The next month and a half will be crucial for Ukrainian medicine. The Verkhovna Rada will consider healthcare reform bills. If the acting minister Ulana Suprun succeeds in getting them passed by the Parliament, Ukraine will see changes in healthcare system already this year.

A thin middle-aged woman wearing spectacles and a black fleece jacket is sitting at a big table and listening impassively to respectable-looking, well-groomed people scolding her one after another. At last the woman is asked to speak, so as to respond to the accusations. She politely replies that she has not been planning to participate in a press conference; then she gets up and leaves.

You have just seen a meeting of the Verkhovna Rada Committee on Public Health. The woman in the sports jacket is the Acting Minister of Public Health Ulana Suprun. “Probably they are good people; but that is not a profession,” Oleh Musiy, MP and former public health minister, summarizes his opinion on Suprun’s team. His deputy Kostiantyn Nadutyi describes the MPH team as “a rabid flock of penguins.”

The antagonism between the ministry and the relevant committee has long reached its climax: each meeting turns into a farce. Both the MPs and the Ministry of Public Health claim that they support the same public health reform concept, aimed at putting an end to hospital bed funding, doctors’ miserly salaries, and corruption. However, since the autumn of 2014 only four would-be laws passed through the committee. (More than ten bills were either turned down by the committee or voted down by the Parliament.)

In spite of the “total war” in the realm of public health, Suprun has been implementing the reform faster compared to the previous public health ministers – Oleh Musiy and Alexander Kvitashvili. What is at stake is not anyone’s political ambitions but the length and quality of life of millions of Ukrainians: at present, our life expectancy is, on the average, ten years shorter than that of people living 1,500 km to the west of us. Does Ulana Suprun have a chance to “cure” Ukrainian medicine and go down in history as its first-ever reformer?

Soviet legacy

In December 2014 Arseniy Yatsenyuk was forming his government after the parliamentary election. At that time, former Georgian public health minister Alexander Kvitashvili, along with other experts, was finalizing work on a healthcare reform strategy for Ukraine. He happened to be the person that Yatsenyuk agreed to see in his Cabinet of Ministers as the Minister of Public Health. During the candidate’s interview President Petro Poroshenko, Volodymyr Groysman (the Parliament’s Chairman at that time), and Arseniy Yatsenyuk assailed him with questions about the concept of the reform and promised that the future minister would have free scope to act.

Kvitashvili looked set to succeed. Two weeks after his appointment he gave a press-conference with Kyiv’s mayor Vitaliy Klychko and told the audience about the pilot reform of the capital’s healthcare system. At the end of 2014, Kvitashvili described the stages of the future reform as follows: “Money should be allocated for a patient rather than a hospital bed; the system must be an open one; patients should be allowed to make choices (of the doctor and the medical institution – author’s note). In the first place, it is necessary to resolve the problem of tenders.” He promised that insurance medicine would be launched in 2015.

Kvitashvili, who continues to live in Kyiv after leaving the MPH, is still eager to tell a lot about the things that must be changed in Ukrainian medicine.

“The Ukrainian healthcare system operates according to a pattern proposed by Soviet academician Nikolai Semashko,” he says, “wherein the State Budget funds the medicine based on the number of hospital beds and square meters of infrastructure rather than the quantity and quality of services provided by doctors.” In such a system, money is spent inefficiently. Reporting on treated patients leaves a lot to be desired: it is unlikely that all beds are occupied; nor is it likely that the doctors have enough patients. But taxpayers have to fund them anyway.

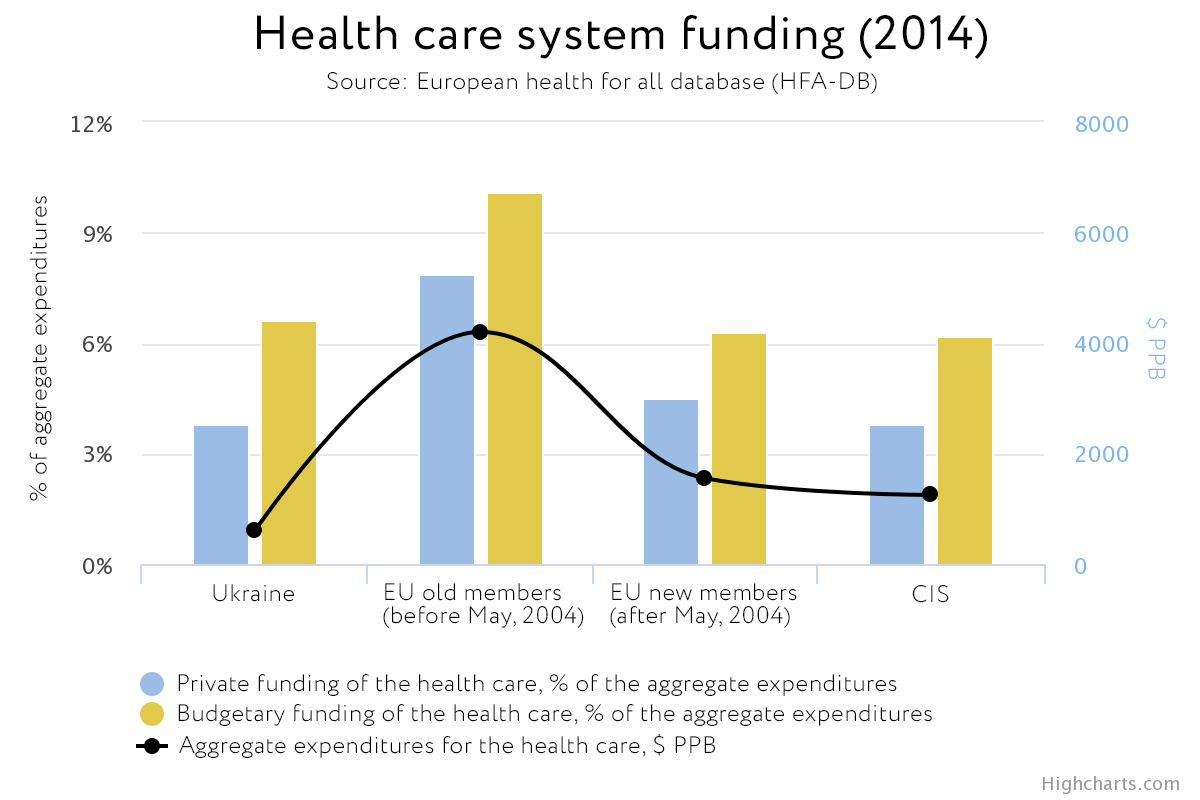

According to the World Bank, in 2005 Ukraine was in the world’s top 5 countries with the highest number of hospital beds: 8.7 per 1,000 citizens. Only Belarus, Russia and Japan were above Ukraine in the ranking. In 2013, Ukraine’s figure did not change. Yet the state healthcare budget is rather small, amounting to 3.4% of the GDP in 2017 (MPH data). In the new EU Member States, public medical spending averages 5% of the GDP; in the “Old Europe,” about 8%.

To reduce the number of beds in public hospitals or to start making patients pay means to violate the Constitution of Ukraine: Article 49 guarantees free medical care for the Ukrainians in municipal and public hospitals and prohibits the closing down of medical institutions. “This constitutional provision slows down all the reforms in medicine,” Kvitashvili says. However, he had a plan for overcoming these obstacles: Kvitashvili wanted to legislatively adopt a specific list of medical services that the Ukrainian State provides for free, to abolish hospital bed funding, and to pay doctors for services rendered to patients. One small thing was still missing: support from the lead committee of the Verkhovna Rada. And that was where the plan came to a standstill.

Recalling those times, Kvitashvili drops a few disparaging remarks about the head of the committee, MP Olha Bohomolets. At the end of December 2014, Kvitashvili presented his medical reform concept. Three weeks later, Bohomolets spoke of her own program “25 Steps to Happiness”.

With Musiy, things went wrong as well. Expert Kostiantyn Nadutyi, an aide to Musiy, says that Musiy had developed an own healthcare reform concept by the end of 2014. The expert believes that Kvitashvili borrowed many ideas from that document and simply left the committee on the sidelines of the reform effort. At any rate, it was practically impossible for Kvitashvili to pass his reform through the committee.

A year of war

For an insight into the milieu in which Kvitashvili was working, let us take a look into the past, into the autumn of 2014. At that time, it became clear that the MPH had failed to purchase crucial medications. As a result, Arseniy Yatsenyuk dismissed Musiy, the Minister of Public Health at that time. Shortly before that, Musiy explained the failure by claiming that his deputy Roman Saliutyn had been responsible for the delayed purchases and also by referring to the rising exchange rate and the complicated state procurement system.

The Center for Combating Corruption points to other causes. “(In 2014 – author’s note) the state system providing citizens with crucial medications was blocked by officials from the MPH and relevant departments, as a consequence of systemic political corruption,” the CCC said in its report on purchases in the public health sphere for 2014. That year, many hospitals received no drugs for patients suffering from tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis or cancer and no vaccines for children.

In a bid to get rid of corruption, Kvitashvili proposed that drugs be purchased through international organizations addressing healthcare problems worldwide. In February 2015, the Ministry of Public Health presented a bill on delegating state procurement of drugs to the World Health Organization and UNICEF. The bill was adopted, but the list of organizations was expanded; remarkably, in the end authorship of the law was attributed to Bohomolets and a few other MPs. Kvitashvili was again dissatisfied, but not about the authorship: the expanded list of organizations delayed the introduction of the new system of purchases, in view of the need to renegotiate arrangements with international actors and to update the MPH’s bylaws. It was only at the end of October 2015 that the MPH signed agreements with UNDP, UNICEF and Crown Agents.

In the spring of 2015, Kvitashvili’s war against the Ukrainian “political elite” became “hot,” following the initiation of an internal investigation against him: the reforms were progressing slowly; purchases of medications were not being made. One more allegation was voiced: allegedly, Kvitashvili intended to privatize the Ukrainian medicine. Bohomolets flushes when she recalls that situation: “If, in spite of the storm of accusations of corruption, we had not stopped such ‘reforms’, we would have trade centers instead of hospitals at present. I clearly said then: I won’t let Ukraine’s healthcare system be privatized!” She is of the opinion that in a country facing external aggression medicine cannot be based on a private ownership model.

In reality, the situation was a bit different. In July 2015, the Ministry of Public Health submitted a package of medical reform bills to the Parliament: Nos. 2309, 2310, and 2311. The main bill, No. 2309, addressed autonomization of medical institutions: transition from total funding of hospitals to payment for services provided by doctors; hospitals must be allowed to officially earn income. To that end, they must be granted enterprise status. This does not mean automatic privatization of hospitals; the initial version of the IPH bill did not provide for such an outcome.

Bohomolets interpreted that bill in a different way. “We blocked it (the package of bills – author’s note),” she says. “The committee drafted its own bill on the basis of that law (more precisely, package of bills – author’s note). Contrary to Kvitashvili’s reform model, a hospital has no right to sell its land or building.” The submission of an alternative bill is a tactical tool frequently used in the Parliament. “An alternative bill means an opportunity for or even enforcement of a dialogue in the Parliament,” Bohomolets explains. With Kvitashvili, however, no dialog ensued: the law on autonomization of medical institutions was not adopted at that point.

When in July 2015 Kvitashvili submitted his resignation, a draft resolution on his dismissal was already under consideration in the Verkhovna Rada. However, he was able to leave only when Yatsenyuk’s government resigned nine months later; before that, MPs enthusiastically criticized Kvitashvili in live talk shows and under the Parliament’s dome, but refused to relieve him of his duties.

Ulana, the Iron Lady

Ulana Suprun and her husband Mark came to Ukraine from the United States on the eve of the Revolution of Dignity. Before that, she had worked for many years as a rentgenologist; she had been vice-president of the New-York women’s clinic Medical Imaging of Manhattan. “In Ukraine, we were planning to translate Ukrainian books into English, to promote Ukrainian writers and culture. But the Maidan changed our plans,” says Ulana, who participated in the revolution together with her husband. Before becoming Acting Minister of Public Health in August 2016, she had been involved in the volunteer project “Protection of Patriots.” Luckily, she no longer had to earn her daily bread: after selling their share in the clinic and their house in New York, the Supruns have enough money.

Suprun, who has been the head of the MPH since August 2016, is much more efficient than Kvitashvili was. This spring the Parliament adopted bill No. 2309 on autonomization of medical institutions. To get this document enacted by the Rada, the MPH made concessions: omitted mandatory autonomization of hospitals and agreed to Olha Bohomolets as the author. Suprun says that this did not change the content of the reform.

Life is no bed of roses for Suprun in the Ministry or in the medical community. This is how she describes her ministerial routine: “In the MPH, documents either pass very slowly through the departments – and I receive them right before the deadline – or they are ‘lost’ altogether. About half of the MPH employees are constantly involved in light acts of sabotage.” This is nothing in comparison with conflicts with a number of well-known doctors. The meeting in the Committee on Public Health from which she walked out was attended by Borys Todurov, director of the Heart Institute. At the beginning of 2017, he declared that the Acting Minister was responsible for failure to purchase medications. Before that, war against the MPH was waged by Svitlana Donska, Ukraine’s Chief Oncohematologist. “The MPH always gets the blame: either for buying low-quality drugs and stents or for their shortage. But the same doctors drew up the lists of medications. And then it appears that they have a lot of medications at the warehouses,” Suprun says. To prevent similar accusations against the MPH in the future, the Acting Minister delegated all the purchases to international organizations until 2019, asked leading doctors (in particular representatives of private clinics getting nothing from the state) to compile lists of drugs to be purchased, and made public hospitals and polyclinics publish information on leftover medications.

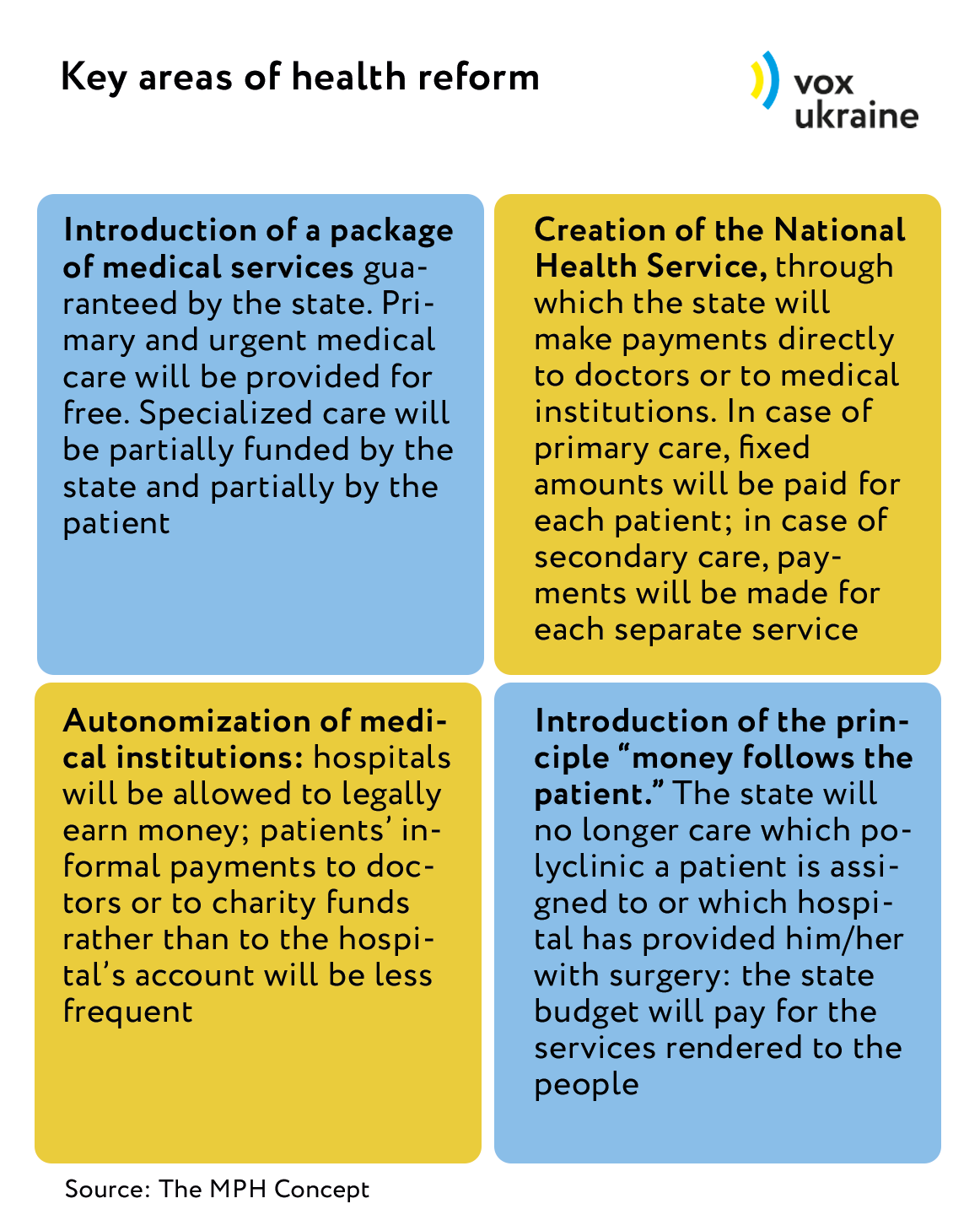

Suprun makes it no secret that she has been implementing Kvitashvili’s old proposals. However, she emphasizes that the MPH has taken into account the wishes of all stakeholders, including the VR Committee on Public Health. The reform has four key areas (source: The MPH Concept):

Usually, medical reforms encounter certain difficulties even in countries that are “more civilized” than Ukraine. “This is a highly public sphere and it relates to each one of us. Therefore, the MPH has to explain a lot about what we are doing and why,” says Deputy Minister of Public Health Pavlo Kovtonyuk. He keeps traveling around the country with Suprun, with her other deputies and RPR experts so as to tell the people about the future of medicine. However, this does not lead to a decrease in the number of questions asked by medics and patients alike. VoxUkraine interviewed six doctors, about a dozen experts and lots of patients and identified their main fears.

FEAR No. 1: There won’t be enough money for doctors in the budget

Doctors are apprehensive that hospitals will be closed down and they will be fired in the course of the reform. “Semashko invented the most humane healthcare system. He really cared for the people. But what are these guys planning? They will shut down the hospitals, including our in-patient facility. There will be so many unemployed persons,” says a nurse working in the Central District Polyclinic of Kyiv’s Desnyanskyi district. Her opinion is echoed by a doctor standing next to her. In reality, the MPH is not planning to economize on medical staff: doctors themselves will dispose of the money as a result of the autonomization of medical institutions. It will be up to the chief physician to make a decision to dismiss an employee; and up to the local authorities to close down or repurpose a hospital.

When doctors are asked how the Ukrainian medicine should be dealt with, their comments have a lot in common with the MPH plans. Recently, the Kyiv School of Economics conducted a World Bank funded survey of 25 chief physicians and 90 resident physicians from two regions of Ukraine. Most of the doctors are of the opinion that medical services must not be provided for free, except for emergency situations; therefore, co-payment by patients must be introduced. The doctors believe that if patients start paying them for services rendered and square meters of hospitals are no longer funded, then a significant amount of money will be brought out of the shadow economy. Moreover, the respondents think that the current amount of shadow payments is probably equal to the total public health subsidy from the state budget. Twenty-one chief physicians and heads of departments believe that the current budget could be used more effectively – in particular by giving hospitals greater financial freedom and the right to decide how they can make more money and how they can use their income.

But will there be enough money in the budget to pay for doctors’ services – for a start, at least in the primary aid sector? MPH representatives often say that family doctors will receive 210 UAH annually for each patient assigned to them. Bohomolets is not enthusiastic about that amount. “For the reform to be implemented, it must be based on realistic estimates. It is impossible to provide a patient with quality medical assistance and a skilled physician for an annual amount of 210 UAH,” she says, demanding that the cost of a service be calculated depending on its components. Oleksandra Betliy, expert from the Institute of Economic Studies and Political Consultations, also believes that lack of preliminary calculation-based estimates is a drawback of the medical reform. “At first, the concept was developed and the bills were drafted; it was only afterwards that the MPH started counting to determine what can be funded with the resources available. Actually, at present it is not quite clear what services will be covered by the state and what the co-payment percentage will be,” she says. It should be noted that the physicians will have to spend a lot: according to Oleksandr Zhiginas, adviser to Kovtonyuk, the available funds will be used not only on salaries to doctors but also to pay for municipal services or rent, for administrative staff services, basic drugs and taxes.

Kovtonyuk, the MPH official responsible for calculating the future cost of primary and secondary care services, says that 210 UAH per patient is not the final amount and that it will surely be changed more than once. “We take a look at the advanced hospitals, including private ones, at their real expenses. We will make assumptions. And then, based on those assumptions, we will start setting tariffs,” he explains. The deputy minister assumes that the tariff adjustment process will take up to three years. At any rate, in his words, the MPH would like the level of a family doctor’s monthly income to be as high as 10,000 UAH after taxes. Specialists like gastroenterologists and endocrinologists are expected to have an income of 20,000 – 25,000 UAH. It is still unclear how many patients they will have to receive to earn such an amount.

Anyway, an income of 10,000 – 20,000 UAH is not bad at all, considering that the average salary in the country is 6,752 UAH and that physicians earn 4,500 UAH, according to the State Statistics Committee.

The key question is: Will the new salaries be enough for doctors to support the reform? Opinions differ.

Viktoria Tymoshevska, the Renaissance Foundation Public Health Program director, is not sure that Ukrainian physicians will enthusiastically accept the salaries proposed by the MPH. “Physicians often earn even more due to informal payments from patients, pharmaceutical manufacturers and private laboratories,” she says.

“I am confident that many physicians will agree to a fair income, even if it is lower than their current one – when one can simply treat people under normal conditions instead of collecting cash from patients,” says Oleksiy Shershnev, director of the private clinic Ilaya. He believes that under the new system private clinics will readily compete with public ones for patients – and win the competition due to higher quality of services.

FEAR No. 2: Patients will pay for everything

If Ukrainian medicine is reformed, it will be somewhat similar to the British or Canadian healthcare systems – with many pro bono services, but also with the need for additional payment for a part of services from the patient’s pocket or through insurance. The MPH has not specified yet how large that part will be. Musiy is not content with that situation: “What if for example the state guarantee covers only 10% of the cost of appendectomy? And the operation costs e.g. 10,000 UAH? Will in that case the patients have to reimburse 9,000 UAH?” he asks. Then he adds that all will have to pay the same amounts for specialized assistance, regardless of the patient’s financial state. Either Musiy did not read the reform plan carefully or he resorted to manipulation. More often than not, appendectomy is a case of surgical emergency and so it is included in the guaranteed services package.

FEAR No. 3: There won’t be enough doctors for all patients

A healthcare system similar to that in Great Britain or Canada means long queues to doctors. Iryna Doroshenko, former citizen of Ukraine currently residing in Toronto, is unimpressed by Canadian medicine: it is hard to get appointments with family doctors and they are often reluctant to refer patients to specialists; the workload of the latter is even higher. Recently, however, Doroshenko visited one of Kyiv’s public hospitals, where she intended to undergo a medical examination. After that, her opinion about the Canadian medicine changed dramatically: “I’d rather wait for as long as it takes to see a Canadian doctor than once again face the hell of Ukrainian medicine.” Oleh Petrenko, deputy director general of the private clinic Isida, insists that queues to doctors are a ubiquitous phenomenon practically all over the world. Medicine is too expensive an item for any state to handle; and often there are simply not enough doctors to satisfy all the needs of the population.

Suprun does not know yet whether there will be enough family doctors for all patients: “In Ukraine, there are 20,000 such doctors. It is unclear at the moment whether that number will suffice: there are no reliable statistics on how many people visit doctors and how often they do so.” Kovtonyuk hopes that family doctors will help to collect statistics not only on the actual number of patients but also on their ailments. Even if such data is collected, however, it will merely be a huge pile of useless information, in view of the current state of work with data at the MPH. It is impossible to do without the National Health Service, which will be entrusted with analyzing it.

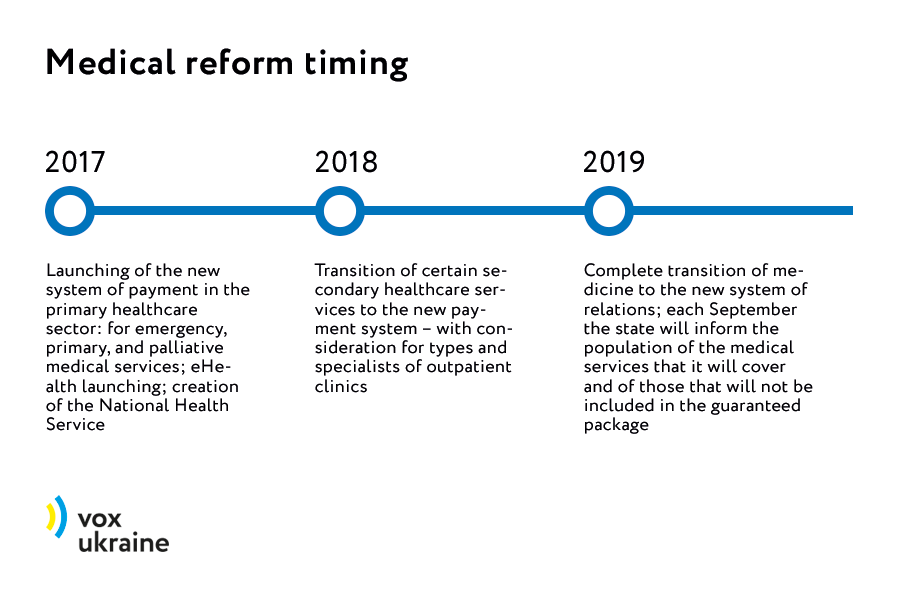

FEAR No. 4: It won’t be possible to choose a family doctor after July 1

According to Suprun, if someone fails to register for a family doctor before July 1, nothing will happen. It will be possible to choose or change a doctor later. The new system of payment for medical services will exist in parallel with the old one. Hospitals and polyclinics will continue to receive subsidies from the state and local budgets; and family medicine doctors who have concluded contracts with patients will receive payment for their services under the new scheme. The Ukrainian healthcare system will completely switch to payment in accordance with the principle “money follows the patient” from 2019.

What should be done in 2017: eHealth

At present, however, there is no way for patients or doctors to get registered: the eHealth system is unavailable. Its launching will be one of the stages in the reform, along with the initiation of the new type of primary healthcare funding and the National Health Service. These stages must be implemented this year.

The MPH has been working on each of these reform components; yet the process evolves slowly, accompanied by disparaging comments from quite a few critics. One of the former coordinators of the e-procurement division of the Ministry of Economics (ProZorro) Yuriy Buhai discussed eHealth with Ulana Suprun back in August 2016. It was more than half a year later, in April 2017, that the MPH presented a demo version of the future platform for registering contracts. More than 120 persons took part in the discussion of the initiative: Ukrainian developers of electronic medical systems, civil activists, doctors and experts. Andriy Hura, head of the developer company Medoblik, attended several meetings under the project. “It is unclear why the MPH brought together the entire market and had the whole congregation discussing the project,” he wonders.

Buhai comes up with his own logic: development by civil society of a product that is suitable for everyone is a better option than when developers impose their platform on the state or when the MPH starts a project and then abandons it after the next change of its leadership. While the project was being discussed, the companies developing medical systems fell out with Buhai and with the civil society organizations. In the end, however, all reached a consensus that the eHealth system will be developed by a design office headed by Buhai and financed by donors, besides the process will be under control of the anti-corruption and patients’ organizations. The state will own the data exchange standard, while any medical systems developer (such companies are quite numerous in Ukraine) will be able to develop an interface and get connected to the system. Currently, the formation of the eHealth project team is underway; practically all the executives have been selected already, but search for eight software developers was still going on at the beginning of May.

Developing the electronic platform is half the trouble. Without medical guidelines for doctors to follow, the Ukrainian medicine will remain at its current quality level. “Recently I had an ARVI – and the doctor prescribed hemorrhoidal suppositories for me. Is that normal?” Kyiv resident Tetyana Narizhna says with indignation.

What should be done in 2017: approval of guidelines

Doctors’ irresponsible attitude towards patients is frequently encountered in Ukraine. Suprun’s plan to address this problem is quite simple: she will make physicians follow medical guidelines telling them how to diagnose diseases and how to provide medical assistance in each particular case. However, in this connection the MPH is also widely criticized.

At the end of 2016 the MPH allowed Ukrainian doctors to use European, American and Canadian guidelines, evoking a barrage of criticism from experts, in particular those involved in developing Ukrainian guidelines – which are in fact based on Western ones. In the past few years, the State Expert Center under the MPH adapted 123 medical guidelines in accordance with Western ones. A similar amount of work still remains to be done.

Suprun does not understand why Ukraine should need its own guidelines if there are Western ones that can simply be translated into Ukrainian and then used. “People suffer from diseases in the same way everywhere,” she says. Critics agree with that, but add that, according to international standards, the guidelines must be adapted to the realities of local medicine and the public health budget.

According to RPR expert Oleksandr Yabchanka, the MPH wants to switch to Western guidelines because the old Ukrainian ones often required prescribing obsolete medications or drugs from specific pharmaceutical manufacturers. “If so, let the MPH point at least to one guideline mentioning controversial medications,” Lyshchyshyna says. In response, Suprun suggests that the doctors use both Western and Ukrainian guidelines. Cardiac surgeon Oleksandr Bablyak from Dobrobut, member of the European Association of Cardiac and Thoracic Surgeons, subscribes to her point of view. “I can see no problem with using Western medical guidelines,” he says.

For many years Ukraine has been living with no guidelines without any perceptible damage. But now they will be needed not just to protect Ukrainians against dishonest doctors. Payment to doctors through the NHS will depend on how strictly they follow the guidelines. Doctors prescribing unnecessary medications or examinations will simply get no payment from the NHS for their services. Suprun hopes that the NHS will start working in the autumn of 2017.

Same old song “about the most important thing”

No one will have to cross swords about Ukrainian medicine and there will no longer be any reasons for doing so if the Verkhovna Rada fails to adopt the package of bills needed to get the reform started. Lobbying for bill No. 2309 was successful, but it will be harder to succeed with the other ones. The main bill No. 6327 “On State Financial Guarantees for Providing Medical Services” describes Ukraine’s future medical system, mentioning a state-guaranteed package of medical services, the National Health Service, and deadlines for the reform. Three other documents are less important but also necessary: they provide for additional guarantees to ATO participants (this bill attempts to legalize international guidelines in Ukraine), amendments to the Budget Code concerning spending on primary healthcare, and amendments to the Law on Public Procurement.

“These bills have minimal probability to pass the Committee on Public Health in its current composition,” says Iryna Lytovchenko the co-founder of Tabletochki. However, the key committee considering the main bill No. 6327 is the one in charge of social policy rather than of public health; and the document was submitted on behalf of Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman. It is hard to believe that this was done for no special reason, although Suprun says so. She even consulted with the Verkhovna Rada Chairman Andriy Parubiy about the best timeline for submitting the bills to the Parliament, so as to ensure their safe passage. Parubiy recommended doing so after the May holidays.

In the opinion of Tymoshevska from the Renaissance Foundation, “if the package of laws is not approved, then our medicine will remain in its current awful state and everything will keep on sliding down.”

According to data from the State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, half a century ago the average life expectancy of Ukrainians was 71 years – just three years less compared to the Unites States at that time. Fifty years are gone; mankind has invented magnetic resonance tomography and taken up genetic engineering; pharmacology has undergone several evolutions. During that period, the average life expectancy in Europe and the United States has increased by 9 to 10 years. How about Ukraine? After the deep fall in the 1990s, the country has only recently returned to the average life expectancy recorded at the end of the 1960s. However, in the spring of 2017 deputies of the Verkhovna Rada of 8th convocation continue arguing vehemently whether the Soviet system should be preserved or the healthcare system prevalent throughout the civilized world should be given a chance here.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations