The macroeconomic news of the past few years has been filled with reports of alarming inflation records unseen for decades. Considering the backdrop of sluggish inflationary pressures following the 2008 global financial crisis and a fall in prices caused by the COVID-19 shock in 2020, the sudden inflation surge of 2021 and the price peak of 2022 seem pretty elusive.

The trajectory of inflation decline in 2023 also leaves a sense of ambiguity, spurring active debates on whether central banks have already reached the peak in their disinflationary efforts or whether sustaining disinflationary success will require an extended period of high interest rates, which, in light of the Great Recession or Secular Stagnation stereotypes (a period after the global financial crisis characterized by reduced inflationary pressure, declining nominal and neutral interest rates in many countries, and slowed productivity growth), seem highly uncomfortable.

How timely were central banks’ responses to the sustained deterioration in inflation forecasts after 2020? Do central banks’ reactions in developed countries differ from those in emerging market economies in the face of intense inflationary pressures? Was there enough resilience in inflation expectations for monetary authorities to confidently assume that supply shocks were temporary? Did supply shocks turn into a source of self-assurance, feeding incorrect assessments of the macroeconomic consequences of demand stimulus programs? Which monetary regimes are best suited to the challenges that shattered the global economy, and have changes in central banks’ preferences at the onset of inflation surge altered the sequence of price stability assurance regimes?

The answers to these questions have led to active academic discussions, often resulting in contrasting conclusions. Generalizing the most important aspects of central banks’ responses to the inflation shock in both developed countries and emerging markets (EM) is necessary in the context of domestic and international experiences, as is understanding why, almost for the first time, a global macroeconomic upheaval did not culminate in another round of currency and financial crises in poorer countries. In other words, have structural reforms in EM countries indeed borne fruit, and is external vulnerability now less of a driving factor in monetary decision-making? Can we assume that regulators are capable of overcoming the global inflation monster?

Inflation dynamics and central bank interest rate behavior

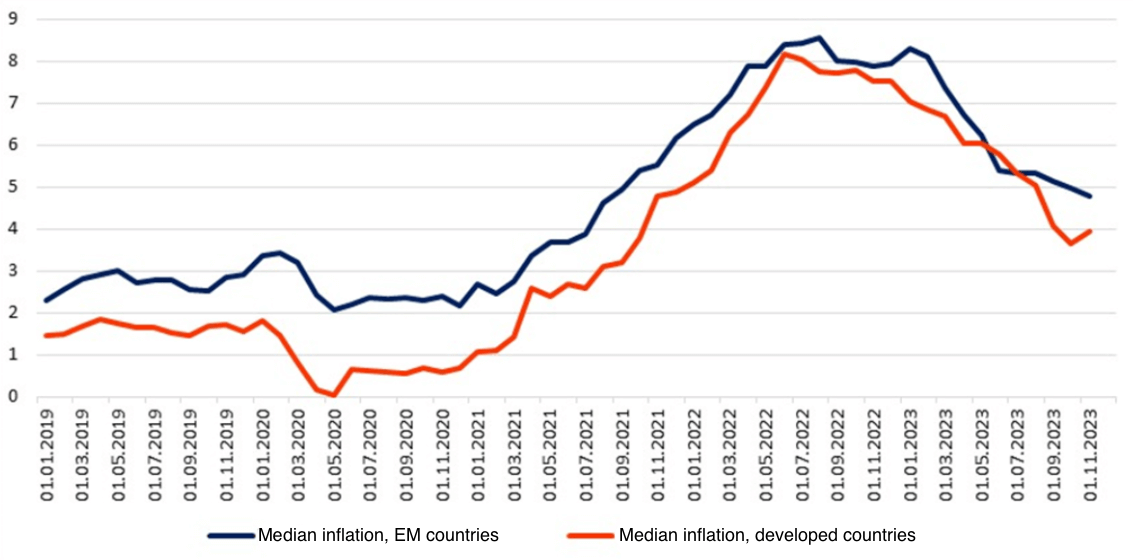

Even before the COVID-19 shock, there was a clear trend toward an increased correlation of inflation in developed countries and most EM nations. Global trade, value-added supply chains, capital market integration, etc. significantly influenced business cycles worldwide, making them more synchronized. Despite significant success in reducing inflation, emerging markets still tend to have slightly higher inflation levels compared to developed countries. During the price decline in response to social distancing measures in 2020, inflation rates in developed countries fell to around zero, while in emerging markets, they remained at around 2-3% (Figure 1). For example, in Ukraine, inflation in 2020 was 5%.

Figure 1. Inflation by country groups, 2019-2023

Source: Author’s calculations based on BIS data. Developed countries include the United States, the Eurozone, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Norway, New Zealand, Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden. Emerging market countries include Brazil, Colombia, Peru, Chile, Mexico, Israel, South Korea, South Africa, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Poland, Czechia, Romania, Hungary, Serbia, and Turkey. The choice of countries was influenced by several factors: most central banks in these countries are targeting inflation; central banks changed their key rates (Japan was excluded from the sample for this reason); Russia (the aggressor country) is deliberately not included in the analysis.

However, it turned out that anti-COVID restrictions, no matter how disruptive they were to economic activity, quickly triggered a suspended demand effect. Coupled with massive stimulative measures and a relatively healthy financial system (unlike the situation after the global financial crisis when entire economic sectors were deleveraging and financial companies were struggling with poor balance sheets), this led to a completely different dynamics in global inflation. Already in early 2021, it began to accelerate synchronously in both developed countries and emerging markets.

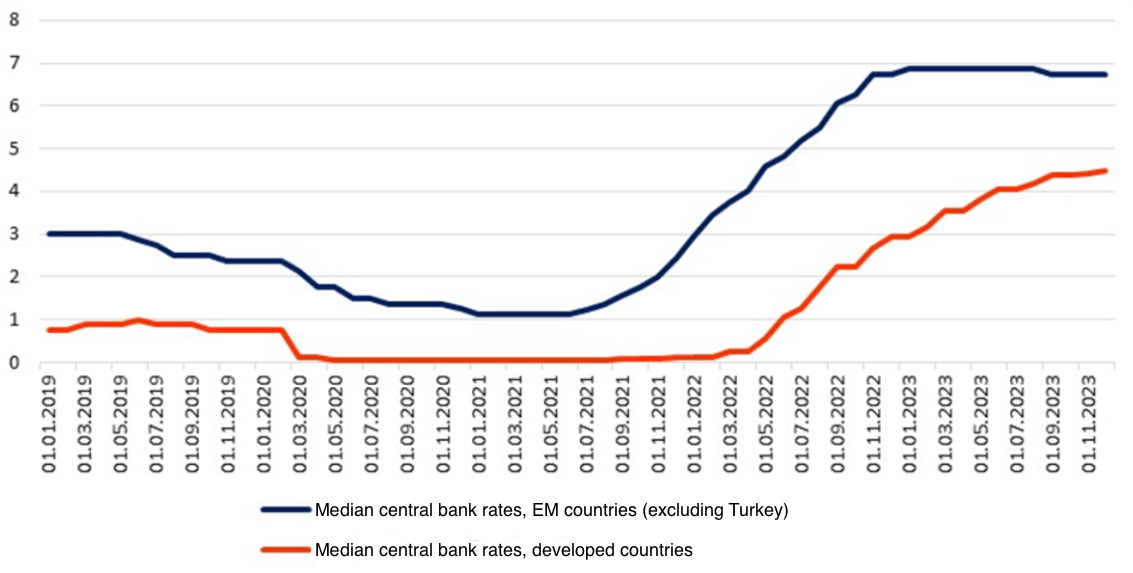

At the same time, as evident from Figure 1, inflation in developed countries reached levels close to that of middle-income countries at its peak in 2022. After this point, structural differences between these groups of countries became apparent. In developed countries, inflation gradually started to decline after sharp and delayed monetary policy decisions. However, in emerging markets, inflation remained stable for a longer period, followed by a more gradual disinflation after a sharp decline. This situation can be explained by greater inflation inertia in emerging market countries, increased sensitivity to commodity price pressures, and stronger pass-through effects. The nature of anchoring inflation expectations and trust in policy also played a significant role. These differences impacted the timing and strength of central bank reactions across country groups. Figures 2-3 show that central banks in EM countries started raising interest rates much faster and with less hesitation.

Figure 2. Nominal interest rates of central banks, 2019-2023

Source: Calculated and constructed based on BIS data

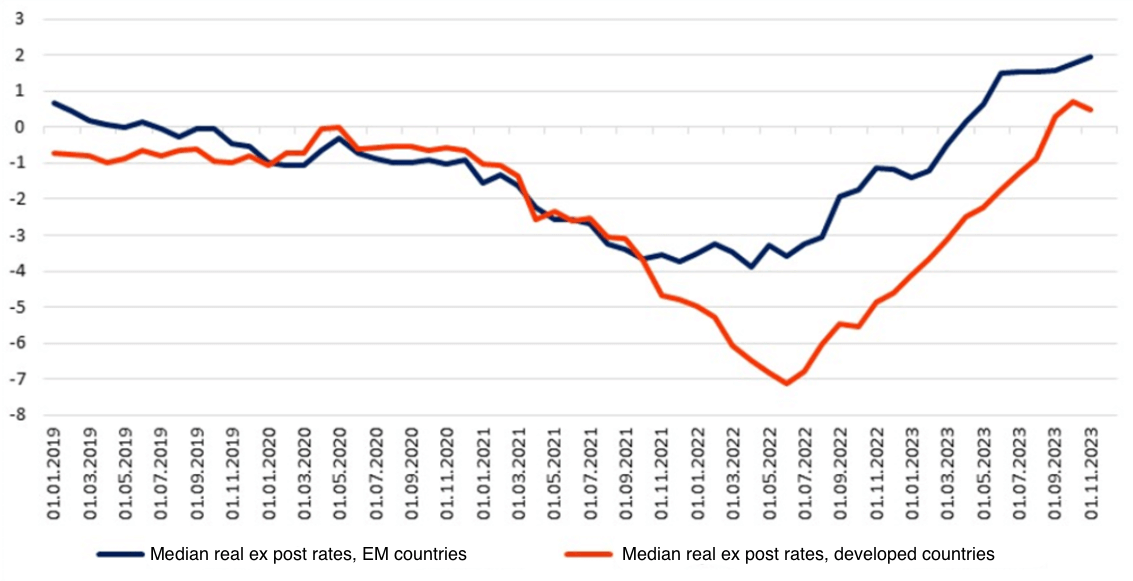

Figure 3. Real interest rates of central banks, 2019-2023

Source: Calculated and constructed based on BIS data

Thus, nominal interest rates were close to zero even before the COVID-19 shock. Real interest rates in developed countries had been in the red for a while. In EM countries, they were shifting towards zero (by the time of the COVID-19 shock, they had even fallen below the levels in developed countries). However, the situation changed when inflation rates began to rise. As evident from Figures 1-3, despite a relatively moderate and time-limited price shock, central banks of these country groups reacted very differently.

Central banks in EM countries started raising rates much earlier and held them at peak levels for longer than central banks in developed countries. They also started lowering rates slightly faster than in developed countries. Given the differences in inflation inertia, the duration of periods with rising real interest rates is likely to be longer in developed countries. In other words, structural differences became quite apparent. Price restraint and disinflation require a tougher policy stance in emerging market nations. In these countries, real interest rates were pushed into positive territory sooner and kept there longer than in developed countries to prevent economic crises. It seems that this “natural defensive reaction” has atrophied in developed countries.

Change in interest rates: Have external vulnerability factors become secondary?

External vulnerability had long been a macroeconomic Achilles’ heel for emerging market countries. Rapid and unpredictable shifts in capital flows, structural trade deficits, shallow financial markets, etc. together with institutional problems in macroeconomic policy led to profound currency and financial shocks. Strong pass-through and balance sheet effects made price and financial stability highly sensitive to exchange rate fluctuations. However, since 1990s these countries implemented deep structural reforms of institutional foundations of macroeconomic management, their financial systems deepened, and the accumulation of foreign reserves, along with the adoption of macroprudential practices, enhanced central banks’ ability to focus on inflation objectives.

Since most emerging market countries have gone through the interest rate hike cycle rather smoothly, the question is whether traditional external vulnerability issues motivated central banks to react cautiously to the inflation surge. Or did the focus on inflation targets play a greater role in regulators’ decisions to tighten monetary policy? The answer to this question will shed light on how well emerging market countries have structurally adapted to inherited external vulnerability issues and the extent to which concerns about deviations from the inflation target have dominated central banks’ reasoning. It is also crucial to determine whether the “macroeconomic shock – exchange rate – macro-financial destabilization” chain remains significant for monetary authorities or if they can afford to react to deviations of inflation from the target with greater exchange rate flexibility.

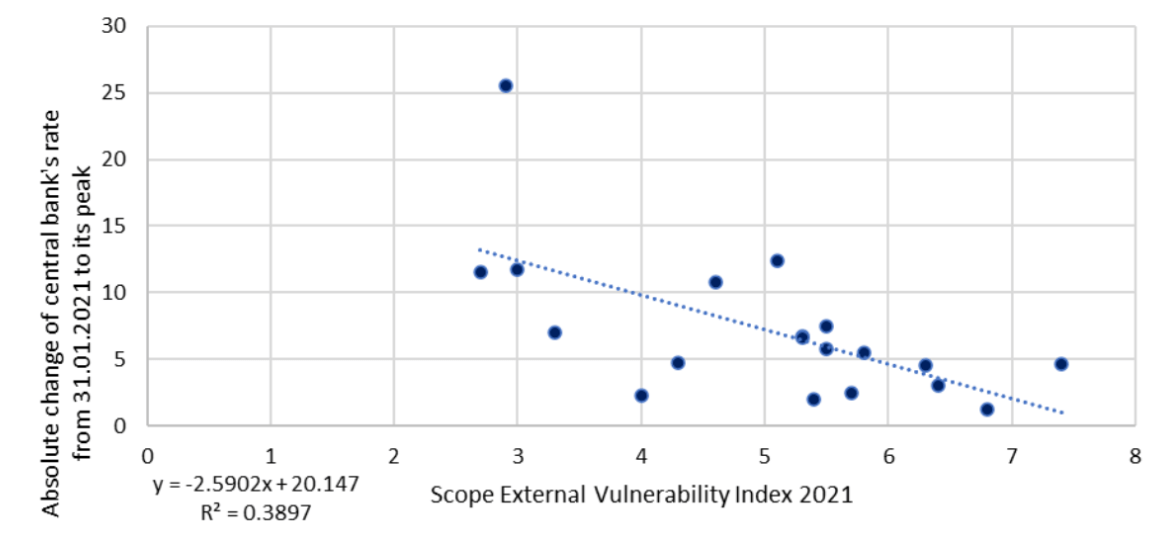

Figures 4-7 show that structural reforms in emerging market countries have indeed yielded some results. However, while external vulnerability is no longer a fatal factor, it still remains a compelling argument in favor of prudent tightening of monetary policy.

Figure 4. External vulnerability and central bank interest rate changes during the 2021-2023 inflation surge. Emerging market countries.

Source: Calculated and constructed based on BIS data

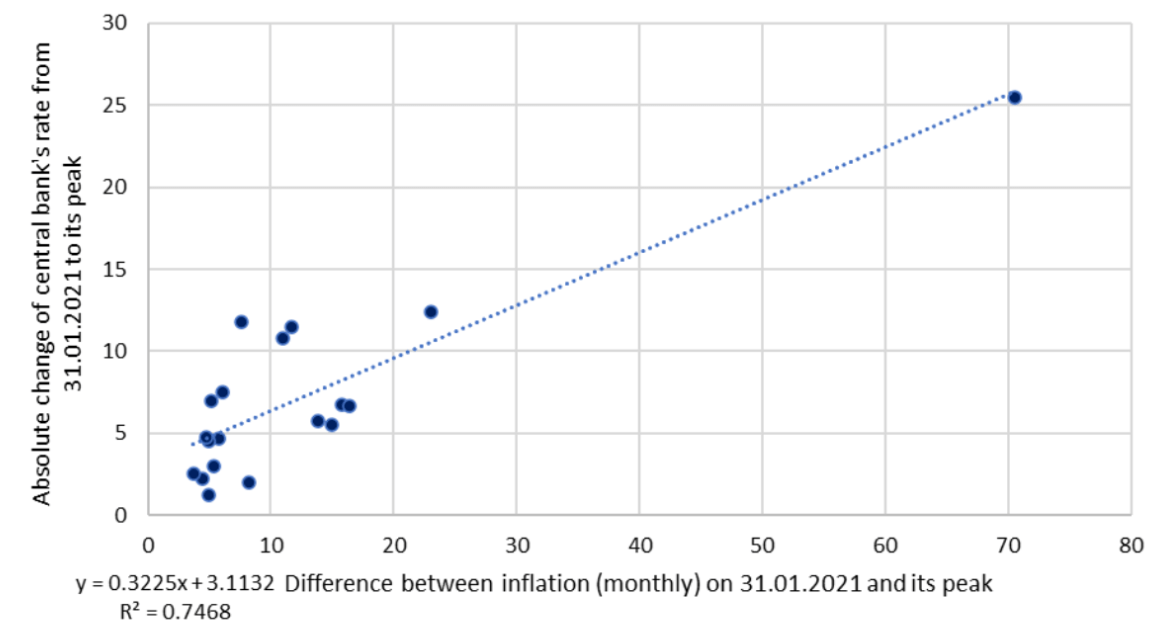

Figure 5. Inflation pressure and central bank interest rate changes during the 2021-2023 inflation surge. Emerging market countries

Source: Calculated and constructed based on BIS data

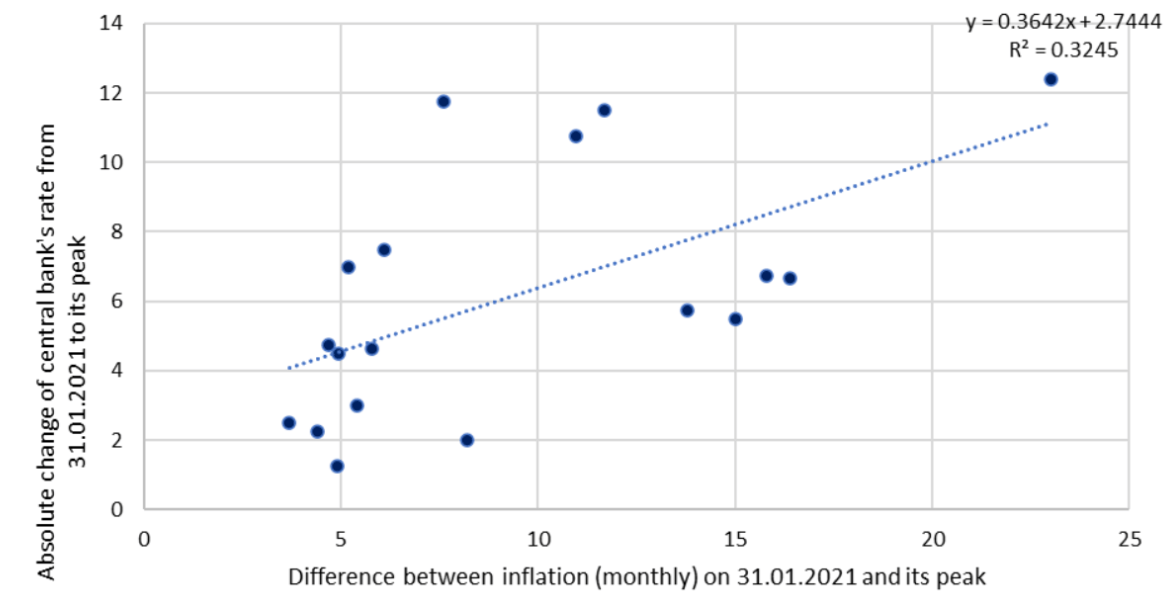

Figure 6. Inflation pressure and central bank interest rate changes during the 2021-2023 inflation surge. Emerging market countries, excluding Turkey

Source: Calculated and constructed based on BIS data

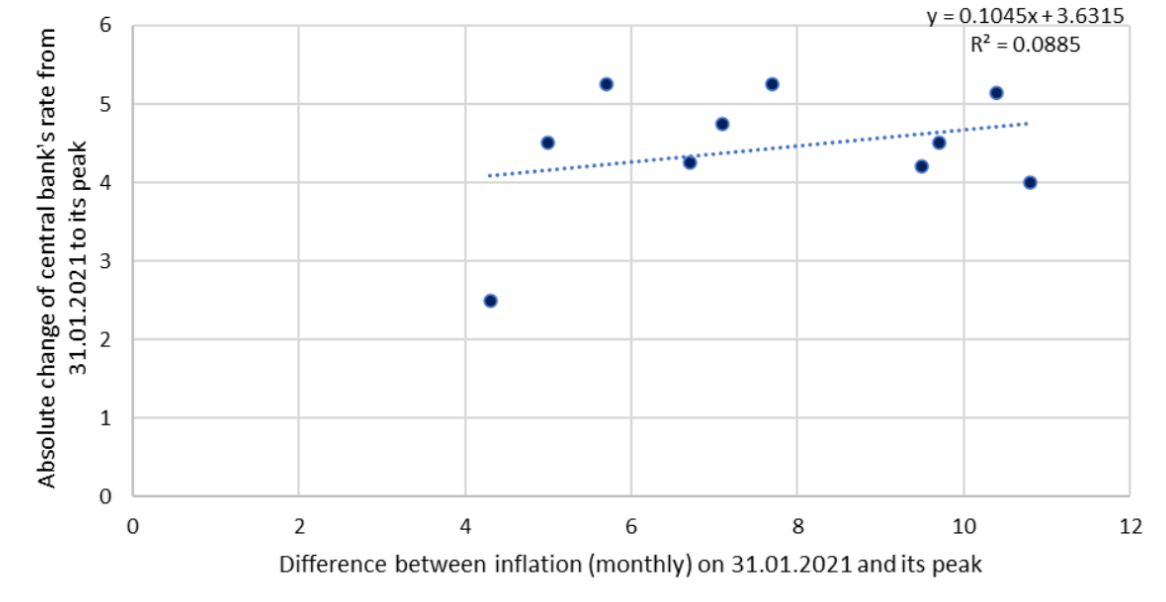

Figure 7. Inflation pressure and central bank interest rate changes during the 2021-2023 inflation surge. Developed countries

Source: Calculated and constructed based on BIS data

The factor of external vulnerability is represented using the Scope External Vulnerability Index 2021 (lower values indicate higher vulnerability). The inflation factor influencing monetary policy decisions is the difference between the peak inflation rate (year-on-year) for each country in the sample and the level of inflation as of January 31, 2021. The strength of the monetary response is assessed as the difference between the peak policy rate of the respective central bank on the relevant date and the rate on January 31, 2021.

Figures 4-7 allow for several generalizations. Firstly, external vulnerability remains a significant argument in favor of rate hikes in emerging market countries. The pass-through effects and devaluation risks due to losing confidence in maintaining price stability remain high. Secondly, the response of central banks in EM countries to the inflation surge is clear-cut. For the entire sample (Figure 5), the correlation is almost twice as high compared to the Scope Index (Figure 4). However, excluding Turkey from the sample reduces this correlation by half (Figure 6). Ultimately, the correlation between changes in central bank rates, inflation, and external vulnerability becomes equivalent. Thirdly, in the case of developed countries, the response of interest rates is weakly related to the magnitude of inflation shock. In other words, central banks in developed countries relied much more on trust to them, anchoring inflation expectations, and the ability of monetary communications to convince markets of the temporary nature of inflation acceleration. As seen in Figure 1, the consequences of this approach were more than straightforward – inflation acceleration and the need to maintain higher rates later and for longer.

However, the experience of the inflation surge from 2021 to 2023 is more complex than it may seem at first glance. Errors in interpreting the nature of the shock and overreliance on model-based inflation trajectory estimates were less pronounced where the external vulnerability was perceived as a safeguard against excessive macroeconomic expansion, particularly in EM countries. But this does not mean that price stability mandates were abandoned altogether. After all, the rate hikes were decisive even in developed countries. Despite easing price pressure, central banks are preserving higher rates to ensure the sustainability of disinflation. Premature policy loosening threatens unhealthy relapses and a strengthening of inflationary inertia.

The differences in monetary regimes are also a subject of discussion. Theoretically, the Fed’s strategy allows for more flexibility than the ECB’s. However, the Fed raised rates more aggressively, while the ECB attributed its slower rate hikes to the pronounced energy shock. Ultimately, rates were increased. Does this mean that more accommodative monetary strategies did not demonstrate apparent advantages? In 2021, as part of their communications, most central banks pushed the narrative of the supply shock being temporary rather than a need to create an inflation buffer. Therefore, it is challenging to determine to what extent the delayed response to the inflation shock resulted from more flexible strategies, such as average inflation targeting. Since monetary decisions were ultimately made in an environment of clear and significant price increases, it was likely more of a data interpretation error and an excessive reliance on anchoring inflation expectations than testing new approaches. Otherwise, we would have observed a quicker return to the monetary policy loosening cycle. In other words, a more flexible strategy might better align with achieving optimal outcomes under model conditions or during “normal” price volatility. In real-world conditions, especially in extraordinary circumstances, the boundary between different strategic approaches to ensuring price stability becomes vague. This can be considered a positive signal of readiness to withstand global price shocks.

Conclusions

While central banks have not entirely defeated global inflation, they appear to no longer be on the losing side in the battle against it. Will the experience of 2021-2023 serve as a deterrent against future inflation spikes? The answer is cautiously pessimistic. Uncertainty and rapidly changing structural conditions leave room for collective errors when fueled by common perceptions and initial conditions for interpreting cause-and-effect relationships. However, this is a unique case that is unlikely to occur frequently.

Overall, the most critical factor in successfully addressing inflationary shocks is the commitment to the mandate of price stability and the ability to consolidate the political, expert, and business community around this goal. Differences in monetary strategies will become more pronounced in an environment with less prominent shocks. The boundary between them will be rather unclear in extraordinary conditions, and the central bank’s readiness to demonstrate leadership in addressing macroeconomic disruptions will come to the forefront.

At the same time, the likelihood of a prudent response to the early signs of an inflationary shock is still influenced by external vulnerability, a sober assessment of anchoring inflation expectations, and the risks associated with reinforcing inflation inertia. Positive real interest rates have proven effective. Efforts to engineer disinflation while holding real interest rates in the negative territory hinge heavily on the accuracy of neutral interest rates estimates, making monetary policy highly reliant on model-based tools. In times of extraordinary macroeconomic events, experience and professional heuristics can serve as better guides for policymaking. This was demonstrated by central banks in emerging markets successfully preventing inflation from spilling over into macrofinancial instability.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations