In March 2014, Forbes estimated that Ukraine had nine billionaires (measured in U.S. dollars). This year, that number has dropped to five. The war has caused social and economic dislocations across Ukraine, making many ordinary Ukrainians poorer than before. It follows naturally that Ukraine’s wealthiest citizens would not be immune to asset loss, even if their plight remains much better than the bulk of their compatriots.

The number of Ukrainian oligarchs whose fortunes have fallen below the nine-digit line is growing. Petro Poroshenko, last year’s seventh wealthiest Ukrainian and the country’s current president, is one of these billionaire-have beens. Poroshenko still owns Roshen, the confectionery company he promised to sell upon taking office last year, but the economic slowdown and conflict with Russia have cut his estimated net worth by some 30 percent. He is now worth a “mere” $720 million.

This article was originally published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

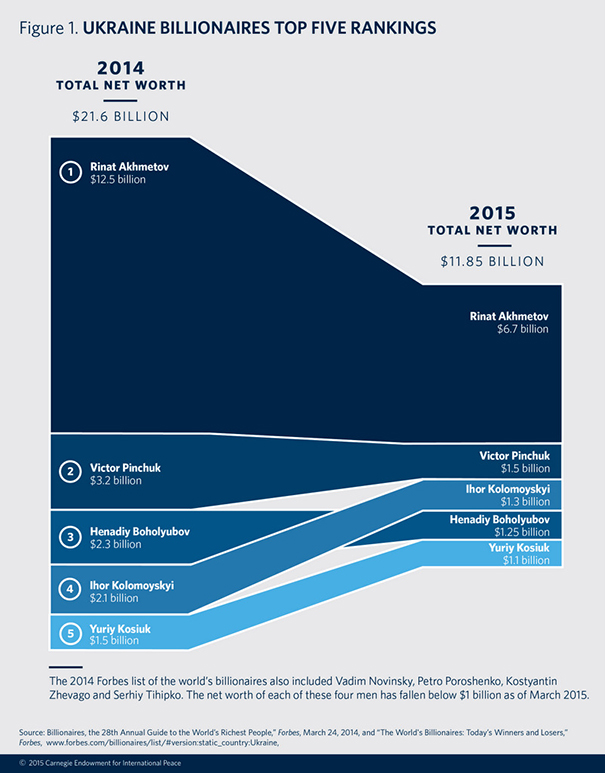

Despite the chaos of last year, the list of Ukraine’s wealthiest citizens—and the distribution of wealth among the top five—remains virtually unchanged. The only notable difference from 2014 is Ihor Kolomoyskyi’s swap in position with his business partner, Henadiy Boholyubov.

Like all Ukrainians, this group of five has been affected by a perfect storm of Russian aggression and economic crisis. But unlike the families fleeing shelling or counting hryvnias to pay for heating, the billionaires are dealing with challenges of a different scale. Many of their assets—like mines, factories, and pipelines—have been destroyed or have fallen into the hands of the Russians (in Crimea) and the separatists (in eastern Ukraine). Trade with Russia, a major market for Ukrainian goods, has been disrupted, while the economic relations with the West have not made up for the shortfall.

Meanwhile, domestic demand has collapsed and the hryvnia has been the world’s worst performing currency this year. Some oligarchs—notably Kolomoyskyi—have used some of their own resources to finance volunteer battalions and build fortifications, although such moves have not been purely altruistic.

Moreover, some of the government’s recent policies have put additional pressure on the country’s wealthiest men. New energy policies—such as lowering electricity tariffs to such an extent that they undermine power stations’ ability to pay for coal—have worked against the interests of Rinat Akhmetov, who has extensive coal mine holdings. A new law deprives gas traders like Dmytro Firtash of free access to the regional gas pipeline system.

The government’s efforts to regain control over the management of state assets used by oligarchs for personal enrichment—namely Ukranafta and Ukratransnafta by Kolomoyskyi —have all taken a toll on the billionaires’ balance sheets.

As a result of these and other factors, Ukraine’s five wealthiest people have lost a collective $9.75 billion in the last year. To put this number in perspective, the IMF’s bailout package is worth $17.5 billion; Ukraine’s total private sector debt stands at about $23 billion.

Akhmetov predictably tops the list of Ukraine’s wealthiest people, although his losses are the largest in absolute terms. Despite becoming 46 percent poorer, he continues to be worth more than the next four Ukrainian billionaires combined. Having previously backed former President Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions, which has now gone into opposition to the government, Akhmetov has quickly tried to diversify his political contacts. Besides the opposition, he reportedly remains on working terms with the separatist leaders in eastern Ukraine, as well as with MPs in President Poroshenko’s party. To this day, Akhmetov controls 75 percent of Ukraine’s thermal power generation market and 99 percent of its electricity exports. He also holds significant stakes in metallurgy, banking, telecommunications, and machinery, making his business empire among the most diversified in the country.

Akhmetov’s story illustrates that despite staggering losses and growing political pressures, Ukraine’s wealthiest people are resilient.

While the upheaval of the last year has not broken up the oligarchic class, there is a good chance that as long as the current government remains in power (and as long as time permits and opportunities present themselves), it will continue chipping away at these informal power structures. The prime minister and the president (despite being an oligarch himself) will no doubt shroud this activity in larger efforts to rebuild state structures that were so weakened under Yanukovych. It remains to be seen whether the gradual dismantling of the current oligarchic system and the re-emergence of a more transparent Ukrainian state will create space for a new generation of business leaders to climb the rankings by crafting their own relationships with the government. The 2016 billionaires ranking may come to surprise us all.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations