Such large-scale population movements have a significant impact on the Ukrainian economy, bringing both benefits and costs. In particular, remittances improve the welfare of migrants’ families and stimulate domestic demand; their stable inflow plays a counter-cyclical role in the current economic crisis and is one of the major sources of foreign exchange earnings for the country. On the other hand, emigration reduces the labour supply on the Ukrainian labour market and hence potential output and, if used below their potential at their destination country, leads also to skills waste. Policies to harness the positive effects of labour emigration and to minimise its drawbacks are therefore very relevant for Ukraine. Such policies could focus on the areas of employment, social and tax policies and improving the business environment.

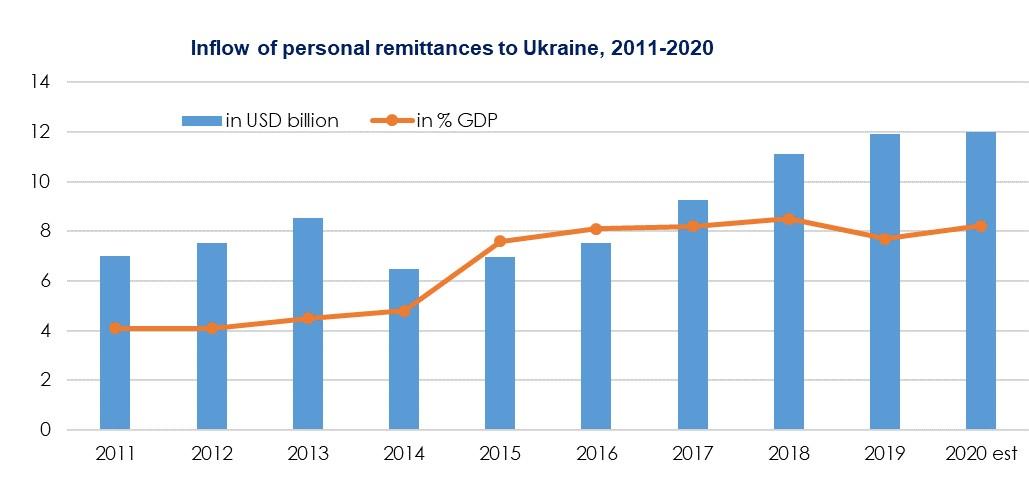

The inflow of remittances to Ukraine is substantial. It has gradually increased from 2015 and reached USD 11.9 billion in 2019, an equivalent of 7.7% of GDP (NBU data). Preliminary data for 2020 indicate that in spite of the economic crisis caused by the pandemic, the inflow of remittances to Ukraine has slightly increased to USD 12.1 billion (figure 1). The stability of remittance flows, in spite of the economic crisis in the countries in which Ukrainian migrants work, can be explained by migrants’ wish to compensate the households to whom they send remittances for having left them behind (the literature describes these as ‘compensatory remittances’). They even tend to increase their remittances when their countries of origin go through difficult economic conditions, to compensate for income shortfalls.

Figure 1.

Source: Data from the National Bank of Ukraine; own estimations

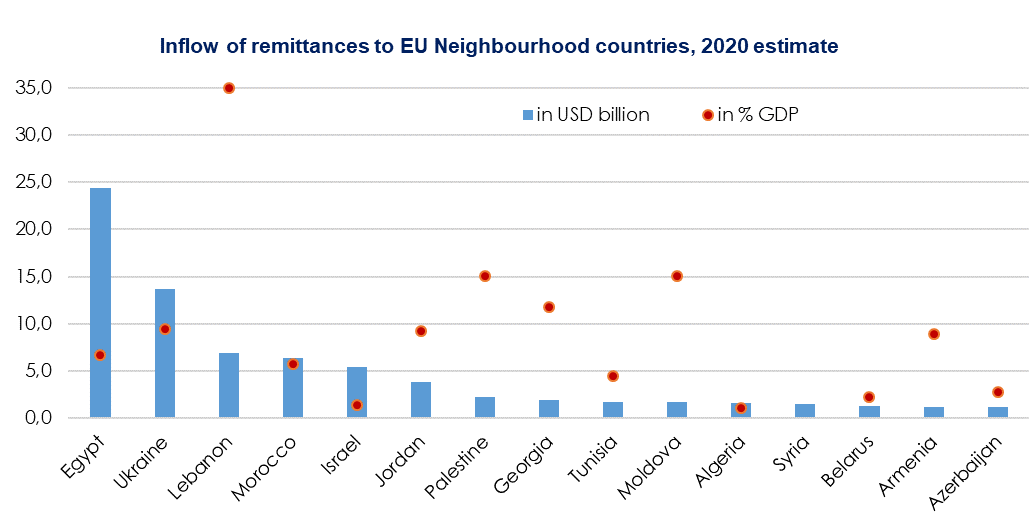

Looking from an international perspective, Ukraine is the tenth-largest recipient of remittances in absolute terms among low- and middle-income countries, and second, after Egypt, among the EU neighbourhood countries (World Bank October 2020 data). Measured as a proportion of GDP, remittances in Ukraine is similar to countries like Armenia and Jordan but significantly lower than in Lebanon, Moldova and Palestine (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Source: The World Bank. There are some differences between the amount of personal remittances estimated by the World Bank and the NBU data

The most evident economic impact of the inflow of remittances is its contribution to improving significantly the welfare of migrants’ families. Remittances are estimated to increase the domestic income of households by around 12%.

Surveys such as IOM (2016) show that around half of the remittances to Ukraine are spent on consumption, while another half are allocated for saving, purchase and renovation of real estate and a small amount for investment. Ukrainian households spend usually around two-thirds of their consumption expenditure on domestic goods and services, which directly stimulates domestic production. Assuming that the same proportion applies to remittances-induced spending, this would mean that the consumption demand from remittances directly pushes GDP up by some 3%. And this estimate does not include the multiplier effect of consumption nor the impact of private investment funded from remittances. Therefore, remittances play an important counter-cyclical role in the current economic crisis in Ukraine.

The impact of remittances and emigration on Ukraine’s public finance is mixed: remittance inflows lead to increased VAT, excise and customs revenues from goods and services paid from remittances. On the other hand, emigrants do not pay labour taxes nor social security contributions in Ukraine, whereas their education entailed a public expenditure. In the current situation, with the whole world experiencing a shock of the same origin, it may be difficult to assess the net impact on public finances in an intertemporal manner. However, over the past years, when Ukraine has experienced significant country-specific difficulties, it is clear that the remittances made an important countercyclical contribution via their impact on especially consumption-induced revenues.

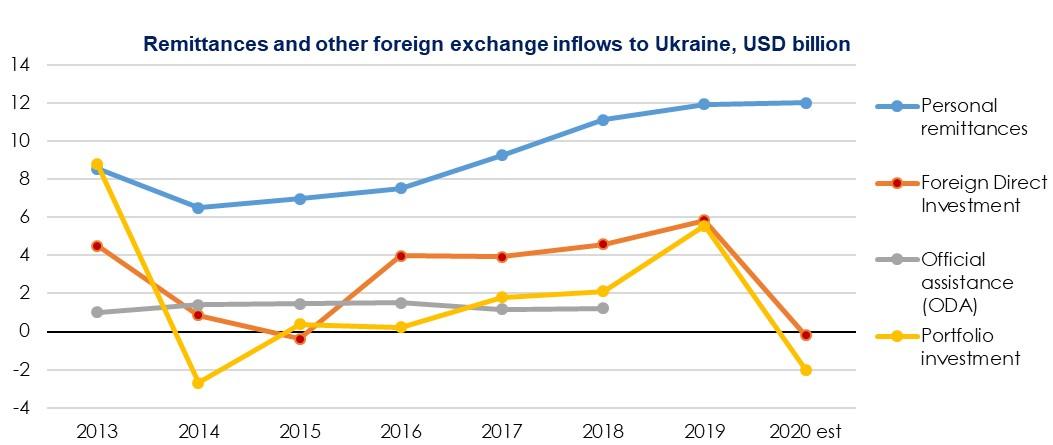

Remittances are one of the largest sources of foreign exchange earnings in Ukraine. The average inflow of remittances into Ukraine since 2011 was more than twice higher than the inflow of foreign direct investment, more than four times the inflow of portfolio capital, and over eight times higher than the inflow of official development assistance. Moreover, while the inflows of FDI and portfolio investment were highly volatile and decreased dramatically in 2014-2015 and more recently in 2020 following the corona crisis, remittances have remained remarkably stable (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Source: Data from the National Bank of Ukraine; own estimations

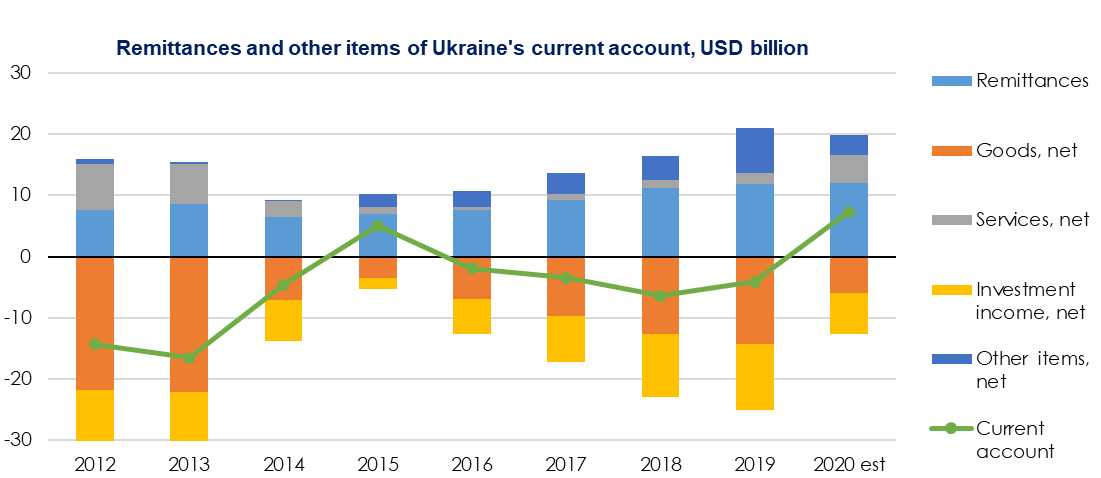

Although the inflow of remittances contributes to a certain extent to a competitiveness-reducing real exchange rate appreciation in Ukraine, the increasing inflow of remittances has, overall, a visible and positive impact on Ukraine’s current account and is the most important item counterbalancing trade and investment income deficits. It has contributed to a more sustainable balance of payments position of Ukraine in recent years, along with other factors including fiscal adjustment, prudent monetary policy, structural reforms, as well as the important official macro-financial assistance and other financial support provided to this country, including by the EU.

Figure 4

Source: Data from the National Bank of Ukraine; own estimations.

The labour migration of between 2 and 3 million individuals has at the same time contributed to reducing the supply of labour in Ukraine causing labour shortages in certain professions. It is also one of the factors (although not necessarily the main one) pushing up wage growth for workers who stay in the country; salaries in Ukraine increased on average by 13% a year in real terms between 2016 and 2019. However, due to the relatively low share of highly-educated workers among Ukraine’s emigrants (16% of migrants had a complete higher education according to SSSU 2017 survey, as against 32% of the employed in Ukraine according to the labour force study – SSSU 2020), a brain drain does not seem to be a particularly relevant issue in Ukraine (and, hence, the impact on productivity should not be exaggerated). An issue of greater concern is skills waste, as most of the Ukrainians abroad are working outside their qualifications or in simple jobs.

One frequently asked question is whether Ukrainian labour migration will continue in its current form. Although wages in Ukraine are rising fast in real terms, salary differences with the main emigration destinations in the EU are so high that they are likely to continue to motivate individuals to work and earn abroad. Moreover, the existence of a large and growing Ukrainian diaspora tends to encourage the migration of other members of the family and friends, by providing information and logistical support in the countries of destination (network effect). At the same time, the destination countries for a part of the emigrants may change, particularly due to the gradual opening of the German labour market for Ukrainian employees. However, linguistic and geographical proximity will continue to weigh in favour of countries like Poland, Czechia and Russia.

In view of the impacts of labour emigration from Ukraine described in this paper, the question of how Ukraine could adjust its policies to improve the benefits and limit the costs associated with its large outflow of workers is particularly pertinent.

Studies on labour migration underline the benefits of engaging with the diaspora and encouraging migrants, especially skilled ones, to invest in, and return to, their home countries. The benefits include bringing back skills, diffusion of technological and managerial knowledge, and the emergence of modern SMEs. Returnees can also bring with them substantial savings: according to the IOM (2016) survey, the volume of annual savings accumulated by an average Ukrainian long-term migrant abroad is more than twice as high as the annual volume of remittances sent by this person. Some countries have managed to attract return emigrants and involve the diaspora in the development of high technology sectors (India, Israel). The Moldovan PARE 1+1 programme, supported by the EU, subsidised the setting up of new SMEs by emigrants returning to Moldova. On the other hand, encouraging migrants to return may diminish the amount of remittances and benefits related to them; therefore, a balance needs to be struck.

Apart from special programmes for returnees, creating a more attractive business environment would clearly be beneficial both for encouraging migrants to return and for stimulating investment in the economy at large. In Ukraine, this requires more effective government institutions, strengthened anti-corruption efforts, reforms of courts and the land market, as well as improved infrastructure.

It is also important to make better use of the workforce remaining in the country. The employment rate in Ukraine is below its EU neighbours like Poland, Romania or Slovakia. Employment policy should seek to improve employability, in particular through reducing mismatches between supply and demand for labour and the reduction of employment in the informal sector.

Another possibility to explore could be a financial mechanism for directing remittances and migrants’ savings towards productive investments in Ukraine. Such instruments have been developed in some countries, such as the ‘diaspora bonds’ issued since the 1950s by the Development Corporation for Israel and sold among the diaspora to finance infrastructure.

It is also important to improve social aspects of Ukrainian migration. Almost 30% of Ukrainian emigrants do not have any legal status (such as residence status or work permit) in their host country, and only 22% of Ukrainian emigrants are covered by social security in the countries where they work (SSSU 2017). Ukrainian authorities could provide more support to migrants, such as advice on legal and administrative issues in the countries where they work and back at home (Luecke and Saha 2019). They could also cooperate with the main destination countries to improve the legal status of labour migrants and increase their social security coverage.

The European Union helps Ukraine cope with many of these challenges. The EU decision to exempt Ukrainian citizens from visa requirement for short stays since June 2017 has improved mobility between the EU and Ukraine, although the rights of Ukrainians to work in the EU are regulated by the national rules of Member States. EU-funded programmes support, for instance, the modernisation of the vocational education system in Ukraine, which is crucial for providing quality skills for the local labour market. The EU also supports improvements to the business environment, which plays a key role for potential returnees and for domestic entrepreneurs (anti-corruption, SME support, tax and customs reform etc.) – both through sectoral grants and as conditions in EU macro-financial assistance programmes.

Disclaimer: This is a shortened and updated version of a paper published under the author’s name as ECFIN Discussion Paper 123, April 2020, copyright of which is with the European Commission. Reuse permitted under the CC BY 4.0 licence. The author expresses his personal opinion, not engaging the position of the European Commission.

Selected references

Chami, R., A. Barajas, T. Cosimano, C. Fullenkamp, M. Gapen and P. Montiel (2008), Macroeconomic Consequences of Remittances, International Monetary Fund, Occasional paper 259, Washington, D.C.

International Monetary Fund (2016), Emigration and Its Economic Impact on Eastern Europe, IMF Staff Discussion Note 16/07.

International Organisation for Migration (IOM 2016), Migration as an Enabler of Development in Ukraine. A study on the nexus between development and migration-related financial flows to Ukraine. Kyiv, http://www.iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_migration_as_an_enabler_of_development_in_ukraine.pdf.

Kapur, D. and J. McHale (2012), Economic Effects of Emigration on Sending Countries, Oxford Handbook of the Politics of International Migration, pp. 131-147, DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195337228.013.0006.

Luecke, M. and D. Saha (2019), Labour migration from Ukraine: Changing destinations, growing macroeconomic impact, German Advisory Group, Policy Studies PS/02/2019, https://www.beratergruppe-ukraine.de/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/GAG_UKR_PS_02_2019_en.pdf.

National Bank of Poland (2018), Obywatele Ukrainy pracujący w Polsce – raport z badania, https://www.nbp.pl/aktualnosci/wiadomosci_2018/obywatele-Ukrainy-pracujacy-w-Polsce-raport.pdf.

National Bank of Ukraine (2018), Personal Remittances Data – Revision for 2015-2017, Statistics and Reporting Department, https://bank.gov.ua/doccatalog/document?id=66364154.

Pienkowski, J. (2020), The impact of Labour Migration on the Ukrainian Economy, European Commission, DG ECFIN, European Economy, Discussion Paper 123, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/dp123_en.pdf

State Statistics Service of Ukraine (SSSU 2017), Зовнішня Трудова Міграція Населення (за результатами модульного вибіркового обстеження), Kyiv, http://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/publ11_u.htm.

State Statistics of Ukraine (SSSU 2020), Labour force of Ukraine 2019: Statistical publication, Kyiv, https://ukrstat.org/en/druk/publicat/kat_e/2020/08/Zb_rs_e_2019.pdf

Temprano Arroyo, H. (2019), Using EU Aid to Address the Root Causes of Migration and Refugee Flows, Florence: European University Institute, https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/61108.