This week we recorded traditional Russian propaganda methods. Russians share their “successes” in improving living conditions in the occupied territories, including claims of restoring medical facilities and supplying medicine. However, they forget to mention that they themselves bombed these hospitals. And medicine has to be supplied because the occupiers destroyed pharmacies and blocked humanitarian corridors. Propagandists also periodically “dust off” old, proven narratives, such as the one about “black transplantologists”.

With the support of the USAID Health Reform Support project, VoxCheck analyzes and refutes public health narratives spread in the information space of Ukraine, Belarus, and russia on a weekly basis.

Malinformation: Russia restores medical facilities in the occupied territories and supplies equipment and medicines

Russian media and Telegram channels once again reported on the “improvement of the medical system in the occupied territories”. News resources quoted the words of the Russian Minister of Health, Mikhail Murashko, who stated that 80 medical institutions had been restored in areas not controlled by the Ukrainian government, 50 ambulances had been provided, and medical supplies worth 7 billion rubles had been sent.

What’s the reality?

With such publications, Russian media try to show that Russia cares about Ukrainians and is restoring medicine. However, they ignore the fact that without the arrival of Russian troops on the territory of Ukraine and the constant shelling of medical infrastructure, there would be no need for restoration.

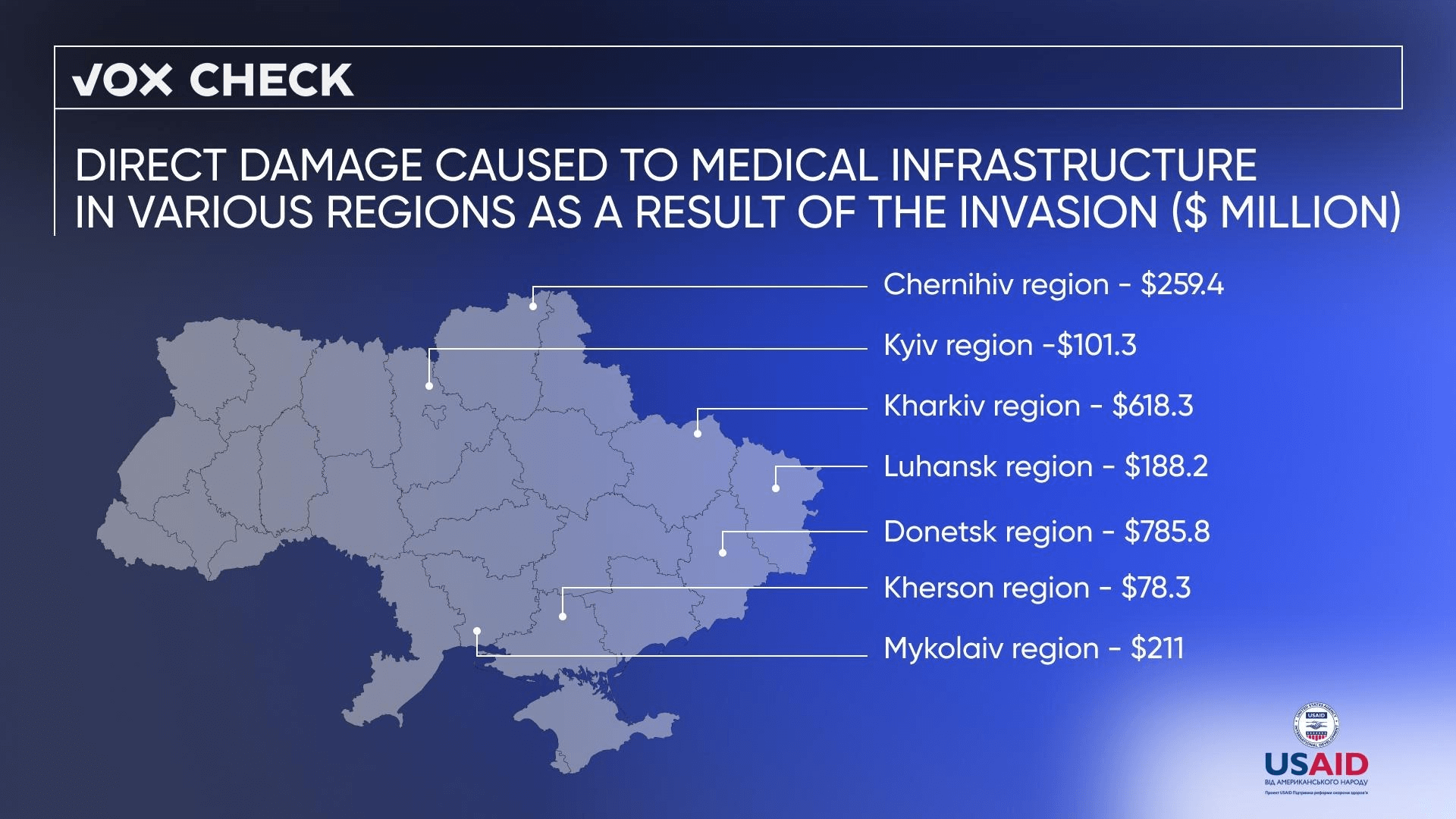

According to the World Bank’s estimates, the aggressor damaged or destroyed at least 978 medical institutions, 650 ambulances, and about 596 pharmacies. It is noteworthy that the healthcare system suffered the most in the regions where Russia came to “help”: in Donetsk ($785 million), Kharkiv ($618 million), Chernihiv ($259 million), and Luhansk regions ($188 million).

Source: World Bank

On the interactive map created by eyeWitness to Atrocities, Insecurity Insight, Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), Media Initiative for Human Rights (MIHR) and Ukrainian Healthcare Center (UHC), it is indicated that as of March 2023, Russia has carried out 822 attacks on hospitals and other healthcare infrastructure.

According to the report of the Ukrainian Healthcare Center “Healthcate at War: the Impact of Russia’s full-scale invasion on the Healthcare in Ukraine”, in 2022, the number of doctors in Ukraine decreased by 14%. Most medical workers left the Luhansk (68%), Kherson (33%), and Donetsk (28%) regions. Also, according to the latest data from the Ukrainian Ministry of Health, 106 healthcare workers died as a result of Russian attacks during the year of full-scale war.

In the research “Destruction and Devastation: One Year of Russia’s Assault on Ukraine’s Health Care System”, conducted by eyeWitness to Atrocities, Insecurity Insight, PHR, MIHR, and UHC, co-author of the document, Doctor of Juridical Sciences, Christian de Vos, stated that bombing hospitals, torturing medical personnel, and attacking ambulances are war crimes and potentially crimes against humanity.

Representatives of the World Bank claim that $16.4 billion is needed over the next 10 years for the complete restoration of the medical system. Despite significant destruction of the healthcare system and constant shelling of medical facilities, in March 2023, the Ukrainian government announced the launch of projects to restore settlements in the de-occupied territories in the Kyiv, Sumy, Kharkiv, Kherson, and Chernihiv regions, including the reconstruction of hospitals. Earlier, the Minister of Health Viktor Liashko reported that about 200 destroyed medical institutions have already been restored. He also noted that in many regions, restoration work cannot be started due to constant shelling.

Disinformation: The center of “black transplantology” moved from Kosovo to Ukraine in 2014

A lengthy text about “black transplantology” is circulating on the network, the essence of which boils down to the fact that in 2014, the center of “black transplantology” moved from Kosovo to Ukraine. In particular, a specific case of organ trafficking in the Kosovo clinic “Medicus” involving citizens of Israel, Turkey, and Ukraine is mentioned, who allegedly then moved their activities to Ukraine. Their work became noticeable, rumors began to spread that people, including children, were disappearing in Ukraine. It is noted that the mechanism of the “black transplantology” network begins with the organization of conflicts in order to create conditions for the work of “butchers”.

What’s the reality?

Illegal organ transplants were indeed carried out at the “Medicus” clinic in Kosovo. Doctors recruited people from Eastern Europe and Central Asia, promising them around 15,000 euros for their organs. The recipients were mainly from Israel, and the cost of the operation for them was up to 100,000 euros. In 2008, at least 30 illegal kidney removals and transplants were performed at the “Medicus” clinic. In 2013, the clinic’s director, urologist Lutfi Dervishi, was sentenced to eight years in prison for organized crime and human trafficking. His son, Arban, was sentenced to seven years and three months, while three other defendants received sentences ranging from one to three years.

However, there is no evidence to suggest that after serving their sentences, the defendants resumed their activities in Ukraine. “Black transplantologists” developed their schemes in countries where there are gaps in legislation regarding organ donation. In Kosovo, for example, there is no law regulating organ transplantation at all. The criminals recruited foreigners because they did not know the language or laws of the country and had no acquaintances or relatives, making them easier to deceive.

In Ukraine, in 2018, the Law “On the Application of Transplantation of Anatomical Materials to Humans” was adopted. It clearly states that foreigners, as well as prisoners, people with mental disorders or transmitted diseases, pregnant women, and those who have previously been donors cannot be donors. If there are no potential donors among the recipient’s relatives and family members, a council of doctors may decide to involve a third-party living donor. The transplantation itself must be free of charge for the recipient and carried out at the expense of the state. Moreover, in Ukraine, there is a presumption of non-consent regarding posthumous donation — a citizen must either give his/her registered consent during his/her lifetime for the posthumous removal of organs or such permission is granted by his/her relatives after the person’s death. Posthumous donors cannot be those who died in combat zones, orphaned children, unidentified persons, as well as prisoners.

It is also absurd to claim that conflicts in countries where cases of “transplant tourism” are recorded are organized precisely to make this tourism possible. The primary reasons for the armed conflict in Kosovo were the policy of ethnic discrimination by the Serbian government. In the 1990s, a series of Yugoslav wars began between the countries of the former Yugoslavia (which included present-day Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Slovenia). Accusations by the Kosovo Liberation Army of harvesting organs from soldiers and their subsequent resale have not been confirmed.

In 2013, the Revolution of Dignity began in Ukraine, provoked by the then government’s change from a European course of development to a pro-Russian one. Later, an anti-terrorist operation was launched in eastern Ukraine in response to the mass infiltration of armed Russian terrorist groups into the eastern regions and their seizure of local government bodies. At that time, Russian propaganda began spreading fake news about the illegal removal of organs from deceased soldiers. The European External Action Service’s EUvsDisinfo project explains that the accusations of organ trafficking in Ukraine are based not on facts but on pure speculation. There is no evidence of such activity outside pro-Kremlin media.

This information piece was produced with the assistance of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), provided on behalf of the people of the United States of America. This article’s content, which does not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the United States Government, is the sole responsibility of Deloitte Consulting under contract #72012118C00001.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations