At the beginning of 2015, the Ukrainian president approved the Strategy 2020 program, a strategy which includes 25 key performance indicators (KPI) which can be used to assess Ukraine’s progress in implementing the strategy program.

In a series of upcoming posts we will evaluate how likely it is that Ukraine will reach some of these KPIs by 2020. The first KPI we evaluated was ‘winning 35 medals at the 2020 Summer Olympic Games in Japan’. Here we evaluate the goal of ‘being in the top 50 of the PISA ranking’.

Background

The Strategy 2020 Program would like to see Ukraine in the top 50 of the ‘Programme for International Student Assessment’ (PISA) ranking of educational quality. A country’s PISA score is based on the performance of 15 year old students on tests in Math, Science and Reading.

So far Ukraine has never participated in the PISA study but hopes to have its first ever test results available in 2018. How many countries will have PISA scores in 2018 is unclear but according to the PISA website more than 70 countries are participating the most recent 2015 wave while 65 countries participated in the 2012 wave.

Progress so far

While Ukraine is not included in the PISA ranking, several indicators exist that can give us some idea of the quality of Ukraine’s education.

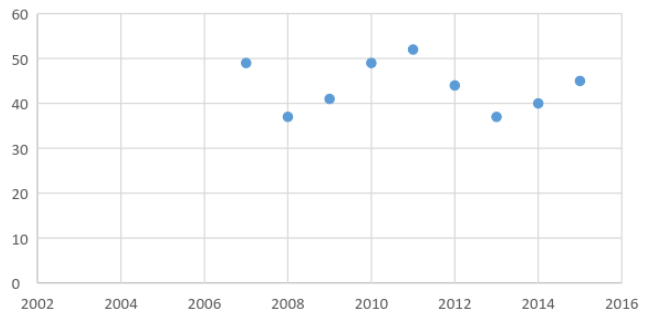

First, one question in the Executive Opinion Survey of The World Competitiveness report asks business leaders about the quality of primary (not secondary) schools in their country [1]. Over the years, data are available for between 131 and 148 countries, with Ukraine ranking between 37th and 52nd.

Fig 1. Ukraine’s rank in terms of Quality of Primary Education, as measured by the World Competitiveness Report

Source: Global Competitiveness Dataset 2006-2015. Question: In your country, how do you assess the following: a. Quality of primary schools [1 = extremely poor – among the worst in the world; 7 = excellent – among the best in the world]

Second, the World Competitiveness report also asks about the quality of math and science education (fig. 2). On this question, Ukraine ranks between 28th and 45th. Neither indicators show Ukraine’s ranking is deteriorating consistently over time, suggesting the goal of being in the top 50 in PISA does not seem a particularly ambitious goal, especially given that the PISA ranking includes only 65 to 70 countries while the World Competitiveness report ranks over 130 countries.

Fig 2. Ukraine’s rank in terms of Quality of Math and Science Education, as measured by the World Competitiveness Report

![Source: Global Competitiveness Dataset 2006-2015. Question: In your country, how do you assess the quality of math and science education? [1 = extremely poor – among the worst in the world; 7 = excellent – among the best in the world]](https://voxukraine.org//wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ed-pic-2-1.png)

Source: Global Competitiveness Dataset 2006-2015. Question: In your country, how do you assess the quality of math and science education? [1 = extremely poor – among the worst in the world; 7 = excellent – among the best in the world]

Third, while Ukraine is not included in PISA, Ukraine did participate in another international study, ‘The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study’ (TIMSS) test in 2011. While PISA tests 15 year olds on math and science, TIMMS tests 8th graders (13-14 year olds) in these subjects. In 2011, Ukraine ranked 19th out of 45 countries in TIMMS for Math and 18th for Science.

Not surprisingly, countries’ results in PISA closely track countries’ results in TIMMS. Below we present the results of a regression analysis of PISA results on TIMMS results for the 28 countries which were participating both in the 2012 wave of PISA and the 2011 wave of TIMMS. Given Ukraine, participated in the 2011 wave of TIMMS, the estimated regression equation allows us to predict the score Ukraine would have had if Ukraine had participated in 2012 in PISA, and hence estimate the rank Ukraine would have had at that moment.

Table 1. Regression of PISA Scores on TiMMS Scores

| Math | Science | |

| Constant | 55.96 | -22.04 |

| (28.82) | (39.13) | |

| Coefficient of TiMMS Score | 0.84 | 1.00 |

| (0.06) | (0.08) | |

| Adj. R2 | 0.89 | 0.86 |

| # | 28 | 28 |

| Ukraine’s predicted score | 460.0 | 478.6 |

| Ukraine’s predicted PISA rank in 2012 | 42 | 39 |

Table 1 indicates that for Math, the PISA Score equals 55.96 + 0.84*the TiMMS Score. Given that Ukraine for Math had a TiMMS score of 479, Ukraine’s expected PISA score for Math is 460 (55.96+0.84*479). In 2012, a score of 460 would be good for place 42 (out of 65) in the PISA ranking. Similarly, for Science, Ukraine’s predicted score is 478.6, which would be good for place 39 (out of 65) [2]. Again, this suggests that aiming for a top 50 position in the PISA ranking is not very ambitious.

Is it possible for Ukraine to reach this goal?

The above discussion suggests that aiming for a top 50 position in the PISA ranking is a fairly save target. And it suggests that if one wants to use the PISA ranking as benchmark, Ukraine might want to aim for, for example, a top 40 (or even top 35) place rather than a top 50 place.

Is this measure the best measure of educational performance?

The Strategy 2020 program motivates the inclusion of the PISA KPI as follows:

“Ukraine will participate in PISA international education quality survey and will rank among top 50 countries in the world. This will mean that school graduates will possess all necessary skills to successfully compete on international arena and will be able to continue high education.”

As pointed out by some earlier VoxUkraine columns (link 1, link 2) Ukraine’s educational system does not match the needs of its economy well, that is, despite their many years of education, the productivity of Ukrainian employees is not that high. This is confirmed by the fact that, unlike what the 2020 strategy assumes, Ukraine’s relatively good score on the World Competitiveness Report’s math and science education ranking does not go together with a good score, in the same Report, on how well Ukraine’s educational system meets the need of a competitive economy. Fig. 3 shows that Ukraine’s rank in terms of how well its educational system meets the need of a competitive economy is worse than its ranks on other educational indicators and has been deterioration quickly over time, from a rank of about 50th to a rank of about 70th.

Fig 3. Ukraine’s rank in terms of Quality of the Educational System in meeting the needs of a competitive economy, as measured by the World Competitiveness Report

![Source: Global Competitiveness Dataset 2006-2015. Question: In your country, how well does the education system meet the needs of a competitive economy? [1 = not well at all; 7 = extremely well]](https://voxukraine.org//wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ed-pic-3-1.png)

Source: Global Competitiveness Dataset 2006-2015. Question: In your country, how well does the education system meet the needs of a competitive economy? [1 = not well at all; 7 = extremely well]

Hence, as a KPI, Ukraine could aim to be in the top 50 on the ‘meeting the needs of a competitive economy’ indicator [3].

Of course, this latter indicator has the drawback of being an indicator based on the perceptions of a fairly small number of people (about 100 Ukrainian business leaders in case of the Ukrainian score [4]) unlike PISA which is based on test scores of a fairly large sample of Ukrainian students. Perception rankings have the disadvantage of being more easily manipulated and given the small sample used might not give an accurate picture of the real situation in a country. That being said, perception rankings have the advantage they can reflect reforms right away even if the real impact of these reforms might take time to show up in test scores.

Summarizing, if one uses the rank in PISA as a KPI, the Strategy 2020 might well want to be more ambitious and aim to be in the top 40, rather than aiming to be in the top 50 of the PISA rank as is currently the case. Aiming to be in the top 50 is a reasonable goal for the ‘meeting the needs of a competitive economy’ indicator. Given the drawbacks of both indicators, aiming to meet both indicators at once might well be the best KPI.

Notes

[1] For Ukraine, about 100 business leaders were surveyed

[2] In 2009, more than seventy countries participated in PISA but even then these scores would still be good for a rank around the 40th place as countries that regularly participate in PISA are high income/high educational quality countries

[3] PISA is a very useful instrument for educational policy analysis and Ukraine should participate in this survey, even if a specific place in the PISA ranking would not be a KPI

[4] The Global Competitiveness Index which includes this indicator is used as another KPI in the Strategy 2020 document

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations