Oil. The Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered considerable debate on the reliance of European countries on this primary good – particularly the consequences for citizens and firms on their consumption and production.

While important, there is another type of oil that is relevant when considering how Ukraine (and its future) is inextricably linked with the daily functioning of local economies in the rest of Europe. By looking at this other type of oil – seed oil – we can appreciate the often overlooked, but highly impactful, ties that link Ukraine with a large and diverse set of local economies in the EU (and beyond). This link is through the geography of foreign direct investment (FDI) and global value chains (GVCs).

Ties that bind: how GVCS link Ukraine with EU local economies

A lesser-known fact to Russia’s dominance in petrochemicals is Ukraine’s dominance in seed oil. According to the Office of Economic Complexity (OEC), it is the country’s largest export, representing $5,320 million of exports in 2020 and transported for purchase in large quantities to Europe ($1,680 million), India ($1,440 million) and China ($971 million).

Ukraine is the global leader in seed oil – specifically, sunflower seed or safflower oil – and is responsible for 46% of global seed oil production. Russia is second largest, contributing another half of this again (23%). Considering seed oil as an intermediate product that feeds into the production of other intermediate or final products in multiple other countries through GVCs, three concerns for the European and global community become apparent: first, how the direct and indirect price changes from the war will affect firms; second, how this shock will oscillate across value chains; and finally, how different local regions rely on seed oil in different ways and thus the impacts will be felt spatially.

First, the direct consequences: seed oil prices jumped in 2022 and affected firms. But taking a GVC approach, it is clear this was not just firms that produce the crop or sell seed oil in its crude form that suffered. After seed oil is exported, it is often transformed into other products for further export into third countries, adding value in the process. Seed oil can be used in cosmetic products as a moisturiser or in the creation of food such as kettle chips or fries. Depending on their specialisms, different importing regions will use it in different ways.

For example, there are direct effects on suppliers in Europe such as major French fries producers in the Netherlands, where the region of Zeeland holds four such processing facilities. The direct effects also apply to global cosmetics clusters in Avignon in France and Cremona in Italy where seed oil is part of their moisturiser product mix. These regions are ‘downstream’ from Ukraine in the global value chain – they import the primary good, use it as an input, and export the transformed product again. Their access to necessary inputs, their cost of production, and ultimately their competitiveness are directly tied to the war, with wider economic and employment implications for the local economies in which they operate.

Further afield, there are also downstream consequences for producers of such goods relying on US suppliers, except here they are indirectly affected by price increases. Although these producers buy most of their seed oil from the US, the global interconnected nature of the market drove up prices everywhere. Last year, kettle chip suppliers in Pennsylvania were shutting down manufacturing lines due to price shocks permeating through GVCs from production difficulties in Poltavska oblast in Ukraine.

Some regions also benefit, either as direct competitors (for example, sunflower oil producers in Turkey, the Netherlands and Hungary; see Dun & Bradstreet 2022) or as indirect competitors, as manufacturers switch inputs from sunflower oil to other oil types. For example, rapeseed oil producers in Kent in the UK might benefit as suppliers switch production inputs due to the GVC shock.

This transformation and all the regions connected to this product highlight the importance of taking a GVC-aware approach when considering both the territorial consequences and impacts of the war – in particular, how the local, national and global decision makers may act in Ukraine’s interests for its reconstruction and recovery. Local economies in Europe have increasingly close ties with Ukraine through GVCs; timely reconstruction of these linkages is of paramount economic value for both Europe and Ukraine.

