At first sight, you may think that the unprovoked aggression by Russia against Ukraine is somewhat remote to Latin America. But taking a few seconds to think about the connections reveals that it is of critical importance, not only because of the economic consequences, good or bad (they are different for different countries), but also because of the potential impact on ideas and political support for non-democratic regimes in the region. Surprisingly, Latin America also has something to offer to help Ukraine turn the tide in its favour. Let’s analyse each of these issues in turn.

Economic implications

The economic implications of the Ukraine war for Latin America have multiple dimensions, but the most important channels operate through commodity prices, the disruption of trade flows, the monetary policy responses of developed countries, and the eventual impact on the multilateral trade system that has served the world so well during the last 50 years.

The impact of these effects differs by country. Food importers (in Central America) have suffered from the increase in food prices, while food exporters (Argentina and Brazil) have benefited. The disruption of trade flows, particularly in energy products, has benefited countries with an ability to export energy (Colombia, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago). It could have benefited others, like Argentina, the country with the second largest reserves of tight gas in the world and the largest in per capita terms, or Venezuela, known for its large oil and gas reserves. Both these countries have more than enough to fully replace Russian gas for at least a few decades. However, this potential has not been fulfilled. In the case of Venezuela, its domestic disarray leaves it with no capacity to increase production and therefore means it is unable to respond to the changes in patterns of world demand for energy. Argentina has thwarted this potential gain itself by engaging in aggressive restructurings with the Paris Club and private bondholders in recent years, which have made foreign direct investment all but impossible. This may revert in the future, and Argentina remains the country with the highest potential to benefit from the retrenchment of Russia from energy markets. At the same time, it remains the country that can contribute most to the independence of Europe from Russian gas. If it manages to achieve this goal, it could represent a significant contribution to weakening the economic grip of Russia on Europe. This is the reason we argue that the region also has the potential to contribute to Ukraine’s cause.

The turmoil produced by the invasion, and the short-lived commodity spike, while not responsible for inflation in developed economies or able to influence the inflation rate in the medium term (inflation in these regions is determined by monetary policy, not by a relative price shock in one commodity, regardless of how important that commodity is), did add substantial volatility to inflation in the short run, perhaps accelerating a policy response that may otherwise have taken longer to occur. Fortunately, and contrary to the consensus view of an imminent and impending collapse in emerging market debt resulting from higher rates (Acosta-Ormachea et al. 2022, Pazarbasioglu and Reinhart 2022), the current increase in interest rates has had a muted effect on emerging market debt, probably due to two reasons. The first is that rates have increased but continue to be very low, if not negative, in real terms. The second is that a large share of emerging market debt is denominated in dollars and euros but issued at fixed rates. Inflation in the United States and Europe reduces the real value of this indebtedness. This stock effect is large and compensates for the flow effect of higher rates (Nair and Sturzenegger 2022).

Finally, it is still too early to gauge the impact of the war on multilateralism, but unfortunately, it seems realistic to argue that unless Russia is unconditionally defeated, multilateralism will not return to where it was prior to the conflict. Whether the world will be split into blocs or Russia will remain isolated, containing the damage mostly to the aggressor country, is still too soon to say. But one way or another, the reach of multilateralism will be limited, and so too will be its benefits.

Political effects

Beyond these economic effects, I also want to point to the potential impact of the war on the ideological debates in Latin America, and Russia’s clout in the region. To start, we should acknowledge that Latin America is probably the most anti-capitalist region in the world.

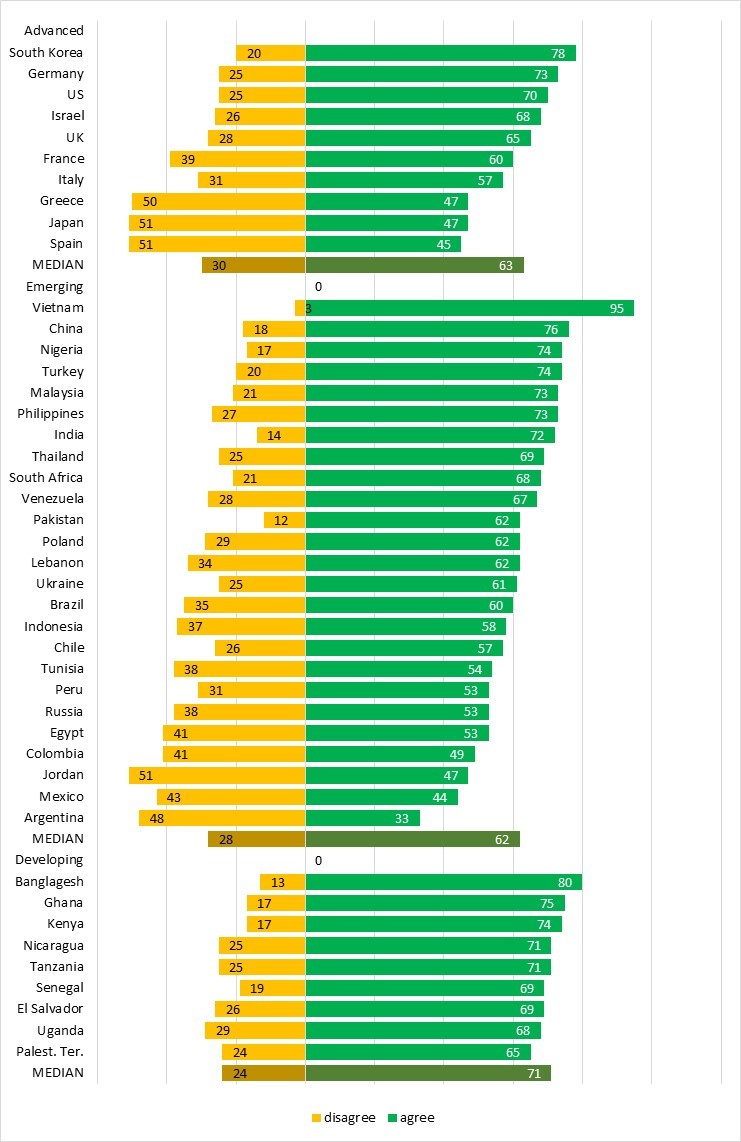

When asked by the Pew Research Center whether they agreed with the statement that “most people are better off in a free market system, even though some people are rich and some people poor”, the biggest disagreement with this statement among respondents occurs in Argentina, closely followed by Mexico (Figure 1). Within the group of emerging economies, Latin American countries seem to be in the middle half that is more hostile to capitalism (within this sample), with the exception of Venezuela (probably due to its own suffering under Maduro’s socialist policies).

Most people are better off in a free market economy, even though some people are rich and some are poor.

Figure 1. Support for Free Market System

Source: Spring 2014 Global Attitudes survey. Q13a. PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Latin American is the cradle of structuralism, and consistent with this view, it is a region where economic activity remains heavily regulated. In Liendo and Sturzenegger (2020), my co-author and I suggest four reasons for this. While they are not unique to Latin America, they reinforce each other. The first relates to the view on market economies mentioned above, which is the fuel on which the other reasons feed. In Latin America it is believed that if markets are not regulated, mischief will occur (firms will abuse customers, there will be exploitation of monopoly or oligopoly rents, and so on). There is, however, a vicious circle in this view. The more regulated an industry, the less competitive it becomes. The less competitive it becomes, the more it deviates from competitive behaviour, justifying yet more intervention. These dynamics strengthen and provide fertile ground for other reasons for intervention: the pressure of private sector interest groups (who tinker with regulations in their favour), the role of bureaucrats (who lobby for persistence of regulation that justifies its existence), and finally, because regulation always provides room for corruption.

What does this have to do with Russia’s unprovoked attack? Russia has built over the years significant political support in the region. The Argentinean president visited Moscow one week before the invasion and offered “Argentina as the beachhead for Russia’s landing in the region”. Mexico and Brazil, the region’s two behemoths, abstained from voting on the United Nations General Assembly Resolution suspending Russia from the UN Human Rights Council. Bolivia, Cuba and Nicaragua voted against. Venezuela, which has lost its right to vote due to payment arrears with the UN, urged a vote against. Brazil also shares the BRICS forum with Russia.

Russia has increased its influence in the region by providing support to mostly nondemocratic regimes in the region (Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua), and has tried to prop up its business ties (with a trail of corruption) in poor and cash-starved economies. Argentina, for example, in an incomprehensible decision, rejected an offer by Pfizer to provide 13 million Covid-19 vaccines in November 2020 in favour of a deal to buy Russian’s Sputnik vaccine. This delayed the vaccination process, at the cost of thousands of additional deaths (Urbiztondo 2021). Any version of Russian success in its unprovoked aggression will only help boost these negative effects in the region. In a region so prone to anticapitalism, such a result would significantly boost the influence of Russia in the region.

In sum, Russia must be defeated, not only for the sake of justice and because it was an unprovoked aggression that cannot be allowed to succeed, but also because of potential far-reaching negative effects around the world, including in Latin America on the other side of the globe.

References

Acosta-Ormaechea, S, I Goldfajn, and J Roldos (2022), “Latin America Faces Unusually High Risks”, IMF blog, 26 April.

Liendo, H and F Sturzenegger (2020), “A Practitioner´s Guide to Efficiency and Competition Policies in Banking Based on Argentina´s Experience, 2015-2019”, Working Paper No. 142, Universidad de San Andrés.

Nair, G and F Sturzenegger (2022), “The Global Distributive Impact of the US Inflation Shock”, HKS Working Paper No. RWP22-009

Pazarbasioglu, C and C M Reinhart (2022), “Perspectives on debt: Shining a light on debt”, Finance & Development 59(1).

Urbiztondo, S, (2021), “Vacunas contra el Covid: ¿cuántas vidas se salvaron y cuántas se perdieron?”, El Cronista, 15 June.

#helpUkraine_helptheWorld

This publication is a part of a collection of essays initiated by the National Bank of Ukraine. Famous economists, political scientists and historians, experts recognized in the world, volunteered to share their thoughts and arguments on why helping Ukraine is helping the world. The complete book of essays can be found via the link.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations