The co-dependence between coalition and opposition is evident in the numbers. However, these trends do not match with the public announcements of the party leadership. For example, there were no public announcements of the unity between the coalition and opposition in the same way as Poroshenko, Yatsenyuk, and Groisman announced their bonding. And yet, it seems that such announcement would have more empirical ground.

Introduction

On December 15th Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, the Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk and Speaker of the Parliament Volodymyr Groisman announced publicly the declaration of unity. Among other things they condemned confrontations in the Ukrainian Parliament. Ukrainian Parliament has been seen by many as a booster of reforms. Many new faces that had never been in Verkhovna Rada entered it; a large share of MPs were elected by the single-state constituencies, thus having less pressure from the parties; a new coalition was created. However, soon after something went wrong. One of the factions left the coalition, various scandals within factions erupted, not to mention fistfights and verbal assaults in front of the public. Furthemore, previous quantitative studies revealed that MPs tend to co-author legislative acts and vote for them dissent from the faction/coalition lines.

In this blog we provide some new additional quantitative information about co-authorship and co-voting of Ukrainian MPs. This information sheds light on the process of cross-coalition collaboration that has been suspected by many but has been rarely revealed by means of the hard data.

Materials and methods

We use data from the DataVox project for the II session of the VIII convocation of the Ukrainian Parliament. These data include information about the legislative co-authorship and voting by each MP.

Bills initiation

Ukrainian politicians declare their unity and willingness to cooperate. They also declare their loyalty to coalition or opposition (depending on the affiliation). However, little is known about the actual collaboration between them.

A relationship between factions is easily to understand in terms of inflow and outflow.

All members of Petro Poroshenko Bloc (PPB) in total co-authored 7,339 times. They could co-author with anyone – a member of the same faction, a member of another faction from coalition, a member of a faction from opposition. In total 7,339 is the 100% of co-authorship events by Petro Poroshenko Bloc. These 100% are distributed between other factions. For instance, they co-authored 664 times with Opposition Bloc, and 295 times with Batkivshchyna, which is nine per cent and four per cent out of all co-authorship events respectively. We define this as outflow. In other words, MPs from Petro Poroshenko Bloc send 4% of their co-authorship ties to Batkivshchyna (outflow from PPB to Batkivshchyna).

Now let’s look at the same ties from another angle. PPB co-authored 664 times with Opposition Bloc. In total Opposition Bloc generated 1,539 co-authorships. These 664 ties are 43 per cent out of 1,539. In other words, Petro Poroshenko Bloc received 43% of all ties from Opposition Bloc. We call this measure inflow. Dataviz 1 shows inflows and outflows of co-authorship ties.

As one may see, there is a very little variation in terms of out-flow. Almost all of the factions send around 40% of their ties to Petro Poroshenko Bloc and 20% of their ties to NF. Surprisingly, Opposition Bloc sends more ties to PPB than, for example, Samopomich (43% and 35.8% respectively).

Another clear pattern is the lack of reciprocity. Most factions send their ties to PPB and NF, however, the latter factions tend to send very few of their ties back.

Dataviz 1. Inflow/outflow of co-authorship ties

[iframe src=”https://voxukraine.org//dataviz/chrod/chrod.html” width=”100%” height=”690″]

Voting Records

Now we can proceed with actual voting. This time for the simplicity we will focus only on the coalition and opposition instead of looking into factions. We will also present the results for the first and second sessions separately to bring some sense of dynamics.

In roll call vote, an MP chooses whether to respond “yes”, “no”, “do not vote”, “abstain” or be absent from voting on a bill. In our research, we consider only the final voting, i.e. we exclude “first read” voting, voting for amendments and so called “signal voting”. Moreover, we do not discriminate between types of bills such as substantive, procedural, and others. If two MPs vote the same way, we count them as a pair. We tally an agreement when a pair votes “yes/yes”. The result is a weighted, undirected graph of pairwise relationships between MPs. Each pair is classified as either “coalition pair” if they are members of the coalition, or “cross-coalition” if one MP is a coalition member and the other is not.

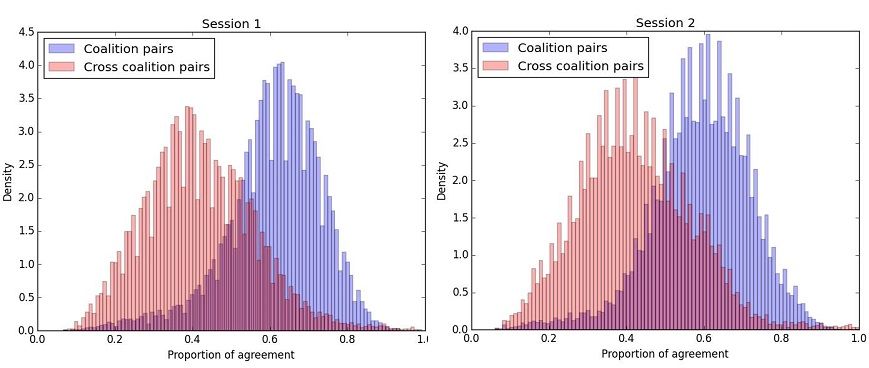

The agreement rates of coalition and cross-coalition pairs are presented in Figure 1. The agreement rates of both pairs are normally distributed, and on average, the coalition pairs achieve higher rates of agreement than cross-coalition pairs. In the second session, the absolute number of votes increased. This yielded an increase in frequency of the cross-coalition agreements. However, the overall distribution of agreements of both type of pairs did not change.

Figure 1. Density of the number of roll call votes agreements between pairs of the coalition pairs and cross-coalition pairs during the 1-st and 2-nd sessions

To shed more light on this we can examine some summary statistics. Table 1 includes information about the total voting by pairs in absolute numbers. For this table we calculated the number of pairs above a passing threshold. To pass a bill, the coalition must collect 226 votes, which is 50% + 1 vote. Thus, the threshold is 50%. In the first session, the number of cross-coalition pairs above the threshold was 9,729. In the second session, this number increased to 10,024. The number of within-coalition pairs was 39,117 in the first session, and then this number fell to 36,867 in the second session.

Therefore, it is possible to see that the capacity of coalition to mobilize MPs weakened in the course of time. In contrast to this, more cross-coalition pairs emerged.

Table 1. Summary statistics of members of the Parliament and voting records

| I session | II session | |

| Dates | 27.11.2014 – 30.01.2015 | 03.02.2015 – 31.08.2015 |

| Coalition MPs | 305 | 305 |

| Non-coalition MPs | 117 | 117 |

| Total votes | 300 | 362 |

| Voting by pairs | ||

| Crosscoalition pairs above the threshold (50%) | 9,729 | 10,024 |

| Within-coalition pairs above the threshold (50%) | 39,117 | 36,867 |

| Average rate of agreement in coalition | 61% | 59% |

| Average rate of agreement in cross-coalition | 42% | 42% |

| Entire network level | ||

| Average Degree distribution | 257 | 248 |

| Density | 0.611 | 0.589 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.885 | 0.872 |

Summary

The main goal of this blog was to give a brief overview of the collaboration between Ukrainian MPs. There are two obvious ways in which MPs can collaborate: they may propose a legislation and they may vote for this legislation. In terms of co-authorship, collaboration between the opposition and coalition was massive. Opposition Bloc sent more ties to PPB than, for example, Samopomich (43% and 35.8% of their ties respectively). In terms of voting, in the course of time more votes were voted by joint efforts of coalition and opposition. The coalition weakened its ability to pass the voting threshold by its own.

In general, the co-dependence between coalition and opposition is evident in the numbers. However, these trends do not match with the public announcements of the party leadership. For example, there were no public announcements of the unity between the coalition and opposition in the same way as Poroshenko, Yatsenyuk, and Groisman announced their bonding. And yet, it seems that such announcement would have more empirical ground.

The discrepancy between the public representation and the party collusions may harm the public’s trust which is a crucial component of legitimacy of Parliament.

Notes

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations