In February 2024, the High-Level Working Group on the Environmental Consequences of War, which includes Ukrainian and European officials, signed an Environmental Compact for Ukraine. The treaty describes post-war environmental restoration in Ukraine (including demining, restoration of the natural environment, and building a green economy). This article explains how to understand the treaty and what changes Ukraine needs to implement it.

What is an Environmental Compact?

The President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy has included the fight against ecocide, environmental security, and environmental protection as the eighth point of his Peace Formula in November 2022. The first security points of the Peace Formula – radiation, nuclear, and food security, which also have a significant environmental dimension, were negotiated in June 2024 at the peace forum in Switzerland with the participation of a hundred countries that share the approaches of the Peace Formula.

Reflecting the environmental priorities of the Peace Formula, in June 2023, the Office of the President of Ukraine established a High-Level Working Group (HLWG) on the Environmental Consequences of War, chaired by Andriy Yermak and Margot Wallström. The HLWG was tasked with scrutinizing the environmental damage caused by the war, assessing how justice can be strengthened, and recommending steps towards green reconstruction and recovery.

The HLWG recognized that many Ukrainian and international experts have contributed to the damage assessment and recovery recommendations, including our recommendations – Towards An Acceptable Accounting of Ukraine’s Post-War Environmental Damages.

In February 2024, the HLWG published an Environmental Compact for Ukraine, providing several recommendations on green recovery and liability for environmental damage caused by the Russian aggression. This Environmental Compact contains only some of the details of green recovery. The HLWG participants have just indicated where they need policy or action, recognizing that the HLWG recommendations should be elaborated in more detail in the implementation phase. To this end, the Ukrainian Government is encouraged to define these details through an active consultation process.

The Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine has launched such consultations by publication of the Action Plan on the implementation of the recommendations set out in the Environmental Compact for Ukraine and organized a roundtable discussion on it.

The action plan includes practical actions to implement the Environmental Compact recommendations by a particular agency or bylaw. The most practically important recommendation is:

“Ukraine should develop a comprehensive strategy for data collection and preservation, based on international best practice.

- This strategy should in particular identify the data and information needed for a possible international compensation mechanism in the future, which could award reparations for well documented damages. Ukraine should ensure that this data is integrated into the Register of Damage caused by the aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, which has been established in The Hague by the Council of Europe”.

However, as we have repeatedly pointed out, in particular in our publications (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), there are deep ideological differences between the “best international” and Ukrainian methods of environmental damage assessment that cannot be overcome at the operational level, i.e., to overcome these differences, the law(s) must be changed. Two years of the author’s work as a member of the Working Group on the development of methods and procedures for calculating damages caused to the environment as a result of Russian aggression established under the Operational Headquarters of the State Environmental Inspectorate of Ukraine (SEI) have shown that the SEI, even with a strong desire, cannot use the “best international” methods of environmental damage assessment, as they fundamentally contradict the current Ukrainian legislation on environmental protection. And the SEI cannot overcome these contradictions on its own.

In our view, the main differences between international and Ukrainian methods of assessing environmental damage from the Russian Federation are:

- Ukraine’s use of methods that, instead of defining damage to the environment, define damage to the state from violating environmental legislation adopted in Soviet times, and

- Ukraine’s application of the Soviet so-called “normative” approach based on the belief that environmental damage occurs only as a result of non-compliance with the standards established by the state and not as a result of exceeding the limits established by nature.

According to the author, these differences will be the main obstacle for Ukraine’s obtaining compensation for environmental damages from the Russian Federation.

The Environmental Compact for Ukraine talks about these ideological differences as well, pointing to such Cross-cutting Themes as Inclusive Policymaking, Countering Corruption and The Concept of Planetary Boundaries, which cannot be addressed by Cabinet of Ministers decrees. Only with the same understanding in Ukraine and the EU of the essence of these Cross-cutting themes can these basic differences be overcome through ideological reforms of environmental policy.

During the transition from the Soviet to the European environmental paradigm, it is very important to avoid misinterpretation of the HLWG recommendations by the Ukrainian society. Therefore, below we explain the cross-cutting themes and priorities of the Environmental Compact for Ukraine, based on the author’s experience gained while working as a member of the SEI Scientific and Expert Council.

A draft Roadmap for Environmental Policy Reforms that bridges the gap between international and Ukrainian environmental damage assessment methodologies, along with samples of necessary legislative changes, was recently proposed by the author within the UNDP “Mitigating the risks of long-term environmental disasters in Ukraine through the establishment of a Coordination Centre on Environmental Damage Assessment” Project.

Cross-cutting theme 1: Inclusive Policymaking

The cross-cutting theme of inclusive policymaking reminds us that the environment is a common resource and therefore needs to be managed inclusively, not extractively.

What is the difference between “inclusive” and “extractive” approaches to environmental governance?

This question is well explored in the book by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson “Why Nations Fail?“. Acemoglu and Robinson explain the decline or prosperity of nations by the presence or absence of “extractive” or “inclusive” institutions. They define the difference between the two as follows:

«Inclusive institutions are those that integrate all stakeholders, i.e., allow participation of a significant share of citizens in economic relations with an opportunity to profit (win-win situation).

Extractive institutions are institutions that have the opposite properties, i.e., they are aimed at extracting income and benefits from one group of people in favour of another one (the so-called zero-sum game)».

What is wrong with extractive institutions in the environmental sector? The thing is that their activities are limited to control and supervision and are a classic “zero-sum game” that divides society into polluters and controllers and does nothing for the environment, unlike the approach of inclusive institutions that integrates all stakeholders for achieving common development goals.

What is the problem with a zero-sum extractive game?

First, the extractive approach measures only compliance with standards. And it is measured dichotomously, i.e. as a binary variable (compliant/non-compliant), without specifying how significant the non-compliance is. This simplistic measurement does not give an idea of the seriousness of the problem and thus makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of environmental policy.

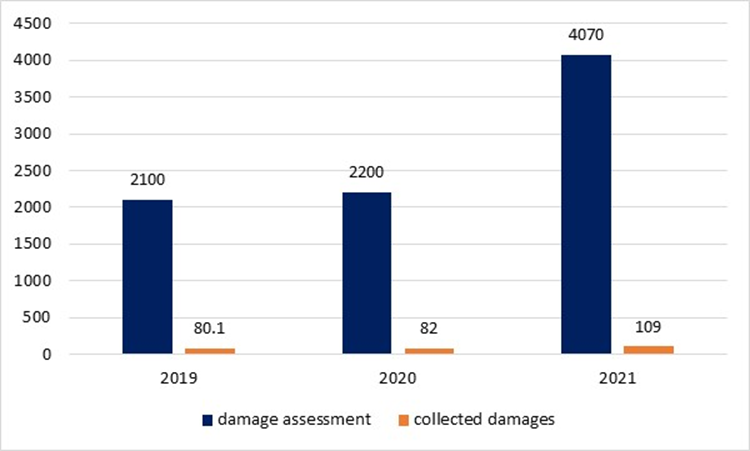

Second, extractive management is a dichotomous “zero-sum game” (i.e., a situation in which there is always someone who has won something and someone who has lost as much) between lawbreakers and inspectors who record these violations. Management based on compliance with norms and standards makes it possible to catch violators but does not allow even to pose the question of where, how and why the environment should be improved. Before the full-scale war, the State Environmental Inspectorate was able to collect from violators of environmental legislation for damages to the state very small amount of funds – about a quarter of the SEI budget (figure 1). This barely affected the behavior of polluters or the improvement of the environment.

Third, the harmful-harmless or security-insecurity dichotomy leads to the concept of “zero risk”, where environmental standards and regulations are set at a level that, at least in theory, poses “zero risk” to human health. Concentrations even slightly above the maximum permissible concentration are considered to pose a potential health risk. This results in a situation where no risk or environmental impact is acceptable. However, if no level of risk is considered acceptable, then no technical or economic priorities can be set. Without risk analysis and assessment, it is impossible to quantify environmental damage and liability for that damage. Consequently, it is impossible to apply cost-benefit analysis and develop effective environmental remediation programs.

From a scientific point of view, the two-tiered regulatory approach also has significant managerial limitations, because you cannot manage what you cannot measure and when you have only two answers: the standards are exceeded or not. This leads to a dichotomous system of determining environmental impact and two-tiered purely administrative liability for violation of norms/standards of environmental impact/pollution since the state does not assume full responsibility for pollution within the established standards. No institution assumes environmental liability for restoring the environment to its natural or at least “good” condition (similar to damage to infrastructure from natural or man-made disasters).

Thus, inclusive policy making means that to improve the effectiveness of the state environmental control system, the Government should move from controlling polluters and other violators of environmental legislation to managing common natural resources for the benefit of the entire society. At the same time, the Ministry of Environment and the SEI should be transformed from “extractive command-and-control” institutions into “inclusive” institutions that integrate all stakeholders in achieving common goals of natural resource management.

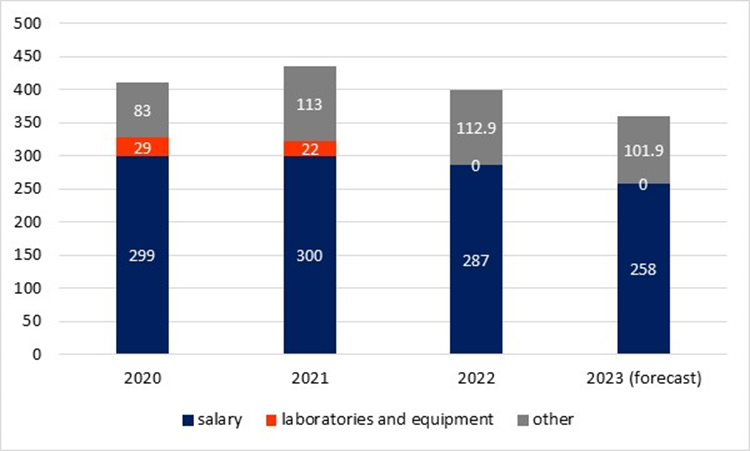

Figure 1. Environmental damage assessed by SEI (a) and SEI funding (b)

Environmental damage, UAH million

SEI funding, UAH million

Data source: official SEI presentation at the SEI Scientific-expert council meeting

Cross-cutting theme 2: Combating corruption

“Gaining the full trust of the Ukrainian people, donors and investors will require a firm commitment to transparency and countering corruption. This will be critical for implementation of current proposals.”

The “normative” approach to environmental damage assessment used by Ukraine retains signs of double standards, i.e. one of the types of “Soviet” corruption, about the undesirability of returning to which the US Secretary of State spoke at the meeting with students of Kyiv Polytechnic University. For example:

- Under the “normative” approach, the amount of environmental damage depends on the polluter. In the “pre-war” 2021 year, the SEI estimated billions of hryvnias, and in 2022 – a thousand times more of damages from emissions and discharges, since the Ministry of Environment included arbitrary military coefficients into the methodology for assessing environmental damage in 2022.

- The “normative” approach assumes that damage occurs only in the case of excessive environmental impact, while “within-limits” impact does not cause damage. For example, emissions from explosions or burning oil products at bombed oil depots are considered environmental damage. While emissions from the combustion of the same fuel at thermal power plants and in Ukrainian cars are not considered damage, since these emissions were authorized. The International Court of Justice will not accept this different approach to Russian and Ukrainian polluters.

- The discharge of 18 km3 of water from the blown-up Kakhovka reservoir is considered damage as an unauthorised water withdrawal. However, the authorised supply from the same reservoir to Crimea is not considered a damage. However, since the water returns to the river, the discharge cannot be considered damage to nature (we are not talking about damage to people and infrastructure from flooding here).

- The European Commission describes the corruption of the Soviet “normative” approach as follows: “There is a striking lack of connection between the objectives of this system of environmental pollution control and its actual results in practice. Indeed, the inability of industry, in particular, to meet the maximum permissible discharge requirements necessary to comply with the permissible discharge concentrations has led to a system of “temporary permits” that set higher discharge limits, often in accordance with actual discharges. These temporary permits, therefore, do not provide any incentives for industry to reduce pollution, and instead of being temporary, they become the norm“.

Cross-cutting theme 3: The concept of Planetary Boundaries

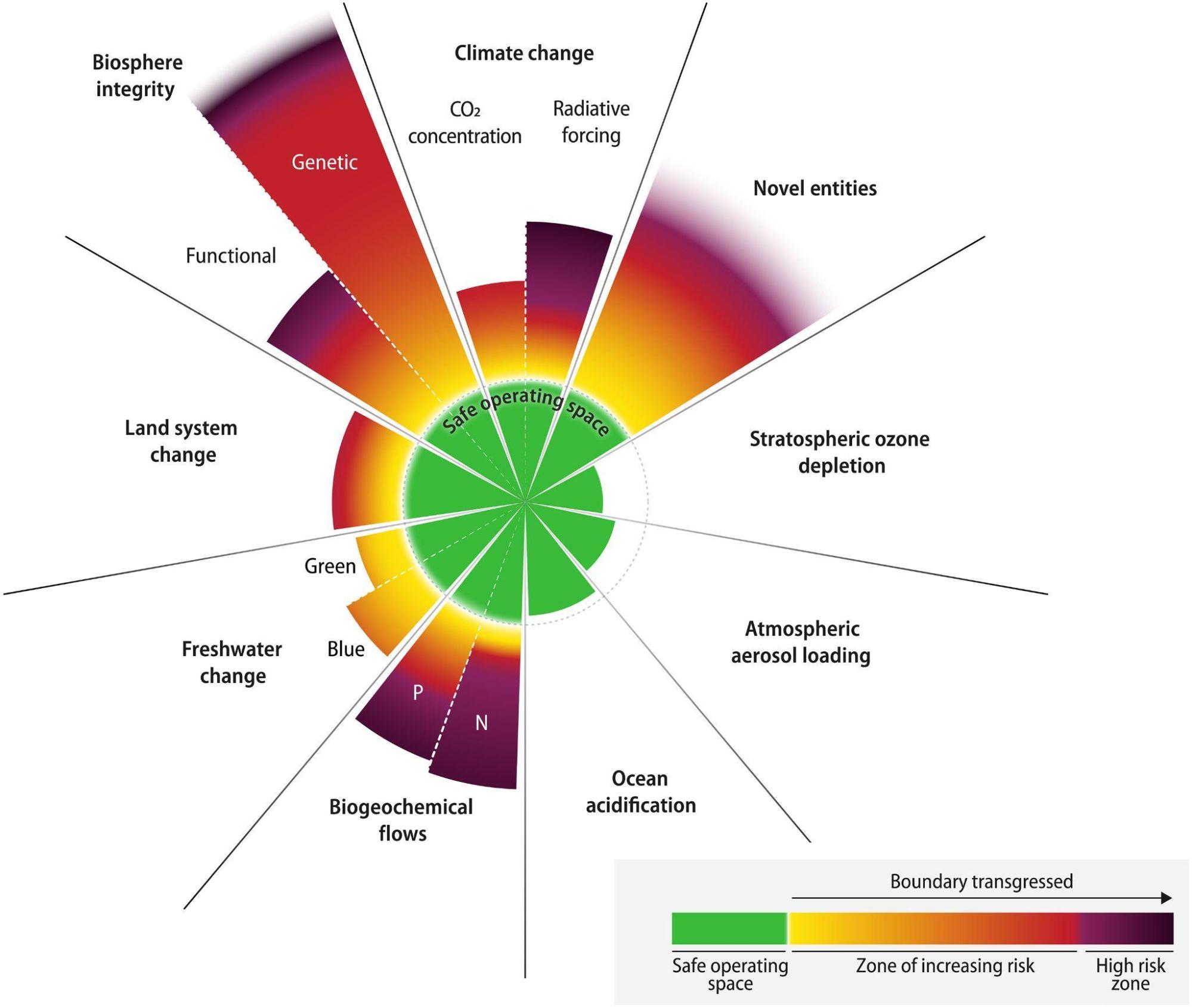

The concept of “Planetary Boundaries” (see Box 1) should help Ukraine in its recovery and reconstruction. This scientific concept shows that global resources are limited and that all countries must work hard to reduce pollution, protect natural areas, and reduce the burden on the environment and climate. This orientation will help Ukrainians see all the interconnected factors involved in environmental restoration and ensure that Ukraine positively contributes to global efforts to address climate and ecosystem health. The Environmental Treaty stipulates that Ukraine must take into account the concept of Planetary Boundaries when rebuilding.

“RECOMMENDATION 35: Working with international partners, Ukraine should undertake a detailed assessment of its position in relation to the planetary boundaries.

- This should include establishing the national boundaries within the nine criteria of this framework; assessing the current national status or performance in relation to each; and identifying specific policy pathways to ensure that Ukraine stays within the safe operating space of the national boundaries.

- In the meantime, while that review is underway, Ukraine should proactively incorporate the lessons and general guidance of the nine planetary boundaries into all of its policymaking related to recovery and reconstruction.

- The international community should provide support for this review and analysis. The EU has already undertaken a planetary boundaries assessment for the Union as a whole, as have several individual member states, and thus the Ukraine-specific analysis should coincide well within Ukraine’s EU accession process and the European Green Deal”.

Box 1: Six of the nine planetary boundaries of the Earth are broken

Six of the nine parameters that define the boundary conditions for the safe existence of humanity have been violated in the Earth’s ecosystem.

Johan Rockström and others, Science Advances, v.9, No.37, 2023.

Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries

Abstract.

This planetary boundaries framework update finds that six of the nine boundaries are transgressed, suggesting that Earth is now well outside of the safe operating space for humanity. Ocean acidification is close to being breached, while aerosol loading regionally exceeds the boundary. Stratospheric ozone levels have slightly recovered. The transgression level has increased for all boundaries earlier identified as overstepped. As primary production drives Earth system biosphere functions, human appropriation of net primary production is proposed as a control variable for functional biosphere integrity. This boundary is also transgressed. Earth system modeling of different levels of the transgression of the climate and land system change boundaries illustrates that these anthropogenic impacts on Earth system must be considered in a systemic context.

Fig. 1. Current status of control variables for all nine planetary boundaries.

Six of the nine boundaries are transgressed. In addition, ocean acidification is approaching its planetary boundary. The green zone is the safe operating space (below the boundary). Yellow to red represents the zone of increasing risk. Purple indicates the high-risk zone where interglacial Earth system conditions are transgressed with high confidence. Values for control variables are normalized so that the origin represents mean Holocene conditions and the planetary boundary (lower end of zone of increasing risk, dotted circle) lies at the same radius for all boundaries (except for the wedges representing green and blue water, see main text). Wedge lengths are scaled logarithmically. The upper edges of the wedges for the novel entities and the genetic diversity component of the biosphere integrity boundaries are blurred either because the upper end of the zone of increasing risk has not yet been quantitatively defined (novel entities) or because the current value is known only with great uncertainty (loss of genetic diversity). Both, however, are well outside of the safe operating space. Transgression of these boundaries reflects unprecedented human disruption of Earth system but is associated with large scientific uncertainties.

We expect that the concept of “Planetary Boundaries” will be difficult to perceive in Ukraine, since many Ukrainian lawyers do not recognize even theoretically the presence of some measurable boundaries established by nature, not the state (e.g, Planetary Boundaries or Limits to Growth).

An excellent example of failure to recognize the existence of limits to resource consumption is the current debate over the restoration of the Kakhovka reservoir. Everyone recognizes that the blowing up of the Kakhovka dam is a classic example of “ecocide” as the mass destruction of flora and fauna. However, almost no one is ready to recognize the creation of the Kakhovka reservoir as an ecocide, even though the total volume of the Dnipro reservoirs is one-third higher than the Dnipro’s flow in a low-water year and, accordingly, exceeds not only the water withdrawal limits according to UN Sustainable Development Goal 6.4.2. but even the Soviet basin water withdrawal limits.

This attitude to the limits of development and resource consumption has existed in Ukraine since the discussion of the Concept of Sustainable Development (SD) after the Rio Summit in 1992. Almost all humanitarian scholars, especially lawyers, perceived the concept of SD as “the right of future generations to have their needs met”. Although the Bruntland’s “Our Common Future” report is not about the “rights“, but about the “ability of future generations to meet their resource needs”.

Thus, Ukrainian decision-makers have narrowed the concept of SD to a purely human rights issue of protecting the social minimum of natural resources, rejecting the problem of establishing an environmental maximum of resource use due to their physical limitations.

And since, unlike opportunities, the right has no limits, this immediately rejected all arguments in favour of setting limits on consumption. As a result:

- the Constitution of Ukraine mentions only the right to a clean environment, but not the clean environment itself,

- environmental impact assessment in Ukraine is only a legal procedure that lacks a measurable quantitative assessment of the impact,

- the Law on environmental control refers to the control of “damages and losses caused to the state as a result of violation of environmental protection legislation” rather than control of measurable environmental damage.

Thus, Ukraine’s recognition of the Planetary Boundaries concept will require a rethinking of the Sustainable Development Concept, which seems to be a difficult task. Numerous UN summits, starting with those in Rio de Janeiro (1992) and Johannesburg (2022), have tried to bring Ukraine back to the universally recognized Brundtland Concept, but so far without any success.

In addition to the cross-cutting themes, the Environmental Compact includes three priorities that will help the Ukrainian government and society rethink the concept of environmental damage and its measurement.

Priority 1: Risk reduction

The words “risk reduction” appeared for the first time in Ukrainian legislation when updating the Environmental Strategy in 2019, in which the Government proposed quite clearly defined and measurable environmental goals – “Ensuring sustainable development of Ukraine’s natural resource potential” and “Reducing environmental risks”. However, understanding this paradigm shift in environmental governance is a constant challenge. Most experts and government officials, even after the Strategy was updated, remained committed to the “normative” approach. They still consider the national environmental goals to be Ensuring environmental security and Compliance with environmental standards/legislation, the achievement of which (and the effectiveness of achievement) cannot be measured.

The transition from compliance to risk mitigation was not realized in society and was not reflected in other laws and regulations. Thus, the Law “On Environmental Protection” still contains “Soviet” dichotomous definitions of environmental security and procedures for environmental impact assessment (EIA). According to the respective EIA Law, EIA is a procedure that does not involve measuring the magnitude of the impact. State construction norms for EIA still define risk as the probability of a negative impact, although ISO defines risk as the effect of uncertainty. And Civil Code defines security as the absence of risks.

Unfortunately, during the second reading, the MPs changed the wording of Goal 4 of the Environmental Strategy, replacing “Reducing environmental risks to a socially acceptable level” by “Reducing environmental risks in order to minimize their impact on ecosystems, socio-economic development and public health.” This change of wording demonstrates that MPs do not understand the nature of environmental risks, the causes of natural threats from the environment and ways to reduce damage from natural hazards.

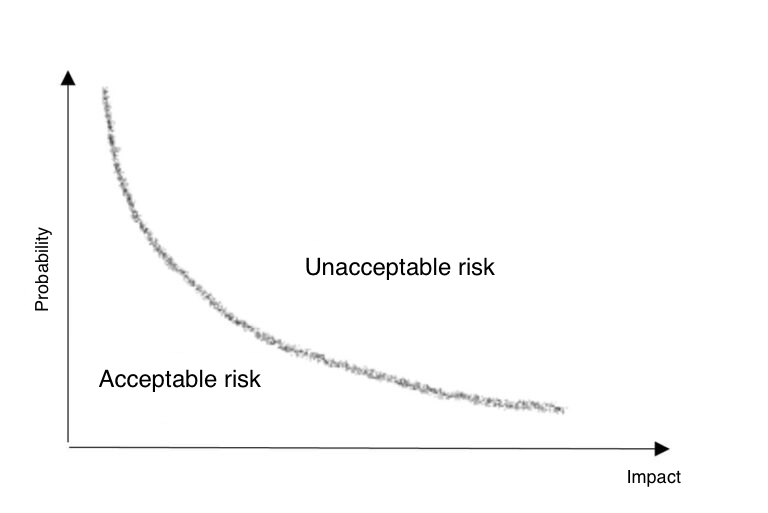

The current understanding of the nature of environmental risk is that:

- It is not the risk itself that affects ecosystems or populations, but the negative event that affects them;

- Risk is the product of probability of a threat and its impact, not just the probability of a negative impact;

- Environmental risk is the probability of adverse consequences for ecosystems as a result of the dynamic interaction between environmental threats and the vulnerability of ecosystems affected by these threats;

- The magnitude or likelihood of a hazard can be reduced by reducing, for example, the emission of pollutants or greenhouse gases;

- The impact of a negative event can be reduced by reducing the vulnerability and exposure of the population and ecosystems to the threat: for example, construction in the area of possible flooding can be prohibited, early warning systems can be installed, and strict construction codes can be implemented in earthquake-prone areas, etc.;

- Acceptable risks are those for which the product of the probability of a negative event and its impact is below a certain limit.

According to the OECD, the risk-based approach defines security by determining acceptable levels of risks in terms of their probability and potential consequences (economic, environmental, social) and balancing possible losses with the expected benefits of improved security. This is a cost-benefit analysis, which should help ensure that the level of risk is consistent with social values and that society’s response is proportional to the magnitude of the risk. The risk-based approach also helps to identify high-risk areas which should be managed right away. The risk-based approach creates additional opportunities for environmental management, since reducing each of the risk multipliers – both the likelihood of a threat and its impact – reduces the risk.

Priority 2: Damage monitoring

“RECOMMENDATION 2: Ukraine should develop a comprehensive strategy for data collection and preservation, based on international best practice.

- This strategy should in particular identify the data and information needed for a possible international compensation mechanism in the future, which could award reparations for well documented damages. Ukraine should ensure that this data is integrated into the Register of Damage Caused by the Aggression of the Russian Federation Against Ukraine, which has been established in The Hague by the Council of Europe”.

The main difference between the Ukrainian and Western approaches to environmental damage assessment is that in Ukraine, “environmental damage” is “damage and losses caused to the state as a result of violations of environmental protection legislation“, while in the EU and the US, “environmental damage” is measurable damage to the environment and measurable losses of ecosystem services.

The creation of the Register of Damages for a possible international compensation mechanism based on the best international practices means, in our opinion, the mandatory definition of damages based on the definitions of:

- the UN Compensation Commission established after the Gulf War and

- Directive 2004/35/CE of the European Parliament and Council of 21 April 2004 on environmental liability with regard to prevention and remedying of environmental damage.

The UN Compensation Commission, when considering claims for environmental damage, relied on the definitions of the US Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act [CERCLA]. The definitions used by CERCLA focus on natural resources and ecosystem services. Thus, the UN Compensation Commission understood:

- damage as an observed or measured negative change in a natural resource or a deterioration in the quality of services related to natural resources,

- compensation for damages as compensation for damage, destruction, loss or inability to use natural resources, including reasonable costs for assessing damages,

- restoration as actions aimed at returning damaged natural resources or services to their baseline condition – the state of natural resources and ecosystem services that would have existed if the incident had not occurred,

- primary restoration as any action, including natural restoration, that returns disturbed natural resources and ecosystem services to their original state,

- compensatory restoration as any action aimed at compensating for the temporary loss of natural resources and ecosystem services that occurs from the moment of the incident to the moment of restoration,

- that measures to restore damaged resources should be aimed at primary restoration, i.e. restoration of ecological functioning,

- that compensatory restoration should be considered only when there is sufficient evidence that primary restoration will not be able to fully compensate for the identified losses, i.e. restore ecological functioning.

American definitions of CERCLA are very close to the definitions of “environmental damage” in the European Directive 2004/35/EC:

“Environmental damage: negative measurable changes in a natural resource or disruption of a natural resource-related service that may occur directly or indirectly”.

Directive 2004/35/EC distinguishes between three types of “net environmental damage”:

- damage to protected biological species and natural habitats, in particular, any damage that significantly affects the establishment or maintenance of a favourable state of conservation of such natural habitats or biological species; the extent of the consequences of such damage shall be assessed relative to the baseline,

- damage affecting water resources, in particular damage that significantly adversely affects the ecological, chemical or morphological status or ecological potential of water resources,

- soil damage, in particular any soil contamination that causes a risk of significant adverse effects on human health from the direct or indirect penetration of substances, preparations, organisms or microorganisms into the surface or soil.

Priority 3: Ensuring accountability (liability)

“In addition to the prosecution of environmental damage, either as a war crime or as ecocide, accountability must also include obtaining reparations, in particular from the State responsible for the damage”.

In the current Ukrainian legislation, the concepts of “environmental liability” and “environmental remediation liability” are absent, there is only accountability for violations of environmental legislation and for “ecocide – mass destruction of flora or fauna, poisoning of the atmosphere or water resources, as well as other actions that may cause an environmental disaster.”

Individual criminal liability for “ecocide” does not provide for any quantifiable material compensation for such environmental damage, either in Ukraine or elsewhere in the world.

In Ukraine, the material liability of a “polluter” is determined through a fine for violation of environmental legislation, which goes to the budget. Paid fines relieve the polluter of responsibility for pollution, but do not transfer environmental liability from the polluter to the state and do not establish the state’s financial responsibility for remediation.

Discussions with Europeans on the topic of the environmental liability of the state took place as early as the Kyiv Conference of Environment Ministers in 2003, which emphasized that without recognizing the state’s liability for past pollution, no investment could be expected. Later, the debate on liability intensified when Ukraine transitioned from the Soviet system of state environmental expertise, which permitted pollution, thus taking responsibility for pollution away from the state to the European system of environmental impact assessment (EIA), which provided only recommendations, leaving responsibility to the polluter. Again, no understanding was reached, as evidenced by an analytical report of the European Commission on Ukraine’s accession to the EU.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In our opinion, the misunderstanding of the essence of the European approach to EIA goes back much further, to the time of Martin Luther with his criticism of the practice of selling indulgences by the papal office and the exclusive rights of the pope to forgive sins. Max Weber in his work The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism believed that Luther’s theses contributed to the spread of capitalism and the establishment of market relations in the economy.

Luther’s reforms initiated the Reformation, which, unfortunately, did not reach Kyiv. Instead, from the “Third Rome” the papal practice of selling indulgences for the sin of pollution in the process of Soviet environmental assessment came to Kyiv. Even after the formal transition in Ukraine from environmental expertise to environmental impact assessment (EIA), EIA remained only a legal “procedure for absolution for the sin of pollution” – compliance with the law – rather than a process of measurable impact assessment to reduce environmental impact. And without measurable environmental impact assessment, we can see neither compensation for environmental damage nor EU membership.

Therefore, in the Roadmap for Environmental Policy Reforms based on the recommendations of the Environmental Compact and to overcome the discrepancies between international and Ukrainian methods of environmental damage assessment, I propose the following changes to the basic environmental laws of Ukraine:

| Current version | Proposed wording |

| The Law of Ukraine “On environmental preservation” | |

| Article 50. Environmental security

Environmental security is a state of the environment, which ensures prevention of deterioration of the environmental situation and the emergence of a danger to human health |

Article 50. Environmental security

Environmental security is the reduction of environmental risks to a socially acceptable level |

| Article 34. Tasks of Control in the Field of Environmental Protection

The objectives of control in the field of environmental protection are to ensure compliance with the requirements of environmental protection legislation by all state agencies, enterprises, institutions and organizations, regardless of ownership and subordination, as well as by citizens. |

Article 34. Tasks of Control in the Field of Environmental Protection

The objectives of control in the field of environmental protection are to ensure efficiency in achieving the goals of the state environmental policy, controlling negative measurable changes in natural resources and natural resource-related services, compliance with the requirements of environmental protection legislation by all state bodies, enterprises, institutions and organizations, regardless of ownership and subordination, as well as by citizens. |

| The Law of Ukraine “On environmental impact assessment” | |

| Article 2. Content and subjects of environmental impact assessment

1. An environmental impact assessment is a procedure that involves: 1) the preparation by an entity of an environmental impact assessment report … |

Article 2. Content and subjects of environmental impact assessment

1. Environmental impact assessment is a process that involves: 1) the preparation by an entity of a measurable environmental impact assessment report … |

| The Law of Ukraine On the strategy for the state environmental policy of Ukraine until 2030 | |

| Objective 4. Reducing environmental risks to minimize their impact on ecosystems, socio-economic development and public health. | Objective 4. Reduce environmental risks to a socially acceptable level. |

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations