On February 21, 2022, Putin publicly laid out his “justification” for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine that was to happen three days later. It included rampant corruption. Putin said that political and state institutions had been changed to benefit certain clans, rather than serving the interests of the people. He talked about oligarchs and financial groups paying off politicians to buy their votes and decisions and that Ukraine was not a democracy.

Authors: Torbjörn Becker, Jonathan Lehne, Tymofiy Mylovanov, Giancarlo Spagnolo, and Nataliia Shapoval

In the West, Ukraine is perceived as a corrupt country. Bill Gates said: “Before the war, the government of Ukraine was one of the worst in the world – corrupt, controlled by a handful of rich people.” Corruption has been a recurrent focus of the IMF, the World Bank and the EU. In 2017, the IMF wrote “The level of corruption in Ukraine is exceptionally high…” and “Regarding the evolution of corruption over time, Ukraine has witnessed no improvement over the last 10 years” (IMF 2017).

These statements are forceful but untrue. Ukraine is a democratic country, the current democratically elected leadership of Ukraine is not controlled by a “handful of rich people”; Ukrainian institutions are functioning and have passed the test of war; and Ukrainian civil society is vibrant and politically powerful. Ukrainians are committed to freedom, democracy and the rule of law. The Russian invasion has made this clear to the entire world.

Corruption, however, is a long-standing problem that peaked during the time of Yanukovich, the pro-Russian president who fled to Russia after the Revolution of Dignity in 2014. In response, Russia annexed Crimea and orchestrated a ‘separatist’ war in Eastern Ukraine. Ukraine elected a new president, signed an association agreement with the EU, and started ambitious reforms. There have been setbacks, but impressive structural reforms have been successfully implemented. A comprehensive anti-corruption infrastructure has been established that includes a corruption prevention agency, an anti-corruption investigation bureau, a special corruption prosecutor’s office, and a special anti-corruption court. These institutions are complemented by a strong community of investigative journalists and civil society.

Recently, their work has brought to light a scandal related to the procurement of wartime supplies. In response, President Zelensky fired senior officials and the anti-corruption law enforcement agencies made several high-profile arrests. Ukraine’s deputy defense minister, deputy prosecutor general, deputy ministers of regional development, and the deputy minister of social policy were also asked to resign. International and domestic audiences have praised Zelensky, the anti-corruption law enforcement agencies, and investigative journalists for their work.

Despite meaningful progress on fighting corruption in Ukraine, corruption and the perception of corruption pose significant obstacles for sustaining the Ukrainian economy during the war and for the recovery after the war. Corruption weakens Ukraine’s ability to resist Russia, and any perception of corruption in Ukraine will be used by Russia for propaganda purposes, and to separate it from the EU, weaken international support, and create political polarisation domestically.

Last year Ukraine was granted EU candidate status and the EU expects anti-corruption reforms to continue. These expectations were reiterated at the Ukraine-EU summit in Kyiv. The EU Commission’s (2022) opinion on Ukraine’s membership application states that one step should be to “further strengthen the fight against corruption, in particular at high level…”. Eradicating corruption was also one of the points that donors stressed at the ‘Ukraine Recovery Conference’ in Lugano in July 2022.

There is a risk that the reconstruction of Ukraine could create new opportunities for corruption. It may however, also be the moment where old ways of doing business and cultural equilibria are disrupted and systemic reform becomes easier. For this to happen, the problem and solutions need to be addressed, head on which is done in our chapter on anti-corruption policies in the reconstruction of Ukraine in Gorodnichenko, Sologoub, and Weder di Mauro (2022).

The state of corruption in Ukraine

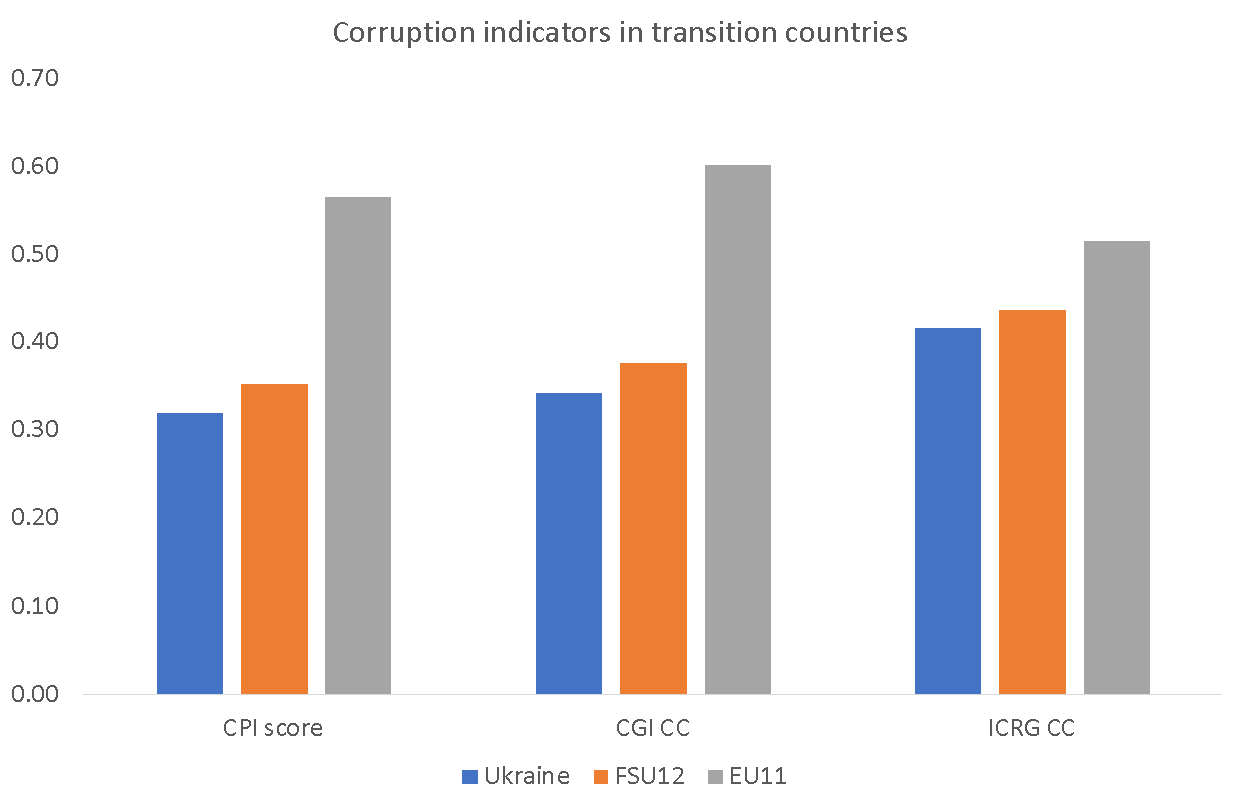

Three decades after the fall of the Soviet Union, there is significant variation in corruption across transition countries (Figure 1). Countries in Eastern and Central Europe that became EU members (EU11) do better in controlling corruption than the twelve countries that came out of the Soviet Union but are not EU members (FSU12) and Ukraine is close to the average FSU12 countries.

Figure 1. Corruption indicators for transition countries

Source: CPI score is from Transparency International, CGI CC is control of corruption from World Bank’s governance indicators, ICRG CC is control of corruption from the PRS group’s International Country Risk Guide.

Note: All variables have been rescaled so 1 is the best score. FSU12 is the average of countries that came out of the Soviet Union and EU11 are transition countries that became members of the EU.

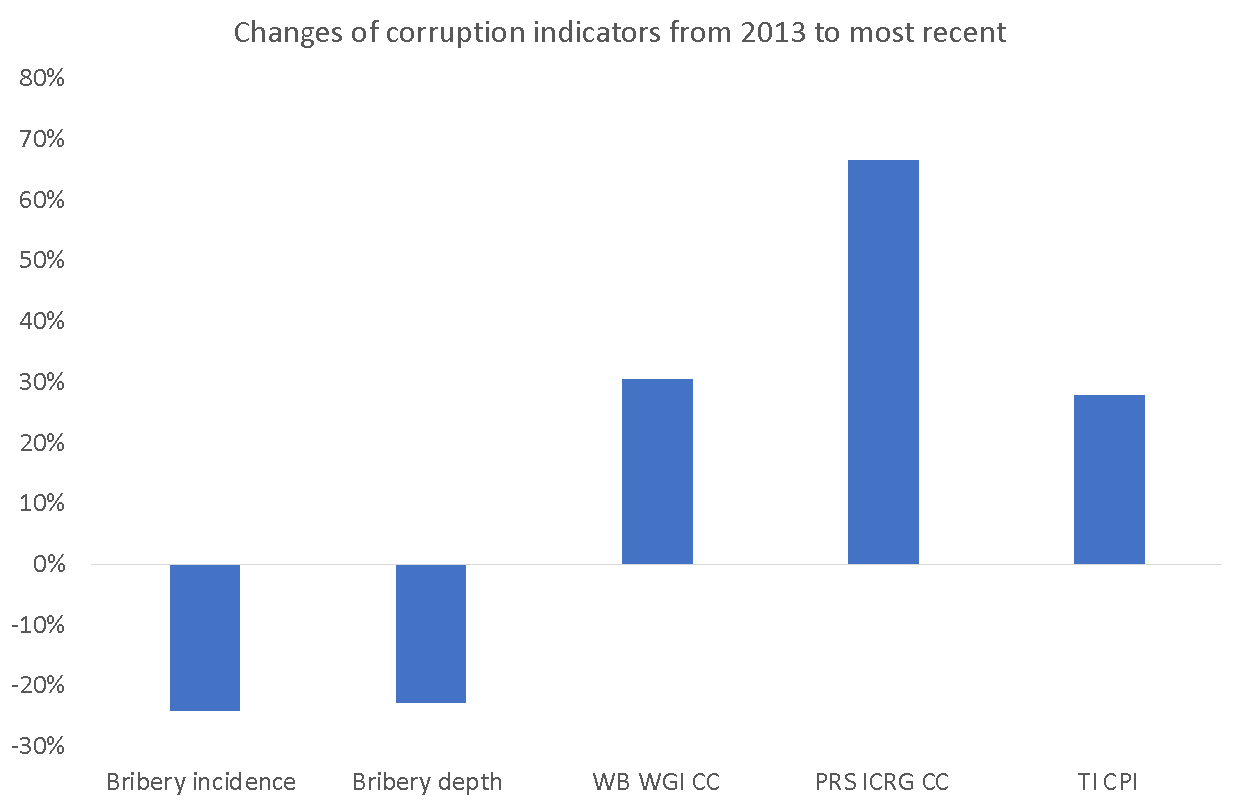

IMF (2017) stated that there had been no progress on limiting corruption in Ukraine for a decade. However, Figure 2 shows that there has been significant progress since the Revolution of Dignity in 2014.

Figure 2. Changes in corruption indicators since the Revolution of Dignity

The improvements are related to reforms in the banking system, procurement, the management of SOEs and the legal system, and new agencies tasked with combating corruption. Ukraine has also digitized government services. During the pandemic, innovative procurement policies in cities like Mariupol and through the central ProZorro platform were praised as examples of best practice in international comparisons (OECD 2020, OCP 2021).

Anti-corruption policies in the reconstruction of Ukraine

The discussion above leads to four principles that should guide anti-corruption policies in the reconstruction of Ukraine:

- Removing opportunities for corruption and rent extraction

- Focusing on monitoring and transparency more than on cumbersome regulation

- Making information and education an integral part of anti-corruption efforts

- Ensuring that anti-corruption and legal institutions are working and trusted

The reconstruction of Ukraine will involve a significant inflow of funds to the country from multiple sources, including legal processes against the aggressor, multilateral institutions, bilateral donors, and private funds. To limit opportunities for corruption in this process, there needs to be a strong coordination between donors and the Ukrainian government in terms of setting priorities, agreeing on conditionality and ensuring transparency and monitoring. This supports the idea of a common, independent agency, as discussed in Becker et al. (2022).

Procurement procedures will also be important to minimize the risk that funds are diverted by domestic or foreign parties. The further development and use of the ProZorro e-procurement platform and open contracting will limit the risk of corruption by maintaining the maximum level of transparency and accountability.

In the aftermath of the war, banks will need support to clean up their balance sheets. This process should be transparent and involve the input of international partners to reduce the risk of inefficiencies and diverted funds. State-owned enterprises need significant reforms to reduce opportunities for corruption and enhance efficiency. These reforms should target how SOEs are run and, over time, include a careful privatization process that can help build financial markets. Other areas of the government and civil service also control significant financial flows and improving the tax system, regulations of markets, and management of public assets will limit opportunities to divert public funds.

It will be important to leverage all parts of society in the process of moving from a high- to a low-corruption equilibrium. Engaging civil society in the reconstruction of Ukraine and ensuring their continued involvement in the agenda on transparency and monitoring should be a priority. Educating students and the wider population on the costs of corruption and how to combat it, will also be important. Whistleblower protection and a culture that rewards individuals who bring wrongdoing to light can contribute to the fight against fraud (Nyreröd and Spagnolo 2021). There will also be a need to support a post-war media landscape that will be part of the discussions on how to use funds for the public good and expose individuals that divert public funds.

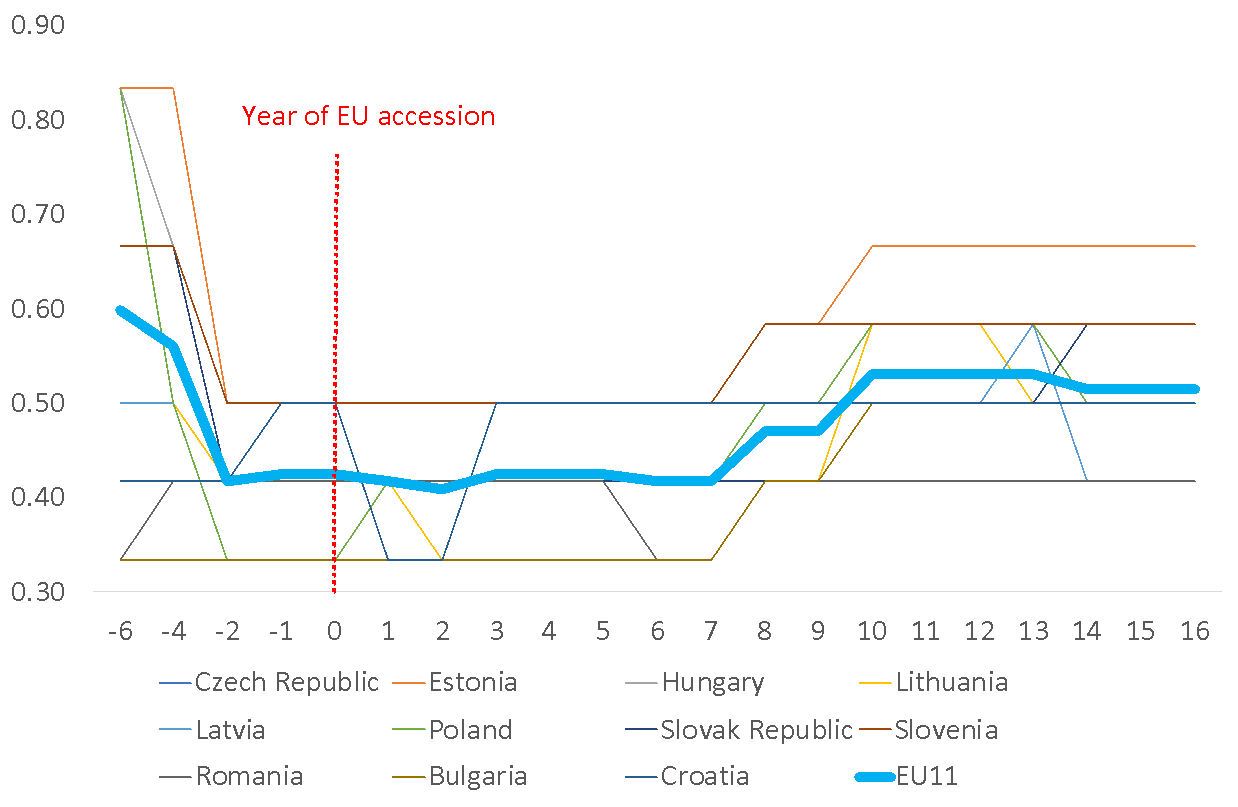

The EU accession process will provide a road map on legal reforms, the functioning of markets and other dimensions that can reduce corruption. However, the accession process alone will not be enough to move Ukraine from one equilibrium to another. Figure 3 shows how corruption indicators have changed for other transition countries that joined the EU. There have been improvements, but the process is slow and there are cases of back-tracking. In short, the accession process will provide an incentive to maintain momentum in anti-corruption reforms but the efforts to move to a low-corruption equilibrium and to stay there, must come from within Ukraine.

Figure 3. Corruption indicators in the EU accession process

Concluding remarks

Anti-corruption reforms need to be at the centre of the reconstruction plans for Ukraine. Not for the sake of donors, but in order to ensure that all funds in the reconstruction process are used for the benefit of all the citizens of Ukraine. This will make more funding available for reconstruction and boost long-term growth. A prosperous Ukraine will be a strong member of the European Union but to get there, ongoing anti-corruption reforms need to be supported and further progress will be required.

References

Bardhan, Pranab (1997), “Corruption and Development: A Review of Issues”, Journal of Economic Literature, September, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 1320- 1346.

Bardhan, Pranab (2012), “Corruption : A Policy Perspective”, mimeo

Becker, T, B Eichengreen, Y Gorodnichenko, S Guriev, S Johnson, T Mylovanov, K Rogoff, and

B Weder di Mauro (2022), A Blueprint for the Reconstruction of Ukraine, CEPR Press.

Becker, T, J Lehne, T Mylovanov, N Shapoval, and G Spagnolo (2022), “Anti-corruption policies in the reconstruction of Ukraine“, in Y Gorodnichenko, I Sologoub, and B Weder di

EU Commission (2022), Commission Opinion on Ukraine’s application for membership of the European Union, Brussels, 17.6.2022, COM(2022) 407 final

Ferraz, C. and Finan, F., 2008. Exposing corrupt politicians: the effects of Brazil’s publicly released audits on electoral outcomes. The Quarterly journal of economics, 123(2), pp.703-745.

Gorodnichenko, Y., I. Sologoub and B. Weder di Mauro (2022), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies, CEPR Press.

IMF (2017), Ukraine Selected Issues, IMF Country Report No. 17/84.

Larreguy, H., Marshall, J. and Snyder Jr, J.M., 2020. Publicising malfeasance: when the local media structure facilitates electoral accountability in Mexico. The Economic Journal, 130(631), pp.2291-2327.

Lugano (2022), Outcome Document of the Ukraine Recovery Conference URC2022 ‘Lugano Declaration’, Lugano, 4–5 July, 2022

Mauro (eds), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and policies, CEPR Press, London. cepr.org/chapters/anti-corruption-policies-reconstruction-ukraine

Mauro, Paulo (1998), “Corruption: Causes, Consequences, and Agenda for Further Research”, IMF Finance & Development, March.

Nyreröd, T and G Spagnolo (2021), “On Corporate Wrongdoing in Europe and Its Enablers”, FREE Policy Brief, 13 April.

OCP – Open Contracting Partnership (2021), How cities can become procurement champions: Guidance inspired by Mariupol, Ukraine.

OECD – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020), “Public Procurement and Infrastructure Governance: Initial policy responses to the Coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis”, OECD Publishing.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations