At the start of the full-scale war, Ukraine’s small and medium-sized businesses found themselves in an extremely difficult situation: markets were disappearing due to occupation, supply chains were collapsing, and demand was plummeting. In response, the government launched one of its largest support programs—Own Business. The idea was simple: to provide non-repayable microgrants to start or expand a business and thereby keep the economy afloat. Do these funds truly help businesses endure, how has the program evolved since its launch, and what improvements do entrepreneurs suggest?

Why microgrants matter

After the first few months of the war, many entrepreneurs were on the verge of closing due to a shortage of working capital, damaged production facilities, and the collapse of traditional supply and distribution chains. The Own Business program offered small grants—ranging from UAH 50,000 to UAH 250,000—that allowed business owners to repair workshops, purchase equipment, or build up raw material reserves. To receive more than UAH 75,000, applicants were required to create one or two jobs. If an entrepreneur fulfills the program’s conditions, they “repay” the grant through the taxes and fees they pay. If not, they must return the funds—a situation the author of this piece experienced personally, which became the reason for writing it.

The full analytical paper is available here.

It is significant that funds were available not only to existing entrepreneurs but also to those planning to start a business. This approach encouraged the emergence of new enterprises in places where they might not otherwise have appeared. By the end of 2024, more than 23,000 entrepreneurs had taken advantage of this opportunity, with the state investing UAH 5.5 billion in the development of their businesses. According to estimates from the Ministry of Economy, this created more than 40,000 jobs.

The Own Business program is designed to soften the economic impact of the war, prevent bankruptcies, and generate employment. Comparable tools have been used in other countries. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, OECD states provided grants to businesses, supported digitalization, and helped companies develop new skills (OECD, 2024). In the United States, grants were supplemented with tax incentives for small and medium-sized enterprises (SBA, 2022).

So, did grant support help businesses adapt to wartime conditions and become more resilient? I understand business resilience as the interplay of three components:

- Adaptation—the ability to respond quickly to shocks.

- Financial viability—the resources to cover expenses and invest.

- Organizational resilience—the capacity to restore or even expand operations after a crisis (Saad et al., 2021).

This study draws on several data sources: official statistics from the State Employment Center (SEC) dashboard; aggregated SEC data provided through an official request; ten in-depth interviews with entrepreneurs (five grant recipients and five non-applicants); four expert interviews (with representatives of a consulting firm and a civic organization); and my own experience applying for a grant.

What the numbers say

Program scale and coverage are growing

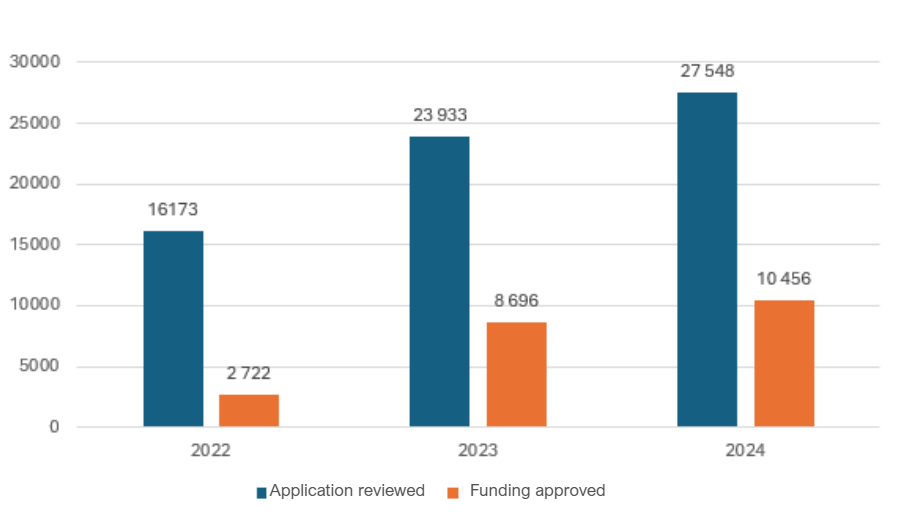

Overall statistics show that the number of program participants continues to rise (see Figure 1). In 2022, entrepreneurs submitted more than 16,000 applications, of which nearly 3,000 received grants. In 2023, the number of applications increased to 24,000, and in 2024 it surpassed 27,000. The share of successful applications also grew—from 17% in 2022 to 38% in 2024. This reflects improvements in the quality of submitted business plans as well as more effective program administration. The total value of awarded grants rose from UAH 640 million in 2022 to UAH 2.5 billion in 2024. In just the first four months of 2025, grants already amounted to UAH 739 million.

Figure 1. Number of applications submitted and grants awarded, 2022–2024

Source: State Employment Center data

Among grant recipients, women predominate while IDPs are underrepresented

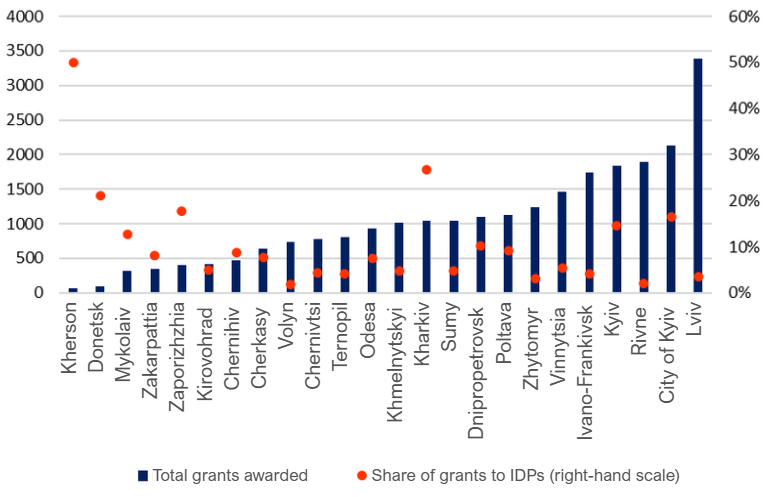

The share of women among grant recipients rose from 42% in 2022 to 55% in 2024 and 58% in 2025. Internally displaced persons (IDPs) from temporarily occupied territories accounted for only 8% of all awarded grants. Their share, however, varies considerably across regions—from just 2% in Volyn to as high as 50% in Kherson (see Figure 2). In frontline regions, the number of applications is much lower, likely reflecting both weaker overall business activity and more limited access to the program. In 2025, the government sought to respond by increasing grant amounts in these regions, but this step has not fully addressed the issue of accessibility.

Figure 2. Total grants awarded (2022–April 2025) and share of grants to IDPs, %

Source: State Employment Center data

Women entrepreneurs and internally displaced persons are more likely to face barriers in accessing capital and the labor market. For them, participation in the program represents not only financial support but also an opportunity for social integration and for strengthening their role in local communities. International experience shows that investing in vulnerable groups generates a multiplier effect: reducing unemployment, stimulating local demand, and fostering social cohesion (OECD, 2024).

Most grants go to trade and HoReCa

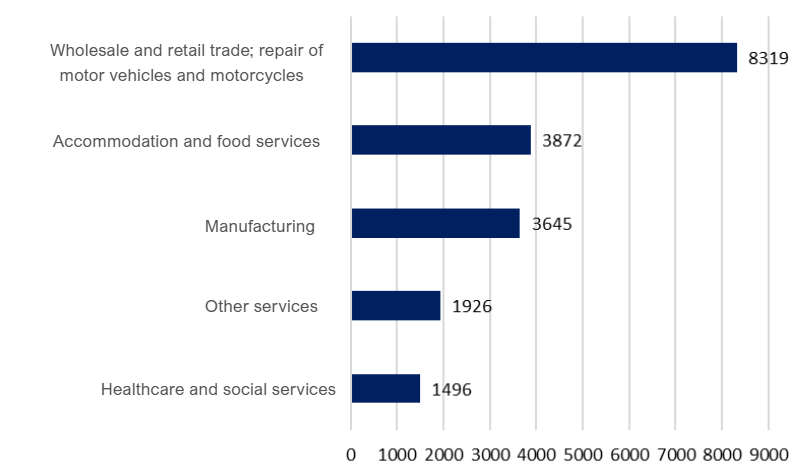

The largest share of grants has gone to entrepreneurs in trade and in accommodation and food services, with manufacturing in third place (see Figure 3). Several experts we interviewed noted that in higher-risk sectors—such as agritourism or innovative startups—the share of successful applications was lower, as many business plans were deemed “unrealistic.”

Figure 3. Top 5 sectors by number of microgrants awarded (2022–April 2025)

Source: State Employment Center data

How do grants help entrepreneurs? Findings from in-depth interviews

Grants provided stimulus and support

Most entrepreneurs who received a microgrant described it as a decisive boost. One respondent, who opened a building materials store, emphasized: “This grant really helped—I bought goods, did some renovations, even had enough for a sign. On my own, I wouldn’t have launched this quickly.”

Others noted that the grant enabled them to rent premises, purchase equipment, or immediately move their business online. For most, it made it possible not only to launch operations but also to adapt to wartime conditions.

In many interviews, entrepreneurs highlighted not only the economic but also the emotional dimension. The owner of an online English school explained: “It gave me the feeling that someone was supporting me. After everything we went through, this support carried not only financial but also moral weight.” Several participants described the grant as a signal that growth is possible even in wartime—something that genuinely helps sustain faith in the future.

But some entrepreneurs lacked knowledge

Everyone who went through the program mentioned the difficulty of applying—particularly filling out the questionnaire or preparing a business plan. One respondent, an entrepreneur who opened a coffee shop, remarked: “The hardest part wasn’t implementing the idea, but navigating the entire bureaucratic process. Fortunately, I had someone to help, because on my own I wouldn’t have managed.” Some entrepreneurs hired private consultants (grant writers) to avoid mistakes. This created a degree of inequality, since those with access to professional support had a greater chance of success.

Another critical issue was education and mentoring. Some respondents admitted that after receiving the funds, they did not know how to use them effectively. Participants without an economics background often spent money on equipment that failed to generate profit or underestimated future tax obligations. An expert from a consulting company emphasized: “A financial start without developing competencies is a step into the abyss of instability. People take funds without understanding how to manage them.” In some cases, entrepreneurs were required to return their grants when they were unable to meet the program’s conditions.

Key challenges of the program

Complicated application process and non-transparent selection

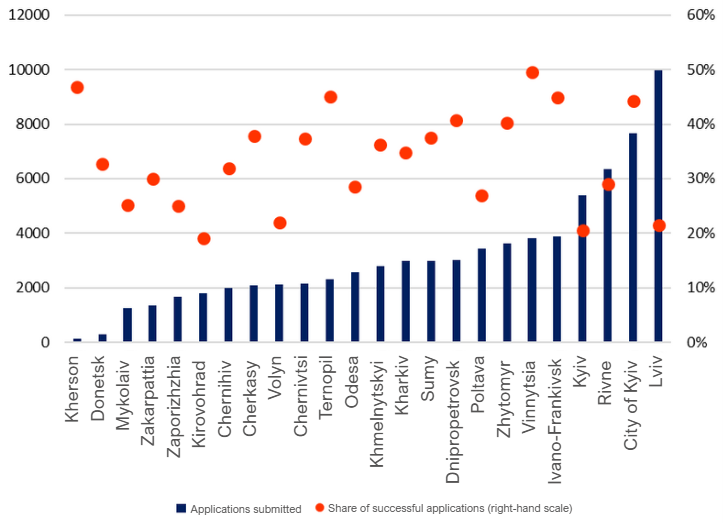

Entrepreneurs from frontline and remote areas submitted fewer applications and had lower success rates (see Figure 4). The reasons lay not only in the dangerous environment but also in weak digital skills, limited information, and the absence of reliable communication channels. Oleksandr, a farmer from the Zaporizhzhia region, remarked: “We are the ones who need support the most, but submitting an application is a whole quest.” He suggested simplifying the procedure for such regions or establishing mobile advisory centers.

Figure 4. Number of applications submitted and share of successful applications (2022–April 2025)

Source: State Employment Center data

In addition, entrepreneurs emphasized the need for clear and detailed feedback: an explanation of why their business plan was rejected and what specific mistakes they made. Rejection notes often sounded overly formal—for example: “questionable business plan results.” Sometimes the commission did provide additional explanations, but these were not always sufficient. One such case involved the author of this study, who received a rejection over a purely technical detail: in the business plan template downloaded from the SEC website, the formatting shifted during editing and two Excel cells ended up “the wrong color.” Situations like this create an impression of excessive bureaucracy and undermine trust in the program.

At the same time, it is important to note that rejection is not final: applicants can resubmit after correcting mistakes. In such cases, transparent and substantive feedback becomes a valuable tool that increases the chances of success on the next attempt.

Lack of mentoring and non-financial support

Almost all respondents noted that the program lacks a mentoring component. Entrepreneurs need training in accounting, marketing, and human resource management—particularly when they are becoming employers for the first time. In many Western countries, grants are often paired with mentoring and advisory services, which makes support more effective. For example:

- ”10,000 Small Businesses” by Goldman Sachs (USA, UK, France). A free 12-week program developed by Babson College, it does not provide grants directly but instead teaches financial management, marketing, leadership, and business planning, while offering entrepreneurs mentors and helping them build networks. According to program administrators, 67% of graduates increased revenues and 44% created new jobs within six months of completing the program. This suggests that an intensive educational component can substitute for direct financing and deliver sustainable results.

For Ukraine, the lesson is to create a “full cycle of support”: not only funding, but also training, networking, and mentorship. Such an approach would strengthen the prospects for business growth in the future.

- UnLtd (United Kingdom). This foundation supports social entrepreneurs by combining financing with individual mentoring, leadership development, and access to partner networks. On its official website, UnLtd states that its grants are “designed around you,” and support includes one-to-one coaching, mentoring, and free expert assistance. The goal is for every grant recipient to receive not only funding but also personalized services to overcome challenges and grow effectively. For Ukraine—where the Own Business program is actively used by women and internally displaced persons as a tool of adaptation—such an approach could be especially valuable.

This example is particularly relevant in the context of reconstruction: social entrepreneurship in Ukraine can simultaneously address economic and social challenges. Grants combined with mentorship foster sustainable business models that benefit not only business owners but also local communities.

- The Croatian Experience (2010–2012). Research by Srhoj, Lapinski, and Walde (2021) showed that Croatia’s grant program improved the survival and growth of small businesses, but the effect was stronger for those who also received consulting. The absence of such support reduced the long-term impact. This offers another argument in favor of combining financing with mentorship.

Ukrainian experts emphasize a similar point: for long-term resilience, grants must be part of a comprehensive support ecosystem. In-depth interviews likewise showed that without complementary support, some businesses quickly fall back to mere “survival” mode.

It is also important to track what happens to Ukrainian grant recipients after one, two, or five years. Such data would make it possible to assess the program’s impact and effectiveness and adjust it accordingly. Unfortunately, systematic, long-term monitoring of program outcomes does not yet exist. Still, our research allows us to formulate certain recommendations.

Policy recommendations

- Simplify the grant application process and strengthen communication. Submitting an application should be no more difficult than applying for a bank loan. To achieve this, training—such as an online course—on how to prepare a proper business plan should be available to all applicants. It is also important to introduce a feedback mechanism so that applicants understand exactly what needs improvement.

- Expand financial capacity and grant flexibility. The maximum grant amount should be raised to UAH 500,000, as current limits do not account for inflation or the needs of businesses that create additional jobs. At present, this amount is available only in certain regions, but it should be made accessible nationwide. At the same time, entrepreneurs should be allowed greater flexibility in spending—adjusting budgets, replacing equipment, or purchasing alternative goods when new circumstances arise. This would reduce bureaucratic barriers and improve the efficiency of funds.

- Introduce mentoring programs. Grants should be accompanied by consulting in accounting, marketing, and HR through online courses, seminars, and other formats. For veterans and IDPs, separate programs should be developed to reflect their specific psychological and social challenges.

- Improve transparency in selection and feedback quality. The commission should publish evaluation criteria and, after the selection process, send applicants detailed comments on their applications. Such systems already operate in many European countries and help build trust in the program. Own Business does provide feedback, but it is often only formal.

- Create regional and sector-specific packages. Farmers, IT startups, and coffee shops require different grant conditions because they face different production cycles, capital payback periods, and risks. For frontline regions, higher grant amounts and/or insurance should be provided, given the greater likelihood of property loss.

- Establish monitoring and data collection. To assess long-term effectiveness, mandatory annual reports from grant recipients should be introduced, along with tax and turnover data from the State Tax Service. This would make it possible to evaluate whether businesses are growing, jobs are being created, and funds are returning to the budget.

How the state is changing the program in 2025

After this research was completed, the government announced a series of program updates. Beginning in 2025, the list of eligible recipients was expanded: grants are now available to producers of still wines and honey-based beverages. Another bank—PrivatBank—joined the program, giving entrepreneurs the option to choose between it and Oschadbank.

For veterans and their spouses who receive a grant, the project implementation period has been extended: instead of the standard three years, it may now last five or even seven. Grant repayment continues to take the form of taxes and fees paid during this period. In addition, veterans who successfully complete a project and “close” a grant have gained the right to submit one additional grant application.

The size of microgrants remains in the range of UAH 50,000–250,000, but applicants under 25 can receive up to 150,000 without the mandatory requirement to create jobs. The most significant innovation is the introduction of grants of up to UAH 1 million for combat veterans, persons with disabilities caused by the war, and their spouses. For amounts above UAH 500,000, however, co-financing is required: 70% provided by the state and 30% contributed by the entrepreneur. In addition, applicants must have been registered as sole proprietors (FOPs) for at least 12 months prior to applying.

The government has also taken into account the needs of frontline regions. Previously, grants of more than UAH 250,000 were available only to veterans and their spouses (subject to co-financing). Now, entrepreneurs from eight frontline regions can receive up to UAH 500,000. The key requirement remains the same—to create at least two jobs. This is an important signal of support for businesses in high-risk areas, since it is there that entrepreneurs face the greatest challenges.

These changes indicate that the government is seeking to better align the program with the needs of different categories of entrepreneurs. We hope this research will contribute to improving the program.

Expert perspectives and international experience

In the course of this research, we interviewed representatives of think tanks and civil society organizations working with entrepreneurs. Experts emphasized that microgrants should be embedded within a broader ecosystem of entrepreneurship support. This means that financial aid must be complemented by training, consulting, and scaling tools—for example, the option to obtain a second grant or a preferential loan to expand operations (currently, only veterans and people under 25 are eligible to reapply for a grant). In OECD countries, grant programs are often delivered through digital platforms that allow beneficiaries to track progress, receive mentoring, and connect to new markets.

For instance, OECD research (2024) shows that grants are most effective when recipients simultaneously participate in digitalization courses—such as launching online stores, automating accounting, or adopting cashless payment systems. This approach can raise small-business productivity by 20–25%. In Ukraine, similar training workshops have been organized sporadically by civil society groups but have not been integrated into the Own Business program.

Experts also cautioned against the risk of dependency: if the state distributes grants annually without clear growth criteria, businesses may become accustomed to “easy money” and stop pursuing market opportunities. Research by Durst and Gerstlberger (2020) finds that long-term support without guidance and oversight can foster a “grant-seeker culture,” where entrepreneurs continuously apply for new programs but fail to build genuine resilience. For this reason, grants should be linked to obligations such as scaling up, attracting private investment, or entering export markets.

At the same time, Own Business is not the only instrument of state support. Other measures include preferential loans (the “5–7–9%” program), partial compensation for Ukrainian-made equipment, and more. Many of our respondents combined several forms of support—for instance, using a grant for equipment, a loan for working capital, and applying to local programs. Stronger coordination among these initiatives is therefore needed: when entrepreneurs apply to one program, they should also be informed about other available opportunities.

A comparative view: recipients vs. non-recipients

An interesting part of the study is the comparison between those who received a microgrant and those who did not (and did not apply). The latter more often focused on keeping their businesses at the current level and avoiding risks. Ivan, the owner of a workshop in Vinnytsia, said: “The main thing is to hold on. Now is not the time for expansion.” Anzhelika from Kropyvnytskyi added: “This isn’t the time to grow. We need to survive.” Those who did not receive a grant usually improved their business plans, cut costs, and postponed scaling “until after the victory.”

Grant recipients, by contrast, demonstrated a bolder approach: expanding product lines, opening new outlets, and moving into online sales. According to them, it was precisely the presence of a “financial cushion” that made it possible to take risks. Oksana from Poltava, who opened a workshop producing military uniforms, admitted: “If not for the grant, I wouldn’t have dared. Now we have six people working, and we’re looking for ways to enter export markets.” This comparison illustrates how limited access to capital can be during wartime—and how a single program can alter the trajectory of a business.

Limitations and potential for further research

This study has several limitations. First, there is a lack of data—for example, information on whether businesses developed or closed a year or more after receiving a grant, or on their profitability. Second, the sample size: ten in-depth interviews constitute an exploratory format and are not intended to be representative. Nevertheless, these narratives reveal details that are often lost in statistical reporting.

The study also opens space for further analytical inquiry. Future projects could rely on entrepreneur surveys and financial reporting data to track changes in income, employment, and productivity. Experimental methods—such as randomized grant assignments—could help assess the causal effects of microgrants. It would also be worthwhile to study how grants interact with other programs, for instance, whether participation in the “5–7–9%” loan program increases the likelihood of success among grant recipients. Taken together, such approaches would help inform the design of a more comprehensive policy for supporting small businesses.

Conclusions

For many entrepreneurs, microgrants have served as a lifeline in a critical moment. They have enabled not only survival but also the launch of new projects, the creation of jobs, and the support of local economies. Grants also encourage entrepreneurs to look beyond immediate challenges and to plan for the longer term.

At the same time, while grants can strengthen business resilience, they do not guarantee it. The decisive factors lie in the accompanying conditions—knowledge, guidance, and an environment of trust. The changes introduced to the program in 2025 expand opportunities for certain groups of entrepreneurs and take into account lessons from previous years. Yet the main lesson remains: without effective mentoring, even the most generous financial support may fail to deliver sustainable results. This should be borne in mind when reforming the program and when launching new support instruments.

Own Business has the potential to become not only an anti-crisis tool but also a cornerstone of Ukraine’s economic recovery strategy. To realize this potential, the state must listen to entrepreneurs, refine the rules, and support those who are willing and able to create jobs.

References

- Aldianto, L., Anggadwita, G., Permatasari, A., Mirzanti, I. R., & Williamson, I. O. (2021). Toward a business resilience framework for startups. Sustainability, 13(6), 3132.

- Audretsch, D., Momtaz, P. P., Motuzenko, H., & Vismara, S. (2023). The economic costs of the Russia-Ukraine war: A synthetic control study. Economics Letters, 224, 111123.

- Durst, S., & Gerstlberger, W. (2020). Financing responsible small-and medium-sized enterprises: An international overview of policies and support programmes. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(1), 10.

- Kersten, R., Harms, J., Liket, K., & Maas, K. (2017). Small Firms, Large Impact? A systematic review of the SME Finance Literature. World Development, 97, 330–348.

- OECD. (2024). Enhancing resilience by boosting digital business transformation in Ukraine. OECD.

- Srhoj, S., Lapinski, M., & Walde, J. (2021). Impact evaluation of business development grants on SME performance. Small Business Economics, 57(3), 1285–1301.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2024). Assessment of the Impact of the War on Micro-, Small-, and Medium Enterprises in Ukraine.

- Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. Resolution No. 738 of June 21, 2022, “Certain Issues of Providing Grants to Businesses.”

- State Employment Center of Ukraine. Dashboard with data on the Own Business program (2022–2025).

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations