For a long time, globalization was seen as the triumph of mythologized neoliberal forces. Reforms aimed at dismantling administrative constraints on the economy and reducing the role of government were accompanied by major shifts in the principles of macroeconomic policy: monetary policy came to focus on price stability, while fiscal policy centered on the business cycle.

It quickly became clear that a macroeconomic regime compatible with globalization required revisiting the institutional principles underpinning central banking. Central bank independence became a symbol of the renewed role of the state in the economy, a source of expectations of macroeconomic stability, and of technocratic approaches to economic policymaking.

Today, the experience of the transformations of the 1980s and 1990s—known as first-generation structural reforms—feels like a distant echo of a past in which the forces that opened the path to global integration had a positive impact on strengthening central bank independence. Yet the crises of the era of global economic expansion and the revival of right-wing conservative currents in the politics of many countries raise a key question: have the forces that supported central bank independence during the first generation of structural reforms reversed? Has the momentum behind strengthening central bank independence been lost in an environment increasingly shaped by a mix of populism, isolationism, and brutal unilateralism in international relations, alongside the search for a new path for the survival of a global economy already undermined by geoeconomic fragmentation and geopolitical distrust?

While there is a temptation to characterize the recent surge in pressure on central banks as a revival of right-wing populism, note that such pressure has always existed. What has changed are its form, its drivers, and its discourse. To better understand the intensity of the current moment, it is therefore necessary to examine the strengthening of central bank independence as a global trend, as well as the evolution of pressure on monetary institutions.

Central bank independence and inflation in the global economy

The revival of global integration is traditionally dated to the second half of the 1980s. The world entered this period with a strong aftertaste of recent inflation, the scale of which had shocked many advanced economies (Figure 1). The rest of the world was recovering from both the inflationary legacy of the previous decade and a depressive external debt crisis. The search for new growth drivers was evident, as was the need to stabilize inflation. Trust in monetary policy was so weak that even radical central bank measures to stabilize prices failed to produce rapid results, slowing growth. The early 1990s brought an inflationary relapse. However, advanced economies had already begun to develop immunity to price pressures (Figure 1). The benefits of monetary policy focused on inflation control became clear. Following favorable shifts in the academic sphere, change also reached the political arena. Central bank reforms began worldwide.

Figure 1. Global inflation (%)

Source: World Bank data

Advanced economies set the trend toward strengthening central bank independence. Much of this was linked to the creation of the European Union and the euro area, membership in which required sweeping updates to national central bank legislation built around mandates of price stability and political, economic, and financial independence. The blueprint for strengthening central banks quickly became universal. Most reforms in emerging markets were driven by the need for institutional adaptation to an environment of global openness, as well as by lessons drawn from past inflationary trauma. As shown in Figure 2, reforms of monetary institutions became a worldwide trend.

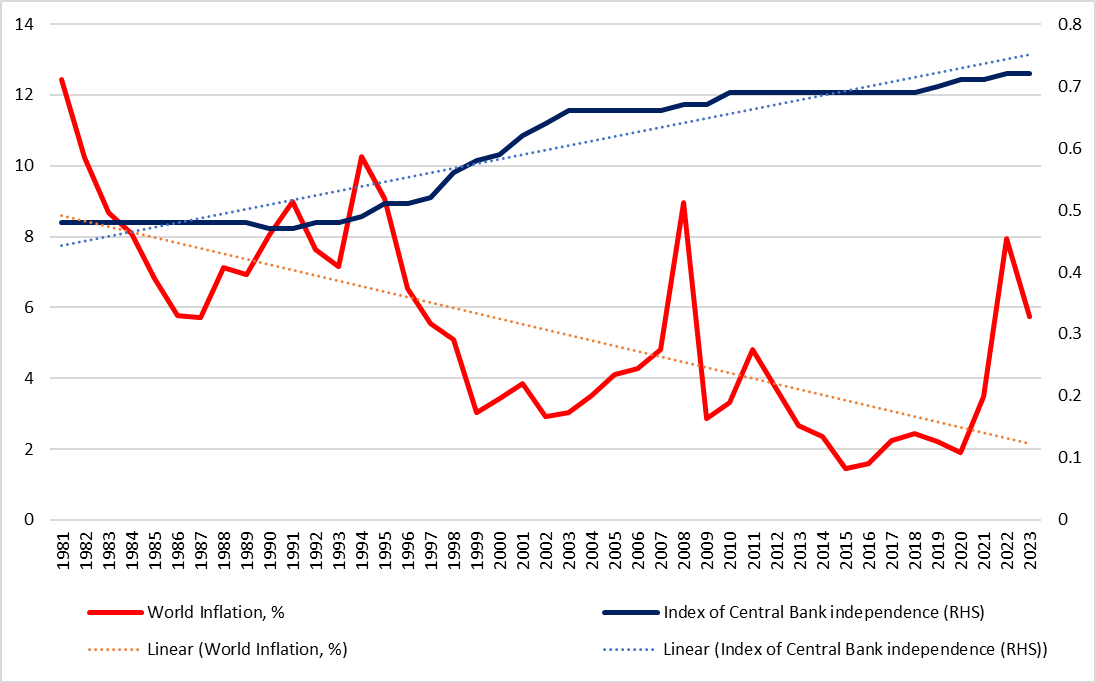

Figure 2. Global inflation (%) and central bank independence (index)

Source: Author’s calculations based on World Bank data and Romelli (2024). Note: Dashed lines indicate linear trends for the respective variables

Over nearly 40 years, the level of central bank independence worldwide has almost doubled. As Figure 2 shows, reforms aimed at strengthening monetary institutions were not an end in themselves, since trends in formal central bank independence and inflation move in opposite directions. Despite periods of accelerating inflation ahead of the global financial crisis and after the COVID crisis, overall price pressure worldwide has declined. This contrasts sharply with the period before the implementation of first-generation reforms. Moreover, although many emerging market economies continue to suffer from a typical set of institutional ailments—weak rule of law, informality, and political fragmentation—central bank reforms have been successful in most cases.

In recent years, no emerging market economies, except Argentina and Turkey, have experienced a major currency crisis or inflationary pressure substantially higher than elsewhere. The inflation gap between advanced economies and the rest of the world has also shifted. While this gap widened sharply during the 2008 global financial crisis amid gradual convergence in inflation rates, during the 2021–2023 inflation surge, both advanced economies and the rest of the world showed roughly similar trends. As a result, the inflation gap between them narrowed.

The plateau of central bank independence

Figure 2 also points to another conclusion: in recent years, progress in strengthening central bank independence has been much slower than in the 1990s. Thanks to Claudio Borio, Chief Economist of the Bank for International Settlements from 2013 to 2024, this phenomenon is known as the “plateau” of central bank independence. Indeed, aside from Brazil in 2021, there have been no major central bank reforms that significantly raised the aggregate index. What explains this plateau?

First, central bank independence increased in countries that implemented large-scale reforms. The main drivers were European integration and engagement in programs with international financial institutions, for which the status of monetary regulators became one of the key indicators of institutional capacity to deliver sustained macrofinancial stability.

Second, in many countries, formal reforms either did not take place or did not go far enough to significantly raise the index. For example, in a number of common-law countries, legislative changes governing central banks are extremely rare. In several inflation-targeting countries (such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, South Africa, and Thailand), change occurred at the policy level rather than through formal legislation. In these cases, greater transparency combined with well-developed inflation-targeting capacity signals progress far more clearly than in countries where reforms existed only on paper or were reversed in subsequent electoral cycles.

Third, the modality of relations between central banks and the political environment varies by regime type. In weak democracies or fragmented societies, reforms aimed at strengthening central bank independence are unlikely. Oligarchic economies also fail to generate reform momentum when competition for control over a central bank becomes an instrument to secure politico-economic advantage for certain business groups. The same applies to weak extractive autocracies, which are vulnerable to coups. In autocracies where price stability serves as a means of securing public loyalty, the professional autonomy of central banks is maintained through direct political patronage outside formal legislation, which may prescribe invariant levels of monetary institutional independence.

In resource-based economies where autocracy serves as a means of securing political control over the distribution of resource rents, mechanisms of macroeconomic stability are often built around the creation of substantial fiscal buffers that can smooth pressures on business cycles, inflation, and exchange rates arising from commodity prices, while also serving as a source of investment. Accordingly, central banks in such systems tend to focus more on managing external assets than on monetary policy.

Does this mean that the list of countries where further reforms to strengthen central bank independence remain possible is already too short? Perhaps. Yet we can also argue that in many countries that have already made progress in central bank legislation there is still room for adoption of best practices. Much of this reflects changes in academic understanding of the elements of central bank independence. While financial independence, accountability procedures, and aspects of corporate governance in central banks received less attention during the institutionalization of price stability mandates or exclusive control over monetary instruments, today, attention is largely focused on precisely these routine details. In other words, most changes to central bank legislation over the past decade can be described as best-practice tuning.

On the other hand, many of these procedural recalibrations in central bank legislation are also tied to shifts in political discourse. Traditional “discontent,” which feeds populism, has unexpectedly morphed into a right-wing conservative assault on independent regulators. Yet this discontent never disappeared, even during the reform-intensive 1990s. It evolved alongside the political landscape, which has come to include geopolitical fragmentation and changes in leadership over the maintenance of economic openness.

Globalization and the evolution of pressure on central banks

The need to conduct macroeconomic policy in an environment of rising capital mobility justified greater central bank independence. Price stability and institutionally independent central banks were seen as a superior alternative to unreliable nominal anchors such as exchange rates. Changing the nominal anchor required trust, which could be built through a clear separation between electorally sensitive fiscal policy and technocratic, non-electoral monetary policy, later augmented by responsibility for financial stability. At the same time, even amid the early successes of independent regulators, overt attempts emerged to substitute the achievements of monetary policy with impersonal drivers of disinflation (such as trade liberalization or structural reforms). These were presented as forces through which lower independence could be accompanied by lower inflation and better growth prospects.

In other words, global integration generated opposing forces. On the one hand, central bank independence was framed as a form of institutional adaptation to external shocks and reduced vulnerability. On the other hand, it was portrayed as a source of automaticity in restraining inflation, implying that the socially optimal level of independence might be lower. How dangerous this discourse was became clear very quickly. In 2008, global commodity prices reached unprecedented levels. On the eve of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, it became evident that accelerating inflation signaled global overheating—and that viewing globalization as a mechanical shield against inflation could not withstand scrutiny.

The global financial crisis and the era of quantitative easing triggered a wave of distrust toward the entire regulatory perimeter and its institutions. If calls for rate cuts were once routine, how could such demands persist when rates were already near zero? New approaches to banking regulation came under the same kind of pressure that had traditionally been directed at interest rates. In the United States, the easing of banking regulation a decade after the introduction of Basel III “unexpectedly” culminated in the 2023 “crypto spring” (the collapse of several banks related to the crypto industry). Meanwhile, the redistributive effects of quantitative easing, as well as more visible benefits of supporting asset prices relative to the less obvious gains for labor markets, solidified a new discourse of pressure. Central bankers increasingly came to be seen as a kind of areopagus of the global elite. Monetary policy was ever more sharply criticized for its focus on asset markets, even though just before and after the COVID crisis, virtually all advanced economies experienced unprecedented declines in unemployment.

It is no coincidence that the assault on the global economy and the erosion of the rules-based international system have subsumed right-wing populist pressure on central banks. Beyond outright autocratic attempts to subordinate regulators, pressure on central banks is taking on a new dimension. If global fragmentation is the new reality and deglobalization continues to accelerate under geopolitical tension, arguments for central bank independence rooted in the need to counter destabilizing capital flows may appear increasingly unconvincing.

Why shouldn’t loose monetary policy offset the losses associated with adapting to the retreat of globalization? Remilitarization and efforts to assert strategic autonomy inevitably carry fiscal consequences. And with large accumulated debt burdens, even well-grounded anti-inflationary warnings from central banks can turn into triggers for confrontation. It is therefore unsurprising that the inflation–unemployment tradeoff (the Phillips curve)—a perennial tool of political manipulation—has been pushed into the background.

Where low inflation once implied higher unemployment and vice versa, it is now associated with higher levels of innovation. Low inflation implies low interest rates, which in turn support rising valuations of technology companies, enabling them to invest in innovation, thereby reinforcing monopoly positions and boosting profits. Thus, whereas governments once pressured central banks to “let inflation run” in order to reduce unemployment, today technocratic elites have incentives to demand low inflation and low rates. In both cases, citizens bear the long-term costs of such policies.

How should central banks respond?

The answer, of course, depends on the balance between market and social forces that require price and financial stability, as well as on how closely the political agenda aligns with the rule of law. When autocrats undermine the rule of law, the question of institutional independence becomes a question of the symptoms of democratic frustration. Where conditions are less bleak, the optimal course of action should rest on the principles of transparency, consistency, and flexibility.

Global fragmentation increases the likelihood of prolonged and previously unseen supply-side shocks. Under such conditions, the role of price stability as a nominal anchor only grows. This actualizes the question of regulators’ professional competence. Hardly anything can substitute for well-grounded decisions on monetary policy instruments or measures to ensure financial stability.

Politically motivated decisions quickly reveal themselves through incompetence and misalignment with market conditions. Central bank independence must increasingly be positioned as the foundation for professional and socially oriented decision-making. The importance of communication has never been greater. Clearly articulated communication about the broad societal benefits of central bank independence and about narrowing the space for biased perceptions of political capture may now be one of the most important ways to build institutional trust. Trust and inflation expectations are inversely related. Improving inflation expectations is therefore essential for responding more flexibly to shocks, thereby leaving greater room for structural adaptation to new global transformations.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua/

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations