In January 2023, Parliament adopted in the first reading the draft law on adult education submitted by the Cabinet of Ministers, within the framework of implementation of the Association Agreement with the EU (Articles 433, 435). Given the magnitude of destruction caused by the war and the number of refugees and internally displaced persons, it is clear that the Ukrainian labor market will be significantly restructured, making large-scale adult (re)training programs a necessity. Does the draft law address the challenges of the moment?

According to various estimates, a quarter to a third of Ukrainians remain unemployed. This is a lot, given that about 8 million people have left the country. The unemployed have (at least partially) lost their income and have to reduce their consumption which implies that the aggregate demand for goods and services declines. At the same time, it is increasingly hard for businesses to find employees with relevant qualifications. This labor market mismatch existed even before the full-scale invasion, but now it is much larger. Therefore, acquiring new skills or enhancing employee qualifications is critically important for the Ukrainian labor market both today and in the future. The draft law we are examining aims to resolve this issue.

The draft law lays out the adult education framework, its organizing principles, and the rights and responsibilities of various stakeholders. The law introduces several significant changes to the current legislation.

First, it will be possible to recognize non-formal education within the formal education system and obtain full education qualifications based on its results (previously, only professional or partial qualifications could be obtained this way).

Education providers will be able to independently define the form (seminars, courses, training workshops, internships, etc.) and the content of informal education based on professional standards (if available), qualifications characteristics, employers’ tasks, and the needs of the economy and society. However, non-formal education providers must provide complete information about their courses’ content, duration (or the number of ECTS credits), and expected learning outcomes. In this way, the authors of the law create the foundation for a transparent and free informal education market, which is definitely a plus because today labor market needs change very fast.

Secondly, the set of adult education components is changing:

Previously:

|

Now:

|

*According to Mykyta Andreev, the CEO of the Ukrainian Adult Education Association, the clauses on formative education will be excluded from this law during the second reading. Regulation of formative education will be included into the laws on higher education and vocational training.

Additional personally oriented education means enhancing professional qualifications or acquiring new ones, as well as post-graduate studies (however, the latter is mandatory for some professions). According to Mykyta Andreev, personally oriented education is usually informal and is obtained in private institutions. Civic education is about responsible citizenship, including critical thinking and media literacy. Compensatory education is intended for those who did not receive a general secondary education for some reason. Formative education is the so-called “second diploma,” i.e., the acquisition of vocational or higher education (often in a different specialty) by those who already have a diploma from a vocational, technical, or higher education institution. Formative education is usually obtained in state institutions.

A person who was formally employed for at least seven years will be able to obtain a “second education” financed with subsidized loans. Previously, obtaining a “second diploma” was possible only on a fee-paid basis. However, in September 2022, amendments the law on the employment of the population was amended, allowing some categories of people to receive a voucher from the state for obtaining a second vocational or higher education in defined specialties: those over 45 years old, veterans or individuals demobilized from military service (except conscripts), IDPs, persons with disabilities and those who suffered from Russian aggression (previously, vouchers were available only for vocational training). The listed categories of people must take a general educational competence test during admission (similar to the EIT, to be developed by the Ministry of Education and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers). Those enrolling in a bachelor’s or master’s program will take exams directly at higher education institutions.

Third, the role of local authorities in adult education is increasing. In particular, local authorities will be able to establish adult education centers (some communities have already done this) and provide out-of-school education for people over 14 years old. Based on labor market needs assessment, authorities on the ground are expected to create, finance, evaluate, and (if necessary) close such centers. They must also implement regional adult education programs (according to the Verkhovna Rada Scientific and Expert Department, the latter lies within the authority of local administrations). However, any legal entity and private enterprise can offer adult education services. Some Ukrainian higher education institutions already have departments or branches teaching adults. So it seems there will be two main types of “players” in the adult education market: higher and vocational education institutions and local authorities. There will also be room for others, e.g. online course providers.

State-funded institutions or adult education programs will have to undergo quality control organized by the National Education Quality Agency (control will be carried out by the agency or organizations accredited by ut). Institutions offering advanced training for employees for whom it is legally mandatory (e.g., doctors) will need to obtain a license, while accreditation for adult education institutions will be voluntary.

Finally, the draft law suggests introducing a register of personal electronic portfolios in addition to other educational registers. Judging by the description, it will be similar to LinkedIn for professionals subject to additional regulation (in particular, doctors and teachers must get advanced training on a regular basis. After recent reforms, they can independently choose relevant courses or training programs and get points for completing them). Individuals will voluntarily “enter” the register storing their lifetime education records.

The draft law states that the state will fund education for adults with special educational needs and the design and publication in public domain of 100 academic programs and training courses per year (neither the draft law nor the explanatory note says why 100). The use of such courses by entities providing adult education services will be considered as partial state funding of these educational services. Accordingly, information about the educational services providers using these courses will be entered into the Unified State Electronic Database on Education (USEDE) since information about education providers receiving state funding is mandatory entered into the USEDE.

Interestingly, although such initiatives require budget funding (as noted by the Budget Committee), the draft law explanatory note contains the standard phrase that “implementation of the draft law does not require additional financial resources from the state and local budgets.” However, it is clear that the 100 training courses a year are unlikely to be designed on a volunteer basis. Also, opening adult education centers will require funding from local budgets. We hope such spending will be as transparent as possible and implemented with citizen involvement since corruption risks may be there, as with any public expenditure. However, the parliamentary Anti-Corruption Committee thinks there is no such risk. It only proposes to align the draft law provisions regarding licensing with the law on licensing. For some professions, licensing and quality assessment of the training programs and qualifications of teachers are crucial to prevent cases of fake teachers (e.g. a recent “instructor Ali” case).

According to Parliament’s Scientific and Expert Department and Committee on Youth and Sports, one should not consider civic education exclusively in the context of adult education. It is no less important for children (in fact, civic education is also mentioned in the law on education and the law on national and civic identity, and many schools are already teaching the “Civic education” course).

The Committee on European Integration notes that the draft law does not contradict the Association Agreement (according to the AA implementation plan, this law was to be submitted by the end of 2018).

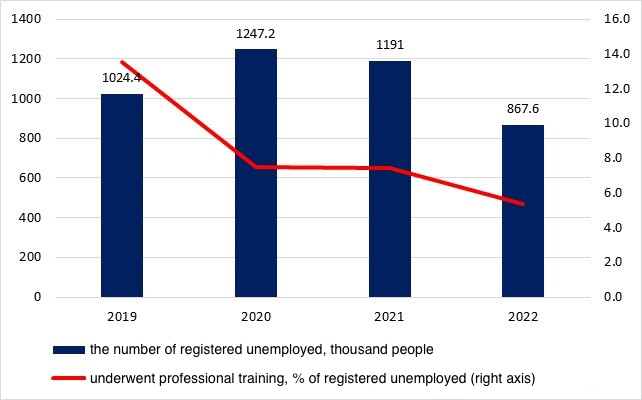

How many people will need retraining or upskilling during the war and after victory? Of course, it isn’t easy to estimate, but we are talking millions, while in pre-pandemic times, the State Employment Service, for example, trained 130-140 thousand people per year (Figure 1). For comparison, online courses offered by Prometheus issued 1.3 million certificates over eight years (i.e., an average of about 162,000 per year).

Figure 1. Training of the unemployed by the State Employment Service

Source: SES

A significant redistribution of labor resources after the war will be a challenge for the state, educational institutions, as well as for employers, and employees. Adoption of this draft law (taking into account the comments of the Scientific and Legal Departments of parliament) will be a necessary first step. However, in the future significant involvement will be required from all the stakeholders.

In particular, educational institutions (with the participation of the Ministry of Education and Science) will have to develop procedures to provide education qualifications based on non-formal education. They will also need to study the labor market to offer sufficiently flexible and relevant adult education courses (competing with a fairly developed private market offering such courses). Employers will need to create new procedures to assess the competencies of their future employees, taking into account the variety of non-formal education options and international experience. On their side, job seekers will need to think about what skills are in demand in the labor market today (and in the future) and find the best ways to acquire those skills: with the help of in-person or online courses, individual consultations, etc.

This article was prepared with the financial support of the European Union. Its content is the sole responsibility of Ilona Sologoub and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations