The hryvnia appreciated from 28 UAH/USD in September 2018 to 24 by UAH/USD now. This 15 percent appreciation is a new experience for many Ukrainians. Naturally, there are questions about whether this is a good trend and what the government and the central bank should do about it. While this post is not going to give an exhaustive treatment of these questions, the goal here is to provide a historical as well as international perspective on these developments for better understanding of the options.

Historical background

Like Ukraine, many countries have had periods of high inflation. Although the details of why high inflation happened vary across countries and times, the recipe for bringing inflation under control is remarkably simple: a credible, tight monetary policy implemented by an independent central bank (with occasional help from a responsible fiscal policy). In practice, this means that the central bank has to maintain interest rates well above actual or expected inflation for some time. The mechanism is simple. High real interest rates (the difference between the nominal interest rate and expected inflation) can affect the economy via many channels. For example, households and firms may find the cost of borrowing high and thus postpone or reduce their spending. High real interest rates can lead to appreciation of the domestic currency thus reducing the competitiveness of exporters, leading to a slower growth of wages and ultimately cooling domestic demand. The higher the real interest rate is, the more depressed domestic demand and economic activity is going to be. As the economic activity cools down, inflation pressures subside. In short, to achieve lower rates of inflation in the long-run, countries have to go through recessions or at least a period of below-potential economic growth. How high real rate should be and for how long should real rates be elevated? This is where the specifics matter and this is where Ukraine can learn from other countries.

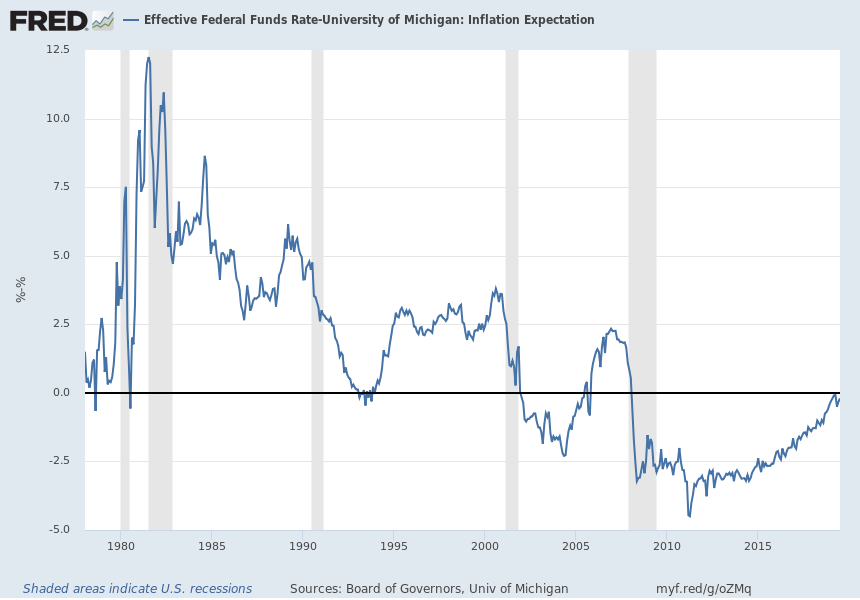

Consider the U.S. experience of reducing inflation from double-digits in the 1980s to 3-4% inflation. To decrease inflation, the Federal Reserve (the central bank in the U.S.) started to increase interest rates in the late 1970s to unprecedented levels. Figure 1 below shows that the real rate increased to more than 7% by 1980 which pushed the economy into a recession. Inflation started to fall. Because the economy was weak, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) started to cut nominal rates aggressively to stimulate the economy thinking that inflation is under control. However, this aggressive policy response sent a wrong signal: economic players started to believe that the Fed is not serious about inflation. As a result, despite the weak economy, inflation started to increase! Now the Fed had to deal with a double problem: weak economy and high inflation. Paul Volcker, the chairman of the Fed, had a mandate from Presidents Carter and Reagan to exterminate inflation. Given this political support, the Fed decided to fight inflation by raising interest rates to even higher levels: by 1982 the real interest rate reached astounding 12.5 percent. This very tight monetary policy pushed the economy into a recession again. In fact, it was the worst recession between World War II and the Great Recession in 2007-2009. However, this time the Fed learned the lesson and did not rush to cut interest rates. Figure 1 shows that real rates were gradually falling from 1982 to 1988. This period of elevated real interest rates broke the back of inflation in the U.S. Households, firms, financial markets and other economic players were convinced that the Fed is serious about keeping inflation in check.

After this successful disinflation, the U.S. economy had a very strong expansion for many years. This hard-earned credibility was also highly instrumental in fighting subsequent recessions. For example, in response to the Great Recession of 2007-2009, the Fed kept real rates at ultra-low levels but this highly accommodative policy did not spark inflation. Likewise, the negative real interest rates during the 2001 recession did not result in a runaway inflation. Why? Because everybody knew that if there is inflation on the horizon, the Fed will nip it in the bud.

This experience in the U.S. has important lessons for Ukraine. First, to conquer inflation, the central bank has to keep monetary policy tight for quite some time. Second, relaxing a tight monetary policy prematurely may be costly because economic agents may start to believe that the central bank is not focused on price stability. To re-establish credibility, the central bank may have to implement an even tighter monetary policy and thus generate a painful economic slowdown or even a downturn.

Figure 1. Real interest rate in the U.S.

Ukrainian experience

For most of its history, Ukraine operated under the fixed exchange rate and only recently the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) adopted inflation targeting and a flexible exchange rate as its policy framework. After the spike of inflation in 2014-2015, the central bank has been trying to reduce inflation and bring it eventually to the NBU’s 5 percent inflation target. This process was not easy given the banking and currency crises, recession, and war.

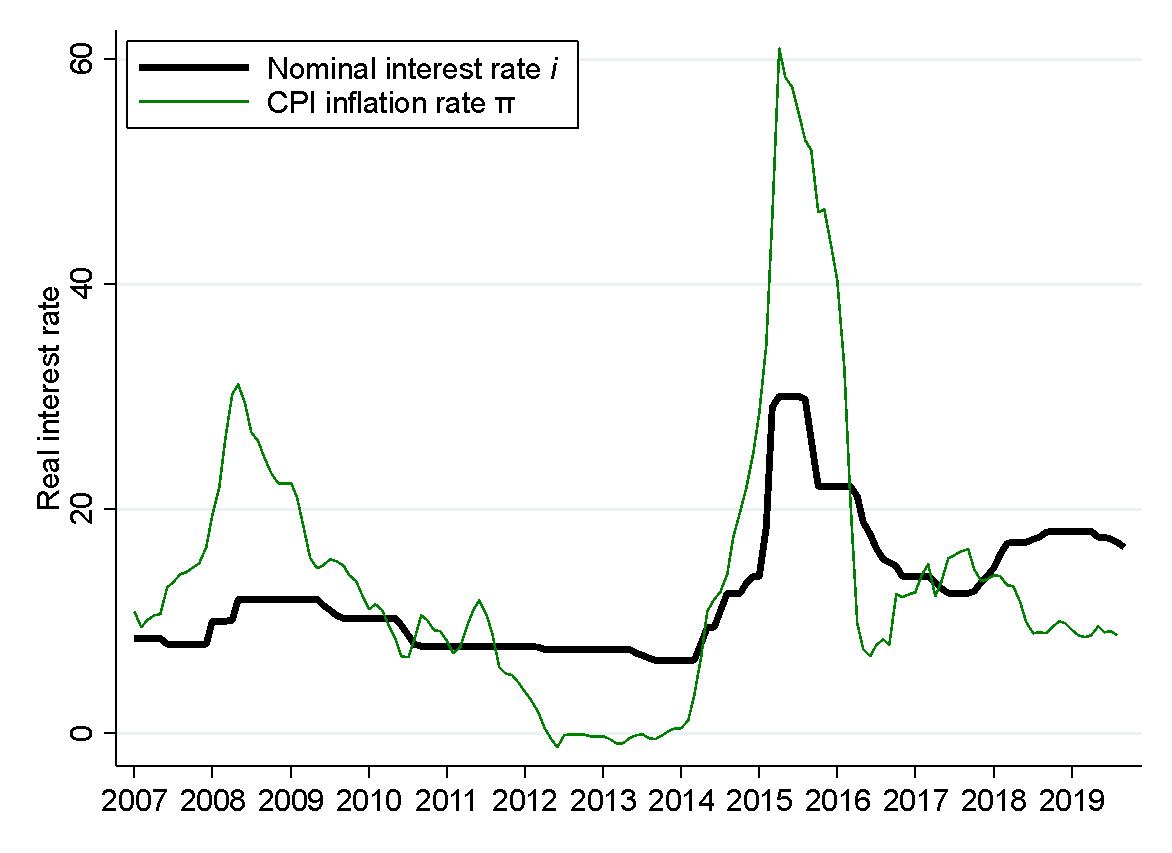

Figure 2 shows that the NBU dramatically raised its policy rate (“oblikova stavka”) in 2015. This period of very high nominal rates was short-lived however. By mid 2017, the NBU reduced the rate to less than 13 percent. Because inflation pressures were building up and the central bank was concerned about missing its inflation target, the interest rate was raised again. In 2019, the NBU started a new cycle of interest rate cuts.

Figure 2. Inflation rate and NBU policy rate (nominal)

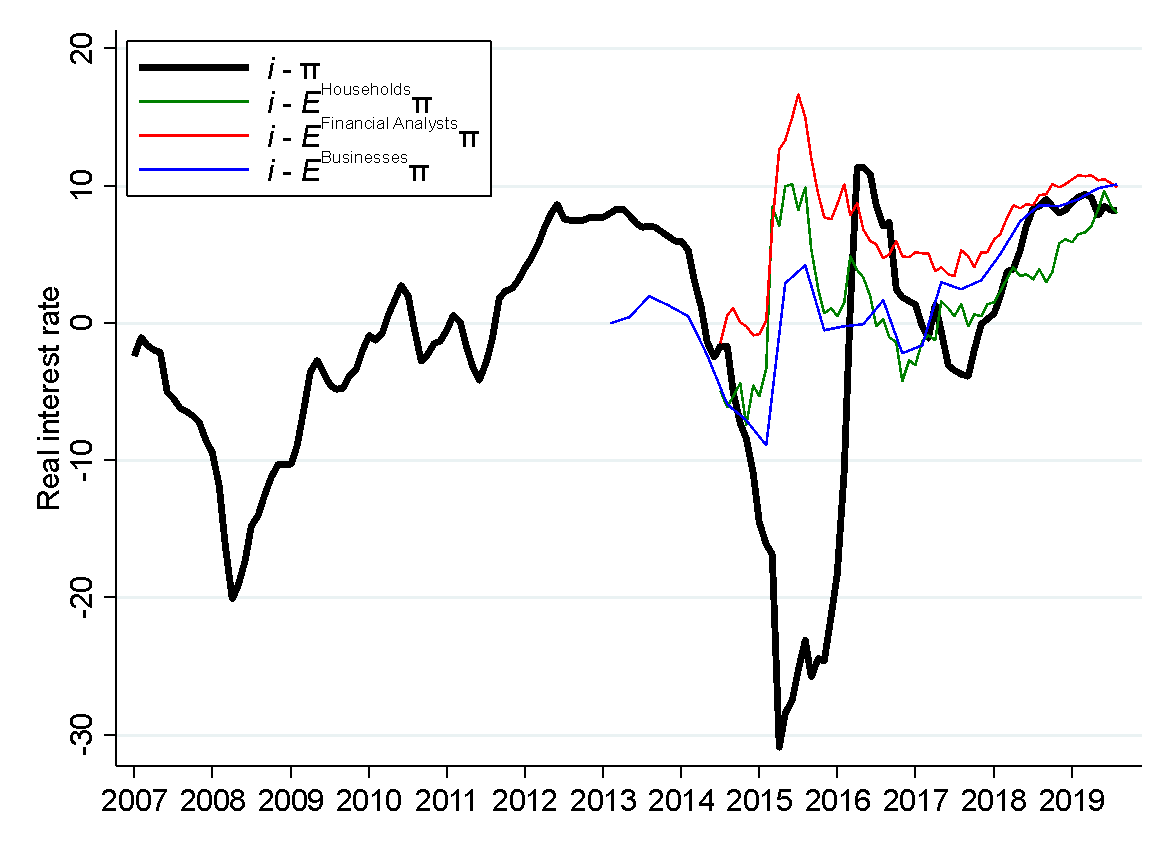

To better understand the importance of this dynamic, Figure 3 shows the time series of the real interest rate since 2007. Notice that, despite high nominal interest rates, the real rate perceived by businesses (equals to nominal rate minus inflation expectations of businesses, blue line) and households (nominal rate minus inflation expectations by households, i-EHouseholds, green line) was negative in 2016-2017. In other words, monetary policy was not as tight as one may infer from high nominal interest rates. Consistent with this low real interest rate, inflation started to pick up. As the NBU raised the real interest rate in 2017-2018, inflation decelerated. Importantly, while the NBU is cutting the nominal interest rate now, the real rate remains at roughly 10%. That is, monetary policy continues to be tight.

Figure 3. NBU real interest rate.

Notes: i is the NBU policy rate (“oblikova Stavka”). is actual CPI inflation over the previous 12 months. EX is one-year ahead expected inflation rate for agent X. Expectations for these agents are reported: households (GfK Survey of Households), businesses (an NBU survey), and financial analysts (an NBU survey).

Mechanism

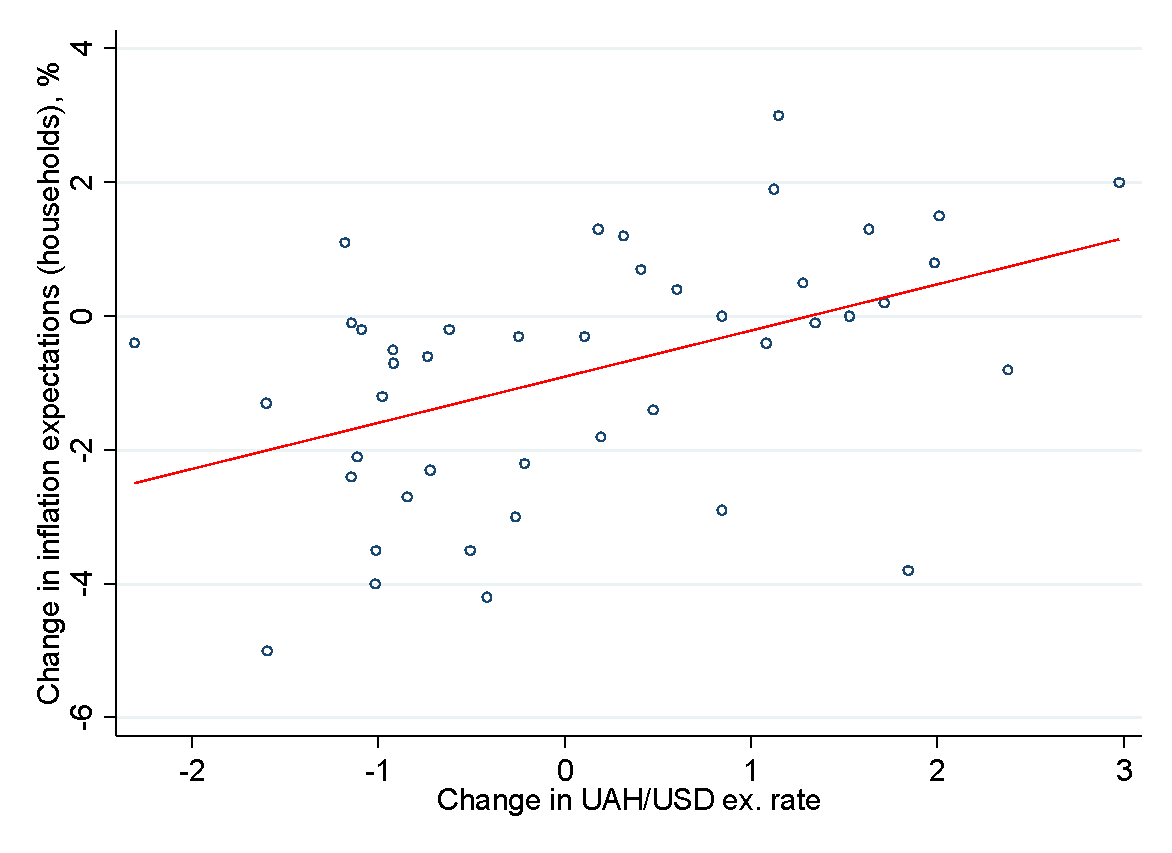

Is it necessary to keep interest rate high and have a strong hryvnya? A key element of any disinflation is a reduction of inflation expectations, a main determinant of actual inflation. Intuitively, to reduce inflation now, the central bank must convince economic players that inflation will be lower in the future. Previous research suggests that inflation expectations of Ukrainian households and businesses are very sensitive to changes in the hryvnya/dollar exchange rate. Figure 4 shows that since the end of the 2014-2015 crisis there is a stable relation between them. If the exchange rate increases by one hryvnya (e.g., from 25 UAH/USD to 26 UAH/USD), households expect inflation to increase by 0.7 percentage points. Because high real interest rates attract significant foreign capital flows, the hryvnya appreciated. The size of this appreciation can account for nearly 3 percentage point (4×0.7) decline in inflation expectations. Thus, appreciation of the hryvnya – a consequence of tight monetary policy – is a part of how the NBU reduces inflation, and now the NBU is on track to hit its 5% inflation target in a year or two.

Figure 4. Exchange rate and households’ inflation expectations, 2015Q3-2019Q3

Notes: the figure shows the relationship between changes in the UAH/USD exchange rate (horizontal axis) and changes in inflation expectations (vertical axis). All changes are measured as three-month differences (e.g., April value of a variable minus January value of the variable) to reduce noise.

Conclusions

There is a striking parallel between the U.S. and Ukrainian experiences. To reduce inflation, the central banks generated “stop-go” policy cycles: a period of highly tight monetary policy (to reduce inflation at the cost of a depressed economy) was followed by a temporary relief (to stimulate the economy) which in turn was followed by another cycle of tightening/loosening of monetary policy with real rates being as high (if not higher) as in the first policy cycle. With the benefit of hindsight, one may say that this volatility could have been avoided if policy rates were not reduced too early in the first place. We could have had lower inflation in Ukraine now if real interest rates remained elevated for a bit longer after the inflation spike.

Clearly, a strong hryvnya can hurt exporters, slow down economic growth, and reduce tax revenue of the government. And the NBU can lower interest rates and actively intervene in the foreign exchange market to reduce these adverse effects. But one should understand that the cost of doing so is going to be another round of high inflation, tight monetary policy, and economic slowdown. The ultimate result will be wasted time and unnecessary macroeconomic volatility, which makes Ukraine less attractive for investment and depresses consumer spending (think about Argentina that goes through these cycles all the time). In other words, pressuring the central bank to reduce rates can backfire.

The art of optimal policy is to balance these risks to make interest rates just high enough for the period just long enough to have a smooth transition to a low-inflation environment so much needed for sustainable economic development of Ukraine. This calls for patient, calculated policy-making not only for the central bank but also for the government. The process of disinflation must be finished now rather than later.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations