To mitigate the consequences of the current global economic crisis, Ukrainian government should use well-known instruments: let the currency gradually depreciate while containing panic on the FX market, support banks and businesses that will suffer the most; provide financial support to the most vulnerable people; prepare the healthcare system for possible virus outbreak.

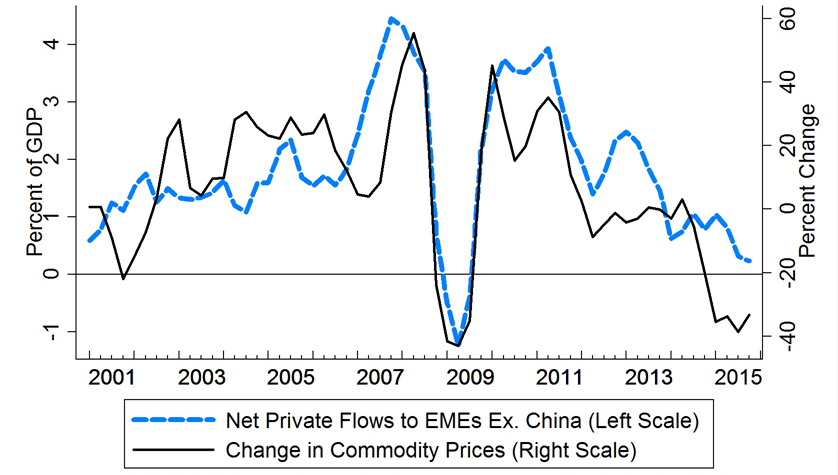

The global financial markets are in deep crisis and the current panic is very much reminiscent of the meltdown during the Great Recession of 2008-2009. Small open emerging economies reliant on commodity exports (e.g. Ukraine) are particularly vulnerable to such crises: not only the price and volume of exports fall but also capital outflows thus putting financial systems of these countries under enormous stress (see Figure 1). As a result, global crises tend to hit countries like Ukraine very hard. For example, Ukraine’s GDP contracted by 15 (!) percent in 2009.

While the banking sector enters the crisis in a much better shape than it did in 2009, the level of government debt is relatively low, and the National Bank of Ukraine has ample reserves, one should expect significant economic difficulties for Ukraine in the nearest future. What can policymakers do to sail through this storm?

Figure 1. Commodity prices and capital flows for emerging economies

Source: Federal Reserve Board

Obviously, this is a huge problem that requires much analysis. With the risk of omitting important considerations and oversimplifying the complexity of the required response, this post builds on this call for action and outlines a strategy for what could be done.

The crisis has several components. First, there is a panic in the foreign exchange market (the hryvnia depreciated significantly in the last few days). Second, external demand for Ukrainian goods is collapsing. Third, negative demand spillovers from declining exports. Fourth, the corona virus will likely disrupt production directly and so it will likely look like a negative productivity shock. We have a relatively standard playbook to address the first three components and the fourth one requires more creative responses.

Panic in FOREX markets: During panics, investors liquidate their risky positions in countries like Ukraine to move their funds to safe havens such as U.S. government debt. As a result, many countries experience depreciation of their currencies against the U.S. dollar. This creates several problems and a few opportunities.

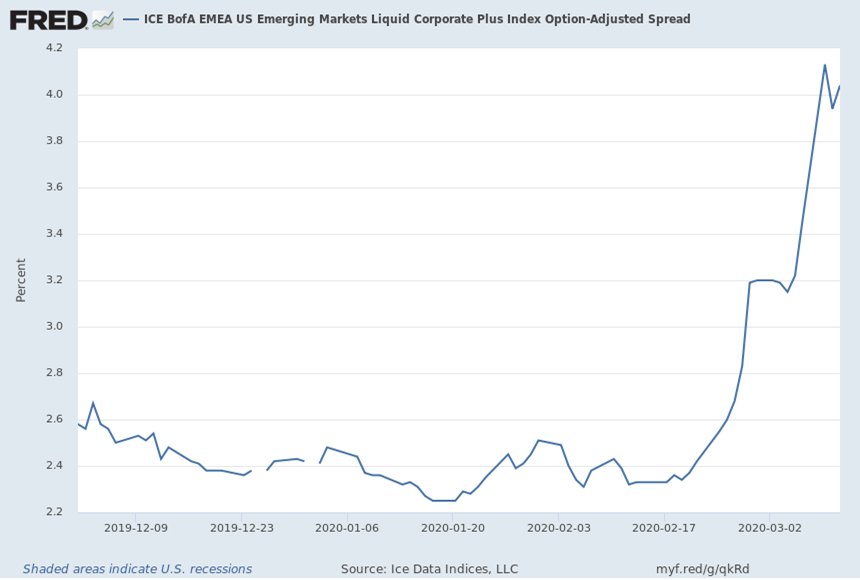

First, this is the time when private businesses and governments have hard time attracting funds in the global financial markets: interest rates increase and access declines. Figure 2 shows that the cost of credit significantly increased for emerging economies during the Great Recession. In all likelihood, Ukraine will have to go through a credit crunch similar in magnitude. Indeed, Figure 3 shows that something similar to the Great Recession is already happening for Ukraine and comparable countries: the spread between interest rates on corporate debt in emerging economies and the interest rate on short-term U.S.government debt is rapidly increasing. It is safe to assume that the IMF and other (semi) government institutions such as the World Bank, European Commission etc. will be the only affordable sources of foreign currency. Setting up an IMF program to secure funding from the IMF and thus also unlock resources from other sources must be a top priority.

Figure 2. Cost of credit and capital flows for emerging economies

Source: Federal Reserve Board

Figure 3. Interest rate on corporate loans for emerging economies relative to the interest rate on short-term U.S. government debt

Source: FRED

Second, large fluctuations in the value of the hryvnia may be disruptive for the economy directly. The banking sector could be under a lot of stress when people panic and rush to withdraw deposits. The NBU must provide abundant liquidity to banks to ensure that the banking sector operates smoothly. Given that banks are now in much better shape than ever before, the concerns about insolvency should be mitigated and hence the central bank should decisively exercise its role as the lender of last resort. It should not relax prudential requirements though.

Third, because inflation expectations are so tied to the exchange rate in Ukraine, a large depreciation of the hryvnia can generate high inflation expectations and hence inflation. This means that the central bank may be forced to raise interest rates to reduce inflation at the cost of exacerbating economic contraction. To avoid this scenario, the central bank should use its reserves to smooth fluctuations in the exchange rate. This is what the NBU has been doing in the last few days but it should be prepared to spend more reserves on this. Note that interest rates are collapsing in advanced economies and so Ukraine can remain relatively attractive for foreign investors even with lower interest rates, which means that the NBU may not have to raise interest rates that much (if at all) to defend the hryvnia. In short, the exchange rate should be determined by market forces in the longer run but the central bank should play a key role in the FOREX market now when the markets are disrupted and the public panics.

Fourth, capital controls proved to be an effective short-run tool to suppress currency and banking runs. And the NBU used this tool in the 2014-2015 crisis. The NBU should consider (and prepare for) using capital controls to tame the panic.

Collapse of exports: As the external demand for Ukrainian exports declines, some depreciation of the hryvnia is inevitable to absorb this negative shock. After all, this is the point of using a floating exchange rate regime. This is the first line of defense.

Given that Ukraine has very limited capacity to absorb steel, chemicals, foodstuffs and other goods produced for foreign markets, there is little the government can achieve by directly buying output of export-oriented industries. However, the government can support these industries indirectly by providing tax breaks, loans, and other forms of short-term assistance to help these industries weather the crisis. Of course, this support should be very transparent and based on the clear and conclusive criteria.

Domestic recession: The government can offset some of the negative spillovers from the reduced employment in export-oriented industries. Specifically, when the economy is in a recession, fiscal stimulus can go a long way in reducing the economic contraction. The worst the government can do now is to try to balance its fiscal position. The experience of Greece during the recent crisis shows that fiscal austerity (raising taxes, lowering spending) is counter-productive. Instead, the government has to implement an aggressive expansionary fiscal policy: more government purchases, more transfers and tax cuts to households and businesses. To pay for the stimulus, the Ukrainian government can unlock additional funding by securing an IMF program: the EU for macrofinancial support, World Bank loans for infrastructure projects, etc. are all conditional on having a program with the IMF. This not only underscores (again) the importance of having a deal with the IMF to get more resources, but also the fact that it is pointless to default on the debt now when Ukraine needs to borrow to pay for the fiscal stimulus (who would lend money to Ukraine if Ukraine defaults?).

Because the government will have limited resources for the stimulus, the response has to be fast (to arrest the crisis before it takes over the economy) and targeted (to utilize precious resources most effectively). To this end, the government can use existing infrastructure (such as the current system of energy/utility subsidies) to distribute resources to those who need help the most: low-income families, the unemployed, and the sick. Injection of cash to these vulnerable groups can not only mitigate the crisis via stimulated consumer spending but also allow these groups to prepare for the worst stages of the crisis.

Supply shock: The corona virus disrupts production in many ways ranging from reduced labor supply (e.g., workers get sick or have to take care of children who are out of school) to shortages of input inventories. The experience of the 1970s when oil prices increased dramatically teaches us that there is no simple solution to this type of shock. However, that crisis also teaches us that there are opportunities: the U.S. oil/gas industry boomed in response to high energy prices. For example, given that Ukraine badly needs investment in its healthcare system, the government can kill two birds with one stone. By spending on healthcare heavily (e.g., hire short-term healthcare workers to attend to the sick, accelerate testing, make coronavirus tests free for the public), the government reduces the consequences of the adverse supply-side shock and provides fiscal stimulus.

In conclusion, we have very hard times ahead but we should not despair. The lessons of the Great Recession and other crises teach us that we can avert the worst. The Ukrainian government should not reinvent the wheel but use these lessons to develop a fast, decisive response to the crisis. This is the time to act!

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations