income equals nly half of its spending on pensions, and there are four solutions to cut the deficit (see here for the effect of these methods):

- Cut the number of those who receive pensions

- Raise the number of those who pay contributions to the Pension Fund, and their payment discipline

- Raise contributions from employees

- Widen the gap between salaries and pensions.

Increasing the retirement age and cancelling early retirement benefits gradually reduce the Pension Fund deficit thanks to the first two solutions. The increase in rates paid means increase of the tax burden and contradicts the policy of recent years, when this burden has been reduced, in particular, to promote shifting salaries out of the shadow economy. Widening the gap between salaries and pensions means increasing relative poverty. Of course, a normal state can’t be interested in that, not mentioning the fact that it can lead to social tensions.

So, none of the four solutions to balance the pension system is popular. However, increasing the retirement age (solutions 1 and 2) is a long-term solution to the problem (which will take a lot of time) compared with solutions (3) and (4), which will have a temporary effect and a negative impact on the economy and society.

Lyashko’s statements about the need “to focus on de-shadowing of the economy, particularly employment, fighting unemployment, and reducing emigration, developing domestic industry and entrepreneurship, improving demographics, and increasing incomes of the citizens” are correct.

But let’s face the reality. De-shadowing of the economy requires certain measures, and it’s unlikely to happen without restoring confidence in fiscal and human rights protection authorities, as well as the judiciary. Examples abound. The radical, almost two-fold reduction of the unified social tax to 22% in 2016 hasn’t bring tangible results in de-shadowing of the wages.

Reducing unemployment is an important issue, but it won’t be able to significantly improve the financial performance of the Pension Fund, since the unemployment rate in Ukraine is not too high. According to the State Statistics based on the methodology of the International Labour Organisation, the unemployment rate in Ukraine in January-September 2016 was 9,2% or the population aged 15-70. It isn’t much higher than the historic minimum recorded in 2007-2008 (6.,4%), which can be considered as the lower limit of a "natural level” under the current institutional conditions. Reduction of unemployment from 9% to 6.5% will reduce the deficit of the Pension Fund only by 3-4% — hence, it won’t solve the problem.

In recent years, the number of emigrants was around 15-20 thousand people a year, or about 0.1% of the workforce. Moreover, in recent years Ukraine has seen a positive migration balance, i.e. more people come here than leave it. The situation with temporary labour migrants (so-called gastarbeiters) is a separate issue — the number of employees abroad depends not only on employment problems within the country, but also with opportunities to earn elsewhere. Labour migration is typical not only to Ukraine, but also to other Eastern European countries (Poland, Hungary, and the Baltic states), where the average salary is several times higher than in Ukraine, and the economy is much more developed. Labour migration has both negative and positive sides — for example, it decreases unemployment and creates inflow of cash into the country.

Improving demographics, i.e. increasing birth rate and reducing death rate, is a very slow process, difficult to influence by the public policy. Moreover, the only currently used tool aimed at increasing the birth rate are payments for newborns provided regardless of income. About 50% of the social assistance budget, which could be aimed at the vulnerable groups of population, is spent on it. The experience of many countries shows that this tool isn’t effective for a real increase in the birth rate, but only shifts in time the decision to have a child to be able to receive the benefits.

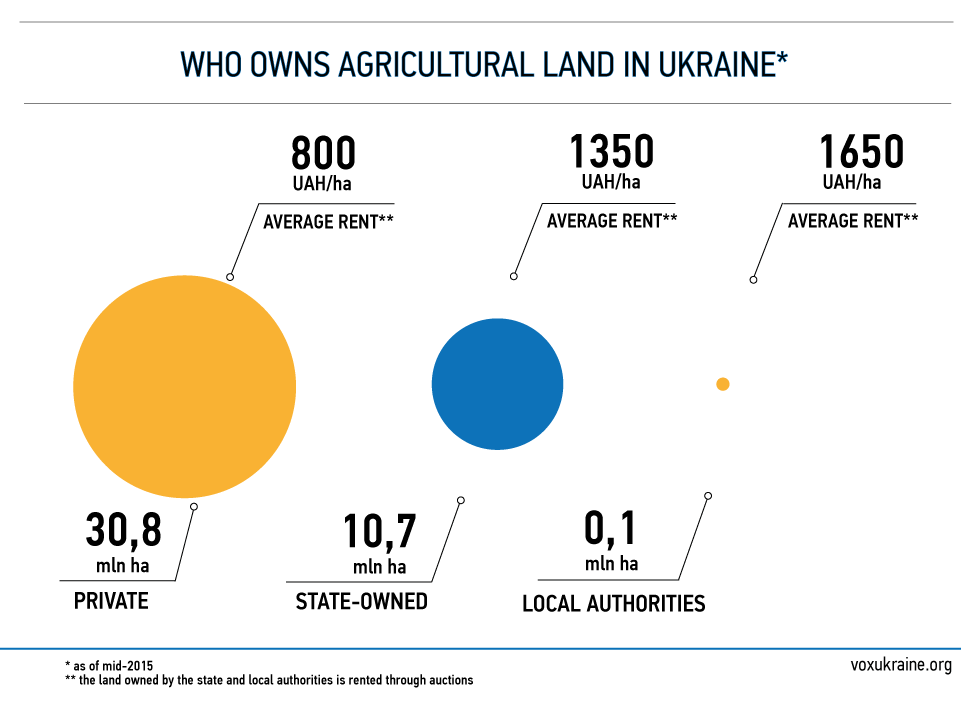

2. Moratorium on sale of agricultural land

Speaking against lifting the moratorium on sale of land, Lyashko threats with the danger of selling land for nothing “to foreigners and big landowners”. On the other hand, he provides data on the growth of agricultural output despite the moratorium.

First, agricultural land is not fundamentally different from other assets owned by many Ukrainian citizens, such as apartments. Why there’s no moratorium on sale of apartments? Moreover, even assuming the purchase of land by foreigners “for nothing” (now such purchases are forbidden by law), they will hardly move it out of the country, so the added value will be produced in the country. Furthermore, studies indicate that the main opponents of the sale are not owners of land shares, who should make such decisions. The experience of other countries with no restrictions on purchase of land by foreigners shows no dominance of foreign landowners.

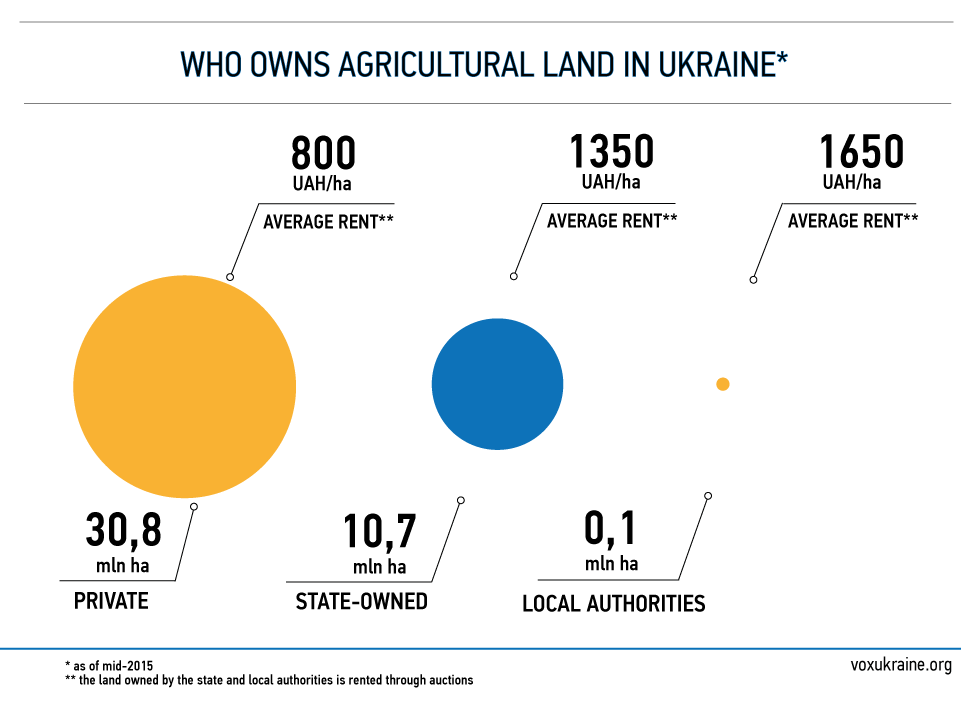

Picture 2. Who owns the land

Read more

Read more

The increase of crop yields since 2001 isn’t a consequence of the moratorium. First, in the 1990s, the land market didn’t exist. The moratorium preserved the status quo and didn’t significantly change the rules of the game. The event that led to the growth of agricultural production in the early 2000s was liberalisation of agricultural prices by Yushchenko’s government in 2000, which created economic incentives for producers. Second, productivity of various crops in Ukraine has almost doubled over the last decade (however, it is still 2-3 times lower than in Europe) despite the moratorium. Most likely, it would grow much faster if the land market emerged in the early 2000s — because in the market, assets are moving from less efficient to more efficient owners. However, existence of the moratorium and insecurity of land users prevent attracting new technologies and investments into production with high value added.

Finally, Lyashko repeats the eternal “crying of Yaroslavna” about decrease of the rural population and the need to support villages. To this we’d like to note that urbanisation is an objective process happening all over the world as new high-tech professions appear. That’s why trying to artificially “chain” people to the villages, for example, by depriving them of opportunities to sell their land share and receive “initial capital” to move to the city means leaving them in poverty — because the moratorium, among other things, doesn’t allow small farmers to obtain loans for development. The moratorium is causing a further decline of rural Ukraine because it limits the rents and revenues of the owners of land shares. Among the consequences there are low living standards, low demand for goods and services in the countryside, and limited capacity to create jobs in the countryside that would meet this demand.

3. Liberalisation of labour law

“The draft memorandum with the IMF refers to “removing restrictions in the Labour Code”, “limiting protected categories of employees”, “revision of the Labour Code to exclude strict rules”, and others.”

Explaining the unacceptability of such changes, Lyashko refers to the example of Britain in the early 19th century, where child labour was limited in cotton mills, which was the restriction of the free market. Comparing Britain 200 of years ago with modern Ukraine is incorrect. Britain moved from complete lack of restrictions in the labour market to introduction of the minimum restrictions. In Ukraine, the situation is quite the opposite — the labour market has been highly regulated since Soviet times (the Labour Code was adopted in 1972). Back then, the state was the sole employer, so instead of creating competition and improving working conditions it introduced more privileges for chosen categories of workers. The downside of this “super protection” of employees is unemployment (an employer won’t hire an employee who won’t be easy to fire in case of economic difficulties) and informal labour market — contract work or even verbal agreements — where workers are not protected at all. Moreover, due to the weak legal framework and total corruption in the judiciary, most restrictions of the Labour Code have no real effect.

In all socially oriented countries listed in Lyashko’s article (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland), labour law is much more liberal than in Ukraine. For example, they have no legally established minimum wage. They don’t have many other restrictions existing in our Labour Code, according to which it’s very difficult to fire an employee. However, the most important is that Ukraine shouldn’t be compared with developed countries with high income level, but with them at the time when their income level was comparable to the current Ukrainian one or to the countries with similar level of development.

4. Strict reduction of the budget deficit

The authors criticise reduction of the budget deficit at the level slightly higher than 2% of GDP, because it hinders soft fiscal and monetary policies. As an example, the authors refer to the US policy during the World War II when the significantly increased spending of the US government stimulated economic development.

Indeed, reducing public spending and deficit, at least in the short run, may reduce GDP. Negative effects of this decline were observed in Greece and were anticipated in Ukraine. That’s why today the IMF isn’t too strict on the possibility of temporarily high budget deficit during the recession, and much attention is paid to increase of spending efficiency rather than its technical reduction in all possible directions. The main problem in that it’s necessary to somehow finance the deficit.

There are two ways of financing a budget deficit — (a) selling state assets, i.e. privatisation, and (b) borrowing. We’ll discuss the first option below, in the section on privatisation.

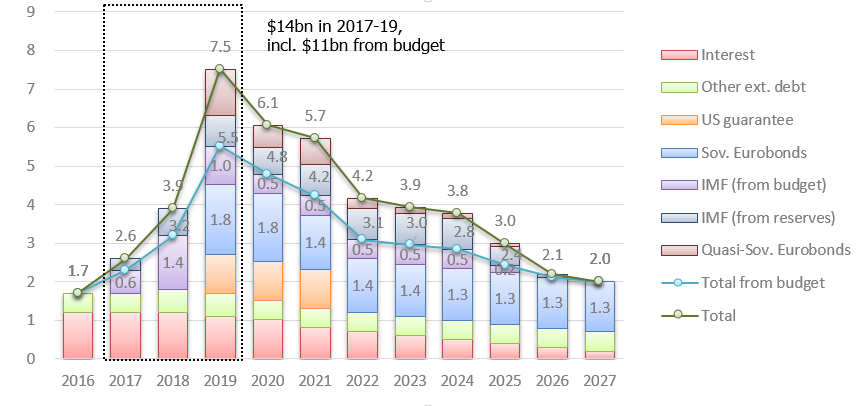

Read more

There are two types of borrowing, i.e. debt — external and internal. In 2014-2016, the country could borrow from external resources only through international financial organisations (including the IMF) or under the guarantees of other countries. Private investors don’t trust Ukraine, which is not surprising under current conditions, given the large amounts of debt (government spending on debt service is the second biggest budget item), the war in Eastern Ukraine, the problems of protection of property rights, and political instability. Internal borrowing, if done voluntarily, have the same problem: who will lend the government the money on reasonable terms? Indeed, deputies of the Verkhovna Rada don’t hold their savings in government securities.

Referring to the example of the US during the World War II is misleadingincorrect. During both wars, the First and the Second, the US showed growth of government spending to GDP ratio — to 23,8% in the first case and to 46,8% n the second. But it wasn’t the economy stimulation policy. The goal was winning the war at any cost — in both cases, the weight of defence spending in the state budget amounted to respectively 71.6% and 75.4%. For comparison, in 2016 defence spending in Ukraine accounted for 7% of total budget spending (2.7% of GDP).

The authors write that “when households lost the ability to fill the economy with money, and private investors stopped investing in the future, the state entered the playing field.” It’s not true. There households didn’t lose their consuming ability during the war — on the contrary, the US government restricted private consumption of goods such as petrol, clothing, and footwear to maintain military spending during the Second World War. In 1941, the US government restricted the sale of tires, in 1942 it stopped the sale of private cars, furniture, radios, fridges, and vacuum cleaners. It was possible to buy a new tube of toothpaste only upon return of the use tube. Does anyone want to impose such restrictions in Ukraine?

Figure 1. Military spending in total US budget spending in 1900-2016

Source: Usgovernmentspending.com

However, the authors say nothing about the need to tighten the belt to increase defence spending — they offer an indefinite increase of the budget deficit, in particular, to finance current spending. This means chronically large budget deficits and rapidly increase of the public debt despite its dangerously high level.

Lyashko offers to finance the growth of public spending by issuing medium-term government debt — development bonds, and force (!) the corporate sector and banks to buy them, which is a kind of expropriation of private funds. However, if we look at declarations of the Radical Party members, they are in no hurry to support the state by buying government bonds.

5. Inflation targeting

The authors raise two blocks of questions: first, whether it’s possible to achieve the proposed inflation rates (8%, 6%, and 5% in 2017-2019), and second, whether we really need such milestones — that is, whether low inflation will result in restraining economic growth.

Only time will answer the first question. It may be noted that even though in 2015 inflation was 43.3%, the National Bank managed to achieve its goal for 2016 — 12% (± 3 percentage points) — inflation rate was 12.4%. So, taking into account this experience, it’s possible to achieve results close to the goal (if there are no major negative shocks for the economy).

The second question is more complicated. Indeed, if prices grow faster than the target level, the NBU must limit money supply, which can lead to recession. A classic example are restrictions imposed by the Federal Reserve System headed by Paul Volcker in 1979-1983. In the 1970s, the average annual inflation in the US was 8.1%. To curb these lasting high inflation rates, the Federal Reserve System raised the federal funds rate to 20% in 1981. This led to the 1980-1982 recession, but after 1983 the annual inflation rate averaged 2.8% and never exceeded 5.4%. Such low inflation rate is a reason people in Ukraine and many other countries often prefer dollars to their national currency as a store of value. Moreover, there are many studies that indicate a positive impact of consistently low inflation on gross and direct investments, including foreign investments. Low inflation reduces uncertainty, extends the planning horizon, and allows for long-term investments.

Read more

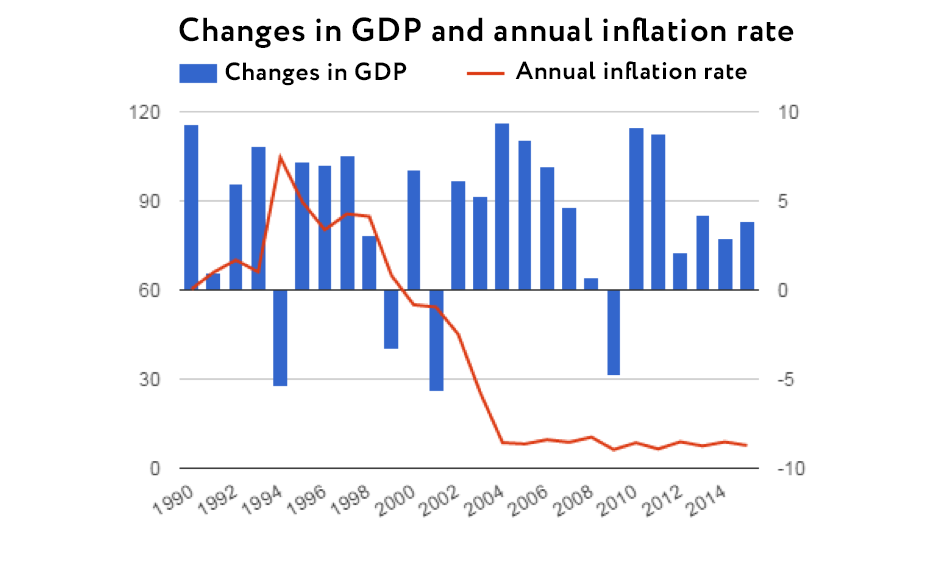

Many countries have had relatively high inflation and high rates of economic growth at the same time. However, is there a causal link? As examples, the authors mention Turkey in 2002-2006 and Poland in 1994-1997.

In Turkey in the 1990s, inflation was very significant, and GDP fluctuated greatly, so that the average growth between 1990 and 2001 was 3.4% per year. Only in the early 2000s, after inflation slowed down to less than 10% a year (2000 — 55%, 2001 — 54.2%, 2002 — 45.1%, 2003 — 25.3%, 2004-2015 — 8.3 %) Turkey saw a steady economic growth — the only decline was recorded during the 2008 global crisis.

Figure 2. Inflation increase and GDP growth in Turkey in 1990-2015

Source: IMF

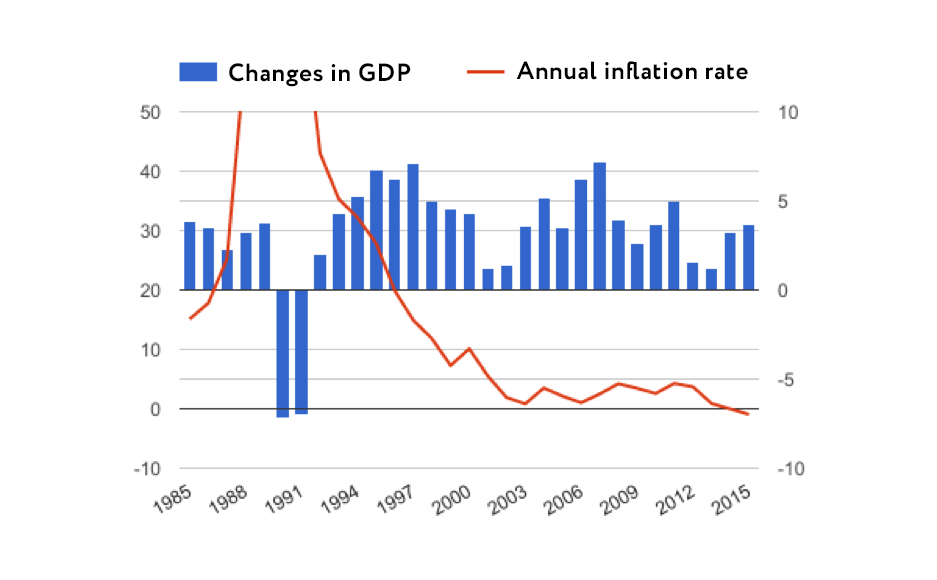

In Poland in the early 1990s, the situation was somewhat different — there was a transition from administrative command to market economy, which in the first stage, just like in Ukraine, caused a rapid rise in prices and economic decline through breakdown of the previous production chains. That’s why growth, which began in 1992, was partly due to the decline in the previous two years.

Even if we stick to the point of view of Grzegorz Kołodko (the Minister of Finance of Poland in 1994-1997, an author of The Polish Alternative), referred to by the authors, that the initial shock was excessive, and the growth mainly resulted from his programme, there are questions about the optimal strategy for Ukraine.

Kolodko writes that the main achievement of his government was the stable reduction of budget spending under conditions of moderate deficit. He believes that high rates of the National Bank of Poland caused damage to the economy. However, he considers them part of the general policy of the central bank, and refers to a quick disinflation from the levels of around 40% annually. In Poland in the mid-1990s, the central bank adhered to the strategy of gradual depreciation of the złoty (so-called Crawling peg) with simultaneous high discount rate, which contributed to a significant inflow of foreign investments that were redeemed in central bank reserves without proper sterilisation of the money supply. It was the primary source of inflation. Since 1998, Poland has been pursuing direct inflation targeting, and for most of this period, inflation has been less than 10%, which didn’t stop the economy from growing on average by 3.5% per year.

In Ukraine, we already see a substantial disinflation — reduction of the target from 12% in 2016 to 8% in 2017 is differs greatly from the disinflation attempts from the inflation levels of 40% per year. Second, we don’t have a significant investment flow from abroad or ties to the exchange rate as the main target. Thus, this year’s inflation target achievement does not require “draconian” measures that can lead to recession.

Figure 3. Inflation increase and GDP growth in Poland in 1985-2015

Source: IMF

According to the latest available publication of the Central Bank (January 2017), inflation forecast from the NBU is 9.1% (while the target is 8%), and the bank doesn’t intend to pursue tighter policy to reduce the forecast value.

Lyashko writes that the current “monetary policy of the National Bank “dries out” Ukrainian economy, making it a financial desert. “Financial depth” of the economy (the debt-to-GDP ratio) fell by one and a half — from 74% to 49%.”

However, causes of the fall of the debt-to-GDP ratio are the following:

- Rapid growth in nominal GDP due to inflation, while the volume of loans has changed less significantly

- Reduction of the amount of loans through write-offs and liquidation of banks

Moreover, this figure doesn’t take into account the quality of the loan portfolio. Loans to inefficient firms will lead to a technical increase of “financial depth”, but won’t benefit the economy. On the contrary, they can result in a banking crisis and affect depositors.

Ukraine doesn’t need a credit bubble, but creation of conditions for effective operation of the credit market. The most important conditions are a well-functioning judicial system and strengthening of protection of creditors’ rights, which will allow banks to be sure to obtain collateral in case of the debtor’s insolvency.

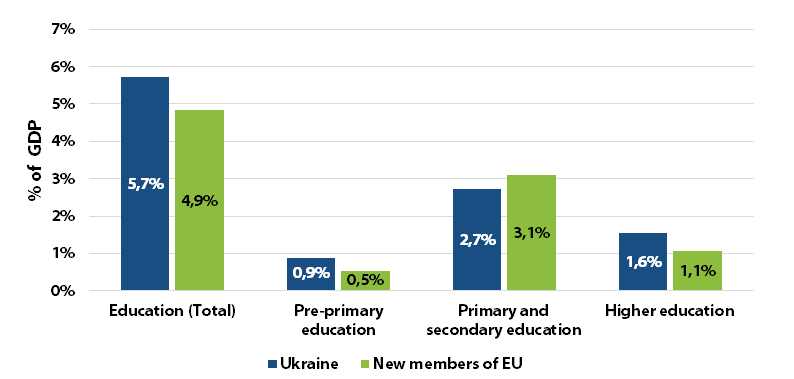

6. Education and healthcare reform

Describing a chapter of the IMF memorandum, which concerns reforms in medicine and education, Lyashko distorts statements, written in the Memorandum. In particular, he writes: “The IMF-Ukraine draft memorandum sets Ukraine’s obligations: “... we will speed up fiscal structural reforms, in particular, through healthcare and education reforms to reduce the size of the public sector.” In other words, the authorities promise austerity measures in medicine and education! Rather than rebuilding and developing them effectively, they will save on them. In fact, those who added it to the Memorandum are real mankurts!”

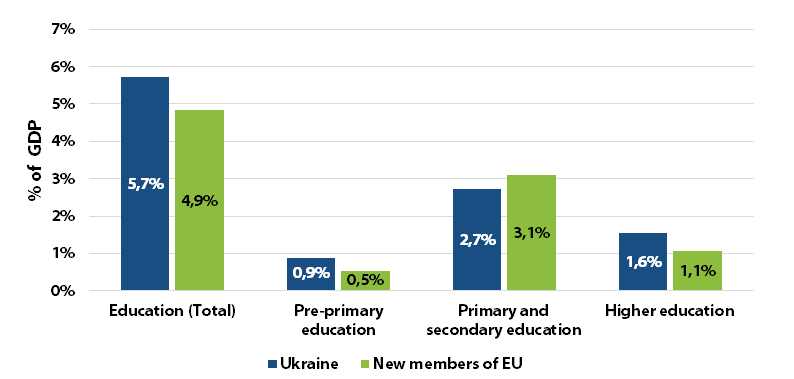

Figure 1. Expenditure on education in Ukraine and countries ─ new members of the European Union, the latest available data (Ukraine - 2016 *),% of GDP

Source: World Bank, State Treasury of Ukraine

Read more

The authors raise two questions from fundamentally different dimensions, trying to link them.

- Optimisation of public spending on education and healthcare

- Skills that must be provided by the education system.

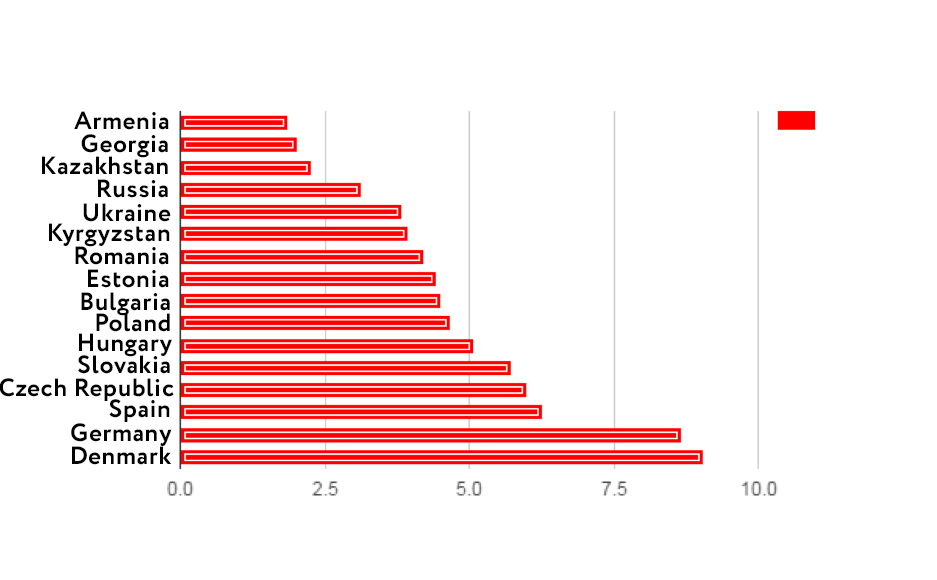

As for the first one, there’s certainly the need not to worsen, but preferably to improve the quality and availability of services provided by these sectors. When the authors refer to amount schedules of healthcare spending in different countries in dollars, they distort the perception of the situation, since they don’t take into account the size of the economies. It would be better to compare public spending as a percentage of GDP. According to this indicator, Ukraine is behind most EU countries, but ahead of several CIS countries (see the diagram below). If we take into account total spending (public + private estimated), Ukraine’s spending on healthcare as a share of GDP (7%) is higher than in a number of EU countries.

Figure 4. Public spending on healthcare as a percentage of GDP, 2013

Source: Database of the National Health Accounts of the WHO

Spending on education as % of GDP in Ukraine is higher (almost 6% of GDP) than average in the new EU member states.

The major problem with education and medicine is that Ukraine is a poor country, and can invest much less money (in absolute terms) into healthcare and education than more developed countries. But what’s even more important is that even small funds available are not spent in an efficient way because the country is “stuck in history”. Our medicine is largely based on the Soviet system of the 1930s, where the main problems were the fight against infectious diseases and preparing for reception of the wounded from a large-scale war. That’s why the number of hospital beds per 100 000 people in Ukraine is much higher than in the EU. Meanwhile, the main cause of death are cardiovascular diseases, prevention of which doesn’t need a lot of beds.

The situation in education is similar — decrease and aging of the population hasn’t led to a similar reduction in places in the middle or high schools. Therefore, just as in medicine, in education funds are spent on maintenance (heating, repairs, etc.) of a large number of outdated and unnecessary infrastructure rather than on things directly related to the quality of services — salaries of teachers and doctors, teaching supplies, or medical equipment, etc. Read more about optimisation of education here.

The second question — what, how, and when to teach, especially in primary and secondary schools, should be discussed with specialists — teachers and child psychologists. We are not experts in this field, that’s why we can only note is that it’s worth getting familiar with the best international practices. Today, Finland boasts the best primary and secondary education (for instance, according to PISA rating). There most classes are held outdoors and there’s no homework. Read more about the Finnish education system here and here.

7. Limiting the simplified tax system

The simplified tax system did greatly simplify rules of the game for micro and small businesses. However, there’s also a negative side — large companies started to use the simplified system to legally minimise tax, particularly in the retail, IT, and hospitality industries. If you look at the experience of other countries in support of small businesses, almost in all developed countries it is done through tax-filing simplification rather than a special tax status. If the goal is to preserve legal activities of micro and small businesses, it’s worth considering abolition of tax and tax-filing for businesses with small total revenue, as proposed in this article.

8. Export Credit Agency

An export credit agency (ECA) can become a key element of the export promotion system, provided it won’t simultaneously become a source of additional risks: fiscal, financial, corruption, and so on.

The law, adopted in late 2016, raises a lot of questions, which have already been raised in an issue of the Index for Monitoring Reforms (iMoRe). The key issues are (1) taking the newly established state institution to support exports out of the reach of the laws governing all other financial and insurance institutions in the Ukrainian market, (2) a rather peculiar structure of the institution’s governing bodies, and (3) selective support, which is provided only to a few sectors of economy. Another question is the compliance of the law with Ukraine’s international obligations.

In its current form, the law creates additional budget obligations and, therefore, risks, which the IMF can’t ignore while working with the country.

Read more

Interestingly, a manipulative infographic is used to support the new law on creation of an export-credit agency. In particular, the data on the Canadian ESA, Export Development Canada, features such numbers: +570 thousand jobs in 2013, which apparently must indicate the growing number of jobs in Canada to more than 0.5 million thanks to ESA. Even though Canada’s population is about 32 million, and such a jobs growth is quite strange. In fact, the report of the agency tells about the help to sustain such number of jobs rather than create them. Another interesting figure is +17% of exports per year. It seems that Canadian exports increase at such pace thanks to ECA. In fact, according to the agency's data, Canadian exports grew by 3.2% in 2013 (the year the infographic refers to).

Using performance indicators by Euler Hermes as an argument in favour of creation of a state institution to support exports is also surprising, because Euler Hermes is a private company that has been providing credit insurance services worldwide for over a century. In the middle of the last century, the company, together with the well-known accounting firm PWC, was chosen by the German Government as the service provider of export credit guarantees on behalf of the German Government. But this is only one aspect of activities of the company, which makes comparison of the business models of Euler Hermes and the newly created ECA in Ukraine wrong.

9. Industrial parks

Recently, VoxUkraine published the editorial board’s opinion on the Ukrainian version of “industrial parks”, which is actually another attempt to distort rules of the game and “optimise” taxation for certain companies, just as it has already been with the free economic zones and territories of priority development. In the world, the main advantage of these parks is the easy access to infrastructure. The tax benefits, if any, are linked to specific quantitative indicators, such as creation of a certain number of jobs.

10. Gas prices

Once again, Lyashko argues that domestically produced gas should be sold to the public at “domestic” prices. VoxUkraine has repeatedly explained (for instance, here and here), hy different gas prices for different categories of consumers and cross-subsidies are harmful to the economy. Let us remind you that in 2014 the deficit of Naftogaz exceeded the deficit of Ukraine’s state budget, and now it is reduced to almost zero. The next step of reforming the energy market must be monetisation of the “energy subsidies” so that consumers are motivated to save energy.

It’s wrong to assert that people should receive “state” gas at special low prices. All Ukrainian citizens are indirect co-owners of the Ukrgazvydobuvannya (UGV), but not all of them consume gas. Even those who directly consume gas, do so in very different amounts — usually large houses (mainly owned by people with high incomes) consume much more than small ones. That’s why setting low tariffs for everyone means to support of [the rich] gas consumers at the expense of the rest of society — because losses of public companies are funded at the expense of taxpayers.

11. Legalisation of gambling

Gambling ban didn’t lead to its disappearance. Just as the alcohol prohibition in the US or prohibition of prostitution and drugs doesn’t destroy the “bad habits”, but only creates a source of income for shady dealers. If the ban worked, we would hardly see news about the closure of gambling dens throughout Ukraine — from Odesa to Kryvyi Rih to Lysychansk.

From time to time, the government announces the fight against gambling, but with little success.

Is gambling addiction a real problem? Certainly. It’s even introduced into he International Classification of Diseases of the World Health Organisation under the code 63.0. This behavioural disorder should be treated, just like alcoholism. However, for some reason, the authors don’t advocate for a prohibition law. Perhaps because they are familiar with its negative consequences. Threats of transformation of Ukraine into a fashionable rookery for foreigners are groundless — before the gambling ban there were no gamblers’ queues on the borders with Ukraine, and they won’t appear even after its legalisation. Legalisation of gambling provides state regulation and greater responsibility of the subjects of this business, because in the case of abuse they might suffer financial losses. And, of course, it will fill the state budget, not someone’s pockets.

12. Privatisation

The authors argue that:

- Ukraine has no excess state property

- The sale isn’t well-timed

- There are many successful public companies in the world (with examples).

Let’s take a closer look at these statements.

First, the question of the optimal share of government in the economy is ambiguous and depends on many factors — history, important resources, public policy options, etc. Today, the share of state ownership in developed countries varies considerably. Moreover, its cost is often a non-trivial issue, especially when it comes to historic buildings or national parks. In France, for instance, each of the 96 cathedrals were valued at €1.

Read more

In recent years, especially after the global financial crisis of 2007-2009, the role of the state in the world economy has increased. Thus, the share of state enterprises in the Fortune Global 500 (the world’s largest enterprises in the world) increased from 9% in 2005 to 22% in 2014. This is due to two reasons — rescue of private companies through nationalisation (irrespective of the rating, PrivatBank is the latest, but not the only example in Ukraine) and growth of China’s economy, which remains a formally socialist country with a significant role of state ownership. However, the need for privatisation of the new assets is once again actively discussed in most developed economies.

It’s necessary to say a few words about the companies most often owned by the state in developed countries. These are primarily natural monopolies (telecom, railways), extraction and processing of natural resources (including power plants) and, more recently, financial institutions. Let us note that turbine manufacturer Kharkiv Turboatom, mentioned by the authors, doesn’t fall into any of these categories, which questions the need for state ownership. Such arguments as a large number of employees and amount of taxes paid should not be used if there’s no evidence the situation will worsen under private property. For example, after 2005, when Kryvorizhstal plant was privatised, it remained a major taxpayer (the 24th place in 2016 for total amount of taxes paid) and a large employer.

Second, as to the best time to sell state-owned companies — until clear criteria are not defined, you can always wait for a brighter future. However, the potential sale price may not only grow but fall. A striking example is Odesa Port Plant. In 2016, its starting price of about $530 million was considered too high — the auction didn’t take place. In 2009, there were offers to buy it for $600 million dollars. And it was only the declared offer, not the final price. Today, the enterprise doesn’t operate.

A major problem with state ownership, especially in developing countries, is corruption. We can list a bunch of corruption scandals that involved some of Ukraine’s state-owned enterprises — Ukrainian Railways, Ukroboronprom, Odessa Port Plant, Turboatom, seaports — the list goes on.

Therefore, it’s worth looking, on the one hand, on the purely economic feasibility of privatisation — whether the potential buyer can develop the business in comparison with the state (there are serious doubts on the effectiveness of Ukrainian state as an owner), on the other hand — at how important are privatisation revenues for the budget. As it was discussed above, today Ukraine is critically dependent on external financing of the budget, and in this case privatisation can be a good alternative.

Third, the authors refer to several successful state-owned enterprises, though they don’t provide criteria for their success, which complicates the analysis. Moreover, they conceal the fact that all these state-owned enterprises, except one, are partially privatised (see the Table below).

The UK and Germany privatised their postal services (the state’s share is 30% and 21% respectively). The top 10 telecom companies of the world — the clear majority — are private or with a minority stake of the state, despite the fact that 30 years ago almost all telecoms of the world were state-owned.

But the most important thing is that all these companies have been corporatised, and the government has no direct impact on their management decisions.

State participation in commercial industrial enterprises (such as Turboatom) in developed countries is usually the result of rescue of the company from bankruptcy through its political (not economic) inadmissibility — for example, in 2009, the state temporarily purchased shares of General Motors with subsequent sale of these shares in 2013. French company Renault was nationalised in 1945 because its owner had been accused of collaboration with the occupation regime during World War II. The company was privatised in 1996 (the state still owned 15% of the shares, which was temporarily increased to 19.73% in 2015). The sale allowed the company to significantly ramp its capacity and become the world’s fourth largest automaker.

| Name |

Industry |

Reasons for state ownership |

Which part is state-owned? |

Is it going to be sold? |

| China National Petroleum Corporation (China) | Oil and gas production, oil refining process | Strategically important enterprise | 100%, owns PetroChina (directly owns 86,35%), which now owns most of the company’s assets | Since the company’s creation in 1999, the shares of PetroChina have been gradually sold |

| Deutsche Bahn AG (Federal Republic of Germany) | Railway transport | Historically centralised railway infrastructure | 100% | The decision to sell 24,9% of the company was approved in July 2008 but postponed due to the global financial crisis. In 2015, the Monopolies Commission called for privatisation |

| Japan Post Bank (Japan) | Finance | Established in 2006 as part of the unbundling of Japan Post with the purpose of further privatisation | 74,15% belongs to Japan Post Holdings, 80,49% of which belongs to the state | Initial public offering (IPO) took place in October 2015, Japan’s biggest sale of state property since 1987 |

| Korea Electric Power Corporation (Korea) | Electricity generation, transmission, and distribution | Strategically important enterprise | 18,.2% — government, 32,.9% — Korea Development Bank | Shares traded on the stock market since 1989 |

| Proximus Group (Belgium) | Telecommunications | Monopoly (since creation in 1930) | State - 53,51% | Initial public offering (IPO) took place in 2004, and enabled purchase of assets and modernisation |

| LOTOS GROUP SA (Poland) | Oil and gas production, oil refining process

| Strategically important enterprise | State - 53,19% | Initial public offering (IPO) took place in 2005, and enabled purchase of assets and modernisation |

| ČEZ (Chech Republic) | Electricity generation, transmission, and distribution | Strategically important enterprise | State - 69,78% | A part of shares was sold during the 1994 mass privatisation, another 7% were listed on the stock market |

| Telenor (Norway) | Телекоммуникации | Monopoly (founded in 1855 as a provider of telegraph services Telegrafverket) | State - 54% | Partially privatised in 2000 |

Authors: Oleksandr Zholud, Ilona Sologub, Olena Bilan, Veronika Movchan, Oleksandr Talavera, Alex Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Tymofiy Mylovanov