The 2008 financial crisis brought to the common language a new abbreviation – QE (quantitative easing). A non-conventional instrument that may cause high inflation, QE became a mainstream tool in 2009 when the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and other banks in advanced economies used it on an enormous scale to soften the consequences of the financial crisis.

Today, as the COVID-19 crisis unfolds, some governments of emerging-market countries are starting to use QE to stimulate their economies. There are voices in Ukraine calling for adopting this instrument to fight the current crisis.

What is QE?

As a rule, central banks provide more money to the economy (lower interest rates) in times of economic crisis or recession to boost output, and decrease money supply (raise interest rates) during economic booms to control inflation (see Box).

However, when central banks run out of ‘conventional ammunition’ of changing the interest rate (i.e., when the interest rate becomes zero or negative), they may try unconventional policies to increase money supply, such as direct purchases of government bonds and/or corporate bonds or providing ‘unlimited’ liquidity to banks that in their turn lend money to firms and households. This ‘direct’ provision of money to the economy is called quantitative easing (QE). Clearly, QE means printing money (although of course this money is in the electronic form and not literally printed).

Who and when used QE?

The first large-scale attempt of QE was implemented by the Bank of Japan in the early 2000s. This policy was aimed to reverse a decade-long low-growth and deflationary trend triggered by the burst of the real-estate bubble in the late 1980s. For a variety of reasons, this policy did not restart economic growth. The second QE attempt in Japan was in 2010. The amount of liquidity provided to banks was nearly 60% of GDP. Since then, inflation was negative only in two years, although only once it exceeded 1%.

The most famous cases of QE however were massive asset purchases by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) in response to the 2008 financial crisis. Between 2008 and 2014 the Fed’s balance sheet increased from below 5% to about a quarter of GDP (since then it tightened a bit with the ‘normalization’ policy). Fed purchased ‘toxic’ assets as well as ‘long’ securities to provide liquidity to market players and lower market uncertainty. In other words, in addition to being a lender of last resort it became the ‘purchaser of last resort’.

In a similar fashion the ECB balance sheet more than doubled between 2008 and 2019 – from EUR 2 trillion to EUR 4.5 trillion, mostly via purchases of euro-denominated securities.

Nevertheless, such massive injections of money into the US and European economies did not lead to inflation (which would be predicted by the economic theory). Why? The short answer is that neither households nor firms were eager to spend and banks were conservative in lending. As a result, inflationary pressures were weak. In addition, US dollar and Euro are the world reserve currencies.

Ukraine also had a QE experience, although very unfortunate. In 1992-1994, the National Bank of Ukraine provided direct credit to the government as well as to firms. This resulted in hyperinflation in 1993 (over 10000%) and double-digit inflation until 2000.

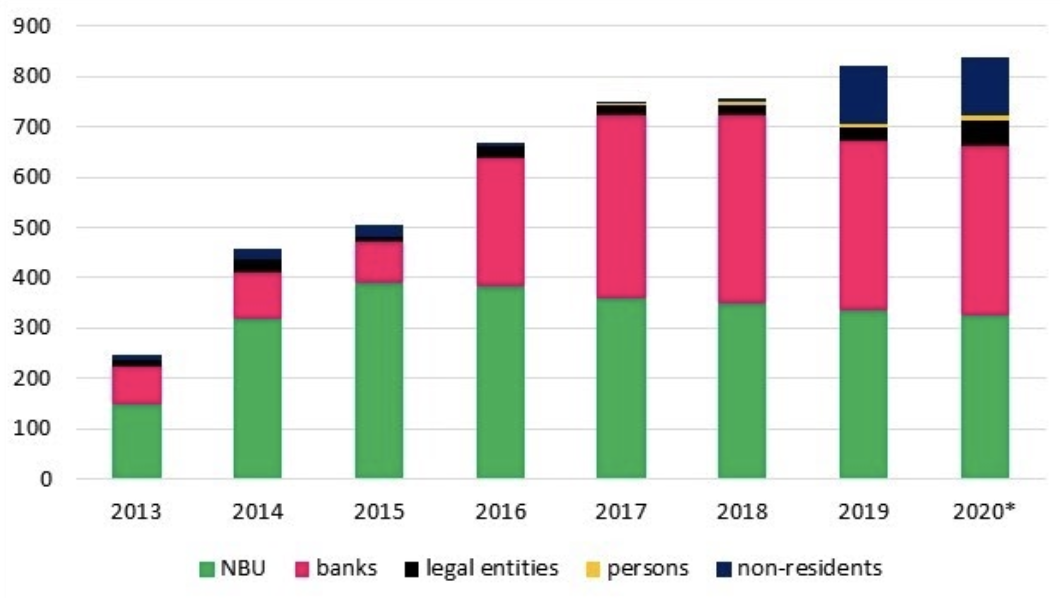

The second episode of QE was in 2014-2015, when the government issued bonds to increase capital in state-owned banks and subsidize heavily loss-making state-owned gas company Naftogaz. These bonds were partially purchased by the NBU. In two years, NBU’s portfolio of government bonds increased by 2.6 times (figure 1). This increase was equivalent to 14% of GDP. In 2014 inflation was 25%, in 2015 – 43%, and it lowered to single digits only in 2018 (other factors, primarily the natural gas price hike, also contributed to high inflation during this period). Both episodes of QE were characterized not only by high inflation but also by a massive depreciation of the national currency and increase in dollarization (which is still high even today).

Figure 1. Ukraine’s government bonds by holder type, billion UAH

Source: NBU. The data is provided as of end-year, for 2020 – as of April 7th.

So why cannot Ukraine copy the US or EU experience? There are two main factors. The first factor is the real sector. In 1992 production in Ukraine fell dramatically when supply chains between former Soviet Union republics collapsed. In 2014, Ukraine lost 25% of its industrial capacities. Thus, both periods were characterized by supply shocks (although in the early 1990s the demand shock was also huge). And when the supply contracts, prices must rise unless the demand falls even more. The second factor is that Ukraine does not issue a world reserve currency. In times of economic crises investors run from currencies like the hryvnia to ‘safe havens’ such as USD, EUR, Swiss franc. Thus, US and EU can borrow cheaply from the rest of the world. In contrast, countries like Ukraine cannot. A run on the national currency causes its depreciation which adds to price growth.

Today’s shock is both supply and demand. Supply contracts because many people must stay at home and cannot work. Demand falls because many people not only lose a physical ability to spend (shops are closed) but also lose their income and start spending less. In contrast, the Great Recession was largely a fall in demand with little change in supply. Furthermore, in 2008-2009 it was not clear who is holding the toxic assets and will become insolvent tomorrow. Today, it is pretty clear which industries and people will suffer the most. It is also clear that when the pandemics is contained, economies will rather quickly return to growth. The remaining unknown is when the pandemic will actually be taken under control (estimates range from summer-2020 to mid-2021).

Meanwhile, the governments around the world are taking extraordinary measures to support their economies. US Fed cut the interest rate from 1.25 to 0.25, ECB rate was already negative at -0.5% in 2019. To complement monetary policy, countries provide large fiscal packages that include both indirect measures such as tax breaks or deferred payments on loans and direct payments to businesses and people. The USA as well as EU countries are going to pay for these measures with the help of QE, i.e. printing money.

This time some emerging market countries follow the case. For example, the Bank of Poland is allowed to buy government bonds from commercial banks in addition to other monetary measures such as lower reserve requirements and refinancing of new loans issued by commercial banks to businesses and households. The Central Bank of Turkey announced that it will purchase government bonds on both primary and secondary markets, and accept asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities as a collateral. It also announced higher limits for loans to exporters and service companies (an equivalent of $9 billion was allocated to this purpose so far). Whether these policies are successful remains to be seen. Poland has almost 20 years of below 5% inflation thus it may expect an only moderate increase in prices. On the other hand, Turkey already had a currency crisis when it played with the central bank’s independence. It may well face another one caused by QE.

Can Ukraine follow their case? First, in Ukraine the key rate is 10%. So the National Bank has not run out of conventional ‘weapon’ to fight economic crisis – it still can lower the interest rate to stimulate the economy.

Second, slightly over 10% of internal government bonds are held by non-residents. If the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) starts purchasing government bonds on the secondary market (and it cannot do this on the primary market), non-residents will be the first to exit. Naturally, they will be willing to exchange their hryvnias for foreign currencies which will cause downward pressure on the hryvnia. The depreciation of the hryvnia may cause an indirect effect when people would be willing to convert their deposits into dollars. This may cause a full-scale run on the hryvnia.

Third, it is not clear that borrowing money from the NBU is the best deal for the government. The government should pay the NBU the market rate, which is above 10%. In contrast, the IMF provides loans at about 2%.

Finally, if the central bank responds to the government’s request to print money, it will lose trust of households and firms in Ukraine and thus will not be able to control inflation expectations. But if inflation expectations increase, actual inflation will increase too. Given Ukraine’s history of high and volatile inflation, this may lead to a hyperinflation again.

As we previously argued, the policy response has to be big and targeted towards the poorest, local governments, and infrastructure projects. Besides already provided indirect measures (tax breaks, loan relief, simplifying getting unemployment benefits), the government needs to spend money on purchases of hospital supplies (preferably from domestic producers) and other goods and services needed to contain the virus. But it should do so with the money it borrowed from the IMF, World Bank and other international financial institutions rather than from the central bank.

One of the most important lessons of economics is that there is no free lunch. And there is no free (‘just printed’) money either. For what seems to be cheap and obvious way to fix the economy will actually worsen not only the current crisis but also the state of the economy in the long run.

How central banks create money?

In a classic economic theory, a central bank can change the amount of money in circulation by open market operations, i.e. trading of government bonds with other market players (in many countries, including Ukraine, the central bank cannot purchase bonds directly from the government). When a central bank purchases government bonds, the amount of money in circulation increases. This lowers interest rate and thus stimulates the economy — at lower interest rates firms can borrow and invest more, while households can borrow and consume more. When a central bank sells government bonds, it reduces the amount of money in circulation and raises interest rate. This makes economic agents less likely to spend and more likely to save. In its turn, lower spending reduces price growth (inflation).

However, in practice the majority of central banks directly announce their policy rates taking into account inflation target and economic growth. This announcement implies that a central bank is ready to provide commercial banks with money at the specified rate (it often accepts government bonds as a collateral). Such loans to commercial banks increase the amount of money in the economy. When the interest rate is lower, banks can borrow more and issue credit to their clients.

Other ways to inject money into the economy are:

- lowering the reserve requirement ratio, i.e. the share of deposits banks have to keep as reserves. This ratio defines how much money banks can issue as loans. It also defines the money multiplier which in theory is equal to the inverse reserve requirement ratio. This means that if the requirement ratio is 10% then UAH 1 provided by the NBU to a commercial bank creates UAH 10 of new loans. In practice the multipliers are lower because banks keep more reserves in order to accomodate asset risk;

- providing refinancing to commercial banks that issue loans to firms. When doing this, central banks usually extend the list of assets which they would accept as a collateral (e.g. these can be corporate bonds).

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations