In August, the Turkish economy became one of the most discussed in the world, but there’s nothing to be glad about. The main news headlines were caused by sudden weakening of the Turkish lira (up 40% since the beginning of the year, the weakening reached a maximum of 45%, from 3.78 liras / USD by the end of 2017 to 6.89 lire / dollar, as of August 13) and due to the reasons of this situation.The Turkish currency crisis is the direct result of populist economic policies which have led to the accumulation of macroeconomic imbalances, while the U.S. sanctions on Turkey officials and on steel exports served as a trigger. VoxUkraine editors analyzed the causes of the Turkish crisis and offered lessons to be learned in Ukraine.

The Turkish administration has fallen into the same trap as many others who think that economic laws do not apply to their countries until an economic crisis hits them. For example, the IMF in its April 2018 piece on Turkey warned that the economy was overheated and could run aground in the nearest future. A somewhat similar situation was observed in Ukraine in 2005-2007 when it led to a severe economic contraction and currency devaluation as the global crisis hit in 2008-2009.

In this editorial article we first review the macroeconomic imbalances that contributed to the current crisis and policies that exacerbated it, then account for possible future scenarios and draw lessons for Ukraine.

Why do we care about Turkey?

Turkey is a relatively large economy, with GDP at PPP equal to USD 2.173 tln in 2017 (13th largest in the world). Politically, the country is viewed as both a buffer and a wall against islamic militarism and massive migration from the war-ravaged Syria to Europe. The number of Syrian refugees in Turkey is estimated at 3.6 mln people, while the EU took in about 1 mln and even this relatively small number has caused a lot of discontent in many member states. The economic downturn in Turkey may affect European financial markets that are interlinked with the country and cause a new wave of refugee migration to the EU.

What has led to currency crisis?

Over the past two decades, Turkey has been one of the fastest growing economies as well as one of the most attractive destinations for foreign investors. Economic growth averaged 5.8% y-o-y over 2002-2017, inflation was tamed to single-digits and capital investment to GDP ratio rose from 18.1% in 2001 to 28.4% in 2015, partially due to the inflow of FDI and foreign debt. This stellar economic performance was a result of several important economic reforms introduced after 2001 banking crisis, positive demography (Turkey population increased from 64.2m in 2001 to 78.3m in 2015) and more recently low global interest rate environment. See the Appendix for the detailed economic history of the pre-crisis Turkey.

Over the past two decades, Turkey has been one of the fastest growing economies as well as one of the most attractive destinations for foreign investors. Economic growth averaged 5.8% y-o-y over 2002-2017, inflation was tamed to single-digits and capital investment to GDP ratio rose from 18.1% in 2001 to 28.4% in 2015, partially due to the inflow of FDI and foreign debt.

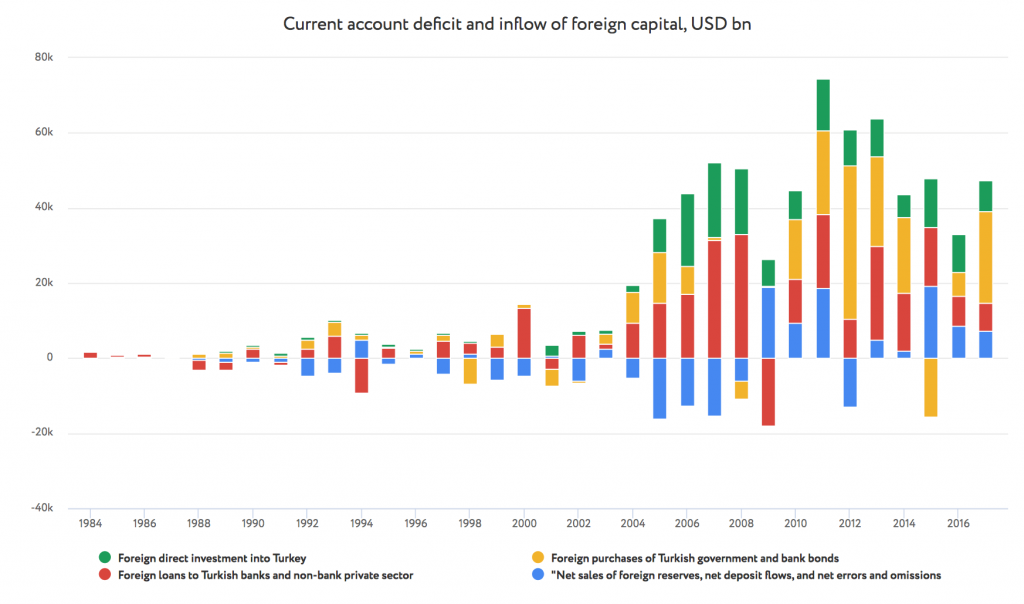

Turkey is crucially dependent on foreign capital inflows (Figure 1). Its current account deficit is higher than 5% of GDP and it needs to repay USD 179 bn in external debt over the 12 months (as of June 2018), 57% of which is owned by banks. For comparisons, exports of goods and services in the first 6 months of 2018 amounted to USD 105.8 bn and the current account deficit for the same period was USD 31.2 bn. In the previous years the debt was mostly rolled over, but now, with foreign investors being uncertain, it creates a huge downward pressure on the lira.

Foreign investors started to leave Turkey earlier this year: the net flow of portfolio investments turned negative in February and an outflow from the private external debt started in May. In the first half of 2018, the net annual portfolio investment inflow totalled USD 6 bn, compared to USD 17.8 bn over the same period of 2017. Moreover, since March 2018 the net inflow has been negative, with investors getting out of Turkish debt and (to a lesser extent) equities. As a result, the lira has lost 57% of its value between March 31st and August 14th, when it peaked at about 7 lira per USD. The stability of the heavily dollarized banking sector is now likely to deteriorate since about 40% of loans and 60% of deposits are in US dollars.

Figure 1. Current account deficit and inflow of foreign capital, USD bn

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Insufficient countermeasures and populist politics

Turkey’s central bank has not been completely idle. Since the start of 2018, when inflation accelerated and the lira weakened, it increased its key policy rate (the one week repo auction rate) from 8% to 17.75%. While the hike looks significant, most observes suggest it was too little and too late: it was expected that after the elections (held on June 24th, 2018) the central bank would not be constrained by political considerations. However, it kept the key rate unchanged, despite inflation constantly accelerating from March 2018. Only in September the policy rate was raised to 24%.

While raising interest rates to curb inflation is a standard tool used by central banks, in the short-run it is not enough, especially if other inflation drivers remain in place. For today’s Turkey, tight fiscal policy may be more important than tight monetary policy. However, an expansionary fiscal policy has been key to Erdogan’s drive to consolidate power after defeating a coup attempt in 2016. In the run-up to the 2018 presidential elections, Erdogan has introduced a number of growth-promoting programs, as well as some generous handouts to the pensioners and the poor. Additionally, the government supported public-private partnerships by guaranteeing their loans, often without adequate control. Tellingly, a large handout was announced on the very same day that the IMF warned Turkey of its overheating economy. Given the forthcoming local elections in 2019, any fiscal tightening is unlikely to happen soon. The increasing grip of Erdogan on power further magnifies the impact of his unorthodox economic views. Erdogan’s son-in-law is now the minister of finance, and the president believes that inflation is caused by ‘external enemies’ rather than his own policies.

While raising interest rates to curb inflation is a standard tool used by central banks, in the short-run it is not enough, especially if other inflation drivers remain in place. For today’s Turkey, tight fiscal policy may be more important than tight monetary policy. However, an expansionary fiscal policy has been key to Erdogan’s drive to consolidate power after defeating a coup attempt in 2016.

The central bank independence, and thus inflation targeting, also seem to be undermined by the Erdogan regime. The 2018 constitutional reform allows the president of Turkey to appoint the members of the monetary policy committee, which sets the strategic goals for the central bank and gives him the right to dismiss the CB governor at any time (previously s/he had a 5-year immunity). Thus, the president can effectively control the monetary policy.

President Erdogan has stated on multiple occasions that higher rates are causing inflation: they are “mother and father of all evil” and should be lowered despite the high inflation. This stands in direct contradiction to the mainstream monetary theory, which states that not only should interest rates go up to stabilize prices but they also need to do that faster than any rise in inflation — the so-called Taylor principle.

Instead of giving a greater concern to existing domestic problems, the rhetorics of the president has turned against the outside world and domestic institutions. For example, Erdogan described the weakening of the lira as “the ‘missiles’ of an economic war waged against Turkey”. Like in many authoritarian regimes, the propaganda in Turkey actively accuses “foreign influence”– from the US State department to George Soros to Israel — of all problems within the country. Another ‘enemy of the state’ is the civil society – president has accused ‘economic terrorists on social media’ of the lira’s weakening.

One of the populist claims is that the US ‘weaponized’ its currency to harm other markets. As with many conspiracy theories there is a shadow of truth in it, namely that an increase in the US interest rates presses emerging markets to up their rates as well or face an outflow of foreign capital. However, its purpose is not to intentionally hurt any state but to prevent the acceleration of inflation in the US after the decade of quantitative easing that started during the global financial crisis.

The correct answer to the US rate hikes along with an increase in local rates would be an improvement of the investment climate to drive down the risk premiums.

However, current actions of both the authorities and some ordinary Turks – from Erdogan calls to stop buying US-made consumer electronics to Turkish citizens cutting/burning dollars or bludgeoning iPhones – are doing just the opposite.

What should a country in a similar situation do?

The recipe for Turkey is not different in main points from the recipe for any other country, suffering from external and internal imbalances.

If foreign capital suddenly stops to flow into an economy that relies on it, what follows is a deep economic downturn, elevated inflation, massive currency depreciation, and (partial) default on foreign debt. One may think that Turkey will have rough times as there is no easy solution to its troubles. However, the playbook for how to address the crisis is relatively straightforward and it has been been tested in many countries that have suffered from external and internal imbalances.

If foreign capital suddenly stops to flow into an economy that relies on it, what follows is a deep economic downturn, elevated inflation, massive currency depreciation, and (partial) default on foreign debt. One may think that Turkey will have rough times as there is no easy solution to its troubles. However, the playbook for how to address the crisis is relatively straightforward and it has been been tested in many countries that have suffered from external and internal imbalances.

The first step is to stop the panic, which typically means some form of capital controls and fresh hard-currency funding provided by the IMF and possibly other governments. There were steps made in this direction – an agreement with Qatar and negotiations with France for example. However, the funds these countries have pledged are not enough. Simultaneously, the government should convince foreign creditors to provide a temporary (if not permanent) relief on debt payments. If attempts to obtain debt relief are not successful, default is a common outcome. It is costly in the longer run but provides a breathing space to maneuver in a crisis.

Once the panic is tamed, the government should adjust its fiscal and monetary policies (i) to provide stimulus to the failing economy and (ii) to assure that the government will be more responsible in the future. The first part may be counterintuitive given that the country has got into the crisis because of over-stimulus but this is why the second part is critical. Specifically, as the Greece’s experience showed, the government should not resort to fiscal consolidation (cut spending and raise taxes to reduce fiscal deficit) immediately but rather lay out a credible plan of how it will be more fiscally conservative in the future. Likewise, the central bank can provide large injections of liquidity which may generate more inflation but will also save the financial sector of the economy. Having done that, the central bank should commit to having a responsible anti-inflation policy in the future.

Obviously, other, structural, policies should be adjusted as well. It is critical to convince the public that this plan will be fulfilled once the acute phase of the crisis is over.

What will happen if the Turkish government continues its course of international confrontation? Political constraints may be such that the government cannot accept support from the IMF, the EU and the U.S. or these players find it impossible to offer such support.

Given the scale of the problem, it is unlikely that any power (even France or Qatar) would be able to provide the necessary financing – and so Turkey will hence be on its own. In this scenario, Turkey should brace for a hard landing. The lira will likely have to depreciate even further, some kind of a default is inevitable, recession and inflation will follow. Given limited help from abroad, the government will have to raise interest rates and implement fiscal consolidation to address the imbalances but these policies will deepen the crisis and make it more painful.

Given the scale of the problem, it is unlikely that any power (even France or Qatar) would be able to provide the necessary financing – and so Turkey will hence be on its own. In this scenario, Turkey should brace for a hard landing. The lira will likely have to depreciate even further, some kind of a default is inevitable, recession and inflation will follow.

Perhaps the worst case scenario is when the government continues to ignore economic laws and presses the current course. There are abundant examples of how this will end. Venezuela vividly illustrates the magnitude of an economic catastrophe that the country will have to suffer in this case: hyperinflation, economic collapse, blaming external and internal ‘enemies of the state’, and isolation.

How will it affect Ukraine?

Ukraine has a relatively moderate economic exposure to Turkey. Though Turkey is the third largest destination for Ukraine’s exports after the EU and Russia, it accounted for only 5.8% ($2.5bn) of Ukraine‘s merchandise exports in 2017 (vs. 9% Russia and 41% the EU). Imports from Turkey were even smaller: $1.3bn, or 2.5% of the total imports. The top three largest exported items are ferrous metals, oil seeds and grains.

Turkey is a large consumer of Ukraine’s ferrous metals, accounting for 12% of all exports. Ukraine supplies to Turkey mostly semi-finished steel products, which Turkish manufacturers use as an input to produce long steel, which is consumed domestically and exported. Turkey and Ukraine compete on other markets because Ukraine also exports long steel products. Thus, a potential contraction in Turkish investment spending and construction works caused by the lira devaluation could reduce demand for Ukraine’s semi-finished steel. At the same time, U.S. sanctions on Turkey steel products will force Turkish exporters to expand market share in other countries, such as MENA region, potentially expeling Ukraine’s exporters of long steel products. There might also be a more positive scenario. As Turkey buys less semi-finished products from Ukraine and thus produces less, Ukraine can try to sell more of its long steel on the markets previously occupied by Turkey.

Turkey economic woes may also affect Ukraine indirectly. The currencies of other emerging market countries and even developed economies are weakening against the U.S. dollar. Since the start of the year, most of them depreciated more than the hryvnia. This, along with higher domestic inflation, means that Ukraine is losing external price competitiveness against its major trading partners.

On a positive note, Ukraine’s very limited integration into global financial markets coupled with strict capital controls safeguards it from the negative impact of capital outflows which caused serious troubles in Turkey and other countries.

What can Ukraine learn?

The current situation in Turkey highlights several issues which are important for Ukraine.

First, while economic growth is extremely important, ‘growth at any cost’ is not a sound strategy. Economic growth should be accompanied by prudent policies that would prevent the accumulation of imbalances. Such imbalances (e.g. foreign trade deficit, artificially suppressed prices, etc.) lead to costly crises which “wipe off” previous gains. A full liberalization of capital flows can help the economy grow faster but it can also make it more vulnerable to sudden stops or reversals of capital flows. In a similar spirit, the government can use fiscal policy to stimulate the economy but an expansion driven by loose fiscal policy is not sustainable.

Second, central bank independence is a cornerstone of macroeconomic stability. As soon as a central bank becomes a political instrument and a source of employment for cronies and relatives, the punishment from the global financial markets follows quickly.

Third, listening to advice of economists is important. The IMF and others have warned that the Turkish economy is overheated but the authorities haven’t heeded the warnings. Trying to defy economics laws is a poor strategy. Appealing to unique circumstances is not a solution either. Neither the Ukrainian nor Turkish economy is special.

Finally, this case is a very clear illustration of a purely “hand-made” crisis which always results from populists’ attempts to implement their electoral promises in practice. This can serve as a good warning for Ukrainians in the upcoming elections.

Appendix

Modern economic history of Turkey

Up to 1980 Turkey was a relatively closed economy with anemic growth. After a debt crisis, it received help from the IMF and the EU and initiated several important reforms aimed at an economic liberalization and shifting from import substitution to export promotion. The results were positive, with rapidly growing exports and a narrowing foreign trade deficit. The inflow of foreign capital, both FDI and private debt, increased significantly, which supported economic growth.

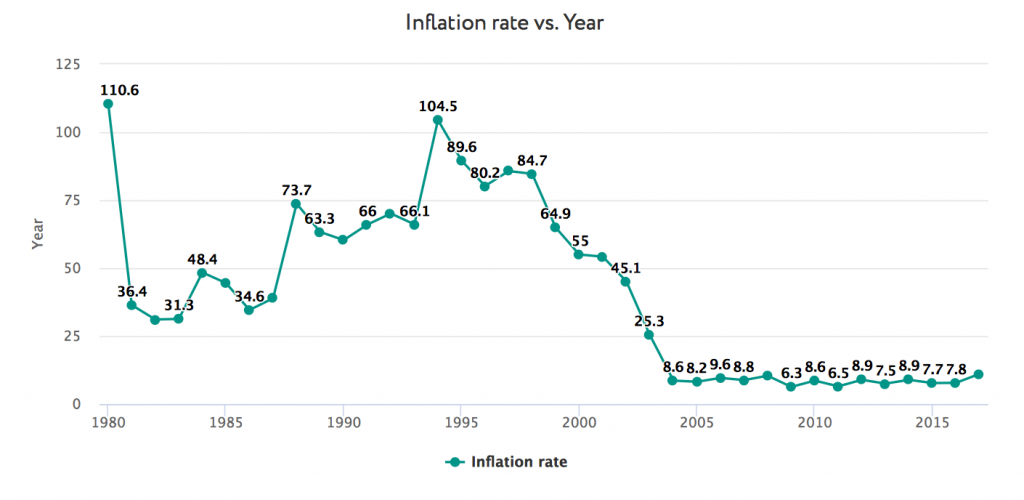

Figure 1. Inflation rate, average consumer prices (annual percent change) 1980-2017, %

Source: IMF

Despite some obvious improvements there were still a lot of problems: inflation remained high averaging 51% in the 1980s and 77% in the 1990s. Average GDP growth improved but was very volatile, with frequent slowdowns and even recessions. The attempts to support an overvalued lira during high inflation led to several episodes of a sharp currency depreciation.

In order to combat this high volatility, a comprehensive monetary reform was implemented, including the introduction of inflation targeting in 2002 and the increase of the central bank independence, along with a more conservative fiscal policy.

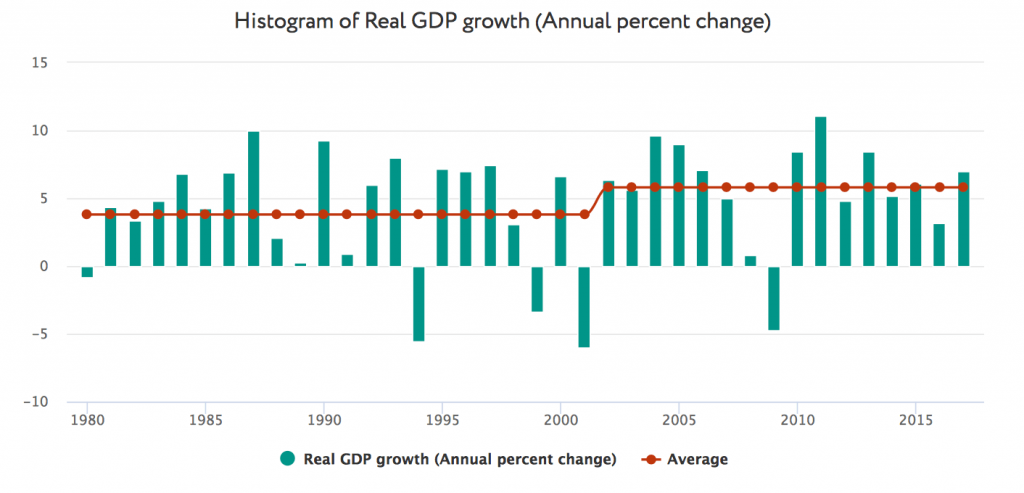

The reform was largely successful: inflation dropped from 37.6% in 2000-2004 to just 8.5% in 2005-2017 (figure 1). As a culmination of the reform, money redenomination was performed in 2005, dropping 6 zeroes from the Turkish lira. This along with relatively stable currency notably improved long-term expectations, supporting investment and economic growth (Figure 2) and contributing to the financial system development.

Figure 2. Real GDP growth, % y/y 1980-2017 (line – average growth before and after inflation targeting was introduced)

Source: IMF

While Turkish authorities were successful in stabilizing the economy and promoting growth, their experience with inflation targeting regime was not particularly appealing. Though slowing notably in early 2000s, inflation persistently outperformed the target, which was set at 5% plus/minus 2 percentage points since 2012 (figure 3) and the spread between the target and actual inflation increased over time. In 2017 actual inflation reached 11.9% because of a soft fiscal policy, significant inflow of foreign capital and a low policy rate (8% in 2017).

Figure 3.

Source: IMF

It was not only actual inflation that moved further from the target. Inflation expectations started to worsen as well (Figure 4), especially since the start of 2018. There were multiple causes: a higher actual inflation in 2017 and Erdogan promises to limit the central bank independence, as well as his rhetorics about the evil of high interest rates.

Figure 4. inflation expectations for next 12, 24 months and next 5 years

Source: The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

Authors

- Rostyslav Averchuk, graduate of the Bachelor program “Philosophy, Politics, Economics” (University of Oxford)

- Oleksandra Betliy, IER

- Olena Bilan, Dragon Capital

- Volodymyr Bilotkach, Newcastle U

- Tymofiy Brik, KSE

- Tom Coupé, Canterbury U

- Yuriy Gorodnichenko, UC Berkeley

- Veronika Movchan, IER

- Alex Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, Lehigh University

- Oleg Nivievskyi, IER

- Denys Nizalov, KSE

- Olena Nizalova, University of Kent

- Nataliia Shapoval, KSE

- Ilona Sologoub, KSE

- Oleksandr Talavera, Swansea University

- Dmytro Yablonovskyy, Centre for Economic Strategy

- Oleksandr Zholud, NBU