A look into the future: reshaping GVCS to the benefit of local economies

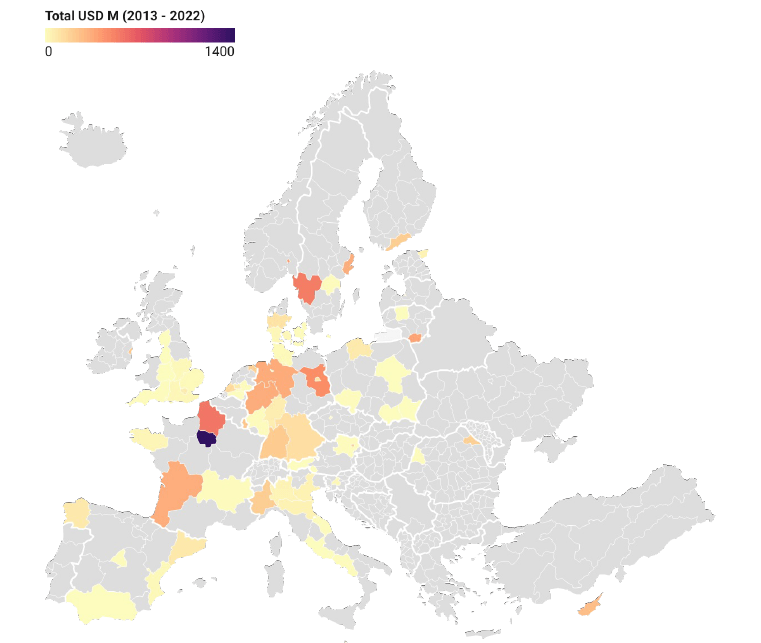

Rather than just accepting these consequences, our recent work outlines the role of public policy and the importance of FDI in harnessing GVCs (Crescenzi and Harman 2023). Looking specifically at FDI from the EU, the UK and Norway towards Ukraine (Figure 1), we consider changes in these investments and their implications for regional connectivity.

Figure 1 FDI from regions in the EU, The UK and Norway towards Ukraine (cumulative value of greenfield FDI flows, 2013- 2021

Notes: To align spatial scales, capital expenditure of Limassol, Cyrpus ($11.41 million) added to Nicosia, Cyprus ($255.9 million) and capital expenditure of Grevenmacher, Luxembourg ($11.23 million) and Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg ($1.62 million) added to Luxembourg, Luxembourg ($220.83 million) Source: Authors’ elaboration on BvD Cross-Border FDI data.

The largest manufacturing investment in Ukraine in the past ten years was Engie’s (a French multinational utility company) pre-feasibility activities for a solar power plant in Chernobyl in 2017 ($1,142 million). The second largest was Eskaro’s new coatings and paint manufacturing in Odessa ($536 million in 2013, with successive expansions). In the latter case, FDI explicitly ties the source region of investment (Gothenburg in the Västergötland region of Sweden) with Odessa oblast. What occurs in Odessa, the disruption and the difficulty, will subsequently have some consequences in Gothenburg – again as shocks transfer along the GVC.

Beyond seed oil (which accounts for the third largest FDI project in Ukraine by Cyprusbased Agroliga), neon is another relevant example of a product that plays a key role in multiple GVCs. Neon is a critical input to the extremely GVC-sensitive semi-conductor industry, and Ukraine produces 90% of semiconductor-grade neon used in the US. These semi-conductor (or micro-chip) GVCs were already under strain from Covid-19 pandemic following disruption in producing regions such as Fuijin, China. Further GVC restraints will likely reduce supply once more. But again, these impacts are felt regionally. Two companies accounting for approximately half of global high-purity neon supply are Cryoin in Odesa, Odeska oblast and Ingas in Mariupol, Donetska oblast, while the US’s largest semiconductor manufacturers are found in Texas and California. It is these regions which are most at risk if GVCs reshape.

Finally, it is worth considering Ukraine as a service hub. GVCs are not solely goods based, and while seed oil is the largest exported good, it is transport that is Ukraine’s largest exported service. This is also associated with FDI data. After Retail trade, the most frequent (service) investment in Ukraine is in Warehousing and support activities for transportation. Ukraine’s relative advantage in this stems from it sitting at a cross-roads between main trans-European corridors – both uniting Eastern and Western Europe as well as providing connectivity for the Baltic States to the Black Sea.

When breaking these investment flows down by business function, after Production ($3,130 million) and Electricity ($2,155 million), it is Logistics, Distribution and Transportation ($1,070 million) that received the highest FDI flows from Europe between 2013 and 2021. These are (still) relatively low value-added activities, but they play an important role in sustaining higher value-added creation in firms and regions in the sending economies along the GVC.

Turning to FDI originating in Ukraine’s regions towards the rest of Europe, FDI in postal and courier services emphasises Ukraine’s relative comparative advantage in this area. It is not just Kharvic and Chernobyl in Ukraine that benefit from inward FDI from the EU in GVC-sensitive industries; Galicia in Spain, Malopolskie in Poland, and Lisbon in Portugal benefit as destinations of FDI from Ukraine in GVCs. These are just three of the twelve regions that have received over $10 million greenfield FDI inflows from Ukraine since 2013.

GVCS, FDI and EU regional integration

FDI inflows and outflows – as well as the wider global, European and local value chains that they orchestrate – capture inter-regional connectivity. It is this connectivity that forms the initial backbone of future trade and investment flows in view of Ukraine’s accession to the EU. Ukraine’s centre of economic gravity – its international trade ties – has been moving West towards the EU and away from Russia since 2003 (Neffke et al. 2022). Yet, it is doing so at a slow rate, arguably because of generally low levels of FDI from the EU. For example, in 2019 employment in foreign firms was only 2% of total in Ukraine, contrasting with 7% and 9% in Poland and Romania, respectively. It has been argued that this still insufficient integration with the EU is a major contributing factor to Ukraine’s dismal economic performance compared to its peers since 1990 (Hausmann 2022).

If EU countries are serious about Ukraine’s candidate status or accelerated membership to the EU, then facilitating FDI and connected trade must be a key programme of work. To achieve this, de-oligarchisation, fighting corruption, liberalising foreign firms’ access to the domestic market, ensuring property rights, as well as reducing investment uncertainty and information asymmetries are critical. Some argue security guarantees should be part of this package to facilitate firms’ participation in value chains (Hausmann 2022). We would also propose important roles for horizontal and vertical public policy. This would mean deploying skills and infrastructure in a GVC-sensitive manner as well as connecting with GVCs through dedicated regional investment promotion agencies (Crescenzi et al. 2021). These agencies should work in a coordinated manner in Ukraine as a candidate country and in current EU member states. Pro-active vertical engagement with GVCs and FDI will facilitate the connection between the most appropriate inward or outward FDI and the most appropriate region to receive or provide it. This aids in managing investment in a context of significant information asymmetries and institutional failures.

These policies – where implemented in a well-coordinated manner – will play a key role in shaping future patterns of economic integration to the benefit of local economies, fostering cohesion and inclusive growth in all regions. For it is through FDI and GVCs that the connected nature of Europe’s regions to counterparts in Ukraine (and back again) is illuminated. Thus, the local economic importance of helping Ukraine now and in its recovery becomes clear. By helping and supporting Ukraine, local economies across Europe support themselves and their own future prosperity.

References

Crescenzi, R and O Harman (2023), Harnessing Global Value Chains for regional development: How to upgrade through regional policy, FDI and trade (1st ed.), Routledge.

Crescenzi, R, M Di Cataldo and M Giua (2021), “FDI inflows in Europe: Does investment promotion work?”, Journal of International Economics 132.

Dun & Bradstreet (2022), Russia-Ukraine Crisis: Implications for the global economy and businesses.

Hausmann, R (2022), “The Economic Case for Guaranteeing Ukraine’s Security”, Project Syndicate, 28 June.

Neffke, F, M Hartog and Y Li (2022), “The Economic Geography of the War in Ukraine”, Complexity Science Hub Vienna.

#helpUkraine_helptheWorld

This publication is a part of a collection of essays initiated by the National Bank of Ukraine. Famous economists, political scientists and historians, experts recognized in the world, volunteered to share their thoughts and arguments on why helping Ukraine is helping the world. The complete book of essays can be found via the link.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations