We find that labor market regulations change was the second most important force of economic growth for the period 1995−2014. Relatively rich countries benefit more from labour market liberalization than poorer ones. At the same time, easing of labor market regulations affects growth more in countries where labor markets are less liberalized. Thus, countries with high labour market rigidities will be largely rewarded for easing those rigidities.

Why consider reforms of the labor market

There are different components of the labor market reforms and they are implemented with a view of improving the labor market conditions. Some reforms are directed toward the regulation of hiring and firing and minimum wage. Others regulate collective bargaining, hours, and costs of worker dismissal or employment protection for temporary contracts. Different reforms have different labor market-related goals. The basic idea of reforms is that they have a liberating effect on the labor market. The most important link investigated in the literature is the relationship between labor market regulations and unemployment and the rate of participation in the labor force. There is a consensus in the literature that increasing labor market flexibility results in both larger employment and participation rates.

Such an outcome is expected given the design of the labor market reforms. Since labor is an essential input in wealth generation, it is important to also investigate what effect do reforms of the labor market have on productivity growth. The reduced form regression analyses provide an ambiguous answer to this question. This type of analysis, however, does not model the channel through which labor market regulations affect economic growth and therefore can be misleading. Badunenko (2018) uses previous findings by Bassanini and Ekkehard (2002) and Botero, Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de Silanes, and Shleifer (2004) to argue that labor market regulations have an allocative efficiency-enhancing role when allocating workers to the best employment outcomes. Conceptually, labor productivity is decomposed into effects attributable to change in efficiency, technological change, capital deepening, human capital accumulation and change in labor market flexibility. This decomposition allows quantifying the isolated effect of changes in labor market regulations on labor productivity growth.

[Changes in] the labor market regulations

Data

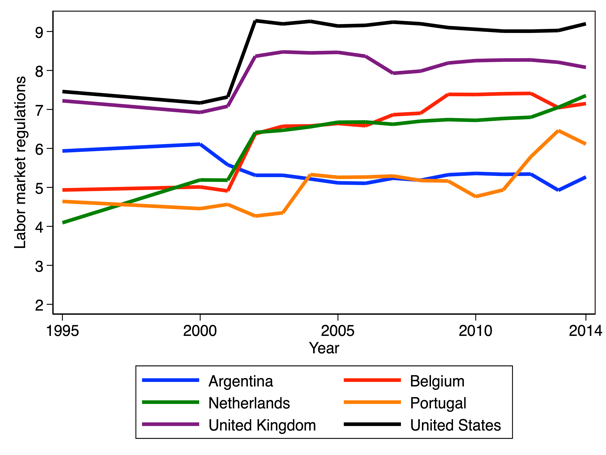

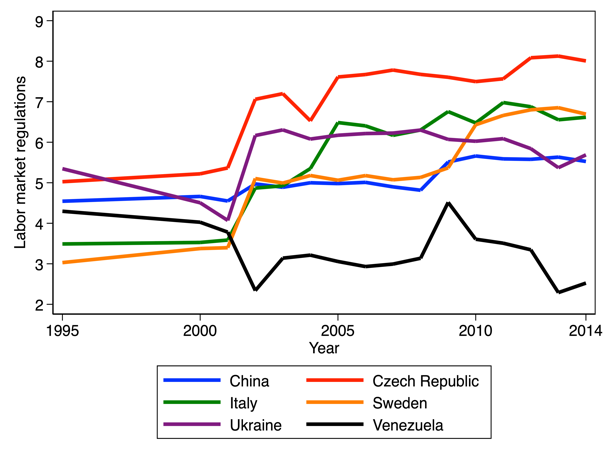

The analysis is performed for 52 countries over 1995-2014, for which comprehensive data on output and inputs required for estimation of the production function are available. The data for labor market regulations are taken from the Fraser Institute (Gwartney, Lawson, and Hall, 2016). The index ‘Labor market regulations’ ranges from 0 to 10 and is calculated as a simple average of six components: (i) hiring regulations and minimum wage, (ii) hiring and firing regulations, (iii) centralized collective bargaining, (iv) hours regulations, (v) mandated cost of worker dismissal and (vi) conscription. The index measures how flexible labor market is, hence it is called LMF (labour market flexibility). The closer the index is to 0, the more rigid is the market. Higher index implies greater labor market flexibility. The evolution of the index for selected countries is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Labor market regulations index.

Source: Gwartney et al., 2016

Several observations stand out. First, the US and the UK seem to have the most liberal labor market. Second, labor markets are more liberalized in 2014 than they were in 1995. Third, European countries were gradually making their labor market less rigid, but at a very moderate pace. Finally, the labor market in some countries has become even more regulated.

The index from the Fraser Institute is criticized, as are other indices, and makes case for careful interpretation of an analysis based on this index. Although an index that is obtained by aggregating different types of data (the above six components come from both survey and hard data), contains noise, the robustness analysis using an index that excludes the conscription component has also been performed and the conclusion qualitatively remain the same: positive changes in the labor market manifest themselves in productivity gains.

Contribution to labor productivity growth. The average productivity growth over 1995-2014 was 61.8%, which is about 2.56% per annum. The following table shows the aggregated results of the analysis, where productivity growth is decomposed into five components:

- change in efficiency or a catch-up component, which tells us about the change of the relative distances to the production frontier in 1995 and 2014;

- technological change, or how much the production frontier shifted;

- capital deepening, or the increase in the capital-labor ratio;

- human capital accumulation, or the change in the human capital index; and

- the change in labor market flexibility index.

Since the decomposition is based on indices, the components are unit independent and are therefore comparable to one another in terms of magnitude.

Table 1. Percentage contributions of components of the quintipartite decomposition to labor productivity growth

| Measure | Contribution of | ||||

| change in efficiency | technological change | capital deepening | human capital accumulation | change in labor market flexibility | |

| LMF | 54.50 | 14.00 | 84.09 | 21.42 | 34.98 |

| LMF2 | 45.02 | 8.40 | 85.35 | 20.95 | 30.33 |

Table 1. shows that labour market flexibility as measured by the Fraser institute index (LMF) contributed 35% to labour productivity growth, and if measured as the same index without the conscription component (LMF2), its contribution is 30%

It is most remarkable that the failure to catch up with the world-wide frontier, which shifted from 1995 to 2014, is the reason that countries’ productivity did not grow even more. Only 4 countries, Ukraine, Russia, Jordan, and Norway got more efficient. Capital deepening is by far the major contributor to labor productivity growth. This finding confirms that of many researchers who performed a cross-country analysis. The second most important source of labor productivity growth is the change in labor market flexibility. The contribution of human capital accumulation is the third largest. Finally, only a handful of countries benefited from a change in technology and so it is the smallest force behind labor productivity growth overall. Most importantly, the findings hold whether the labor market flexibility index is based on 5 or 6 components.

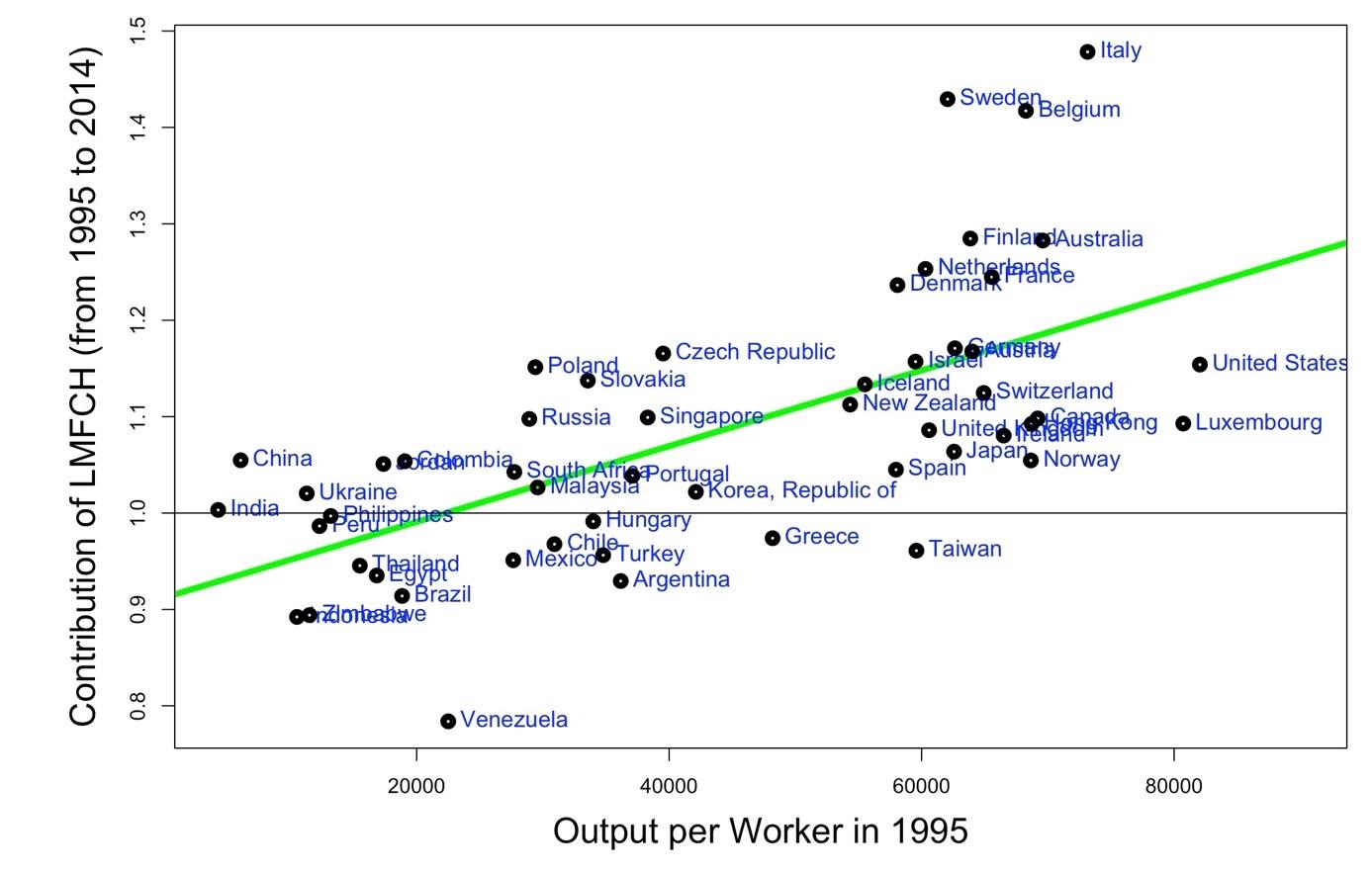

When is the effect of the reform the largest? The first conclusion we derive from the analysis is that making the labor market more flexible is beneficial for economic growth. The question is whether this effect is uniform in the sense that all countries benefit from labor market reforms to the same extent. To answer the question if relatively richer countries benefit more from labor market reforms, figure 2 plots the change of labour market flexibility contribution to labor productivity growth from 1995 to 2014 against initial labor productivity measured as output per worker in 1995.

Figure 2. Contribution of LMFCH plotted against output per worker in 1995.

Notes: Green solid line is the regression line. The slope coefficient is statistically significant at 1%.

The value of contribution on the vertical axis of 1 in Figure 2 implies zero contribution (i.e., (1-1)*100%). The value above 1 implies positive and the value below 1 means a negative contribution of the changes in labor market flexibility to labor productivity. The positive and statistically significant slope in Figure 2 presents evidence that countries that were more productive in 1995 have benefited more from labor market reforms than countries that were less productive in 1995.

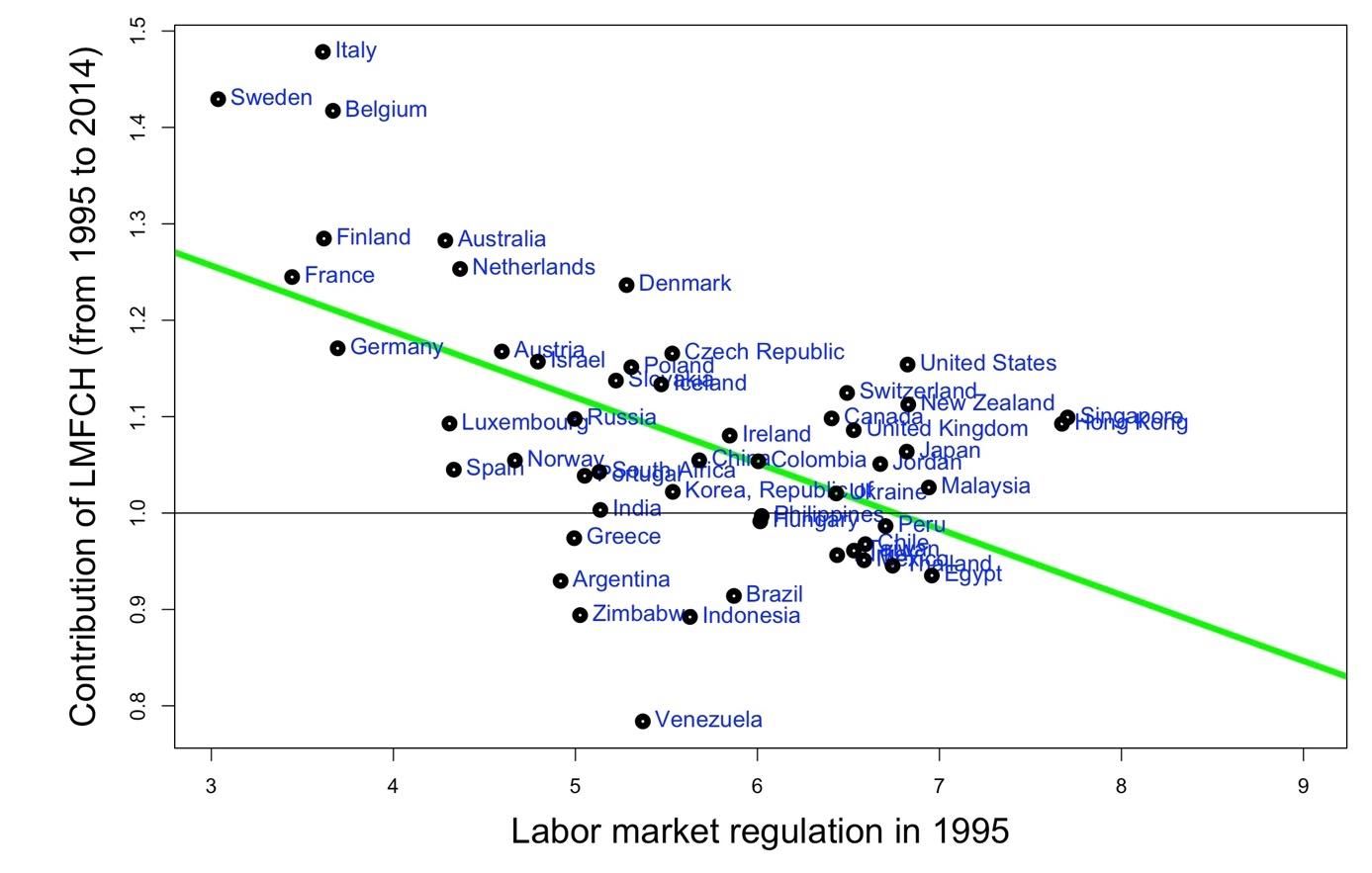

To see if countries with a low base of labor market flexibility have benefited more from the changes in labor market flexibility, figure 3 plots the LMFCH contribution to labor productivity growth from 1995 to 2014 against the initial labor market flexibility index in 1995.

Figure 3. Contribution of Labour Market Flexibility Change (LMFCH) to productivity growth plotted against the labor market flexibility index in 1995.

Notes: Green solid line is the regression line. The slope coefficient is statistically significant at 1%.

The slope coefficient of the regression line in Figure 3 is negative and statistically significant at all conventional levels. The regression suggests that labor productivity in countries with initially more rigid labor markets has increased more from changes in labor market flexibility than in those whose labor market was initially more liberalized.

Reforms of the labor market and economic growth

The discussion of the need to perform the labor market reforms is not new. See, for example, a discussion on youth unemployment or labor market reforms past 2014. The conclusions of the analysis in this publication should be interpreted in a very straightforward way since only one link has been investigated: for flexible labour market increases productivity. However, there are limits to what can be achieved by loosening the labor market rigidities since policymakers have multiple societal objectives. Some of these objectives go beyond economic growth such as for example reducing poverty and inequality, or increasing social security. Thus, reforms that increase labour market flexibility should be accompanied by policies helping those most in need to join the labour force or, if that is impossible, to live a decent life.

References

Badunenko, Oleg “Labor Market Regulations and Growth,” in “The Political Economy of Structural Reforms in Europe,” Edited by Nauro F. Campos, Paul De Grauwe, and Yuemei Ji, Chapter 8, Oxford University Press, New York, 2018. Print ISBN-13: 9780198821878 DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198821878.001.0001

Bassanini, Andrea and Ernst, Ekkehard, “Labour market regulation, industrial relations and technological regimes: a tale of comparative advantage,” Industrial and Corporate Change, June 2002, 11(3), pp. 391–426.

Botero, Juan C., Djankov, Simeon, La Porta, Rafael, Lopez-de Silanes, Florencio and Shleifer, Andrei, “The Regulation of Labor,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, November 2004, 119(4), pp. 1339–382.

Gwartney, James, Lawson, Robert and Hall, Joshua, “2016 Economic Freedom Dataset, published in Economic Freedom of the World: 2016 Annual Report,” 2016, Publisher: Fraser Institute.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations