Inflation doesn’t grab much attention of Ukrainians until it breaks the 10 % line – but the moment it does, Google searches and even Verkhovna Rada speeches about it spike, then quickly fade while prices keep climbing. This short spike of attention shows that attention is a measurable economic force: it moves expectations, shapes policy windows, and reminds economists that knowing when people first notice a statistic – and how quickly their interest fades – can be just as important as the number they are reacting to.

Do you know what the official inflation rate in Ukraine is right now? If yes – well done; you probably use that figure at work or when deciding where to put your money. If not, you’re in good company: none of my friends, and even most classmates in an economics program, could recall current inflation on the spot. A few guesses were so low they stunned me – one person said 4 %.

When Attention to Inflation Switches On

Yet inflation is one of the core numbers in economics. It shows up in almost every model we study, from simple AD–AS diagrams to corporate valuation spreadsheets. Firms watch it when setting wages, prices, and investment plans; households weigh it when choosing between a hryvnia deposit and dollar savings, taking a mortgage, or asking for a raise. Government budgets, pensions, and social payments are all indexed to it, and most modern central banks treat price stability as their primary mission, guiding all interest-rate decisions. In the United States, an Oxford Economics analysis of the 2024 presidential race argues that voters’ focus on inflation played a major role in Donald Trump’s return to the White House.

So why, when it now takes only a few seconds to look up the latest figure (and many of you probably googled it right after my question and saw the number almost instantly), do most people still skip checking it altogether?

Economists call this habit rational inattention – the idea that people have limited mental bandwidth and will follow a variable only when the payoff exceeds the effort of tracking it. Christopher Sims, a Nobel laureate in economics, formalised the concept two decades ago, treating attention as a scarce resource that decision-makers allocate much like income or time. The logic shows up in everyday life: we check the weather app only if we plan to leave the house, compare petrol prices when the tank is close to empty, and glance at the exchange rate movements before a holiday – information is free and constant, but we pull it in only when it matters right now.

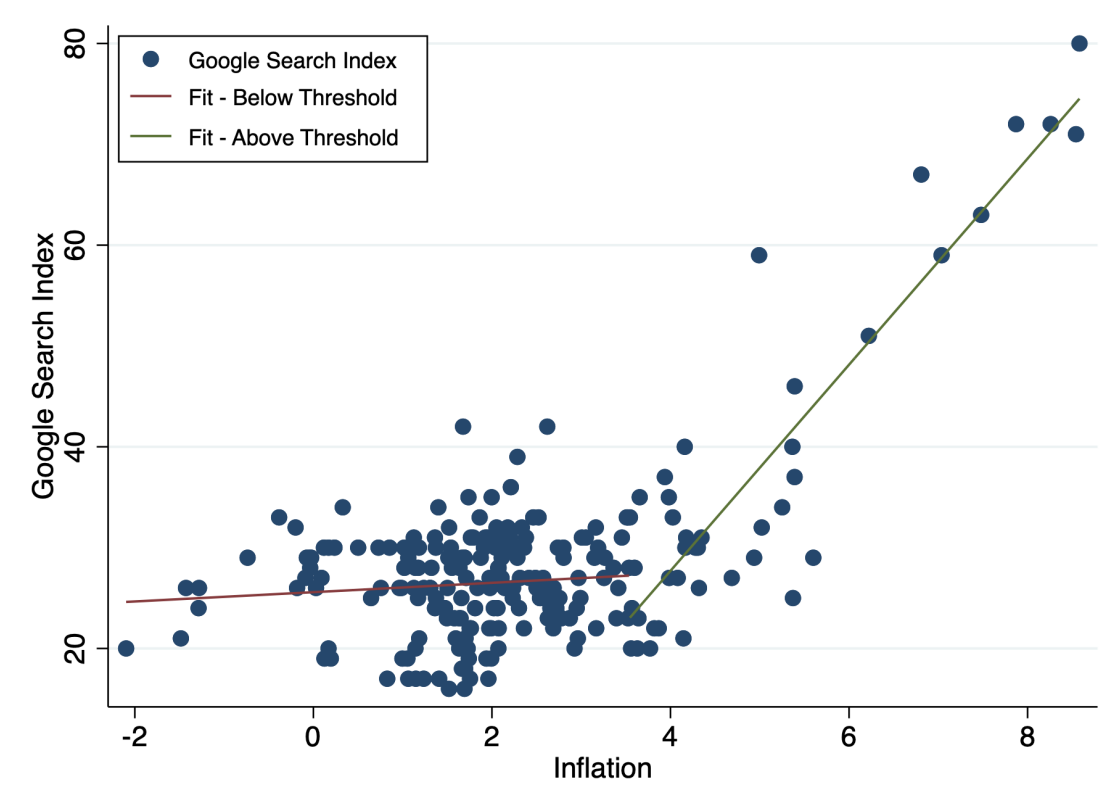

The same happens with inflation: when price growth drifts along at 1–3 % a year – only a few tenths of a percent each month – the change is too subtle to stand out. A weekly shop might cost just a little more, a difference most people barely notice. Recent empirical work confirms the point. In the United States, attention to inflation captured through Google searches, Twitter posts and newspaper references remains flat until annual inflation stays at 3–4 %. However, as Figure 1 shows, once inflation moves beyond that range, attention rises in a clear, statistically significant upward trend with each additional percentage point (Korenok et al., 2023). A parallel study for the euro area (Buelens, 2024) finds national triggers clustered around 2–4 % and the same steady rise in online searches and media coverage once the threshold is crossed. Economists label this tipping point the inflation-attention threshold – the moment when keeping an eye on prices finally feels worth the effort.

Figure 1. Threshold model fit for the U.S. from Korenok et al., 2023 (Threshold = 3.55 %)

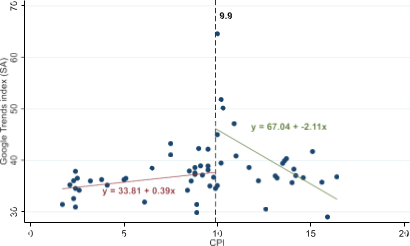

Ukraine’s Double-Digit Trigger

The Ukrainian case is different. Long stretches of our recent past have been so noisy that price news never makes the top of the queue. Take 2014–2016 – the early Donbas fighting, nightly updates on shelling, the hryvnia’s free-fall, wage delays and queues at cash machines – headline inflation rocketed above 50 %, yet Google searches for “inflation” hardly moved. To better hear inflation’s own signal, I drop those crisis years and run the threshold model on the quieter 2017–2022 window (Figure 2). A monthly Google-Trends index (index measures the relative popularity of a search term over time, scaled from 0 to 100 based on its proportion to all searches in a given region and period) of inflation queries is paired with official CPI data and examined using a single-threshold regression that allows the slope to shift once attention switches on. The break point is at 9.9 %: search interest rises slowly through single digits, jumps the moment CPI turns two-digit, then fades while prices keep climbing.

Figure 2. Google search interest and estimated inflation threshold (Jan 2017 – Jan 2022)

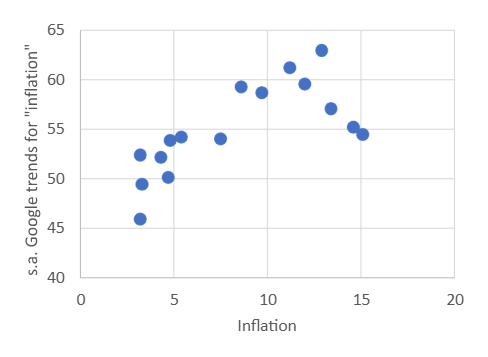

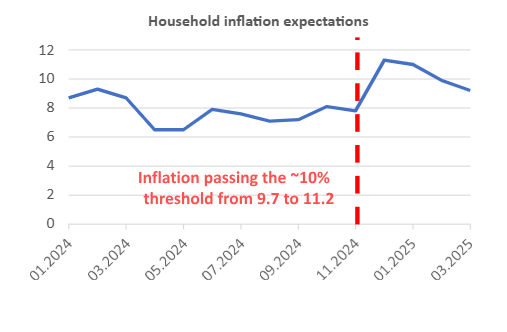

Fresh data for January 2024 – May 2025 repeat the same script (Figure 3) – curiosity builds into the 10 % mark, peaks just beyond it, and levels off even as inflation pushes toward the mid-teens. In Ukraine, the inflation-attention threshold sits right at the first double-digit print – once that flash passes, other headlines take over.

Figure 3. Google search interest and inflation level (Jan 2024 – May 2025)

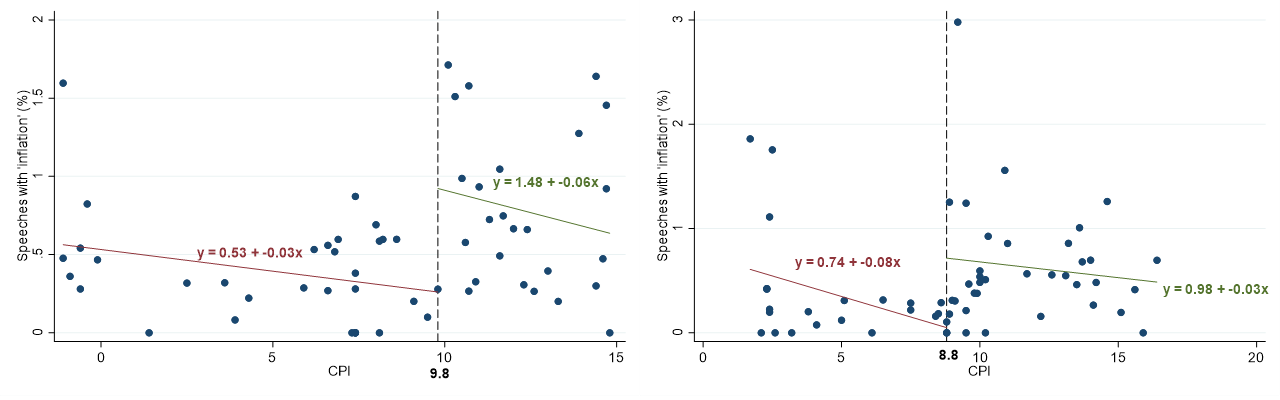

To cross-check the Google data, I turned to a source economists have barely used: the ParlaMint-UA corpus, which logs every word spoken in the Verkhovna Rada. I filtered two quiet stretches (Figure 4): the recovery years 2002 – 2007 and the pre-invasion window 2017 – 2022, and ran the same threshold test.

The result echoes the public pattern. Mentions of “inflation” hover near zero in single-digit months, climb as CPI approaches 9 – 10 %, jump at the first double- digit reading, and then ease back while prices keep rising. The fade-off is milder than in Google searches, meaning MPs keep the topic alive a little longer, but the turning point is almost identical.

Figure 4. Mentions of “inflation” in Verkhovna Rada speeches and estimated inflation thresholds (left: May 2002 – Sep 2007; right: Jan 2017 – Jan 2022)

One extra twist appears at the low-inflation end of the scale. The data show a few brief upticks in speeches when CPI is well below target. This happened in June-November of 2002 and May-September 2020 periods respectively. A plausible explanation is that MPs use these moments either to celebrate “price stability” or to signal support for cheaper credit (confirming that would require a deeper content analysis). What matters here is that those isolated blips lie outside the main pattern: for the bulk of observations parliamentary attention – like public attention – peaks around the first double-digit print and then gradually recedes.

Thinking About Why Focus Slips So Quickly

Why does attention jump so hard and slip away so fast? First comes the mental cliff: 9 % still sounds ordinary, 10 % sounds like trouble. Media logic reinforces that cliff – “Inflation hits double digits” writes itself, but follow-ups at 12 % or 13 % feel like yesterday’s story. At the same time other sirens crowd the feed – fresh headlines from the front line, sudden swings in the hryvnia, new COVID case counts, pension-indexation debates. With so many signals competing for notice, people treat the first two-digit print as a quick status check – “OK, prices are bad” – and move on. Stress avoidance plays a role too: tracking each extra percentage point means reliving the squeeze every month, so many simply look away. And things can be even more prosaic – many Ukrainians watch the dollar–hryvnia rate as a shortcut; if the exchange rate holds steady after the initial spike, they assume prices will settle as well, cooling further interest. Finally, there is a dose of trust: the National Bank has pulled inflation back before, so once the first shock is noted, most believe it will be handled. The blend of a sharp psychological marker, relentless competing news, simple currency heuristics and a preference for less stress helps explain why curiosity peaks at 10 % and then drains even while the cost of living keeps climbing.

Why It Matters:

Expectations

Inflation is not driven only by today’s costs – it is steered by what people expect tomorrow’s costs will be. When shop owners think prices will keep rising, they mark up a bit extra; workers who fear their hryvnias will buy less ask for larger raises. Many people in Ukraine also rush to swap their hryvnias for dollars or euros, weakening the exchange rate, increasing the cost of imports, and driving prices even higher. All these moves feed back into the very number everyone was worried about – the inflation rate itself. Economists call this the expectations channel, and it is powerful enough that central banks watch, model and try to guide it every month.

Attention is the on–off switch for that channel. When hardly anyone is following the data, expectations tend to hover around whatever long-term average feels “normal”. Once a headline shocks people into looking, they update – often in the direction of the latest print. In other words, a surge of curiosity can lift inflation expectations, which in turn nudges actual inflation higher.

We can see the mechanism in household surveys (Figure 5). From January 2024 to March 2025 inflation crossed the ten-percent line, and reported expectations jumped by roughly three percentage points – a spike that mirrors the attention burst. A few months later, even though actual inflation kept climbing, expectations drifted back toward earlier levels as public interest faded. The episode is a small but telling reminder: the more eyeballs on the CPI release, the greater the risk that expectations – and eventually prices – will follow it upward.

Figure 5. Households’ inflation expectations in Ukraine (Jan 2024 – Mar 2025)

More generally, figure 6 shows that when inflation is under 10%, households tend to expect higher than current inflation; and when inflation is past 10%, households tend to expect lower than current inflation. This suggests that 10 % either some natural long-term belief or the level that draws the most attention (higher attention to inflation results in expectations being closer to current values, as people are more aware of actual inflation during the poll).

Figure 6. Relationship between inflation and household “expectation error” (i.e. difference between household inflation expectations and actual inflation) for 01.2020-03.2025

Policy Windows

For the National Bank of Ukraine the takeaway is clear: because public attention flares only briefly, communication must hit while interest is still high. In practice that means speaking early – as soon as inflation drifts toward 8 % – with concise, jargon-free explanations of what is driving prices and how the Bank will respond. It also means using the brief peak in public interest that follows the 10 % headline to anchor expectations: outline a simple path back to single digits and back words with concrete, transparent actions. Once the headlines move on, detailed technical notes will matter mostly to analysts, so the heavy lifting has to happen during that narrow window when most Ukrainians are still watching the number. Handle that moment well, and the next inflation spike should look less like a panic and more like a problem already under control.

New Research

For other economists and policymakers the takeaway is straightforward: the human side of data matters. Knowing when people first notice a statistic, how they interpret it, and how quickly their attention fades can be as important as the figure itself. Mapping these patterns with Google search trends, news-media archives, or social-media comment streams lets us anticipate shifts in expectations, time policy messages for maximum impact, and turn momentary worry into lasting confidence when the next shock arrives.

References

- Bracha, A., and Tang, J. 2024. “Inflation Levels and (In)Attention.” The Review of Economic Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdae063.

- Buelens, C. 2024. “Googling ‘Inflation’: What Does Internet Search Behaviour Reveal about Household (In)Attention to Inflation and Monetary Policy?” SSRN Scholarly Paper 4751664. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4751664.

- Korenok, O., D. Munro, and J. Chen. 2023. “Inflation and Attention Thresholds.”

- The Review of Economics and Statistics. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01402.

- Sims, C. A. 2003. “Implications of Rational Inattention.” Journal of Monetary Economics 50 (3): 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(03)00029-1.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations