The Ukraine Reform Monitor provides independent, rigorous assessments of the extent and quality of reforms in Ukraine. The Carnegie Endowment has assembled an independent team of Ukraine-based scholars to analyze reforms in four key areas. To kick off a series of regular publications, this first memo offers a baseline assessment of the reform process as it stands a year and a half after the Euromaidan protests and the fall of Viktor Yanukovych’s government

Political and Judicial Reform

- The first step in constitutional reform was taken in February 2014, when the Yanukovych-era system was replaced with a mixed parliamentary-presidential system that limited the powers of the presidency. The next major step, a decentralization package, is currently being reviewed by the parliament.

- Legitimacy of the political order was restored through free and fair presidential (May 2014) and parliamentary (October 2014) elections. Ukrainians chose a new president, and a pro-reform coalition was formed in the Rada, or parliament. This coalition and the alliance between President Petro Poroshenko and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk is currently under strain; many observers believe it may not last much longer and that new elections are possible.

- Ukraine signed and ratified an Association Agreement with the EU in June 2014. The Association Agreement includes a raft of commitments to governance reforms. At Moscow’s behest, implementation of the agreement was postponed until December 31, 2015. Two EU member states are still to ratify the agreement. Moscow persists in its attempts to dilute the Association Agreement and prevent Ukraine from implementing it.

- Ukraine has adopted a package of anticorruption laws and established a set of institutions to fight corruption. The general prosecutor’s office has been the agency most active in this agenda. Judicial processes have been improved to introduce greater transparency and opportunities for public oversight of corruption cases. There have been no high-profile convictions yet.

- A new law on the prosecutor’s office was approved in autumn 2014. It was amended in July 2015 to make prosecutors more active in anticorruption activities. Local prosecutors’ offices are being reformed. All local-level prosecutors and their deputies are being dismissed, and they will be replaced by some 700 new regional prosecutors, who will be appointed by the general prosecutor’s office in Kyiv.

- The National Anti-Corruption Bureau and the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption have been established. The bureau’s head was elected by a board of representatives from all branches of government in an open competition. The bureau, an independent body fighting corruption at the highest ranks of officials, is expected to be fully functional by September 2015. The agency, a central government executive authority with a special status, started work in April 2015.

- A lustration process was launched in the civil service and in the judiciary in 2014. The adopted legislation on lustration has been selectively applied and was criticized by the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission. The law is under review in the Constitutional Court of Ukraine.

- Judicial reform has been slower than reforms in other areas. A comprehensive set of draft laws on judicial reform is awaiting approval in the parliament. These draft laws introduce changes regarding the selection, promotion, and prerogatives of judges; strengthening the independence of the judiciary; and providing citizens with faster and fairer access to the justice system.

Economic Policy

- The Poroshenko-Yatsenyuk government has embraced a robust economic reform agenda. Key documents outlining these reforms are both international (the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement and Association Agenda, the IMF-Ukraine Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies) and domestic (the Coalition Agreement, the Program of the Cabinet of Ministers, and Strategy 2020). The Coalition Agreement is the key document that lays out the reforms to be implemented.

Fiscal Policy

- In 2014, notable changes to the Tax and Budget Codes were made, which reduced the number of taxes and allowed for additional revenues for local budgets as part of the decentralization process.

Banking and the Financial Sector

- The central bank is seeking to clean up the banking system: more than 50 banks have been declared insolvent since the end of 2013, and information on the ownership structure of banks has been made more transparent.

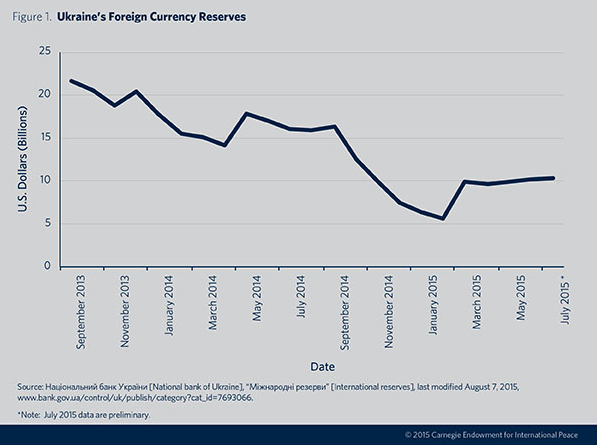

- Trust in the banking system remains low. Foreign currency reserves continue to shrink; as of mid-2015, they are at $10.4 billion—roughly half of December 2013 levels (see figure 1).

The Exchange Rate

- After fifteen years of artificially pegging the hryvnia to the dollar, the central bank introduced a floating rate regime and liberalized the foreign exchange market. This resulted in a 50 percent devaluation of the hryvnia in early 2015. To prevent capital flight and further currency devaluation, the government was forced to introduce capital controls in late February.

- The unofficial exchange rate was more than 20 percent above the official one at the beginning of the year; by mid-2015, it was almost equal to the official exchange rate.

Inflation Targeting

- In December 2014, the Monetary Policy Committee was created within the National Bank of Ukraine to formulate monetary policy.

- In June 2015, two laws boosting the operational independence of the central bank were approved by the parliament.

The Energy Sector

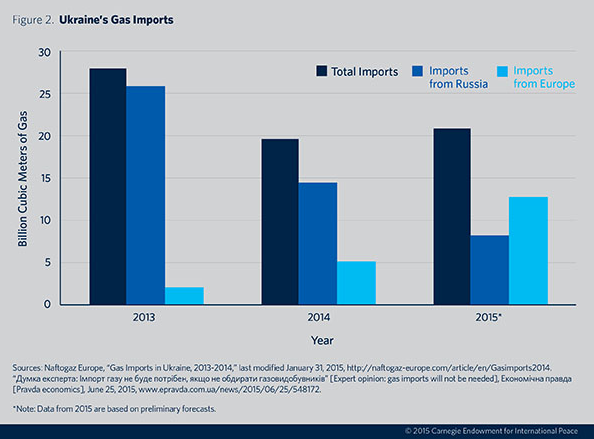

- In 2015, as much as 60 percent of Ukrainian gas imports will come from Europe (including reimports of Russian gas). The remaining 40 percent will come directly from Russia. In 2013, the latter figure was over 90 percent (see figure 2). This reversal of gas trade is a major accomplishment for Ukraine in its quest to loosen its dependence on direct imports of Russian gas.

- A three- to fivefold hike in household gas tariffs went into effect in April 2015. To support households, subsidies were introduced. These are not given directly to households to choose how to use them but to Ukraine’s national oil company, Naftogaz, thus decreasing incentives to save gas.

- A law on the natural gas market was adopted, creating necessary conditions to harmonize Ukraine’s legislation with the third EU energy package and ensuring nondiscriminatory access for independent gas suppliers to the gas transportation system.

Deregulation and Improvement of the Business Climate

- The parliament adopted a law on investor protection and abolished a number of regulations.

- The parliament also abolished a number of state agencies with reputations for bureaucratic incompetence, inertia, and corruption. Examples include the transfer of drugs and vaccine procurement to the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the closing down of the state agency Ukrekoresursy, responsible for recycling.

Public Governance

- A requirement to provide open data on the budget was introduced in April 2015 (and will enter into force in September 2015).

- Several ministries have published information on state procurement.

- The Ministry of Economic Development and Trade is getting ready for a far-reaching series of privatizations. The ministry has published a report with the financial statements of the top 100 state-owned enterprises.

EU Norms

- Ukraine must adopt 426 EU norms by 2025. So far it has adopted two completely and nine partly.

IMF Requirements

- Ukraine has been implementing the major requirements of its $17.5 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) Extended Fund Facility program. It managed to make an interest payment to creditors at the end of July 2015. This staved off a default and led to the release of a second IMF disbursement worth $1.7 billion (a first $5 billion tranche was disbursed in March). This second disbursement comes with a new set of structural reform benchmarks.

National Security

Security Challenges

- A new national security strategy was approved in May 2015, prioritizing territorial integrity and a defense upgrade in response to key security threats, including Russian aggression and an inefficient national security system. Corruption and the ongoing economic crisis were identified as key security challenges in the strategy.

- A draft law has been introduced in the parliament calling for a full economic blockade of portions of Luhansk and Donetsk, which are not controlled by the Ukrainian government. Several roads into these occupied territories have been closed, and new rules for passing through checkpoints on the borders have been announced by the Security Service of Ukraine. In accordance with the new procedures, the transportation of goods into the occupied territories is prohibited, with the exception of humanitarian aid and goods transported by railroad.

- The Minsk II accord is considered a failure in Kyiv because of the lack of proper monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, the continued Russian military buildup along the border between Ukrainian and occupied territory, and ongoing (though limited) casualties from sporadic fighting between Ukrainian forces and pro-Moscow separatists.

- The armed confrontation in the town of Mukachevo in July 2015 between a private security group working for a Rada deputy and members of the nationalist Right Sector political party cast a spotlight on significant internal security problems in Ukraine. The problems stem from a combination of organized crime, corrupt law enforcement agencies, illegal trafficking of goods and weapons, proliferation of weapons in the country, and an increasing militarization of some political groups.

Defense

- NATO and Ukraine have signed a memorandum of agreement that will facilitate the implementation of the NATO-Ukraine C4 Trust Fund established to help Ukraine reform its armed forces. The C4 fund will improve Ukraine’s command, communication, control, and computer capabilities, interoperability with NATO, and ability to participate in NATO-led exercises and operations.

- In the 2015 budget, military spending was increased to 2 percent of GDP, the standard NATO target.

- Two NATO standards on the quality of body armor and uniforms have been adopted to modernize the army’s notoriously corrupt logistics and supply system. The Ministry of Defense started testing an electronic procurement system aimed at tackling corruption and improving the effectiveness of budgetary spending.

- The U.S. government has provided $75 million in nonlethal military assistance out of the $200 million allocation announced earlier in 2015.

Ministry of Internal Affairs

- A new law on the national police has been adopted together with a package of laws improving the collection of traffic fines and reorganizing traffic police registration centers, known to be highly corrupt.

- The ministry launched a new traffic police service in Kyiv in July 2015 and is getting ready to do the same in Lviv, Kharkiv, Odessa, Dnipropetrovsk, Mykolaiv, Uzhhorod, and Lutsk over the course of the next four months. New selection procedures and training standards as well as standard operational procedures were developed for the new patrol service.

- The U.S. government provided $15 million for the traffic police project. The Canadian government announced a package worth U.S. $4 million in support of the reform, and the Japanese government supplied new vehicles.

Security Service of Ukraine

- The dismissal of the chief of the Security Service of Ukraine and his deputies in mid-June amid allegations of corruption and contraband smuggling by members of various law enforcement agencies showed that the work of the security services remains highly corrupt.

National Guard and Volunteer Battalions

- With a 2015 increase in funding, the Ukrainian National Guard has been building up its capabilities—including increasing the number of units, modernizing weaponry, and upgrading training programs in line with U.S. training standards and with assistance from American trainers.

- The volunteer battalion Tornado, reporting to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, was disbanded amid allegations of involvement in smuggling and violent crimes.

Decentralization

- A decentralization reform package was introduced in December 2014 through major amendments to Ukraine’s Budget Code developed by the Ministry of Finance. The reform removed a series of budgetary bottlenecks, which previously obstructed the effective delivery of services and economic development at the local level. It introduced two additional types of local taxes (a destination-based local excise and a property tax), thereby creating revenue sources for local self-government.

- The fiscal decentralization reform introduced transfer financing for all decentralized functions except health, secondary education, and vocational education. The new system aims to partly equalize per capita revenue, rather than expenditure needs.

- The reform significantly expanded opportunities for local borrowing. The new budgeting law allowed external loans (including private ones) for all cities. External borrowing is allowed, provided that the Ministry of Finance does not submit objections within a month, debt servicing does not exceed 10 percent of the budget, and total debt does not exceed a legally enshrined ceiling.

- The new budgeting law committed to treat small communities in the same way as bigger municipalities if they voluntarily amalgamate, providing a strong financial incentive to administrative consolidation. A number of regions started to design regional plans for the amalgamation of communities.

- Prior to the decentralization reform, procedures for financing local investment projects were opaque. Financial grants for capital investments were channeled to local budgets via targeted subventions without clear or transparent criteria. The fiscal decentralization reform introduced a new system for regional development: the central government has committed to earmark 1 percent of its entire revenue for local investment, based on a new, transparent, competition-based approach and with 10 percent co-funding.

- In July 2015, draft changes to the constitution regarding decentralization were introduced in the parliament. The parliament voted to send these draft changes to the Constitutional Court to verify compliance with two existing constitutional provisions: article 157 (on human and civil rights) and article 158 (on the procedure of amendments submission). Approved by the court, the changes now need to pass through first and second readings in the parliament; the first requires a simple majority of 226 votes, the second a constitutional majority of 300 votes. If the process goes as planned, in spring 2016, Ukraine will have a significantly amended constitution. The status of the separatist-held territories in the east of the country remains unresolved and is the subject of intense debates in the Rada.

Overall Assessment

- Political reforms have succeeded in rebuilding the political system after it collapsed in February 2014 but have not yet produced a well-functioning democracy. The executive branch is split between the president’s and the prime minister’s offices, and this has undercut the reform momentum. Legislative oversight of the government remains weak, and the parliamentary opposition provides no effective check. The pace of judicial reform continues to be slow, and political control of the judiciary is still a problem.

- Ukraine has so far avoided default and worked aggressively to stabilize the economy in the face of unprecedented challenges and pressures; support achieved at least temporary macroeconomic stability, but not without pressure from the international community and civil society remains crucially important to staying the course. OAt this juncture, only a few regulatory changes can be considered truly systemic reforms. In many cases, adopted laws are useful, but constitute rather largely cosmetic changes. Nevertheless, there are clear, positive trends in a number of areas, though—e.g.for example, deregulation, opening up data, reforming the energy sector, cleaning up the banking sector, and implementing anticorruption measures.

- Given the scale of the security crisis in the east, law enforcement agencies have responded to security threats relatively well in an extremely difficult environment. The army, national guard, and police are gradually becoming better equipped and more capable of responding to the challenges of the conflict with Russian-backed separatists. The security service is responding well to the need to neutralize the threats of terrorist attacks in the areas bordering the antiterrorism operation zone. However, allegations of corruption, trafficking of illegal goods and weapons, and poor management in various law enforcement units are so widespread that they overshadow successes on the reform front. Progress on security and law enforcement reform is mixed and uneven, and mistrust in law enforcement agencies remains a problem.

- Decentralization reform has the potential to install a well-balanced, significantly decentralized public financial management system. However, it also entails risks. It may substantially increase the level of local debt and corruption, and create fiscal vulnerabilities. The introduction of a local property tax is a progressive measure, but many communities need technical support in developing local systems for administering this tax. The major source of local revenue—the personal income tax—remains based on employment rather than residence. This distorts allocation toward more affluent communities and undermines plans to introduce local income tax surcharges. The politics of decentralization plans are likely to be highly complicated.

on Carnegie Endowment For International Peace

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations