Countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) account for a significant share in Ukraine’s foreign trade, and their share has increased considerably since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It is crucial for Ukraine that its trading partners grow sustainably. However, in a high interest rate environment, risks of debt vulnerability may be increased. Nevertheless, for many countries, these risks are moderate. We expect that they will not divert resources from these countries nor hinder their cooperation with Ukraine.

It is essential for Ukraine that its trading partners experience sustainable growth

The CEE countries have long had a significant share of Ukraine’s foreign trade. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, their share increased significantly—from 13% in 2021 to about 25% in 2022-2023. For this analysis of CEE economies, we considered Ukraine’s main trading partners outside the Eurozone: Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Hungary, and Czechia.

However, in the context of high interest rates, concerns about increasing risks of debt vulnerability are justified. According to the IMF‘s April WEO report, the share of emerging market (EM) countries, including the majority of CEE countries, in debt distress or at high risk in 2024 remains substantial.

According to an S&P representative, countries have not yet fully felt the impact of tighter global monetary policy, which is likely to persist for several years. Moreover, with each quarter where interest rates remain high, more countries find themselves in a difficult position, facing tough choices between servicing their national debts or investing in healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

In CEE countries, the risk of a fiscal crisis appears to be significantly lower compared to many other emerging markets. However, the size of the necessary fiscal adjustment to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio in certain countries, notably Romania and Hungary, is considerable. Any fiscal deviation could lead to an increase in the risk premium on government debt in the coming years.

CEE countries are expected to experience fiscal pressure over the next two years. Elections, defense spending, and interest expenditures will sustain high levels of budget deficits, with the highest interest burdens in Romania and Hungary.

Empirical data suggests that there is no universally optimal level of debt

The level of debt depends on a wide range of trade-offs and characteristics of the borrower. Safe levels of external debt in EM countries are low and highly dependent on the country’s macroeconomic management outcomes (Reinhart, Rogoff, and Savastano 2003).

Reinhart and Rogoff (2010) showed that economic growth was generally lower in both developed and EM countries, where government debt exceeded 90% of GDP. Cecchetti, Mohanty, and Zampolli (2011) found that economic growth declines for 18 OECD countries when debt exceeds 85% of GDP. Patillo, Poirson, and Ricci (2002) estimated that in EM countries, the impact of external debt on per capita GDP growth is negative when debt levels exceed 35-40 percent of GDP.

Regardless of its level, effective debt management involves ensuring a debt structure that is less vulnerable to changes in financial conditions and guarantees the preservation of macroeconomic and financial stability. Therefore, preference is given to obligations with longer maturities, fixed and low interest rates, and denominated in local currency.

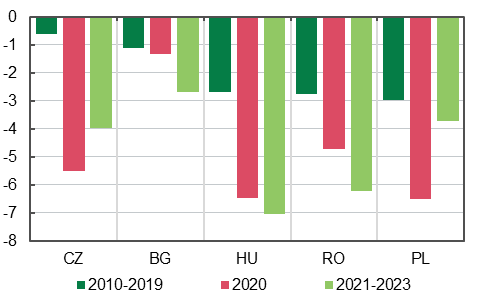

Chart 1. General Government Structural Balance (Deficit (-) / Surplus (+)) of Selected CEE Countries, % of GDP

Source: IMF.

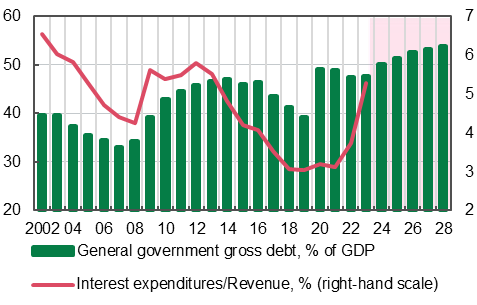

Chart 2. General Government Gross Debt and the Ratio of Interest Expenditures to Government Total Revenue in CEE Countries (Average)

Source: ECB, NBU calculations, IMF forecast.

The level of public debt in CEE countries has significantly increased over the past fifteen years, and the costs of servicing this debt have steadily risen as low-interest debt is repaid and replaced with new debt at higher interest rates.

Higher interest expenditures will reduce debt affordability, diminishing fiscal buffers. Moody’s expects the debt-to-GDP ratio to remain stable, but servicing costs will rise this year. Population aging, the transition to the “green” economy, and plans to increase defense spending (notably in Poland, to 4% of GDP) are factors indicating rising debt cost pressures in the future.

Overall, fiscal positions in CEE countries have weakened. The pandemic absorbed fiscal space and interrupted the process of fiscal consolidation. In CEE countries, the average fiscal response (i.e., support for businesses and households due to the pandemic) amounted to 14% of GDP in 2020-2021. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sharp rise in energy and food prices have further strained public finances.

Although inflation has somewhat eased and governments have started to consolidate public finances, the total and structural budget deficits remain high and exceed pre-pandemic levels. The increase in the budget deficit has led to a rapid expansion of public debt in CEE economies, which by the end of 2023 remains higher than pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, in some countries, the debt level was already very close to (in Poland) or exceeded (in Hungary) the IMF‘s threshold value (50% of GDP for emerging markets and 60% of GDP for developed countries) even before the pandemic, triggering the “high scrutiny” mechanism. This mechanism involves a debt sustainability analysis for countries requiring increased attention from the IMF (higher scrutiny countries), based on a comprehensive and detailed assessment of debt and the examination of various aspects of debt development using a wide range of table and charts.

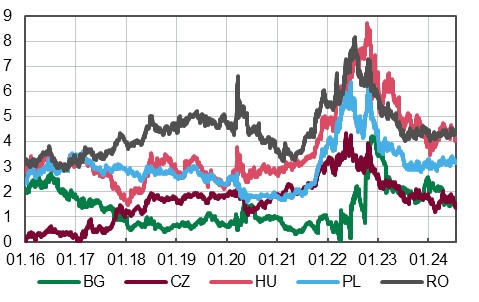

Chart 3. Yield Spread Between 10-Year Government Bonds in Germany and Selected local Countries (in national currencies), bps

Source: Refinitiv, NBU calculations.

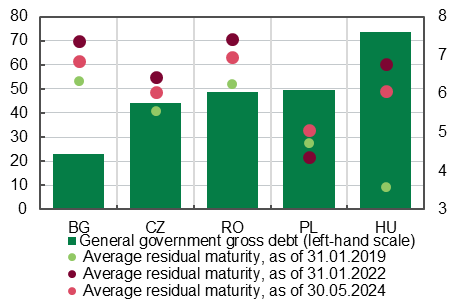

Chart 4. Average Residual Maturity for Total Government Debt Securities and General Government Gross Debt of Selected CEE Countries in 2023 (% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat, ECB.

Since 2022, significantly tighter financing conditions have squeezed already limited fiscal space

Because of tight monetary policy combined with increased risk premiums, the yields on government bonds have significantly increased. In most CEE countries, they peaked in October 2022. At the same time, for some of them, the spread with less risky German bonds reached or even briefly exceeded the high-risk threshold as perceived by the market – 600 bps (872 bps for Hungary, 816 bps for Romania, and 639 bps for Poland).

Given that CEE countries have a significant portion of their debt in foreign currency, there is a risk of increased debt vulnerability due to the uncertain trajectory of the Federal Reserve interest rates and the USD exchange rate. At the same time, the expected recovery of economic growth, despite geoeconomic fragmentation and increased trade protectionism, will help reduce the risk premium and increase investor attractiveness of assets in this group of countries.

The composition of debt securities due for revaluation in the medium term shows that both the maturity and level of debt have significantly increased (Chart 4). Despite this long-term positive trend, Poland has the shortest average residual maturity of government bonds at 5.1 years. Additionally, Poland and Hungary are the most vulnerable CEE countries to rising interest rates due to the high share of floating-rate securities in their outstanding debt instruments.

Hungary has the largest share of short-term (up to one year) securities in its public debt among the considered countries, while Bulgaria had no short-term securities as of the end of 2023. On average, the share of short-term securities in CEE is low at 1.9%.

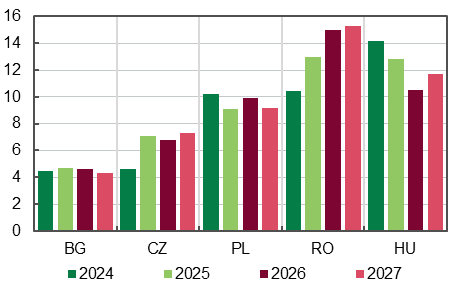

Gross financing needs of CEE countries are expected to average between 8.8 and 9.6 percent of GDP annually during 2024-2027, which is below the IMF’s high-risk threshold

The risk threshold for EM countries is 10% of GDP, and for developed countries, it is 15% of GDP. Among the high-risk countries are Romania and Hungary, where financing needs will exceed this threshold. Overall expenditure will slightly decrease in the future. However, the debt level for CEE countries is expected to moderately increase, averaging 53.4% of GDP in 2027, significantly higher than the pre-pandemic level of 39.2% of GDP in 2019.

Chart 5. Gross Financing Needs in Selected CEE Countries, % of GDP

Source: IMF.

Hungary, Poland, and Romania are expected to remain in the high-risk zone in the medium term, with their debt levels averaging 62.9% of GDP during 2024-2027. However, planned fiscal consolidation will reduce the need for budget deficit financing and slow the growth of refinancing costs, as well as ease access to international financial markets.

This level of debt burden for the CEE countries will not significantly divert resources or harm their cooperation with Ukraine

As Ukraine’s closest neighbors, CEE countries are highly invested in our victory. Although their assistance, considering the fear of reducing their own defense capabilities, is not as high in absolute terms as aid from the USA, the UK, and Germany, it is still crucial for Ukraine in today’s circumstances.

This primarily concerns already planned and approved aid programs. Notably, signing a memorandum between Ukraine and Romania, which includes increasing defense production capabilities and expanding ammunition production, as well as the agreement with Poland for joint weapon production, for which Poland has already allocated a loan, are important.

Ukraine and Poland have also signed a memorandum on cooperation in digital technologies and innovations, IT industry development, and more. The European Commission has adopted the “Interreg NEXT Poland-Ukraine 2021-2027” program to support cross-border development processes in the border area between Poland and Ukraine.

Czech support has shifted from supplying ready-made weapons to intensive defense industry cooperation, which the Czech Ministry of Defense plans to continue to develop. Among other, Czechia will provide Ukraine with a license to produce small arms and assist in establishing production of ammunition for these weapons in Ukraine.

A memorandum has been signed, and military cooperation with Bulgaria is expected to intensify, particularly through the Ukrainian-Bulgarian Commission on military-technical issues. This will increase the volume of military aid and initiate joint production of weapons and military equipment.

Additionally, a Romanian scheme to support investments in ports facing increased trade flows has been approved. Ukraine and Romania have signed an agreement that will enable the implementation of joint projects for the development of telecom infrastructure, digitalization, and cybersecurity.

Thus, a significant range of support areas for Ukraine that require direct involvement of CEE countries remains politically confirmed despite the potential increase in debt burden risks for these countries.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations