Drawing on the statistical and survey data, this blog suggests a causal relationship between church competition and religious participation of Ukrainians in terms of religious affiliation, church attendance, subjective religiosity, and praying at home.

Introduction

On April 23 2016, President Poroshenko emphasized the importance of establishing one local Orthodox Church. Paradoxically, this move may cause a decrease in average religious participation among Ukrainians. How is it possible? Stemming from a research working paper, this blog suggests that church competition between Orthodox groups has been a driver of religious participation among Ukrainians.

Ukrainian religious groups have been quite competitive. In different years various groups seized buildings of each other, litigated, and struggled politically. The Bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church even anathematized the head of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Kyivan Patriarchate (UOC-KP) in 1997. In some cases, Ukrainian citizens have participated in these processes by all means at their disposal. In 1999 a Maryupol’s activist faced Patriarch Filaret (Denisenko) and “emptied a bucket of ‘holy’ water over his head and then started to beat him over the head with it”.

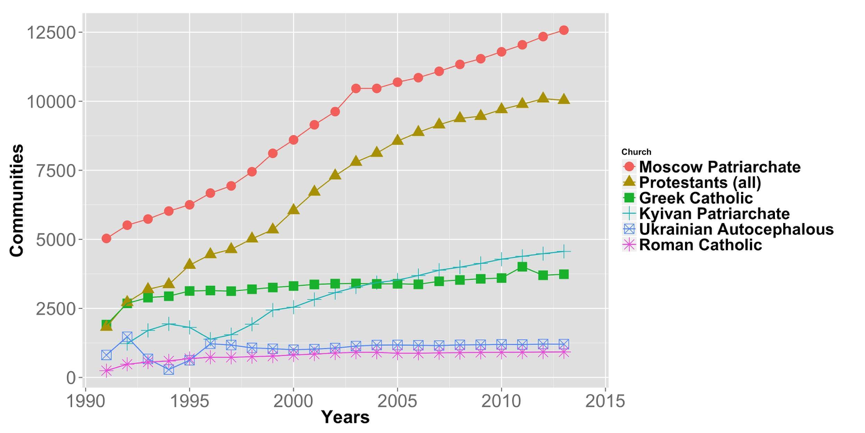

Furthermore, Crimean annexation and the ensuing hybrid war brought about new, previously unseen, levels of religious persecution. A leader of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) Alexander Zakharchenko publicly stated that he acknowledges only Moscow Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, Islam, and Judaism and promised to fight “sectarianism” and “pseudo-religions”. A usual suspect for “sectarianism” in this case is the Protestant church. According to the Institute of Religious Freedoms, troopers of the self-proclaimed DPR kidnapped and physically assaulted a number of Protestants in such cities as Donetsk, Gorlovka, Shakhtarsk, and Druzhkovka (IRF, 2014). A nuanced reader, however, may also interpret the speech of Zakharchenko as an attack on Greek Catholicism and those Ukrainian Orthodox churches that do not act on behalf of the Moscow patriarchate. Such confrontations influenced the attitudes of Ukrainians towards the Churches and their role in the society. A new trend of the hostility towards the Moscow patriarchate has emerged. According to the recent surveys conducted in 2015, 19 per cent of respondents agreed that the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) is the “church of the state-aggressor that carries out harmful activities”. Moreover, around 50 Orthodox communities changed their affiliation from the Moscow patriarchate to the Kyivan patriarchate since 2014. This number is relatively small (50 communities out of more than 12,000 communities constitutes less than one per cent). Nevertheless, these conversions stroke experts and members of the public (Figure 1).

Church competition theory

Churches and church competition in Ukraine have been studied extensively. However, to my best knowledge, there has been no attempt to study possible consequences of church competition in Ukraine with regard to the average religiosity of people. A link between church competition and religious vitality in a society has been a subject of heated debates in Sociology of religion. The original theory of church competition was developed in the US in order to explain high levels of religiosity in this country. According to this theory, a competitive religious market might be a powerful source of religious vitality in a society. Competition is important because of the two reasons: (1) various churches can better match the potential religious preferences of people, thus creating adequate niches; (2) competition provides additional incentives for churches to fight for their congregation instead of acting as “lazy firms”. Being applied successfully for the US, this theory, however, has been challenged in other countries. Comparative studies have shown that church competition does not have uniform effects and depends on many other factors. One of the arguments of this working paper is that specific within-Orthodox competition that exists in Ukraine has positively and significantly affected religious participation of Ukrainians.

Religious communities and within-Orthodox competition

Previous studies have often employed surveys to measure church competition, which has biased the results considerably. Therefore, a new dataset of religious communities was collected for the purpose of the present study. Although similar data have been employed before, this dataset allows better cross-regional comparison. Figure 2 shows the estimated numbers of religious communities (total) in Ukraine from 1991 to 2013.

Figure 2. Religious communities (estimated) on the country level. Ukraine, 1991-2013

Note: Estimated by the author, details available on request

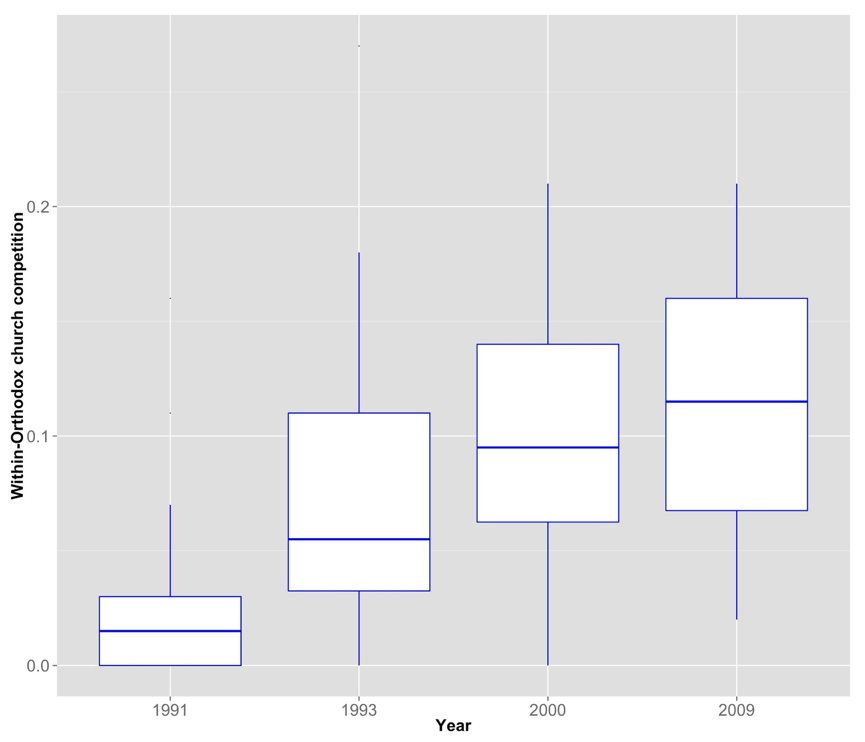

These data on the regional level were employed in order to construct an index of within-Orthodox church competition in each region. This index was calculated in two steps. First, an inverse of Herfindahl index was calculated based on the shares of churches. In this way 0 indicates absolute concentration, and 1 indicates absolute competition (which is, perhaps, the most traditional measurement in Sociology of religion). Then, the counterfactual rates of church competition were calculated, which would have been observed if the Ukrainian Orthodox churches were united (in line with words of Mr. Poroshenko). In other words, a hypothetical situation was simulated when all Orthodox shares were summed together as the share of the united church. A new Herfindahl index was calculated with this new “united” church. A difference between the real and counterfactual Herfindahl indexes shows to what extent church competition in Ukrainian region has been driven by the Orthodox Churches. Figure 3 plots the respective values from 1991 to 2009. As can be seen, the median value increased in the course of time.

Figure 3. Within-Orthodox church competition in Ukrainian regions

Note: Estimated by the author, details available on request

Church competition and religiosity

Does the competition between Orthodox groups influence the average religiosity of Ukrainians? Two more datasets are employed here in order to answer this question. The first one is a dataset pooled from the surveys conducted by the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine (ISNASU) from 1992 to 2006. The second one is the European Social Survey (ESS) conducted in 2012. These surveys employed different questionnaires and sample designs, which assures the robustness of findings. Religious participation is measured by four different variables. The ISNASU surveys provide information about church affiliation (dummy). The ESS survey provides information about subjective religiosity, church attendance, and praying at home.

Results of the statistical analysis

All the statistical models have revealed significant and positive influence of within-Orthodox church competition on the religious behavior of Ukrainians in terms of affiliation, subjective religiosity, church attendance, and praying at home. The relationship remains intact after controlling for a a battery of independent variables on the individual and contextual levels, including individuals’ language preferences, employment status, educational status, health status, loss of a partner status, gender, age; communist religious suppressions in a region, economic performance of a region, the level of unemployment in a region, and time after the collapse of the USSR.

Correlation or causality

Many papers have studied the correlation between church competition and religiosity. However, there are very few studies of a causal relationship between them. In order to address this issue an instrumental variable is employed here.

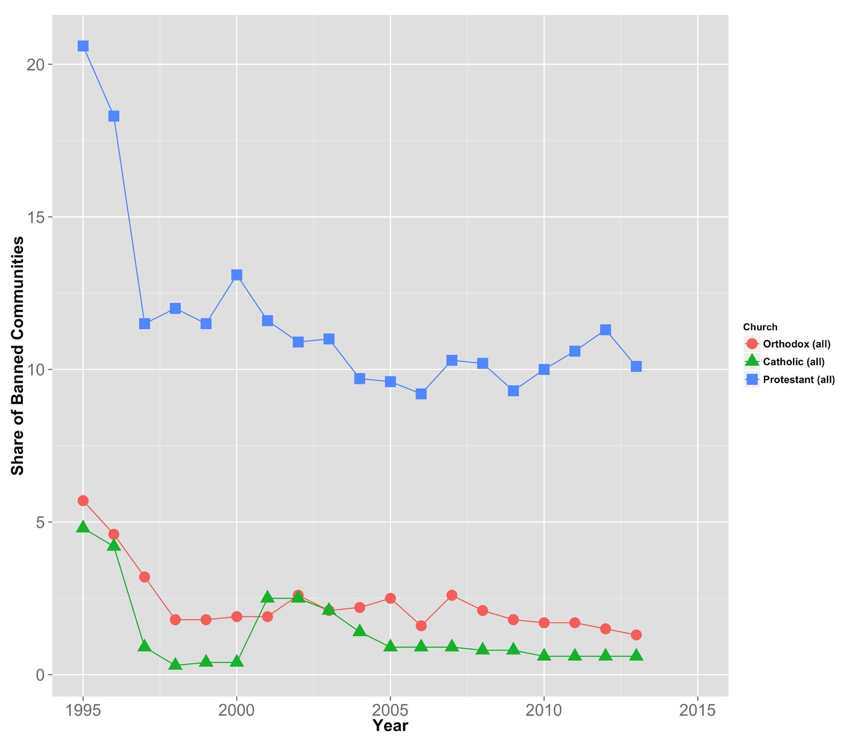

Figure 4. Share of not registered (rejected) communities on the country level (1995-2013)

Note: Estimated by the author, details available on request

Instrumental variable (IV) is a special measure that must affect the dependent variable only indirectly through the independent variable of interest. In this way a researcher makes sure that there is a one-way relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Therefore, it is necessary to find a variable that affects average religious behavior of individuals indirectly via church competition. The instrumental variable employed here is the share of all religious communities whose registration was rejected by the state. The state may reject a community’s registration (or cancel it) if the community’s ordinance does not comply with the Constitution of Ukraine. It was observed that the post-Soviet governments returned to the strong regulation of the religious markets in the 21th century in areas where one religious group constituted the majority of the population. Indeed, the IV has a strong negative correlation with church competition (-0.47). In other words, strong regulation decrease church competition. The IV does not correlate with the dependent variable (church attendance), thus fitting the necessary prerequisite. The results of the two-stage least squares procedure show that religious regulations indeed affect church attendance indirectly through church competition, suggesting that there is a one-way relationship between church competition and religious behaviour.

Summary and possible consequences of church competition and unification

Church competition theory is a highly debatable theory in Sociology of religion. According to this theory, average religiosity in a society increases when churches compete with each other. Ukraine offers a unique opportunity to test the effects of the competition within a single and yet competitive dogmatic religious group, i.e. Orthodox churches. A special index of church competition employed for a set of statistical models with different data sources and specifications show that church competition between Orthodox churches correlates positively with religiosity among people in terms of affiliation, church attendance, subjective religiosity and praying at home. Moreover, there are some indications that this link is causal. Going back to the President Poroshenko’s statement, the data suggest that the unification of the Orthodox Churches may actually lead to a decrease in religious behaviour among Ukrainians due to the decrease in church competition. Thus, the unification policy desired by part of Orthodox clergy, in fact, might yield a result that is quite unpleasant for them in the long run.

Acknowledgments: I am indebted to Stanislav Korolkov for his help in collecting data. I am also grateful to Yevgen Golovakha for granting the survey data.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations